Review of Ellie M. Hisama, Gendering Musical Modernism: The Music of Ruth Crawford, Marion Bauer, and Miriam Gideon (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001)

Judy Lochhead

Copyright © 2003 Society for Music Theory

[1] Ellie Hisama’s Gendering Musical Modernism: The

Music of Ruth Crawford, Marion Bauer, and Miriam Gideon (henceforth

GMM) was published in 2001 as part of the “Cambridge Studies in Music Theory

and Analysis,” a series edited by Ian Bent. Hisama’s book offers analyses of

specific works by Crawford, Bauer, and Gideon with two interrelated goals: 1) to

link musical design to each composer’s “identity” and 2) to “inform” the

analyses “by the conditions of gender and politics within which [the music and

the composers] exist.” (page 2) In his introduction to the series, Bent surveys

the field of study it encompasses in order to situate GMM. Outlining a

field in which the strands of “analysis” and “theory” twine together in

practice, Bent locates Hisama’s book on the analytical strand but also

characterizes it as a “critique of the place of women in

[2] Bent’s introduction defines analysis as a type of musical study that can either stand alone as an explanation of how a particular piece of music “works” or serve as a tool for music theory or history.(2) As a tool for music theory, analysis is the means by which one generates “data” or “facts” about pieces; the theorist, generalizing from such gathered information, develops a systematic theory to explain musical structure. As a tool for music history, analysis is the means by which one discerns information about particular pieces or groups of pieces in order to trace broad categories of similarity (such as genre or form) or processes of change (historical development).

[3] From the perspective of Bent’s typology for music analysis, Hisama’s GMM does not fit comfortably into either the “stand alone” or “tool” categories. Hisama’s project does not offer “stand alone” analyses of particular works nor does it link works together through observed features of musical design. Rather, the project designs “close readings” of particular pieces from information about a composer’s biography and the conditions under which she worked. Like a good amount of recent scholarship which proceeds from a composer’s social and intellectual context toward an understanding of musical design and compositional choice, Hisama’s project calls into question Bent’s typology. The directionality of such recent scholarship, from context toward design, has in recent years opened up new vistas onto musical creativity, compositional intention, and listening. And while Bent’s qualification of Hisama’s project as “critique” already hints at the limitations of the categories, the typology that underlies his series does not easily contain a project premised on the possibility of tracing a line from social and intellectual circumstances to the design of a specific aesthetic object.

[4] My review of Hisama’s GMM proceeds from the issues raised by its challenge to Bent’s typology of music scholarship and addresses two broad questions: What is the nature of Hisama’s approach to an analytical understanding of the pieces studied in the book? And, what kinds of ramifications do her analyses have for musical understanding in its historical and structural guises?

[5] The three women whose music is the focus of Hisama’s analyses were active professionally during the middle to later years of the 20th century. Their birth and death dates are: Bauer, 1887–1955; Crawford, 1901–53; and Gideon, 1906–96. All were affected by changing attitudes toward and expectations for women as professional and creative agents that arose in the early years of the 20th century, but only Gideon would have witnessed the significant institutional changes that were brought about by the Women’s Movement of the 1970s.

[6] The specific works Hisama analyzes are: Crawford, movements three and four of the 1931 String Quartet and the song “Chinaman, Laundryman” from the Two Ricercari for voice and piano of 1932; Bauer, “Chromaticon” and “Toccata” from Four Piano Pieces of 1930; and Gideon, “Night is My Sister” from Sonnets from Fatal Interview for voice and string trio of 1952 and “Esther” from Three Biblical Masks for violin and piano of 1960. Each of the analyses begins with an account of the social and personal circumstances contextualizing the creation of the music, including: 1) relations of power between different contemporaneous social groupings based on race, ethnicity, sexuality, and gender, and 2) political and economic realities of the time. These circumstances establish the basis of a particular narrative of musical structure that is revealed through an analytic interpretation of the music. I give a more detailed account of two analyses and summarize the approach and findings of the others.

