Review of Timothy L. Jackson and Veijo Murtomäki, eds., Sibelius Studies. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001). 397 pages.

Olli Väisälä

Copyright © 2002 Society for Music Theory

The Janus-faced Sibelius

[1] As discussed in the Preface of Sibelius Studies, the reception of Jean Sibelius’s music has been marked by a curious dichotomy. By and large, musicians, the musical public (with certain geographical limitations), and the recording industry have enthusiastically promoted its cause, while “academics outside Finland have taken Sibelius seriously only recently” (xv). The most famous or infamous epitome of the “academical” scorn for Sibelius, Theodor Adorno’s “Glosse über Sibelius,” is quoted once again in the Preface. And certainly, in view of his formidable intellectual influence, a reference to Adorno at the outset of a Sibelius book is still in order as an aid to identifying those aspects of Sibelius’s music that have led to the “academic” prejudices against it—even if the level of musical penetration in a casual attack such as “Glosse” is hardly adequate for meriting a lasting influence.

[2] The present anthology testifies to a change of attitudes among “academics.” Of its twelve contributors, seven are North Americans and Britons whereas five are Finns. The essays treat Sibelius’s music from widely variable angles, but, significantly, the majority of them make use of modern analytical techniques, being thus willing to address Adorno’s charge of the inadequate “state of musical material” directly by the close examination of that material. Schenkerian-oriented approaches are well represented. This is quite appropriate since an important aspect of Sibelius’s art is his relationship with the past, his position as one of the last representatives of the great tonal tradition. Moreover, whereas the surface of Sibelius’s music made the impression of “senseless juxtaposition” in Adorno, Schenkerian reductions—if competently performed—are able to offer demonstration of precisely those “standards of musical quality” that Adorno cherished, “the richness of inter-connectedness” and “unity in diversity,” as being amply present beneath the sometimes fragmentary surface (xviii–xix). But the ability to exploit the large-scale potential of the tonal system is only one facet of Sibelius’s accomplishment. Whereas Adorno charged Sibelius both with the defective command of traditional techniques and with the failure to keep in touch with later advances, both charges may be contested by analytical examination. With reason the editors speak of a “combination of progressive and conservative aspects” in Sibelius’s “Janus-faced” music (xv); the advanced “state of musical material” is also evident in aspects reflecting contemporary modernistic trends and even pointing to the future. In this review, I concentrate on the analytical and theoretical perspectives brought up in Sibelius Studies, treating first the essays involving Schenkerian methods and proceeding then to discuss the more “progressive” aspects in Sibelius’s music and their treatment in the present anthology.

Jackson’s Enterprise: Bold Promises—Shaky Groundwork

[3] Since the largest space by far in the collection—100 pages, more than twice the size of the second largest paper—has been allotted to a contribution by one of the editors, Timothy L. Jackson, it is appropriate to begin by commenting on his essay, “Observations on crystallization and entropy in the music of Sibelius and other composers.” In conformance with its size, the scope of the analytical perspectives brought up in this article is impressive. Instead of merely presenting voice-leading reductions of individual movements, Jackson addresses such broader topics as inter-movement organization, historical evolution within a compositional genre, and the relationship between musical organization and extra-musical or programmatic significance—important issues Schenkerians are sometimes charged with neglecting. To illuminate such broad perspectives, Jackson presents analytical graphs of over twenty compositions by various composers—less than half by Sibelius. The present essay may be viewed as a part of a larger project; some of its material has been presented in Jackson’s previous publications.

[4] Jackson writes grippingly and colorfully, making conclusions that seem exciting and, for the most part, logically supported by the analytical graphs. Indeed, at first sight one may get the impression of Jackson’s enterprise as one of the most interesting in the field of analytical research. However, the first and most crucial requirement for any kind of analytical conclusion is that the relationship between the basic analytical entities, such as voice-leading graphs, and the actual compositions be cogent and meaningful. It is with this issue that Jackson’s article has its greatest problems, problems whose quantity and gravity seriously detract from the cogency of his project. While his terminology is conventionally Schenkerian, Jackson’s readings are frequently in blatant contradiction with any normal analytical criteria based on the well-established principles of tonal syntax. Characteristically, moreover, he does little to explicate the grounds even for his most peculiar-looking interpretations, and the reader’s efforts to trace implicit grounds yield no consistent result.

[5] A central notion in Jackson’s essay is that of auxiliary cadence. Of special significance is the “over-arching” type of auxiliary cadence, in which the “definitive tonic arrival” or “DTA” only occurs towards the end of a movement or composition (177, 187–8). The auxiliary cadence serves as a metaphor of crystallization (189)—a concept with evident programmatic potential. As a special theoretical innovation Jackson sets forth the concept of “tonic” auxiliary cadence (188–9). This notion (the apparent contradiction in which Jackson readily acknowledges) refers to a situation in which an initial firm root-position tonic is “devalued and subsumed—in light of subsequent events—within the ‘p’ [pre-cadential chord] of an auxiliary cadence” to some other scale degree (189). This other scale degree may then function in another auxiliary cadence directed towards the “DTA,” occurring later in the work.

