Tolling Time

Daniel Harrison

KEYWORDS: clock chimes, bells, time, carillon, Westminster Quarters, Rochester Quarters, Magdalen Chimes, Parisfal Chimes, Guildford Chimes

ABSTRACT: Five clock chimes (Parsifal, Guildford, Magdalen, Westminster, and Rochester) are analyzed to show how they communicate specific values about time. These chimes are shown to have two design elements, “distinctiveness” and “emergence,” that provide for particular kinds of temporal commentary.

Copyright © 2000 Society for Music Theory

[1] It is a commonplace that music can be made out of any variety of sounds, including those not originally intended for music-making. I am concerned here, however, with a different case: situations in which sounds with explicit pitch are neither meant nor heard primarily as music. Car horns, doorbells, buzzers, and other purely functional yet (proto-)musical sounds are—in this present culture, at least—not much more than acoustic signifiers, and arouse no one’s aesthetic appreciation save perhaps that of a composer inspired to use them. But I am concerned here with an even more specialized case, one in which acoustic signification is artistically grounded, where the sign feigns a pure functionality, the import of which apparently can be extracted casually by the observer (like a road sign), but which also—and even really—expresses a subtle bit of art. My object here is clock chimes.

[2] Are chimes amenable to musical analysis? This question would not have occurred to me until a short time ago, as I—like everyone else—heard mostly their functional message. To be sure, they have bits of tune, and one of the five chimes that I will discuss in detail here, the Westminster Quarters, actually forms quite a pleasant and memorable collection of tones, so much so that composers have used this collection as the motivic basis of an extended composition.(1) But I found myself in the position of having to write (compose? design?) a chime tune, and had therefore to consider whatever musical principles there happened to be in this apparently simple art. This article results from this unusual experience, and it is partly an analysis of existent clock chimes, partly a report on a model-compositional procedure for a new chime that resulted from this analysis, and partly a commentary on a music so regularly heard (like clockwork!) that it becomes part of the acoustic landscape of a particular place and eventually loses some of its quality as music.

[3] The Hopeman Memorial Carillon is installed at the top of Rush Rhees Library at the University of Rochester, 189 feet above the main campus quadrangle. Although it has fifty bells, played from a mechanical-action console inside the tower, only five are equipped with electric-action strikers activated by an electronic clock. Every quarter hour, the clock triggers the strikers in a melodic sequence, and the bells sound out over the campus. Depending on wind and ambient noise conditions, they can be heard up to half a mile from the tower. Several thousand people are within earshot of the clock chimes.(2)

[4] Since the original installation of bells in the library tower in 1930, the clock has chimed the Westminster Quarters, so named because of its adoption on the tower clock at Westminster Palace, where the British Houses of Parliament meet. (The lowest bell there, which tolls the hours and weighs thirteen and a half tons, is the famous “Big Ben.”) Having been reproduced in clocks both large and small all over the world, the Westminster Quarters is a well-known chime tune—perhaps the only tune people think of when the subject of clock chimes is broached. Its popularity certainly owes much to the attractive melodic sequence, but perhaps more to sentimental associations of British imperial pomp and circumstance, reinforced by the use of the Westminster Quarters by the BBC World Service for many years to preface the top-of-the-hour world news report on short-wave radio.

[5] As University Carilloneur, I am steward of the bells and the clock mechanism. Over the years, I had become curious about the practice of chiming quarter hours, and wondered to what extent this musical pronouncement of time—as opposed to the occasional passive glance at a watch or clock—might affect the life of the campus community. I had resolved in the summer of 1999 to see about changing the chime tune, partly to mark the sesquicentennial of the University of Rochester in 2000, but also partly to respect the wishes of the composer Sir John Stainer, who, in 1895, was quoted as remarking to a friend that “you will be doing a kindness in turning out the Westminster Chimes, of which everybody is heartily sick.”(3)

[6] I therefore looked at some existing chime tunes in order to learn the style, such as it was. I anticipated that the analytical work would be simple, quick, and of no lasting interest. I was surprised that it turned out differently.