[7] Crawford, Third Movement of the String Quartet

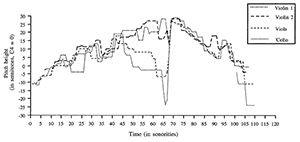

Figure 1. Hisama’s Figure 2.1 (p. 21) Graph of Crawford, String Quartet, third movement

(click to enlarge)

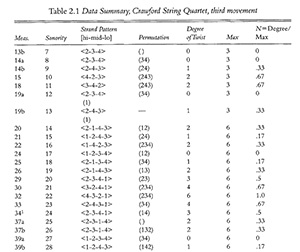

Figure 2. Excerpt of Hisama’s Table 2.1 (p. 27) Data Summary: Crawford String Quartet, third movement

(click to enlarge)

[7.1] Starting from documentary evidence of Crawford’s dissatisfaction with her treatment as a “woman composer” from her male teachers and colleagues, Hisama offers an analysis demonstrating how her dissatisfaction is embodied in musical structure. The analysis focuses on how the “voices” of the string quartet move with respect to one another. Premised on a “normal” registral disposition of voices, the analysis traces the degree of voice crossing or “twist” that occurs over the course of the movement. The disposition of voices is defined not by fixed registral spaces but rather by relative values of higher or lower. Hisama represents these voice dispositions in two kinds of ways. First, a two-dimensional visual model of voice “twisting”, reproduced here as Figure 1, shows the pitch variation of each voice over time. And second, Hisama provides a statistical tracking of the instances of voice crossing in any given sonority throughout the movement. Dependent on numerical modeling and a notion of a dispositional norm, this type of representation allows for a distinction of “degree”. For instance, a twist of “0” is defined by a sonority whose registration has the cello lowest, viola above the cello, violin 2 above the viola, and violin 1 highest. A twist of “1” would entail any inversion of this relative registration: e.g., from low to high, viola-cello-violin 2-violin 1. (See Figure 2).

[7.2] This modeling of relative voicing of sonorities allows Hisama to trace the changing values of twist throughout the movement. She observes that these varying degrees of twist articulate a design based on a series of relatively short cycles.(3) The cyclical design observed through degree of twist operates in counterpoint to a more traditional “arch” narrative of climax that also occurs in the movement by virtue of phenomenal characteristics of absolute pitch height, dynamics, and textural activity. The design of climax is understood by Hisama and others to function within a traditional musical discourse—a discourse associated with male dominance; the cyclical design articulated by degrees of “twist” poses an alternative and subterranean structure. The movement thus has a “double-voiced discourse,”(4) in which a narrative of “resistance” may be understood to operate within a more normative discourse-the “normative” occurring on the “more prominent narrative of the music’s surface” and the resistance occurring in another “musical space”. (page 34) For Hisama, the operation of both types of discourse—that of climax in the phenomenal space of dynamics, texture, and register and that of cycles in the subterranean space of “twist”—is an indication that Crawford exercised creative control not simply by inscribing an alternative discourse but further by subverting the dominant discourse. That is, the operation of the discourse of cycles “foils” or diminishes the effectiveness of the discourse of climax.

[8] Crawford, Fourth Movement of the String Quartet and “Chinaman, Laundryman”

[8.1] Unlike the analysis of the Quartet’s third movement for which she devises a method to reveal degree of twist, Hisama relies on an existing procedure for her analyses of the Quartet’s fourth movement and for the song “Chinaman, Laundryman.” Using contour theory as defined by Robert Morris (and with additional ideas from Friedmann and Marvin and Laprade), Hisama develops a narrative reading from the data generated by this theoretical model.(5) In the Quartet movement, an ongoing disparity between the “prime contours” of a “female” and “male” line suggest that the “female” part or line is “independent, assertive, and daring” (page 58) in its exchange with the male line. In the song, instances of contour “deviance” from a norm musically inscribes the Asian launderer’s resistance to the authority of the dominant culture. In both analyses, the narrative of social and personal resistance is read through the numerical data generated by contour theory which allows for the observation of similarity and difference.

[9] Bauer, Toccata

[9.1] Hisama’s analysis of the Toccata builds upon circumstantial evidence of Bauer’s sexual orientation as a lesbian and a concept of “non-power” articulated by Suzanne Cusick that takes account of lesbian forms of relationship.(6) The analysis focuses on the pianist’s hand positions as would occur in a performance of the music. The hands are frequently positioned close to one another in the Toccata and often the left-hand moves over the right, challenging a normal, non-crossed position. Hisama, following Cusick, reads the hand positions as a metaphorical enactment of bodily positions in sexual encounters: who is “on top” and who “on the bottom.” The power implicit in sexual “superiority” is called into question by lesbian relations and the “crossed” positions of the right and left hands of the Toccata embody the lesbian challenge to the social norms of sexual relations.