[6] The temporal perspectives evoked by the notion of “tonic” auxiliary cadence

are certainly interesting. There is no denying that a significant part of our

musical experience is the sense in which the impressions of structural relationships

change over the course of musical time. And by no means is the opening harmony

devoid of the possibility of being retrospectively reinterpreted or “devalued”—even

if it eventually turns out to be the same chord as the functional tonic. Example 1 illustrates.

Consider the abstract bass lines in its top stave and possible impressions at

time-points (1), (2), and (3). Even if the initial C makes the impression of

being the tonic at time-point (1), under certain circumstances we may experience

it as subordinate to another scale degree (IV or

[7] Despite the interest of such temporal perspectives, one should not lose sight of the fact that the readings in Example 1b do require special circumstances. In what is probably a great majority of cases, occurrences of the bass lines in question give little support for perceiving the harmony at (2)—even momentarily—as the tonic or structurally superior in relation to (1). If the notion of “tonic” auxiliary cadence is to have any descriptive power, it cannot be applied indiscriminately to all instances of such bass lines. This point may appear self-evident, but making it seems necessary since Jackson’s examples do so little to clarify what kind of conditions he actually posits for the occurrence of a “tonic” auxiliary cadence.

[8] Example 2

reproduces relevant parts of Jackson’s first exemplar of this notion, the finale

of Beethoven’s 7th Symphony (his Example 8.6). The graph appears ambiguous as regards

the relative priority of the A in measure 12 and the F in measure 198 (an ambiguity perhaps

intended to reflect shifting temporal perspectives).(2)

Verbally, however, Jackson asserts clearly that “the tonic [

[9] In his discussion of the ‘tonic’ auxiliary cadence, Jackson explains that the identification of this phenomenon “depends entirely upon context” and offers two clues suggesting that an opening tonic is not “DTA” (200). The first of these is “provided by design if its main thematic material is deferred.” The second is the occurrence of the tonic “in the wrong mode, minor instead of major or vice versa.” Leaving aside for the moment considerations of the validity of these clues in tracing prolongational relationships, it may be observed that his first exemplar is supported by neither clue. The tonic is, of course, major right from the start (measure 12), and it is also difficult to see how the thematic design would speak for measure 451 as the “definitive tonic arrival” or “crystallization.” Jackson calls attention to the “tremendous weight on the dominant at the beginning of the primary theme (measures 1–12), while the tonic resolution in measure 12 is relatively ‘weakened,’ almost perfunctory” (201). He fails to mention, however, that the prevalence of the A major tonic continues in a straightforward manner in measures 20–40, supporting material whose “definitiveness” hardly falls behind that of his “DTA” in measure 451. In fact, the material in 451 ff. repeats that in measures 36 ff.

[10] If the A major tonic in measure 12 and measure 20 ff. seems powerful and straightforward

enough to strongly suggest (to say the least) a “definitive arrival,” an even

more puzzling aspect in Jackson’s analysis is the notion of the F in measure 198

as the goal tonic in an A-C-F cadence. One would imagine that overriding

the A as a tonic would presuppose rather extreme means to direct the tonal focus

toward F. In the Beethoven, however, one finds no elements whatsoever to suggest

a tonicization of F major at its appearance or in the events leading to it (whereas

the preceding C is amply tonicized). Moreover, aspects such as orchestration

and dynamics clarify the character of F as a surprise digression from the main

progression C-E; the F supports a pianissimo woodwind episode (measures 198–219)

that humorously foreshadows the fortissimo return of the main theme on E. All

in all, the actual musical circumstances offer no substantiation even for a

V-I relationship between the C and the F (in the manner of Example 1a:ii2),

let alone for viewing the opening A as the III

[11] This example, unfortunately, is not exceptional in its questionable reading

of basic tonal relationships; the second A-C-F “cadence,” spanning

measures 231–321, is by no means more plausible. For an example from another

composition, consider the last movement of Schumann’s Fantasy op. 17, in which

Jackson views the opening C major as initiating a “III-(

Excursion: Salience and Stability in Schumann’s Fantasy op.

