Keynote Address, Twenty-seventh Annual SMT Conference in Seattle, WA, “Tragic Love and Musical Memory”

Robert Gauldin

Copyright © 2004 Society for Music Theory

[1] Before commencing this curious discourse on love, memory, and music, I would like to thank Jonathan Bernard and the SMT Program Committee for extending to me their kind invitation to address you today. I consider it a high honor and a distinct privilege.

[2] From Greco-Roman times to the present, the bodily organ associated with the seat of human affections has gradually risen, from the bowels through the liver and heart to eventually the brain. In replacing Freud’s divisions of the psyche (such as the Ego or Id), modern neurobiology has opted for a more somatic explanation of the mind by attempting to pinpoint various regions of the brain, their specific roles in governing human response, and the chemical transmitters through which they communicate. For instance, Eric Nestdler and Robert Malenka discuss the integration of some of these areas and how they forge connections in determining whether we deem an experience rewarding and whether we may wish to repeat it.(1) Although some students of human nature are dismayed by the omission of any reference to the “soul or spirit” in such purely physiological expositions, Antonio Damasio in his Descartes’ Error suggests that “Understanding the biological mechanisms behind emotion and feelings is perfectly compatible with a romantic view of their value to human beings.”(2) Even so, certain authorities in this field have admitted that their present models seem to work better when integrated with Freud’s psychological theories.(3)

[3] Whereas poets once rhapsodized over virile masculinity and maternal instincts, clinicians today speak of the hormones testosterone and estrogen. The ardor of our sexual desire is now gauged by milligrams of such neurotransmitters as dopamine, sometimes dubbed “the liquor of romance.” As Damasio points out, these chemical substances are “capable of forcing on us behaviors that we may or may not be unable to suppress by strong resolution.”(4) If the Tristan legend was updated to the present day, scientists would doubtless equate Brangäne’s love potion with vasopressin or oxytocin, hormones which not only facilitate attractions between the sexes but also induce bonding between mating partners.

[4] In their quest for a neurobiological theory of emotions, scientists are also forced to come to grips with the problem of memory. During his discussion of “Remembrances of Emotions Past,” Joseph LeDoux attempts to distinguish between implicit memory (or “emotional memories”) and explicit memory (or “memories of emotional situations”).(5) Since human love is capable of conveying such powerful affective sensations, some authors have incorporated them as the basis for their hypotheses in these areas. Helen Fisher, in her recent book Why We Love, has marveled at our brain’s capacity to retain and later recall with vivid detail and intense feeling specific romantic experiences from our past, or as she puts it, “we are uniquely endowed to remember him or her.”(6) Nor, as the recent movie “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind” proposes, can we wipe clean the slate of these recollections, either with the eraser of Dr. Mierzweiak’s machine or our own resolve.

[5] There is also the frequent association of particular past events with our sensory perception of those experiences, so that later on the effect of various stimuli on our five senses can induce an involuntary but powerful triggering of their memories. While in some cases this may only result in a more general

“memory of emotions,” in other instances such a stimulated recall can resemble an instantaneous photograph of a single moment frozen in time. For our purposes we will restrict our considerations of this phenomenon to former

romantic relationships and their possible sensory associations. Although

taste and touch are probably of secondary importance, certain foods and drink (perhaps pertaining to a particular candle-light dinner) or even tactile sensations (such as silken negligee or a rough tweed jacket) may unconsciously invoke these recollections. The recent research of Rachel Herz has expanded our understanding of the connection between memory and

odor, such as the lingering fragrance of “her perfume” or the pungent smell of

“his pipe tobacco.” In particular, Herz has convincingly demonstrated that emotional aspects of those recollections are rendered more potent in the presence of the fragrance itself. For Marcel Proust in his definitive novel on remembrance, memories were evoked by the aroma of a madeleine soaked in lime-blossom tea. The

visual associations we forge between particular places or things and the object of our affections can often produce especially poignant memories when we revisit or observe them later. No better illustration of these relationships exists than in Irving Kahal and Sammy Fain’s misty-eyed anthem to separation during World War II, where the sweetheart left behind laments that