[9.2] Hisama uses a numerical model to formulate differing hand positions, assigning lower numbers to the left-hand and higher numbers to the right-hand. Many of the sonorities of the Toccata entail dyads in each hand, thus the left hand takes numbers 0 and 1 and the right hand 2 and 3. In these instances, all possible positions are represented by some permutation of the numbers 0–3. This numerical modeling permits Hisama both to name particular hand-positions and to tabulate the number of occurrences of each possible one. The tabulation of occurrences allows Hisama to observe the frequency in which positions occur and to establish the <0213> position as a norm since it occurs most often. However, the statistical aspects of numerical modeling play only a small role in Hisama’s interpretation; the focus of the analysis lies in a narrative in which the differing hand-positions are the “subjects” of the story. The narrative takes account of the changing nature of interaction between these subjects and ultimately demonstrates relations that “permit the flow of power from one party to the other and back.” (page 121)

[10] Bauer, “Chromaticon” and Gideon, “Night is My Sister” and “Esther”

[10.1] The analyses of each of these three works involves a narrative in which some musical object becomes the subject of a story that correlates with some aspect of the composer’s life. Linking “Chromaticon” to Bauer’s explicit concern for “equality between unequal groups” (page 125), Hisama’s analysis tells the story of a motive which “fends off repeated challenges,” eventually retaining a position of authority. To tell the story, Hisama uses contour and set theory as tools for describing the subjects of the story. Gideon’s “Esther” musically depicts the transformation of the biblical character Esther from an indecisive and passive to a forceful and authoritative woman. Hisama links the story of Esther to Gideon herself, suggesting that this transformation was something she herself desired and that she inscribed the process in the music of “Esther.” The analysis personifies the violin as the character Esther and traces the story in two ways. First, Hisama demonstrates how the phenomenal characteristics of the violin, including features of register, dynamics, articulation, and rhythm, depict a transformation from “tentative” to “bold and assertive.” (page 168) Second, Hisama shows how the violin’s relation to the piano’s music changes from one of dependence to one of independence. To tell this musical story, Hisama uses the descriptive tools of set and contour theory.

[10.2] Gideon’s “Night is my Sister” uses a poem from a 1931 collection by Edna St. Vincent Millay. The collection, taking a female perspective and voice, tells about a woman’s tumultuous love affair with a man. In the poem, the woman, reflecting on her own drowning, berates the man for his failure to rescue her. Hisama’s analysis shows how Gideon’s musical setting of the text depicts the pathos of the woman’s situation and the apathy of the man. The analysis focuses on how features of voice-leading, doubling, meter, and texture “paint” the story of the poem, using set and contour theory and traditional terminology as the means to demonstrate how sound correlates with verbal meaning. Further, Hisama argues that the song’s musically-inscribed sympathy with the woman of the poem stands as evidence of Gideon’s concern for the plight of women as creative agents, despite her refusal to identify as a “woman composer.”

[11] The analyses that form the core of GMM are grounded in a variety of different analytic approaches. Hisama employs both i) established techniques for identification and formulation of pitch groups and of a musical object’s contour and ii) traditional terminology for describing voice-leading, doubling, rhythm, and texture. For the analyses of Bauer’s Toccata and of the third movement from Crawford’s String Quartet, however, Hisama devises new techniques based on numerical modeling of musical relationships: in the first instance for describing “hand position types” and in the second, for revealing a new concept of “twist.” All of the analyses involve a structural narrative that traces musical entities over the course of the movement or piece, casting them into a musical story that entails a dramatic curve or plot. The structural narrative provides the basis for connecting musical design to the composer’s identity within a contextualizing social framework.

[12] As I suggested earlier, the directionality of this sort of inquiry, from biographical and social context toward musical design, sheds a new light on our understanding of how music reflects and enacts the conditions of its production and reception, but it also raises a number of questions about the role of music analysis in revealing music’s immersion in human existence. These questions have to do with the way that an analytic approach “shapes” the analytic result and with the historical and structural ramifications of analytic interpretation. A return to Bent’s typology provides entry into these issues.

[13] The seven “close readings” of works by Crawford, Bauer, and Gideon that constitute GMM provide the grounds for its inclusion in a series on the “theory and analysis” of music. But the challenge that Hisama’s work poses to Bent’s typology is telling. It is based on the observation of what kind of function “an analysis” has: it can stand alone as a revelation of how a piece works through observation of its “factual” details, or it can serve as a tool for revealing “facts” about musical organization in order to make historical or theoretical claims. While not explicitly, the typology implies that analytic observation generates objective information—“fact”—which is then subject to interpretation. As Mary Poovey has convincingly argued, “facts” are epistemological units that have a history and function as a possible—i.e., not a necessary— mode of representing the world.(7) In Poovey’s terms, then, the “facts” generated through analysis about musical structure are units of knowledge arising from historical practices of representing the world: analytic facts are not universal truths about the musical object.