17

[12] These examples might suffice to give an idea of the quality of Jackson’s

“Observations,” in general, and of the shaky groundwork of his key concept,

the “tonic” auxiliary cadence, in particular. However, an excursion to one further,

especially interesting example, the first movement of Schumann’s Fantasy, will

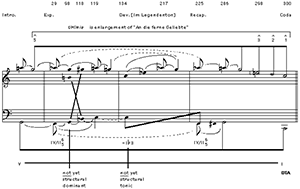

help to bring up some notions of general relevance for analysis. Example 3 reproduces Jackson’s overview of

this movement (his Example 8.2a). This reading, too, contains a tonic devaluation:

the C minor of the middle Im Legendenton section is conceived as the

upper fifth in a huge subdominant prolongation spanning measures 29–225. This

time the clue given by modal mixture (“minor instead of major”) is certainly

present. But, according to Jackson, an “even more compelling” indication of

the structural relationships is “the initiation of the recapitulation on the

same II6/5/

[13] One might remark that if the chord in question is understood as a “IV![]()

![]()

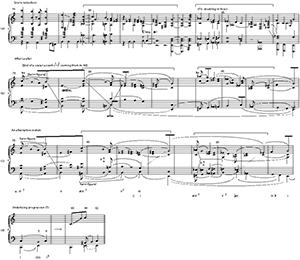

[14] Example 5b is a provisional sketch demonstrating that the first section (exposition) of

the Fantasy does lend itself to an interpretation better justified by the combination

of stability and salience. It contains one very significant exception to the

consonance-dissonance condition since it views the opening V9/7 as prolonged

throughout. Comparing this ninth chord with the chord on F (measure 29), it may be

noted, first of all, that its salience in the Fantasy is certainly still

much greater; hence the salience criterion would not speak for regarding the

return of the V9/7 in measure 98 as “not yet structural dominant,” as in Jackson’s

analysis (Example 3).

What is even more important is that whereas the chord on F (the ![]()

![]()

[15] Incidentally, I would also suggest that there are significant aspects which make the V9/7 itself a special chord type and more than an arbitrary dissonance. First, Schumann had a certain predilection for this chord—which in his usage is often (as in the present case) conceivable as a superimposition of V and II. Second, such chords, emancipated from their dominant function, assumed an even more independent status in the music of Debussy and his generation—including, to some extent, Sibelius. Third, such a historical development is, I would suggest, influenced by the way in which the chord approximates the harmonic series: f2 and a2 correspond to harmonics 7 and 9 of G. Hence, even though the V9/7 is dissonant in the syntax of conventional tonality, its tendency to assume a more stable or independent role may have a (psycho)acoustical basis.(6)

[16] Returning to Example 5b, the ![]()

[17] While the justification for the choice of the framework points in Example 5b seems clear and conclusive, the internal hierarchy within this framework—especially with respect to the D and C basses—is a more difficult issue that I will leave open in this provisional reading. Two alternative interpretations are sketched in Example 5d. As regards thematic design, both D (measure 41) and C (measure 61) are highlighted by similar material, evoking the keys of D minor and F major, respectively. In the recapitulation, the D minor passage is transposed to C minor, parallel of the home key. For these reasons, it would seem more natural to locate the beginning of the “second group” at the D (measure 41) than at the C (measure 61), as in Jackson’s graph (Example 5a).

Limits of Prolongational Thinking?

[18] Although I think that Jackson’s attempts to view the tonics in the Beethoven

and Schumann examples (Example 2, measure 12; Example 3, measure 134) as subordinate to another scale

degree (IV and

[19] In this connection—to get finally closer to Sibelius—I would also question whether a harmonic event such as the auxiliary cadence is the only or even the most pertinent musical metaphor of “crystallization.” In introducing this concept, Jackson appeals to Sibelius’s description of the finale of his Third Symphony as “the crystallization of the idea from chaos” (175).(8) In my view, an “idea” would seem to refer to the thematic-motivic rather than the harmonic-prolongational aspect of organization. The auxiliary cadence certainly involves an effect of harmonic clarification, or “starting at some less definite place and moving toward the point of tonic arrival,” as Edward Laufer put it in his analysis of Sibelius’s Fourth Symphony in Schenker Studies 2.(9) However, thematic crystallization needs also be recognized as a primary form-defining resource in Sibelius’s music—not only the Third Symphony—without any necessary connection with some harmonic progression. If these considerations bring to mind Schenker’s polemical distinction between “fundamental structure” composers and “idea” composers, I would suggest that it is hardly among those of his notions that we should be loyal to.(10) For Sibelius, at least, both aspects are of paramount importance.

[20] I will mention only a few examples showing that the reliability of Jackson’s

analyses by no means improves when proceeding from the tonal tradition to Sibelius.