[7] A useful feature of clock chimes is that each announcement of time within the hour have a unique melodic sequence. In this way, quarter past the hour, for example, can be distinguished by sound alone from half past, a useful advantage when one is not in the line of sight of a tower clock, or when (as is the case at the University of Rochester) there is no visible tower clock at all. I will call this rather elementary design feature of clock chimes “distinctiveness.” Another design feature, characteristic of English-style clock chimes, I will call “emergence.” Emergent chimes are marked by progressive lengthening of the melodic sequence during the course of the hour, with the shortest melodic sequence at fifteen past the hour (the “first quarter”) and the longest on the hour (followed by a tolling of the hour). Emergence can impart a definite temporal teleology, marking each hour as a culmination and not a beginning, as sixty minutes past a previous hour and not zero minutes of a new hour. This acoustical sensibility contrasts markedly with a visual one (reinforced by digital clocks) in which the hour is experienced as “:00.” Emergence thus is able to cloak the modular quality of time by depicting linear rather than circular motion within the hour, celebrating the arrival of the new hour both by completing the melodic sequence and by striking the lowest bell in the peal for the hour.

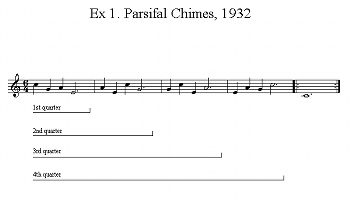

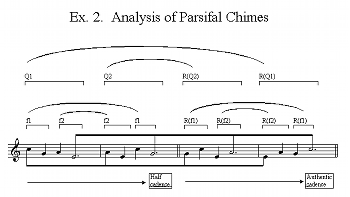

[8] Clock chimes can be composed to emphasize either distinctiveness or emergence. While one quality cannot eradicate the other, one can be so pronounced that the other becomes secondary unto accidental. A chime tune emphasizing emergence is shown in Example 1, the so-called Parsifal Chimes as they sound at Riverside Church in New York.(4) Using only four melody bells plus the hour strike, this chime adds a new four-note melodic pattern to each quarter hour. Distinctiveness thus results both from the number of bells struck at each quarter hour and from the unique four-note pattern that concludes each quarter-hour chime. While these unique patterns are a subset of the twenty-four distinct permutations of the four bells, the emergent structure can be modeled better by a different permutational design. Let each quarter phrase be composed of two ordered intervals of a perfect fourth, f1 = <C,G> and f2 = <A,E>, and let these two sets of ordered intervals themselves be ordered. Considering pitch succession alone, the chime pattern resolves thusly:

1st quarter: Q1 = <f1,f2>

2nd quarter: Q2 = <f2,f1> = R<f1,f2>

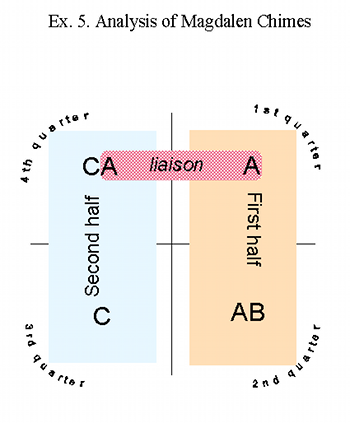

3rd quarter: R(Q2) = <R(f1),R(f2)>

4th quarter: R(Q1) = <R(f2),R(f1)>

[9] The sophisticated emergent effect that this structure creates is illustrated in Example 2. Two time spans are especially marked: the sixty-minute whole and two thirty-minute segments. The sixty-minute span is conveyed by a climax figure created by dotted-half notes that end each quarter-phrase. Counterpointing this rising line is its retrograde on the first quarter-note of each quarter-phrase. Upon completion of both lines at the fourth quarter, the hour is tolled on the lowest and heaviest bell in the instrument, a twenty-ton C2 that is the largest bell ever cast for a carillon. The hour strike thus “turns over” the modulus, transforming sixty-past into zero-hour, from which the registral ascent of the dotted-halves begins again. Within this sixty-minute span are two thirty-minute spans, the “outbound” and “inbound” half hours. The outbound is created by falling fourths, the last of which, f2, produces a half cadential effect at thirty past. The inbound, a retrograde of the outbound, is created by rising fourths and produces an authentic cadential effect at sixty past. The association of retrogression with inbound effects can be extended to the fifteen-minute spans as well, where the retrograde affects the order of the two perfect-fourth intervals. In this way, thirty-past is composed of an outbound quarter hour and an inbound quarter hour. The inbound half hour is similarly composed.