“I’ll be seeing you in all of old familiar places

[6] Our primary interest lies in the last sensory domain—that of sound in general and music in particular. The accidental juxtaposition of a specific event in a romantic affair with the performance of a specific piece of music can produce a powerful though sometimes unintended bond between the two, frequently denoted by the colloquial expression “they’re playing our song.” Who can ever forget Illsa in the movie Casablanca cajoling Sam to “Play it once, for old time’s sake,” and the expression on Rick’s face when he again hears its haunting strains. Such referential associations (as Leonard Meyer is want to label them) between love and music can conjure up extremely poignant and evocative recollections, even among musicians who may pride themselves in their more objective approach to their art. Examples abound in dramatic works for the stage, as when the nostalgic strains of a half-forgotten waltz stir the memories of first love for both Marguerite in Gounod’s opera and Cinderella in Prokofiev’s ballet. (As a brief aside, you have doubtless already surmised that the “musical memory” we are discussing here differs from the bulk of related research found in such journals as Music and Perception.)

[7] The love of two people for one another has been celebrated in the creative efforts of various artists down through the ages. These works of art may originate concurrently with the romantic affair in question (such as Shakespeare’s later sonnets to the “dark lady,” probably his Jewish mistress at the time of their composition), or they may be originate some years later after the actual experience has been filtered through the artist’s memory banks (such as Hemingway’s recollections of his war wounds and encounter with a young nurse eventually gave rise to his novel A Farewell to Arms). Similar occurrences are legend in the area of musical composition, so that one wonders how many of the countless pieces written about love were the result of direct autobiographical experiences. The haunting memory of a beautiful lady has frequently cast its aura over musical masterpieces. For instance, Edward Elgar and William Walton’s Violin Concertos were heavily influenced by two different women, both of whom were named Alice. Although some composers doubtless preferred to keep such musical infatuations a private matter and therefore refrained from overtly advertising their relationships through dedications or programmatic prefaces, others consciously embedded either obvious or disguised clues pertaining to their romantic affections within the actual fabric of their music. These customarily took the form of “quasi-acronyms” equating letter names with pitch classes, either in melodic lines or vertical harmonies, although the use of associative keys may also be noted.

[8] Cogent examples abound in the music of Alban Berg. In the Opus 2 Songs, dedicated to his fiancee Helene Nahowsky, Berg takes great pains in the opening measures to establish both Helene’s D minor (a key he continually associated with her) and their composite acronym A

[9] The remainder of my talk will explore some tragic love affairs in the lives of three famous 19th-century composers and the manner in which memories of these amorous relationships were manifested in their artistic output. In our first case the romance and the musical composition it spawned were chronologically concurrent.

[10] Robert Schumann first met Ernestine von Fricken in June of 1834 when the eighteen-year old pianist came to Leipzig to study under Friedrich Wieck. The young composer had just concluded a romantic affair with Henriette Voigt, whom he had called his

“Eleonore” after Florestan’s

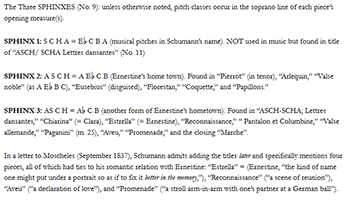

Example 2. Use of SPHINXES (= “acronyms”) related to the romantic relationship between Robert Schumann and Ernestine von Friken as found in his Carnaval (1834–35)

(click to enlarge)

[11] As early as his Op. 1 ABEGG variations, Schumann was fascinated with the idea of deriving musical pitches from the letters in names or words to serve as motivic bases for his themes, a practice that would continue through his compositional output; the