Lemminkäinen’s Return poses an analytical problem comparable with

the Schumann: it contains an episode in ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

[21] All in all, despite the impressive scope of issues raised by Jackson, the grounds for his analytical readings are so shaky that the conclusions from these readings have little worth in illuminating such issues. And while the project of illuminating Sibelius’s music analytically is very welcome, it is regrettable that the editors of Sibelius Studies showed such a lack of judgment as to assign a lion’s share of the book to such untenable material. Perhaps one might find the raising of important issues as something of a merit in itself. One certainly hopes that Jackson’s article would inspire or provoke more competent analytical work viewing the historical evolution of symphonic music from a structural perspective.

Considerations of Multikey Schemes

[22] The auxiliary cadence warrants consideration also as the basis for explaining

tonal organization in pieces that begin and end in a different key. Despite

convincing exemplars of such an explanation, starting from Schenker himself,

there is no justification for applying it automatically to all multikey schemes

(as seems to be Jackson’s practice).(11)

The interpretation of an entire movement or composition in terms of a unified,

end-oriented harmonic progression is a complex analytical statement that requires

specific factors to support it. Regarding such factors, I would, once again,

emphasize the significance of foreground for understanding background. If foreground

motives or harmonic details are heard as pointing to or “striving for” the final

tonic prior to its decisive arrival, this arrival will be more readily experienced

as a tonal goal having an “organic” connection with the beginning. Such interrelationships

across levels are the more essential the more complex the overall progression

is and the more time it takes to get to the final tonic. Two Chopin examples

illustrate this. In a short piece such as the Prelude op. 28 no. 2, the simple

V-I relationship will “make sense” even though the opening motives in no

way point to the eventual A minor tonic (but rather to the keys of the subsequent

preludes, interestingly enough).(12)

On the other hand, the more complex progression VI-V-I spanning most

of the Fantasy op. 49 gains essential support from foreground elements that

refer to the relationship between the opening F minor and the final

[23] These considerations bear interestingly on Sibelius’s music and its analysis. Two significant works, Lemminkäinen’s Return and Pohjola’s Daughter progress from minor to relative major as does Chopin’s Fantasy. Moreover, just as in the Chopin, the whole-tone emblematic of the key change, ˆ1-ˆ7 in the minor or ˆ6-ˆ5 in the major, features as an important foreground element in both works—one token of their “richness of interconnectedness,” to quote Adorno’s expression. These relationships are observed by Jackson concerning Lemminkäinen’s Return (219) and by Timo Virtanen in his special chapter on Pohjola’s Daughter (169). In these works, viewing the key relationships in terms of end-oriented progressions seems concordant with their musical effect and also with the programmatic content of “homeward journey.” However, these progressions may not be literally auxiliary cadences since there is no dominant linking the VI and the I—unless the first occurrence of the latter is regarded as non-structural.

[24] Virtanen’s and Jackson’s readings of Pohjola’s Daughter contrast

in this respect. Virtanen views the arrival at the

[25] Virtanen’s discussion on the relationship between the program and the musical structure is illuminating and nuanced. However, the informative value and persuasiveness of his analysis, too, would have profited from a closer consideration of details; his graphs only show the background and deep middleground levels (Example 7.5). As will be discussed below, there are quite nontraditional aspects in the compositional technique of Pohjola’s Daughter and it would have been worthwhile to flesh out whether and how such aspects can be related to a linear construct emerging from the tonal tradition such as the Ursatz. Having said this, I have to add that the pacing and weighting of structural events in Virtanen’s analysis appears by no means counterintuitive. To be fair, it should also be observed that Virtanen’s focus is not only on analysis but on sketch studies as well.

[26] That multikey schemes cannot always be so convincingly explained as embodying

a unified, end-oriented harmonic progression is exemplified by the symphonic

ballad The Wood Nymph (Skogsrået)—an early work (1895)

recently “rediscovered” with great public attention after over half a century

with few performances. Its lack of clear tonal orientation is reflected in the

two readings of this composition in Sibelius Studies. Whereas Jackson

sees the piece as embodying a

[27] (In this connection I would suggest that while the distinction between absolute and programmatic music is not clear-cut, a relative distinction remains essential for understanding Sibelius. For the symphonies, one could perhaps, at best, invent programmatic interpretations—Jackson attempts this—that are concordant with the musical experience but would add nothing essential to it. For the symphonic poems and Pohjola’s Daughter—a “Symphonic Fantasy”—programmatic considerations may considerably illuminate passages that otherwise seem strange. Finally, a melodrama-based work such as The Wood Nymph makes little sense without knowing the program depicted in the poem.)

[28] These considerations bear on the evaluation of the aesthetic quality and

the recent reception of The Wood Nymph. Murtomäki begins his article:

“The performance in 1996 of [

Laufer’s Case Study: Inspiration and Realism

[29] What may be regarded as the most substantial analytical contribution in Sibelius Studies is its final chapter, Edward Laufer’s “Continuity and design in the Seventh Symphony.” While Laufer’s aims are more modest than Jackson’s, the discussion of the musical material in a single one-movement piece, he accomplishes immeasurably more by the careful and insightful consideration of that material. The complexities in this symphony are formidable; neither the composition nor the unraveling of them is a small feat. And even if we are ultimately to aim at more comprehensive historical comparisons, they become possible only after such careful case studies.