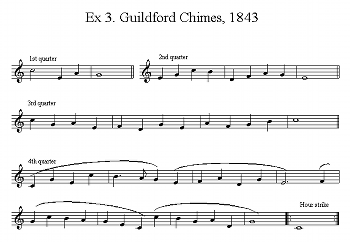

[10] In comparison to the Parsifal Chimes, the Guildford Chimes, shown in Example 3, emphasize distinctiveness, and what emerges over the course of the hour is not a single melodic entity, but rather something more abstract: a “compositional” sensibility that progressively displaces what might be called a “sound design” sensibility. The Parsifal Chimes has a limited number of available bells, and, as a result, it displays its design elements as the main feature of its art. In contrast, the Guildford Chimes has a peal of eight bells forming a major scale and thus offers opportunity for rudimentary tonal composition. Because of emergence, it takes advantage of this opportunity only gradually during the course of the hour. The first quarter, like that of the Parsifal Chimes, is a melodic sequence without much cohesion as a musical phrase. The second quarter presents a minimal phrase involving a tonic-dominant-tonic harmonic progression as well as polyphonic melody, thereby introducing an elementary tonal-compositional feature. A measure longer than the first, it concludes with an imperfect authentic cadence, appropriately signaling a conventionally important segment of the hour. The third quarter adds another measure, continues the polyphonic-melody technique, and presents in addition a definite melodic contour that strengthens the compositional sensibility at the expense of the design sensibility. Interestingly, the third quarter concludes with a perfect authentic cadence on the downbeat of the fourth measure, creating thereby a strong closing effect before the hour is up.

[11] The fourth quarter has a number of striking features. While the second and third quarters each added a single measure to the total, the fourth doubles the length of the third to cover eight measures. These eight measures contain four phrases that—save for a missing anacrusis in the first phrase—could set a typical English ballad text in an iambic common (86.86.) meter, a possibility shown by the phrasing marks in the example. The fourth quarter thus sounds like a “real” piece of music, something definitely composed rather than designed. Because of its exceptional nature, the fourth quarter stands apart from the previous three, and the curious closure effected in the third quarter is, in effect, the cadence of the overture before the main act commences on the hour. This idea of an hour “show,” incidentally, is realized spectacularly in a number of continental tower clocks, where cast metal puppets (“clock-jacks”) strike bells in full view of a presumably amused public. A very elaborate clock-jack show at the Rathaus in Munich has revolving multilevel stages on which dancers and jousting knights cavort.(5) (The inspiration for any number of Disneyland effects is obvious.) While no colorful clock-jacks emerge to ring the hour on the Guildford Chimes, a complete if rudimentary composition does. Perhaps the most unusual feature of the fourth quarter is its cadence, which is strongly on the dominant. The eight measures are thus tonally open and incomplete. It is the hour strike on the tonic that closes and completes the piece, conclusively resolving the dominant on which the fourth-quarter chime rested. In this way, the hour strike becomes part of the show—the denouement of it, actually—instead of being a event separate from the tonal structure of the chime.

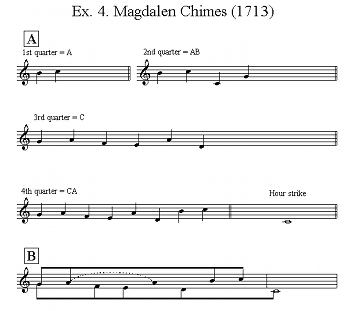

[12] The Parsifal and Guildford Chimes illustrate strong tendencies towards emergence and distinctiveness respectively. The Magdalen Chimes, shown in Example 4, has a more balanced relationship of the two features. (To ease the analytic discussion below, each quarter is denoted by thematic tokens.) Emergence is a straightforward affair, as two notes are added at each quarter hour. For the first two quarters, the chime seems to be unfolding a single tune in the manner of the Parsifal Chimes: A, A+B, and then possibly A+B+Y and A+B+Y+Z for the final two quarters, with Y and Z each being putative two-note motives. The third quarter, however, unexpectedly sounds a new melodic pattern, C, while still striking the expected six times. The fourth then takes C and, significantly, appends the two notes of A to it, completing the emergent total of eight.