“coded messages” to Clara in his Davidsbünndlertänze are but one example.(9) (When discussing future instances of procedure, I will replace the more accurate expression

soggeto cavato, which has historical ties to the Renaissance, with the term

“acronym” as used in a general sense, despite the fact that it falls outside the specific definition of the word.) Although Schumann’s

Carnaval (1834–5) harbors several lingering echoes traceable back to his previous romance with Henriette—the identification of the author

“Florestan” in its original title and the

[12] In the light of his new romantic interest, Carnaval must have evoked poignant memories and to some degree even conflicting emotions for Schumann. He refrained from dedicating the cycle to Ernestine, despite the fact that it was obviously

“her piece.” Yet in playing it over later, he could not escape the lingering references to her which he had brazenly embedded in the music, since its melodic fabric was literally permeated with her two motives. Imagine his performing Clara’s little piece

“Chiarina,” knowing that its theme was based not on her name but rather on Ernestine’s

[13] Our next case history is quite different, for here any creative fallout from the romantic relationship in question did not manifest itself in the composer’s artistic works until some time after the affair was over.

[14] Tchaikovsky heard a thirty-three year old Belgian cabaret singer named Désirée Artôt perform during the season of 1868 in Moscow. Like Wagner’s youthful infatuation with the great soprano Wilhelmine Schröder-Deverient, he was probably more attracted to her consummate artistry and theatrical charisma than to her own personal charms. After arranging to see her privately on a number of occasions, he confided to his family that he “loved her very, very much” and intended to ask her hand in marriage. For whatever reason, the aspiring composer of twenty-seven never followed through, and soon afterward she eloped with a Spanish baritone. Although his personal correspondence chooses to make light of her rejection, I believe this aborted affair proved to be an emotional crisis from which Tchaikovsky never fully recovered.

Example 3. “Acronyms” for Petr Tchaikovsky and Désirée Artôt, as found in the tone poem Fatum (1868), the

(click to enlarge)

Example 4. The use of Balakirev’s suggested

(click to enlarge)

[15] In suggesting that her lingering aura was manifested through internal and less obvious means in his subsequent artistic output, David Brown has demonstrated the existence of

“acronyms” based on the couple’s names in certain works composed between 1868 and 1875. As

Example 3 illustrates, Tchaikovsky employed only one for himself (E C B A = scale degrees in the minor mode) but utilized several for Artôt, mostly prominently

[16]

Similar tonal relations occur in the Romeo and Juliet overture, whose original version (composed under Mily Balakirev’s guidance) was completed in 1869 soon after Désirée broke off their affair. While some scholars draw a parallel between Shakespeare’s star-crossed lovers and the composer’s earlier homosexual encounter with Vladimir Gerard or perhaps the unexpected suicide of Eduard Zak, I believe both external and internal evidence links the

“double theme” secondary key area of this work to his recent painful experiences with Artôt; consult

Example 4. In adhering to Balakirev’s penchant for keys with two sharps and/or five flats, during the exposition Tchaikovsky resolves the A7 prolongation (used to prepare the expected relative major shift from the tonic B minor to D major) as a German sixth to

Example 5a. Unusual features of Tchaikovsky’s

(click to enlarge)

Example 5b

(click to enlarge)

Example 5c

(click to enlarge)

Example 5d

(click to enlarge)

Example 5e

(click to enlarge)

Example 6. Background on Richard Wagner and Mathilde Wesondonk’s “affair of the heart.”

(click to enlarge)

Example 7. Music which Wagner probably associated with memories of his own romantic relationship with Mathilde Wesondonk, emphasizing the key of

(click to enlarge)

[17] Although the

[18]

Example 5a: Following the opening horn gesture (Tchaikovsky’s acronym) that opens the extensive introduction (an almost unheard-of procedure in a concerto), the music

immediately modulates to the relative major. Its broad lyrical theme (which never returns in the movement) contains obvious references to both his and diatonic versions of Artôt’s names linked together and set in Romeo and Juliet’s

“love key” of

[19]