[30] The inclusion of Laufer’s analysis in Sibelius Studies is welcome for promoting both Sibelius among Schenkerians and Schenker among Sibelians. Sibelius Studies is a book likely to have readers with little previous experience in Schenkerian analysis. In such readers, Jackson’s paper may create the impression of “Schenkerianism” as an approach drawing its conclusions from abstract large-scale relationships between more or less arbitrarily chosen notes, with no substantiation in the concrete “surface” material or in the principles of tonal syntax. Laufer’s study is appropriate to dispel any such impression. His attention to “surface” is amply manifest in the meticulous foreground graphs that pervasively accompany the large-scale readings.

[31] Laufer’s analysis combines inspiration with realism. To the intuitions of Sibelians, Adorno’s charges of “senseless juxtaposition” have never made much sense, but it is a joy to encounter such a thorough analytical rationalization of such intuitions (spiced, characteristically, with frequent exclamations of admiration). As for Schenkerian analysis, it would seem that Laufer’s experience with this approach has yielded, aside from the admirable command of it, a realistic view of its explanatory scope. One is almost surprised by the share of “non-Schenkerian” observations in his paper, that is to say, motivic and other surface relationships not supported by any parallelism in the voice-leading structure. I feel tempted to say that, pace Schenker, Laufer values the fundamental structure less for its own sake than for the substratum it offers for the development of ideas.

[32] After Jackson’s obsession with tonic devaluation, it was something of

a relief to see several genuine tonics within the overall organization. What

should be observed, however, is the nuanced way Laufer discusses a variety of

tonic and tonic-like effects. There are, naturally, non-structural “tonics,”

subordinate to another harmony—but even such a harmony may suggest “the

sound (but not the meaning) of the tonic” (372). If such subordination

is not the case, a tonic may function in “a parenthetical insertion within the

larger musical direction—as if two interpretations, the continuous and

the discontinuous, were superimposed.” (376) The interaction of tonal-harmonic

functions with modal and thematic features is lucidly captured in Laufer’s description

of the effect of “main section II,” (measure 222 ff.). Although the tonic is here

neither non-structural nor parenthetical, “in terms of the larger formal plan,

this section is transitory [

[33] In general, Laufer’s readings are cogent and revealing. While he makes

few references to the previous analytical work on the Seventh Symphony, its

future analysts would do well to consult Laufer’s paper. At points, alternative

interpretations come to mind (which, of course, is nothing that could or should

be avoided). Some of these concern apparent repetitions of similar material

which Laufer interprets in radically deviant ways. I do not wish to suggest

that he does not have grounds for such deviations. Nevertheless, I think that

for the majority of readers such grounds are not evident and these readers would

have gained from making them evident. (If such discussion was omitted for reasons

of space, this makes the “self-generous” editorial policy all the more regrettable.)

One such instance occurs in the climax of “main section I,” shown as score reduction

in Example 6a.

Example 6b aligns Laufer’s reading (from his Example 12.2.4) with the score. The

passage in measures 84–86 is a varied transposition of measures 80–82, but Laufer

interprets it quite differently; see brackets. In measure 80, he shows the outer-voice

Bs in the unaccented ![]()

[34] Perhaps the most surprising detail in Laufer’s reading is, however, the

high status of the bass C in measure 80, shown as supporting the top-voice G. The

preceding

Aspects of Modernism

[35] The less conventional features in Sibelius’s music include both those related to the general trends of contemporary modernism and those whose cultivation belonged more specifically to his personal style—but which might, to some extent, be seen as adumbrating some later trends. The former group contains aspects such as modal/scalar/pc-set material, motivic organization, and harmonic usages. In Sibelius Studies, the mode/scale/pc-set issue is focused on by Elliot Antokoletz, who examines the interaction of different diatonic and cyclic-interval (whole-tone and octatonic) resources in the Fourth Symphony, drawing a parallel with composers such as Bartók and Stravinsky (297). A central concern for motivic relationships is a trait Sibelius shares with several of his contemporaries. In Sibelius Studies, the most comprehensive motivic study is Laufer’s analysis of the Seventh Symphony; however, in accordance with the work itself, this study is less pertinent to the role of motives in modernism. Laufer’s basic figures are “rather unassuming” (358) common diatonic figures: intervals, scalar fillings, and turns; only the careful consideration of their moment-by-moment transformation substantiates their work-specific significance. That the Symphony grows out of such material tells much about its special character as an essay on diatonicism (not only in but on C major). The tonally more radical Fourth Symphony might have been cited also as an example based on more “high profile” or individual motives, which, rather than arising from a traditional tonal substratum, assume an active role in influencing tonal relationships. The way in which work-specific motivic forces partly substitute for tonal forces as agents of coherence suggests a point of contact with Schoenbergian thought. Incidentally, it is partly thanks to such “high profile” motivic work that Sibelius remained as an important source of influence for the symphonic work of dodecaphonists of later generations such as Joonas Kokkonen and Paavo Heininen—music little known outside Finland but, in my view, much more worth listening to and promoting than pieces such as The Wood Nymph.