[13] The teleological character of the Magdalen Chimes is thus quite different from that of either the Parsifal or the Guildford Chimes. Although in different ways, those two chimes “build” the hour and present the other quarters as supporting structures that prepare the ultimate goal. The Magdalen Chimes has a more modular character than the other two, and, while the fourth quarter is still the longest sequence, it seems less climactic than those of the other chimes. To be sure, it still presents something tonally coherent, with complementary linear motions converging on the tonic scale degree shown at B in Example 4. But this culminating effect is less powerful than that of the Parsifal Chimes because of the deployment of the motivic material.

[14] Example 5 maps the Magdalen Chimes onto an analog-clock grid marked in quarters, showing the hour to be divided into two distinct half hours. These time spans are different from the inbound/outbound half hours of the Parsifal Chimes, which convey a kind of pendular oscillation. The Magdalen half hours, as Example 5 suggests, are experienced as two different entities because motive C—the irruptive event of the third quarter—dramatically separates the first from the second half. Both half hours are further marked by other features. The second and fourth quarters (the concluding segments of each half hour) use the lowest bell in the peal to create cadential effects appropriate to the time spans in question. In the second quarter, this tonic precedes a dominant one, producing a half-cadential effect, whereas in the fourth quarter, the low bell reinforces the authentic-cadential effect of the concluding motive A of the chime. Reinforcing these tonal signals of conclusion is the use of compound motivic figures at the second and fourth quarters: AB at the second and CA for the fourth.

[15] To some extent, motive A cuts against the half-hour division. By recapitulating A from the first half hour, the fourth quarter creates a liaison between the ending of the second half and the beginning of a new first half, so that the hour event is experienced less as a culmination and more as an anticipation of the following hour segment. In other words, the motivic combination CA in the fourth quarter defines the hour as the median between the third quarter of the present hour (C) and the first quarter of the hour to come (A). In this way, the first quarter can be heard as an echo of the previous hour; it looks backwards rather than forwards.

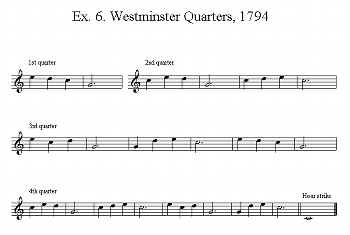

[16] Like the Magdalen Chimes, the more famous Westminster Quarters (Example 6) balances distinctiveness and emergence. The fame of these chimes is such that its origins are well documented. The composer William Crotch (1775–1847), while a student at Cambridge in 1794, was asked to write a chime tune for a new clock at the university. He took the fifth and sixth measures of Handel’s “I know that my Redeemer liveth” from Messiah as his inspiration, and—considering them somewhat as a designer of a change-ringing method—produced four sets of permutations on the four bells (G,C,D,E).(6) Each permutation is shown below as ordered sets of quarter-phrases, which are defined by the rhythmic signature of the Westminster Quarters: three quarter notes followed by a dotted half. Note that the second quarter-phrase of the second quarter is a “malformed” permutation due to the absence of the G bell:

First quarter: <E,D,C,G>

Second quarter: <C,E,D,G> <C,D,E,C>

Third quarter: <E,C,D,G> <G,D,E,C> <E,D,C,G>

Fourth quarter: <C,E,D,G> <C,D,E,C> <E,C,D,G> <G,D,E,C>

The relationship between the permutational and temporal structures can best be illustrated by recourse to the following abbreviations:

Q1 = <E,D,C,G>

Q2 = <C,E,D,G>

Q3 = <E,C,D,G>

Q4 = <G,D,E,C>

MQ = <C,D,E,C>

First quarter: Q1

Second quarter: Q2 MQ

Third quarter: Q3 Q4 Q1

Fourth quarter: Q2 MQ Q3 Q4

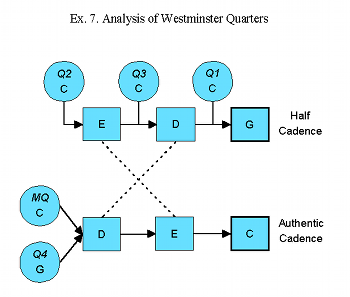

[17] As was the case with the previous chimes, cadential effects are coordinated with quarter-hour segments. In the Westminster Quarters, however, these are prominent and may even be said to be paramount. But other forces are at work here as well, and these endow this chime with different levels of structural cohesion. Like the Parsifal chimes, the Westminster Quarters builds the hour from quarter phrases, but there is no rigid assignment of a particular phrase to a particular quarter hour in this case. All odd quarters (i.e., the first and third) use quarter-phrases with half-cadential effects (Q1, Q2, Q3), while even quarters use phrases with authentic effects (Q4, MQ). The odd quarters thus conclude with a G, and the even with a C. This observation suggests that Crotch’s permutational design has at least some partial ordering constraints. These are explored further in Example 7, which adopts a “node & arrow” system from David Lewin to show a left-to-right ordering of events.(7) Those events in squares have fixed precedence, while those in circles are movable, appearing in the sequence at the indicated quarter. Thus, in the half-cadential quarters, E is always before D, which is always before G; C—to use the parlance of change ringing—“hunts” in the order, moving about the other, fixed bells. Further, it hunts in a consistent way. The three half-cadential quarter-phrases are heard six times during the course of the hour, proceeding from Q1 at the first quarter, through Q2 at the second, to Q3 and back to Q1 at the third, and finally to Q2 and Q3 at the fourth.

[18] The authentic-cadential phrases, as Example 7 shows, have a different ordering design. To be sure, C no longer hunts but is fixed as the cadential end. Yet D and E exchange precedence as well, as the dashed lines indicate. It is this change that gives the Westminster Quarters a pleasing balance and symmetry more subtle than that created by the alternation of cadential effects. These effects are obvious; the change of (E,D) precedence is less so. (Yet, as an experiment, create for yourself an authentic-cadence permutation in which E precedes D and substitute it for either MQ or Q4. The effect is surprisingly dramatic.) Just as the six half-cadential opportunities are parceled out to three different quarter-phrases, the four authentic-cadential opportunities are sounded by two different quarter-phrases, MQ and Q4, that alternate consistently—MQ being heard first and then Q4, followed by MQ and the final Q4.

[19] The cumulative effect of the design is multilayered. The consistent rotation of quarter-phrases over the course of the hour provides a subtle sense of modularity to the hour while not interfering with the teleology of emergence. Moreover, this rotation allows the astute listener to tell what time it is by hearing the first quarter-phrase alone, the one exception being the fourth quarter. At a middle and more easily-heard level, the alternation of precedence for E and D creates a pleasing balance and undulation to the unfolding chime tune. And at the surface, the cadential effects create half-hour units from rudimentary quarter-hour antecedent & consequent constructions.

[20] The Westminster Quarters seems to comment on the passing of quarter hours in the following way: A short quarter-phrase ending half-cadentially signifies the first quarter, which seems an obvious incomplete section of time. The second quarter, which ends authentically, seems more complete yet not whole. The obvious incompleteness of the first quarter (marked by Q1) is avoided by the use of a “new” quarter-phrase Q2. But the use of the “malformed” permutation, MQ, lessens the cadential strength. The second quarter is thus not heard as the first quarter plus another, but rather as an original half. For the third quarter, a completely new representation of the first half hour (Q3+Q4 instead of Q2+MQ) is followed by the original marker of incomplete quarter time, Q1. In a literal sense, the third quarter does not “contain” the previous two but is a new entity that, by concluding with Q1, recapitulates that quarter’s message of incompleteness. This situation becomes clearer at the fourth quarter, where two equal segments make up a satisfying whole: an outbound “malformed” 30-minute segment (Q2+MQ) and inbound “well-formed” 30-minute segment (Q3+Q4), previously heard in the third quarter satisfactorily to “seal” the outbound half. In this light, 45 past does not resolve to 30+15, but rather to 60-15. The third quarter thus looks forward to and anticipates the hour to come.