[14] The nature of the epistemological status of analytic facts is intimately related to the general goals of scholarship moving from context toward design. This scholarship, of which Hisama’s project is an excellent example, stands in opposition to other sorts of musical study which are premised on notions of music’s autonomy, on its status as a universal language. The directionality of scholarship such as Hisama’s is grounded in the belief that an understanding of music must take into the account the historical and social conditions of its creation and reception. However, while it is relatively easy to deny music’s autonomy and universality, the task of moving from context toward design raises some obstacles—obstacles related to the practice of analysis and to the status of the “facts” that it generates.

[15] The problem of demonstrating that and how music both reflects and enacts the conditions of its production and reception may not be separated from the issue of analysis since it is through the descriptive methods of analysis that any kind of assertion about music is made. Following Poovey: analytic techniques, terminology and concepts do not transparently reveal musical structure; rather, they construct the particular ways it is manifest. Over the last twenty-five years, a number of scholars have been engaged in an ongoing critique of analytic discourse, specifically on how the discourse is grounded in particular systems of belief. Notable in this regard is the work of McClary, Maus, Cusick, Kerman, and Treitler.(8) And, particularly relevant here is the suggestion that not only specific terms and concepts but also whole systems of analysis play a determinative role in what may be observed about music.

[16] To conclude this review, I consider the questions raised when this determinative role of analysis is set against the goal of demonstrating how a particular work reflects and enacts composer identity and social context. Returning to Hisama’s analysis of the third movement of Crawford’s String Quartet, I focus on two issues: 1) “how” an analysis is formulated and 2) “to whom” analytic observations are intended.

[17] For me, Hisama’s analysis of the third movement of Crawford’s Quartet is the most intriguing and imaginative one of the book. Yet, while I find the analysis intellectually fascinating, when I listen I have difficulty feeling the presence of her modeling of the string quartet voices in terms of “twist” and “cycles.”(9) The concept of “twist” has a visual presence on the page (as my Figure 1 attests), and it may be observed in the numerical and statistical representation that Hisama devises. But its aural presence is undermined by the timbral similarity of the voices of a string quartet. Further, since the whole movement is characterized by a series of long durations and staggered entrances amongst the four parts, there is no aurally clear sense of line independence as required by a model of “twist.” The concept of cycle that runs in counterpoint to the discourse of climax raises similar questions. Those cycles emerge from the numerical representation of voicing as “degree of twist,” and since the concept of cycle is dependent on the concept of twist, the question of presence arises here as well. At issue is the nature of the analyst’s perceptual engagement with the piece and of the mode of representing that engagement. Visual perception of the score of Crawford’s quartet can confirm the model of twist, an aspect of the music that is corroborated by Hisama’s visual modeling in the figure cited above. Further, the decision to represent “twist” numerically predisposes observation toward questions of “degree” which in turn allows cyclical patterns of degree to emerge. In other words, decisions about how to perceptually engage and then to represent the music have an affect on the analytic result.

[18] For the second issue, that of “to whom” analytic observations apply, I revisit the issue of “cycles of twist” just considered. Hisama characterizes them as a “hidden dimension [that] subverts the dominant, traditional narrative [of climax].” (page 29) It would be possible to counter my concern with the aural referent of an analytic concept on the basis of this assertion. But, if we allow that this “hidden” model of structure does not require an aural presence, then the question arises for whom does it exist and how: does it exist for the analyst and her readers as a secret bit of knowledge? Or for the composer as a covert compositional technique? In other words, “to whom” does the analytic observation apply? At its root, this is a historical question: does the analysis apply to “us” in the present, to the “composer and her audience” in the past, or is there no temporal distinction? These issues of historical import apply generally to Hisama’s project. On one hand, each analytic chapter begins with a wealth of intriguing historical evidence about the biography of the composer and the circumstances of the work’s composition. Since this historical evidence “informs” the analyses, there is some reason to assume that analytic observations will be imbued with historical significance. But Hisama makes no such claims about the past; rather she states that her “argument is not based on compositional intention” and that her analytical study “enables a listener to experience new and compelling ways of understanding music.” (page 10) These statements about “intention” and “listening experience” locate the relevance of analytic observation in the present. If we assume that past and present are conflated in the project, this would amount to a claim that hearing is universal and that it cannot be shaped by new modes of thought. In other words, such an assumption would negate the point of Hisama’s project: to enable new modes of musical experience.