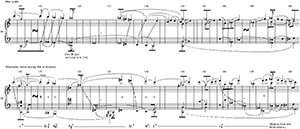

[36] Regarding Sibelius’s harmonic usages and their relationship with

the trends of early 20th-century music, I will discuss only one passage from

the Seventh Symphony (measures 107–49). Laufer observes the use of “characteristic

Sibelian ninth-chord sonorities” in measures 115–8, adding that “[t]hese are

only apparent ninth chords”; they are brought forth by “rhythmic shifts [

[37] Laufer’s interpretation implies that ninths are assumed to have their

conventional status as dissonances. Such an assumption is by no means implausible

since other parts of the symphony show clear 9-8 resolutions. Significantly,

however, in measures 107–47 the harmonic organization may be described as based

entirely on transpositions of this ninth chord—before the dramatic arrival

in measures 148–9 at a rhythmically varied repetition of earlier material (measures

88–89). Such an extended prevalence suggests considering this chord as

something more than “apparent.” Example 7b shows an alternative reading based

on the assumption that the ninth is momentarily “emancipated” from its dissonant

status to become structurally supportive. This reading shows a much simpler

relationship with the actual events and their articulation. In measures 107–133

the bass traverses from C to C through a descending whole-tone scale, articulated

in two parallel halves, C-

[38] It should be noted that this kind of use of parallel ninth chords was by no means innovative in 1924 when the Seventh Symphony was completed. Similar techniques were employed by composers such as Debussy and Scriabin some two decades earlier. The analytical problem of the extent to which the triadic norms of consonance etc. can be assumed to underlie linear progressions in music that momentarily appear to manifest another kind of consistent organization has relevance for a large body of early 20th-century music.

[39] Among the unconventional Sibelian features that are less closely connected with general contemporary trends, we may identify aspects of Satztechnik and form. By Satztechnik I refer generally to the basic harmonic and contrapuntal principles underlying the formation of surface textures, which, in the tonal tradition, include outer-voice counterpoint, thorough bass, and I-V polarity. Sibelius’s music is, at times, far removed from these principles, even when the scalar material is diatonic and in that respect makes a less “modern” impression. This kind of nontraditionalism is essential for understanding Adorno’s characterization of Sibelius: “‘themes,’ some completely unplastic and trivial successions of pitches, are put forth, most of the time never once harmonized, instead unisono with organ points, stationary harmonies and whatever else the five-line staff will produce in order to avoid logical harmonic progression” (cited in xviii). Hence, to Adorno and his followers, Sibelius was nontraditional in a wrong way—but, to be sure, Adorno’s negative aesthetic judgement is invalidated by his inability to perceive and appreciate the compensating accomplishments in aspects such as multi-level motivic relationships and novel temporal effects.

[40] As a demonstrative example of Sibelius’s nontraditional Satztechnik,

one may consult the opening of Pohjola’s Daughter. As described by Virtanen,

“the center of gravity is shifted almost imperceptibly from the G minor to the

[41] The nontraditional features of Satztechnik have important ramifications

for analysis. If the traditional principles of Satz do not prevail, we

may ask how this should be allowed for in applying a method deeply rooted in

these principles such as Schenkerian analysis. This issue is not systematically

discussed by Schenkerians in Sibelius Studies, although Laufer does point

out characteristically Sibelian practices of ellipsis, shifts, anticipations

and the like, relating thus the apparently nontraditional with the traditional.(18) However, as with the ninth chords discussed above, there is reason to ask where

we should place the borderline between “apparent” and “real” nontraditionalism,

in other words, at what point we gain a better insight of the music by treating

the previously exceptional as having become normative. Since Sibelius never

totally abandonded traditional means, a double perspective is, generally speaking,

recommendable. To cite one example, Laufer reads an evaded ![]()