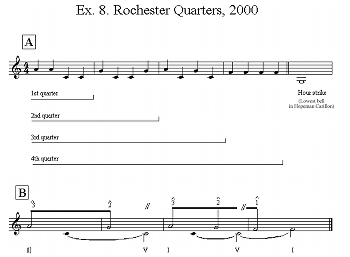

[21] In composing a new chime for the Hopeman Carillon, a number of novel ideas occurred to me, such as designing “third-hour” chimes that would sound every twenty minutes, or (and this was admittedly impish) having chimes sound, say, every eighteen minutes on a six-hour modulus. But I was restrained by a sympathetic consideration for the “user community”—for the people who might possibly rely on the clock chimes to regulate their lunch hour, to gauge their arrival time at class, or simply to order their day in a traditional quarter-hour rhythm. This was not a matter of artistic composition, but of maintaining the integrity of a publically-traded signifier. An eighteen-minute interval, for example, would no doubt force people always to look at their watch to figure out what time it was, which could be a continual annoyance. Moreover, it would defeat the original mission of the clock chimes to tell time using sound alone. While entertaining these notions, I was also reminded of the reception that Richard Serra’s “Tilted Arc” received when installed at the Federal Building plaza in New York; what had been a bland but functional space for unfettered human movement become blocked by a 120-foot length of worked steel, twelve feet high. An outcry ensued and, after a highly publicized lawsuit, the sculpture was removed.(8) A similar point for modernist aesthetics I did not care to make. Nor, in the end, did I want to trouble the engineers at the Verdin Company, the manufacturers of the clock chime mechanism, with my whimsy. So I resolved to maintain the quarter-hour chiming. As it was, a new logic chip would have to be manufactured for the quartz clock that triggers the strikers, and this would strain my limited budget. To avoid the expense of additional strikers, which would have created opportunities for a more expansive, Guildford-style composition, I decided to use the same bells as those used for the Westminster Quarters.

[22] The first problem was thus composing a chime tune that sounded manifestly different from the Westminster Quarters, whose bells and timing it would nonetheless share. Seeing little opportunity for emphasizing distinctiveness under these conditions, I opted for an emergent design (Example 8a) like that of the Parsifal Chimes.(9) The main innovation of the Rochester Quarters is its phrase structure. Whereas both the Westminster Quarters and Parsifal Chimes have distinct quarter-phrases, emphasizing the quarter hour as the unit of measure, the Rochester Quarters presents a new segment of a single if miniature tonal structure at each quarter hour. This structure is best explained in Schenkerian terms, as seen in Example 8b. The chime marks each quarter-hour segment with a report of progress towards completion of the fundamental 3-line. A major interruption occurs at the second quarter, which effectively couples the half hour with an important structural event. At the third quarter, the Kopfton is regained and the line begins a descent in double time, clearly aiming towards arrival on at the downbeat of measure 4 (=fourth quarter). The interruption at the third quarter (marked by breaking the beam) disrupts this motion dramatically—marking the third quarter as the point of greatest tonal and temporal tension within the hour. At the fourth quarter, this interruption disappears as progresses to without pause.

[23] The chime at the first quarter points out a defect in the fundamental structure: there is no apparent tonic support for the Kopfton . Given the length of the piece, and given that there is only one bell sounding , there was no way to put that scale degree in service of both the upper voice and the bass. To have put in the first-quarter chime would have suggested a downward bass arpeggiation to , or would have created some other registral confusion as to what was upper voice and what was bass. Despite this issue, the absence of a support for the Kopfton actually enhances the effect of the chime by making the first quarter a decidedly incomplete structure. As the hour passes and the tune unfolds, the attainment of and of an attendant structural “repair” becomes apparent. That is, the final , while appearing within the upper voice-leading, also creates the heretofore missing bass line; a single note (C as ) cannot be a line, but two (CF as -) can. Although the bass arpeggiation is truncated, it occurs nonetheless as part of the last event in the structure. With some imagination, it is not hard to hear the first two s as upper-voice pitches, and the last two as bass voice, as Example 8B graphs.