Example 5c: Likewise, the first of the “double-themes” in the secondary area features these same acronyms, now incorporating Désirée’s specific pitches

[20]

Example 5e: The expansive cadenza, one of the most remarkable of the Romantic period, consists of three sections, each of which centers around Artôt’s theme and an ensuing development. The initial

[21] The second movement resembles an Albumblatt of faded vignettes, perhaps recalling those times the composer and singer shared together and appropriately set in

“their key” of

Example 5f–j (click to enlarge) | Example 5k–l (click to enlarge) |

[22] Aside from her mesmerizing stage presence, why did Désirée possess such a strong emotional appeal for Tchaikovsky? Since he would never actually experience sexual unity with her except in his fantasies, he might have continued to cling to the hope that she would have the perfect mate for him—the one woman who could redeem him from the guilt and depression of his homosexual inclinations. Although he saw her again some time later and admitted that she had “grown fat,” he still seemed unable to erase the haunting specter of their tragic relationship and what “might have been.” In fact, since so many of his later works feature the recurring motif of unrequited love (Hamlet, Francesca, Manfred, Swan Lake, Eugene Onegin, etc.), it would seem that only in fairy tales (The Sleeping Beauty) did the couple in question live “happily ever after.” Even as late as Op. 65, he was still dedicating songs to her.(17)

[23] My final case in point is more complex. It represents a multi-tiered hierarchy, in which original music begot from the composer’s romance was in turn incorporated into a new dramatic work of art whose plot not only paralleled the original relationship but also exhibited three separate yet distinctive instances of memory recall. I am referring, of course, to the infamous affair of the heart between Richard Wagner and Mathilde, the youthful and charming wife of Otto Wesendonk, one of his generous patrons. In addition to providing a chronological outline of their association, Example 6 highlights the crisis of their romance in item 3, which occurred during Wagner’s work on the poem and drafts for the first two acts of Tristan und Isolde while he and his wife Minna resided at a cottage Asyl on the Wesondonk estate.

[24] Since pitch acronyms are not characteristic of Wagner’s compositional technique, we must look elsewhere for possible clues tying his music to Mathilde. The most fruitful line of inquiry would seem to lie in the realm of associative tonality, an increasingly significant technique in the tonal process of his later music dramas. It is my personal conviction that the composer consciously linked the memories of his and Mathilde’s romantic relationship with the key of

[25] We will examine three scenes in Tristan where musical memory plays a significant role.(20) In each case the circumstances and method of recall vary considerably. But before proceeding further, we must first question our justification for even using the term “musical” memory here. For as Edward Cone has conjectured , do the characters in opera really “hear” the music swirling around them? In our case one short phrase from the poem’s text may hold the answer. Immediately before Tristan’s entry in Act II, string tremolos underscore the impatient Isolde as she extinguishes the torch used to guide her lover. Near the end of Act III as she finally arrives and approaches the feverish and now blind Tristan, he staggers toward her and cries out “What, do I hear the light, the torch?” For although he can no longer see the flame, Wagner makes sure we realize that his hero is hearing those same tremolos derived from the earlier scene.(21) I believe the composer assumes a similar stance throughout the opera—that the lovers are completely aware of the music accompanying their actions and emotions—for it is necessary that he lay down a repository of definitive motifs and passages to serve as a “memory bank” from which to draw for their later recollections.

Example 8. Motifs and passages which accompany Tristan and Isolde’s initial “glance“ (after drinking the “love potion” near the end of Act I) and their subsequent illicit “night of love” (in Act II)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[26] Two significant portions of Tristan establish those emotional experiences that in turn provide the foundation for musical memories recalled later in the opera. Both are indelibly linked to the composer’s romance with Mathilde at Aysl. The opening of the Prelude up to the D minor harmony in measure 21 (shown in reduction under the POTION/GLANCE complex in Example 8), anticipates its expanded climactic restatement near the close of Act I, where the lovers’ communal drinking of the Death/Love Potion first stirs the flames of passion within them and sets into motion the unfolding events that will culminate in their eventual demise. This passage subsequently functions as a tonally invariant ritornello, recurring at four crucial dramatic moments during the remainder of the work, three of which are directly related to memory recall. The second “memory bank” section encompasses the entire love duet complex in Scene 2 of Act II, which significantly opens with material drawn from Mathilde’s Träume and closes with the working out of the SONG OF DEATH motif, possibly derived from the initial gesture of her Album Sonate. The remainder of Example 8 lists the principal themes employed in the last half of this lengthy scene; only the DEATH and BLISS motifs have appeared earlier.