[19] The issues of “how” an analysis is formulated and “to whom” analytic observations are intended arise not only in Hisama’s GMM but in much scholarship seeking to show how music as a sounding phenomenon reflects and enacts the conditions of its production and reception. The problem of this correlation between sound design and social/intellectual context is most likely the dominant one for music scholarship in the new millennium. The questions that help to define the problem may be grouped around the issues of “how” or the analytic discourse and “to whom” or the historical reference. They are:

“How”

If the goal of an analysis is to make links between

musical design and composer biography and cultural context, then what kinds of

analytic discourse should be applied to establish this correlation? Can a

traditional discourse of technical creation and performative realization bear

the task of demonstrating how music reflects and enacts the conditions of its

creation and reception? Does the sign of the correlation between context and

design reside in the “surface” details which have perceptual immediacy or in the

“deep” structure which is manifest in some analytic modeling, e.g., a numerical

modeling?

“To Whom”

Does analytic interpretation make claims about the

conditions under which the composer worked? And if so, is analysis an attempt

to understand the creation of music in its historical context? If one analyzes

a work from the past, is analysis an attempt to replicate the historical

conditions of hearing and creating? Or can analysis only make statements about

how a listener/performer engages a piece of music in a performance in the

present?

[20] Hisama’s GMM is a distinguished example of scholarship that provides insight into the music and biographical circumstances of three important composers of musical modernism. Through Hisama’s work the historical significance of Crawford, Bauer, and Gideon has been clearly established as composers and as “women” who composed. Like other similar scholarship, it raises questions of “how” and “to whom”—that is, questions about the determinative role of analytic discourse on observation and the historical import of analytic statements. But most significantly, Hisama opens up new territory for music scholarship and offers analyses that indeed change the ways we hear Crawford’s, Bauer’s, and Gideon’s music through imaginative and insightful interpretations.

Judy Lochhead

Professor and Chair of Music

Department of Music

Stony Brook University

Stony Brook, New York 11794-5475

judith.lochhead@sunysb.edu

Footnotes

1. I

understand analysis and theory as sub-disciplines within the larger category of

musicology.

Return to text

2. In his New Grove article on analysis (with Anthony Pople),

Bent also shows the relation of analytic practice to “criticism” and

“aesthetics.” His restriction to theory and history here should not be read as a

repudiation of the earlier position but simply a narrowing for the purposes of

the series. See Ian Bent and Anthony Pople, “Analysis,” The New Grove

Dictionary of Music Online, ed. L. Macy (Accessed 2 June 2003),

http://www.grovemusic.com.

Return to text

3. I have left out some of the detail of Hisama’s argument

here, choosing instead to give a sense of her larger point.

Return to text

4. Hisama takes this term and concept from Elaine

Showalter: see her “Feminist Criticism in the Wilderness,” The New Feminist

Criticism: Essays on Women, Literature, and Theory, ed. Elaine Showalter

(New York: Pantheon Books, 1985): 243–70. Quoted in Hisama, page 19.

Return to text

5. Robert Morris, Composition with Pitch-Classes: A

Theory of Compositional Design (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1987) and

“New Directions in the Theory and Analysis of Musical Contour,” Music Theory

Spectrum 15/2 (1993), 205–208; Michael Friedmann, “A Methodology for the

Discussion of Contour: Its Application to Schoenberg’s Music,” Journal of

Music Theory 29/2 (1985), 223–48; and Elizabeth West Marvin and Paul A.

Laprade, “Relating Musical Contours: Extensions of a Theory for Contour,”

Journal of Music Theory 31/2 (1987), 225–67.

Return to text

6. Suzanne Cusick, “On a Lesbian Relation with Music: A

Serious Effort Not to Think Straight,” Queering the Pitch: The New Gay and

Lesbian Musicology, ed. Philip Brett, Gary C. Thomas and Elizabeth Wood (New

York: Routledge, 1994), 67–83.

Return to text

7. Mary

Poovey, A History of the Modern Fact: Problems of Knowledge in the Sciences

of Wealth and Society (Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press,

1998).

Return to text

8. Susan McClary, Feminine Endings: Music, Gender, and

Sexuality (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1991); Fred Everett

Maus, “Masculine Discourse in Music Theory,” Perspectives of New Music

31/2 (1993), 264–93; Cusick, “On a Lesbian Relation with Music” (note 6 above);

Joseph Kerman, “How We Got Into Analysis and How to Get Out,” Critical

Inquiry 7/2 (Winter 1980), 311–332; and Leo Treitler, “‘To Worship That

Celestial Sound’: Motives for Analysis,” Journal of Musicology 1/2 (April

1982): 153–70.

Return to text

9. I cannot fully develop the sense in which I use the term

presence. Simply stated, there must be some perceptual awareness of a phenomenon

that can be correlated with the concept. This does not mean that a model needs

to be perceived “as such” but only that it have a perceptual referent.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2003 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason, Managing Editor and Tahirih Motazedian, Editorial Assistant