[42] Form is often considered as the main progressive aspect in Sibelius’s music. The conventional wisdom—at least here in Finland—is that while Sibelius after the Fourth Symphony ceased to follow the general trends of contemporary modernism with respect to pitch material, this was compensated for by the ongoing cultivation of innovative formal language. This contrasts with Schoenberg’s music, in which, to cite the editors, “conservatism in rhythmic and formal dimensions sometimes counterbalances radicalism in the post-tonal harmonic language” (xv). Against these considerations, the treatment of form in Sibelius Studies is, at times, something of a disappointment. The description of form is often based on traditional schemes such as sonata form, rondo, and, in Jackson’s paper, “super-sonata,” even when matching Sibelius’s imaginative treatment of form would require more imaginative analysis. For example, Antokoletz’s description of the third movement, Il tempo largo, of the Fourth Symphony as a “sonata allegro” (313) seems rather insensitive to its essential features in both the thematic and the tonal-harmonic respect. I would cite this movement as one in which Sibelius is at the height of his powers with respect to progressive pitch material, motivic concentration, as well as formal originality (to say nothing about emotional depth)—properties that make it, in my view, one of the greatest accomplishments not only in Sibelius’s output but in twentieth-century music in general. Its form may be described as an archetypal exemplification of thematic crystallization: melodic “well-shapedness” is employed as a key “parameter” that reaches its apex near the end (measures 82–87). Such a view of its form is by no means my contribution but represents “conventional wisdom.” Perhaps, however, such “wisdom” is less self-evident for the international readership; therefore more comprehensive discussion on Sibelius’s characteristic formal practices—from small to overall scale—might not have been out of place in a book like Sibelius Studies.

[43] Two essays in Sibelius Studies deal expressly with aspects of form. In accordance with the above considerations, Tim Howell’s “‘Sibelius the Progressive’” cites “Sibelius’s control of musical time scale” as “perhaps the single most progressive aspect of his compositional technique” (55). He suggests parallels between the “forward-looking characteristics of Tapiola” (ibid.) and the “manipulation of sound masses in the music of Ligeti” (56) and “comparisons between the formal processes of the Seventh Symphony and Elliot Carter’s Concerto for Orchestra” (ibid.). The “amorphous” qualities of Satztechnik pointed out above may also be seen as distantly related with “sound masses.” However, even if there is some resemblance between Sibelius’s nontraditionalism and the above-mentioned avant-garde trends of the 1960s, this is hardly based on an influential relationship. The outspoken avant-garde admirers of Sibelius mentioned by Howell represent more recent decades. On the other hand, more conscious influence of Sibelian formal thinking could be found in the music of Finnish modernists—such as those mentioned above.

[44] More specified notions for the treatment of form in Sibelius are set forth

by James Hepokoski. In his interesting discussion, Hepokoski recognizes Sibelius’s

conscious “shift away from traditional Formenlehre structures” (322)

and offers the concepts of rotational form and teleological genesis

for coping with characteristically Sibelian procedures. Rotational form means

“a structural process within which a basic thematic or rhetoric pattern [

[45] There is no doubt that these concepts are productive in Sibelius analysis.

However, while Hepokoski’s application of them to the finale of the Sixth Symphony

is illuminating, some questions might be stated as to what actually distinguishes

a rotation from a non-rotation, in other words, as to the relative importance

of elements suggesting repetition, on the one hand, and contrast, on the other.

As pointed out by Hepokoski, the opening motives, i.e., those in Rotation 1

(measures 1–16), “supply most of the raw materials for the peak moment, although

they are not yet sounded in telos order” (341); this order is only achieved

in Rotation 3 (measures 55–82). However, if the order of elements is changed,

one may wonder the extent to which one can still speak of a repeated “rhetoric

pattern.” On the other hand, the closing Rotation 9, “one of whose points is

to demonstrate the valedictory abandonment of the rotational principle altogether”

(349), bears a slightly closer relationship with previous material than Hepokoski

assumes. As observed by him, “the concluding portion of Rotation 8 (measures 205–20)

functions as a rhetorical (not a tonal) reprise of the whole of Rotation 1 [

[46] Finally it should be stated that the present review is not meant as a balanced overview of Sibelius Studies, but as a commentary on its main analytical and theoretical perspectives. In addition to such perspectives, those interested in Sibelius will find discussion on topics such as semiotics, discography, programmatic and biographic issues, incidental music, sketch studies, and metrical revisions. And while the editors are to be criticized for how they have chosen and weighted their analytical material, we may thank them for having compiled this book in the first place to offer some kind of picture of the present state of Sibelius research.(20)

Olli Väisälä

Sibelius Academy

PL 86

00251 Helsinki

Finland

ovaisala@siba.fi

Footnotes

1. The progression in Example 1b:i does not literally fulfill Jackson’s definition of “tonic” auxiliary cadence, as cited here, since the initial C is devalued as the dominant rather than as a pre-cadential chord; however, it would seem reasonable to apply the term also for this case. One example of this progression occurs at the opening of Beethoven’s “Kreutzer” Sonata, according to Lauri Suurpää’s analysis, presented at the Third International Schenker Conference in New York, March 1999.