Example 9. Motivic and tonal summary of the Love Duet complex in Act II, Scene 2 of Tristan und Isolde, which will furnish the basis for the subsequent “recollection of memories” sections during the following scene and in Act III

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[27] As shown in Example 9, the structure of the Act II love duets is divisible into three large sections, labeled LOVE DUETS I, II, and III. Prior to the final duet’s shift to B major, the first pair is framed and largely controlled by Mathilde’s key of

Example 10. Tristan’s reply to Marke (Act II, Scene 3) represents the first group of memory recollections

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

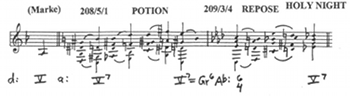

[28] The first memory recall occurs after Marke’s lengthy D-minor monologue, when he questions Tristan as to the cause and source of his infidelity (Example 10). Although in the ensuing LINK the knight refuses to divulge its origin, an orchestral restatement of the POTION music (drawn from the Prelude and the end of Act I) makes it clear that his hidden thoughts are returning to the crucial moment when he and Isolde first partook of that magical elixir. Its concluding E7 harmony functions as an enharmonic augmented sixth in reestablishing the

Example 11. Tristan’s vague and imprecise recollections of Isolde and their “night of love” as he awakes from his sick bed (Act III, Scene 1), and the distorted rhythmic settings of the Duet motifs as he feverishly awaits Isolde’s arrival and entry (Scene 2)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[29] The first two scenes of Act III provide several different compositional approaches to the recollection of musical memories. When the sick Tristan attempts to make his first coherent reply to Kurvenal (Example 11), he commences with the opening gesture of his strophic aria, discussed in Example 10. As his memories turn toward Isolde, the gloomy clouds of F minor gradually dissipate in favor of his single ray of hope, symbolized by the music of the Act II love duets and set in Mathilde’s relative key of

[30] Tristan’s further confused remembrances at the opening of Scene 2 result in additional motivic deformations. His wild agitation and feverish gestures while staggering from his sick bed in anticipation of Isolde’s arrival testify as to his confused state of mind, so that his fragmented recollections of motifs associated with the Act II duet music are now rhythmically distorted in changing and asymmetrical meters (middle of Example 11).(25) As the exhausted hero finally falls into her arms, the POTION passage wells up for one last time, but its following GLANCE portion only succeeds in reaching C major before a half-diminished chord denotes his demise.(26)

[31]

While Wagner allows Brangäne, Melot, Kurvenal, and Marke tie up the loose ends of the drama during Scene 3, Isolde remains stoic and silent beside the fallen Tristan, lost in thought and retreating into her own inner world. As she repeatedly strives to recall in her mind’s ear the music associated with their night of love, so does the initial gesture of the SONG OF DEATH motif successively attempt to seek out its original tonal environment—first in F, then

Example 12. Isolde’s literal recollections of the Love Duet music (Act II, Scene 2) during her concluding Transfiguration (Act III, Scene 3)

(click to enlarge)

[32] It seems only natural that Wagner would recapitulate part of the Act II duet music to support Isolde’s recollections in her Transfiguration. In its final version the two passages he selected (the SONG OF DEATH portion of the second

Example 13. A comparison of the formal components and tonal schemes in Wagner’s Final Version of Isolde’s Transfiguration (= almost literal restatement of the B-major Love Duet in Act II) with his Preliminary Draft of the Transfiguration (late discarded)