[24] The Rochester Quarters debuted on January 31, 2000, the sesquicentennial anniversary of the signing of the university charter. I did some advance publicity for the change, so that the community was somewhat prepared, but it was not extensive. Reaction was largely positive, which has been gratifying because, in truth, what I composed is not as deeply interesting as the Westminster Quarters from the theoretical perspective; given four bells, a lick from Handel, and the reflected glory from most famous and prestigious bell tower in Western culture, it is hard to improve upon the Westminster Quarters. The student newspaper did find cause for complaint; I had tampered with one of the few venerable traditions the campus had, and the new chime sounded like “

[25] All reactions, whether positive or negative, seemed to comment not so much on the chime tune itself, but rather on a renewed appreciation for being called to note the passing of time, and to note it with some pleasure. Buzzers, electronic beeps, and other assorted chirps also mark time, but crudely and without intelligence. Moreover, many are meant as private signals (e.g., the watch alarm), which makes their public impact one of inadvertent rudeness. The clock chime, in contrast, is a courteous public service. It asks to be appreciated rather than merely noted. The examples analyzed here also communicate something about the passage of time, and not just about a particular time point. They all use musical means to comment about what time it is or what part of the hour it is, and the consistent repetition of these comments throughout the day encourages one to transfer characteristics of a particular chime pattern to a particular quarter-hour segment. Fifteen past sounds different—and therefore feels different when heard—from forty-five past. Gradually, like all things that repeat mechanically for an indefinite term, these feelings aroused by the clock chime, as well as the attention paid to the chimes themselves, blend into the background of daily routine. The chimes will be heard instead of listened to, and the time points they mark will sound dull instead of sharp. But there will still be yet a unique and intrinsically musical sense of time in the place wherein they sound, a sense its denizens will share for as long as the bells continue to toll their particular story.

Daniel Harrison

University of Rochester

Department of Music

205 Todd

Rochester, New York 14627-0052

hrsn@mail.rochester.edu

Footnotes

1. See, for example, Louis Vierne, “Carillon de Westminster,” from Pieces de Fantaisie for organ.

Return to text

2. For more information about the instrument, consult its website: http://www.cc.rochester.edu/College/MUR/carillon.html.

Return to text

3. Quoted in W. W. Starmer, “Chimes,” Proceedings of the Musical Association 34th session, (1907–8): 8.

Return to text

4. The melodic sequence from Parsifal upon which the chime is based is found at the end of the “Good Friday” scene in the third act. According to Percival Price (Bells and Man [Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1983], 182), this sequence “

Return to text

5. For a useful web site (with bibliography) concerning clock jacks although not dealing with those in tower clocks, consult: http://www.database.com/~lemur/dm-clock-jacks.html.

Return to text

6. See Starmer, “Chimes,” page 9. Starmer quotes a “Dr. Raven,” to whom was written a letter by a “Mr. Amps,” who apparently knew the origination story of the chime. Dr. Raven notes that Crotch’s permutations show evidence of a systematic order “

Return to text

7. See David Lewin, Generalized Musical Intervals and

Transformations (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987), 134–5, 209 ff. For a more concise treatment, see David Lewin, “On Partial Ordering,” Perspectives of New Music 14–15 (1976): 252–59.

Return to text

8. For more information about “Tilted Arc,” including bibliography, consult: http://www.arts.arizona.edu/are476/files/tilted_arc.htm.

Return to text

9. The hour strike on G is correct, despite the obvious clash with the remainder of the chime. This G is the lowest bell in the Hopeman Carillon, and it also struck the hours when the Westminster Quarters (also set in F major) chimed from that instrument. Many chimes lack a bell large enough to act as a suboctave tonic for hour strikes, so hour strikes often occur on whatever the largest bell is regardless of key.

Return to text

10. University of Rochester Campus Times, Februrary 3, 2000.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2000 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason and Tahirih Motazedian, Editorial Assistants