Return to text

2. To depict temporally changing impressions of structural

relationships, it is probably less advisable to mingle them in a single graph

than to provide separate graphs, as is done, for example, in Peter Smith, “Structural Tonic or Apparent Tonic?: Parametric Conflict, Temporal Perspective, and a Continuum of Articulative Possibilities,” Journal of Music Theory 39/2 (1995): 245–84.

Return to text

3. Fred Lerdahl, “Atonal Prolongational Structure,” Contemporary Music Review 4 (1989): 65–87; Joseph Straus, “The Problem of Prolongation in Post-Tonal Music,” Journal of Music Theory 31 (1987): 1–22.

Return to text

4. In Jackson’s graph, the location of the parentheses in measure 61 is unclear. I have “diplomatically” corrected their location in my reproduction. Similar corrections are tacitly made elsewhere.

Return to text

5. In Nicholas Marston’s analysis (which Jackson quotes in his note 34) this C assumes an even greater structural weight (Nicholas Marston, Schumann: Fantasie, Op. 17 [Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992], Example 4.7). The only—but certainly not sufficient—reason for such a reading I can think of is that the inner-voice theme introduced in measure 34 ff. is later, in different harmonic and metric circumstances, employed to establish the C minor (measure 133 ff.).

Return to text

6. By a “psychoacoustical basis,” I refer to the

model of harmonic roots based on virtual-pitch perception; see, for example,

Richard Parncutt, “Revision of Terhardt’s Psychoacoustical Model of the Root(s)

of a Musical Chord,” Music Perception 6 (1988): 65–94.

Return to text

7. This correspondence between large and small scale is observed

by Marston (Schumann: Fantasie, Op. 17; 54, Example 4.7). According to Marston

the connection goes on to the ascending notes D-E-F, for which I find

less justification.

Return to text

8. Jackson’s quotation, taken from Robert Layton’s translation

of Erik Tawastsjerna’s biography, reads actually “the crystallization of ideas,”

in plural. This seems to be a translation mistake since both the Finnish and

Swedish versions of the biography use singular.

Return to text

9. Edward Laufer, “On the First Movement of Sibelius’s Fourth

Symphony. A Schenkerian View,” in Schenker Studies 2, ed. Carl Schachter

and Hedi Siegel (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1999), 136–7.

Return to text

10. Heinrich Schenker, Free Composition [1935], trans. Ernst Oster (New York: Schirmer Books, 1979), 27.

Return to text

11. For discussion on multikey schemes, see, for example,

William Kinderman and Harald Krebs (ed.), The Second Practice of Nineteenth-Century Tonality (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press, 1996).

Return to text

12. For Schenker’s graph of this prelude, see Free Composition, Fig. 110a:3.

Return to text

13. Carl Schachter, Unfoldings (New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), 260–88; see especially Example 11.4.

Return to text

14. Free Composition, Fig. 13.

Return to text

15. Jackson goes so far as to call The Wood Nymph

“a remarkable example of super-sonata form” (215). I find it difficult to trace any sonata-form features with respect to either thematic disposition or harmonic structure.

Return to text

16. Jackson shows E as the governing bass tone from measure 82

(I6) to measure 495 (III) (Example 8.30). As regards the significance of E, his intuitions

might be credited with being on the right track, even if the rationalization

of these intuitions in terms of prolongational superiority is totally misguided.

Return to text

17. This small-scale C-

Return to text

18. Such techniques and their historical precedents are

discussed in greater detail in Laufer’s previous essay “On the First Movement

of Sibelius’s Fourth Symphony.”

Return to text

19. In the Seventh Symphony, too, there is an important

“rotational” relationship that partly involves an inner voice, between measures 34–59 and 64–91. In measures 34–45 and 64–75 the relationship becomes evident by comparing the voices of second violin and first horn, respectively. From measures 46 and 76 onwards it concerns the top or most prominent voice.

Return to text

20. For another representative example of recent Sibelius

research one may consult Sibelius Forum: Proceedings from the Second International

Jean Sibelius Conference, Helsinki November 25–29, 1995, ed. Veijo

Murtomäki, Kari Kilpeläinen, and Risto Väisänen (Helsinki:

Sibelius Academy, 1998). As regards discussion of the formal language in Sibelius’s

symphonies, an indispensable source is Veijo Murtomäki, Symphonic Unity:

The Development of Formal Thinking in the Symphonies of Sibelius, Studia

Musicologica Universitatis Helsingiensis 5 (Helsinki: University of Helsinki,

1993).

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2002 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Timothy Koozin, Co-Editor and Tahirih Motazedian, Editorial Assistant