(click to enlarge)

[33] An examination of Wagner’s Preliminary Draft nevertheless appears to contradict this seemingly effortless reprise by documenting the composer’s

struggles in attempting to reconcile his new text with his old music. Not only does a two-measure insertion occur within the initial

[34] Nor is this the end of our story, for the Mathilde/Isolde aura, as exemplified by the key of

[35] In Meistersinger this new attitude is manifested in the two scenes that prominently feature Sachs (= Richard) and Eva (= Mathilde), both of which open with a change of key into

[36] Suffice to say, the Tristan progression and its association with Wagner/Tristan and Mathilde/Isolde was subsequently purloined by later composers and employed in their works as a personal cipher to denote their

own romantic relations and memories. In addition to the disguised versions relating to Helene found in Berg’s first two opus numbers and the blatant quotation in his

Lyric Suite pertaining to Hanna Fuchs, instances occur in such far ranging pieces as the Richard Strauss

[37] So what lessons, if any, may we extract from this prolonged discourse? Perhaps as scholars of music, we should heed the moral from the tale of the blind men examining the elephant: to wit, the consideration of works of art from a broader perspective—one in which the correlation of both external and internal viewpoints and evidence results in a more holistic synthesis. Therefore, as musicologists we should occasionally divert our focus from purely historical, social, or biographical issues in order to dirty our hands in an intensive scrutiny of the actual music, the analysis of which may yield vital clues linking the artist with his or her creation. On the other hand, as theorists we should occasionally vacate our sometimes sanitized laboratories of compositional modeling in search of features that may link prominent structural characteristics of a works to the composer’s personal life or interests. Of course, I do not mean to imply that such connections exist between every individual piece and its creator. But that should not deter us from searching for them. In the latest issue of Intégral I was struck by how many of the essays in the forum “Music Theory at the Turn of the Millennium” stress the need for closer ties not only between the musical disciplines but other allied scholarly areas as well. And what more appropriate environment to commence such communal endeavors than these joint conventions involving both of our disciplines. For how many times have we heard our fellow colleagues on either “side of the fence” extol the virtues of attending historical and theoretical sessions to our mutual benefit. May our collaboration long continue.

[38] Although I realize I may be guilty of setting a precedent, I would nevertheless like to conclude with a brief dedication: to all of those whose romantic relationships to all of us have awakened such rich and enduring memories of past experiences, both joyful and painful, and have forged associative bonding to pieces of music in ways we never thought possible, so that now we perceive those works of art in a different and more highly personal manner.

Robert Gauldin

Eastman School of Music

RGauldin@esm.rochester.edu

Footnotes

1. Eric Nestler and Robert Malenka, “The Addicted Brain,”

Scientific American 290/3 (March 2004): 81–82.

Return to text

2. Antonio Demasio, Descartes’ Error: Emotion, Reason, and the Brain (New York: G.P. Putman’s Sons, 1994), 164.

Return to text

3. See Mark Solms, “Freud Returns,” Scientific American 290.5 (May 2004), 82.

Return to text

4. Demasio, op. cit. 121.

Return to text

5. Joseph LeDoux, The Emotional Brain: The Mysterious Underpinnings of Emotional Life

(New York: Touchstone Books, 1996), 179–224.

Return to text

6. Helen Fisher, Why We Love: The Nature and Chemistry

of Romantic Love (New York: Henry Holt, 2004), 149. She cites several

examples on page 192, involving George Washington and the Chinese poet Su Ting-Po.

Return to text

7. Irving Kahal and Sammy Fain, “I’ll Be Seeing You” from Right This Way (New York: The New Irving Kahal Music Company and Fain Music Co., 1938).

Return to text

8. Robert Gauldin, “Reference and Association in the Vier Lieder Op. 2

of Alban Berg,” Music Theory Spectrum 21/1 (Spring 1999): 32–42. The score of the third song appears on 153 of the spring issue of

Spectrum 26/1, although no mention is made of the associative rationale for the modulation to D minor.

Return to text

9. See Larry Todd, “On Quotations in Schumann’s Music”

in

Schumann and his World, edited by Larry Todd, (Princeton: Princeton

University Press, 1944).

Return to text

10. Clara’s acronymn CHAA, based on “CHiArinA,” appears as

the initial theme of Schumann’s Piano Concerto in A minor.

Return to text

11. I am indebted to Amy Sze’s lecture recital “The

Realization of Schumann’s Philosophical Ideals and Personal Fantasies in

Carnaval Op. 9” (Eastman School of Music, April 2004) for calling my

attention to certain background information on Schumann and Ernestine.

Return to text

12. David Brown, Tchaikovsky: A Biographical and Critical Study. Vol. 1:

The Early Years. (London: Victor Gollancz, 1978), 197–98. Tchaikovsky

employed the German rather than the Russian alphabet, as witnessed by the “Des”

=

Return to text

13. Ibid, 198–200.

Return to text

14. This material is extracted from my paper entitled

“Tchaikovsky and Désirée: A Possible Secret Program for the

Return to text

15. This theme opens the development section and concludes

with the pitches

Return to text

16. The initial solo flute theme outlines a diatonic form

of Artôt’s acronym (

Return to text

17. Tchaikovsky continued to cultivate the principal of a

“double” secondary theme complex (stemming from Romeo and Juliet) in most

of his major works, including the last three symphonies. However, in the initial

movement of the “Pathétique,” his final work in that genre, the second idea is

curiously missing in the recapitulation. In addition, the B minor tonic and

parallel major ending strongly suggest ties back to Romeo.

Return to text

18. This material is based on my paper “Tracing Mathilde’s

Return to text

19. See Robert Gauldin, “Wagner’s Parody Technique: ‘Träume’

and the Tristan Love Duet.” Music Theory Spectrum 1 (1979), 35–42.

Return to text

20. Important analytical studies of this opera include

Alfred Lorenz, Das Geheimnis der Form bei Richard Wagner. Vol. 2: Der

musikalische Aufbau von Richard Wagners ‘Tristan und Isolde.’ (Berlin,

1926); Robert Bailey, “The Genesis of ‘Tristan und Isolde,’ and a Study of

Wagner’s Sketches and Drafts for the First Act.” (PhD disseration, Princeton

University, 1969); and Roger North, Wagner’s Most Subtle Art: An Analytical

Study of ‘Tristan und Isolde.’ (London: Robert North [Book Factory], 1996).

Return to text

21. These two passages may be found on pages 128 (Act II)

and 278 (Act III) of the Schirmer vocal score.

Return to text

22. Thomas Grey, Wagner’s Musical Prose: Texts and

Contexts (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 122.

Return to text

23. This strophic aria and the music preceding it may be

found on pages 208–212 of the Schirmer vocal score.

Return to text

24. This passage begins on page 228 and eventually concludes

at the bottom of 234 (in

Return to text

25. Consult pages 273–78 of the Schirmer vocal score.

Return to text

26. See bottom of page 276 to 277 in the Schirmer vocal

score.

Return to text

27. These occur at 2/2/291 (F major), 1/2/292 (

Return to text

28. A condensed score of the Draft and additional

commentary may be found in Robert Bailey’s Richard Wagner: Prelude and

Transfiguration from ‘Tristan and Isolde.’ Norton Critical Score Series.

(New York: W. W. Norton, 1985), 103–52.

Return to text

29. Robert Gauldin, “Isolde’s Transfiguration and Wagner’s

Second Thoughts,” paper delivered at the International Symposium on 19th Century

Music in Nottingham, England 1996.

Return to text

30. See pages 460–61 of the Dover edition full score of

Tannhäuser.

Return to text

31. See especially the passage associated with the “kiss”

(page 184 in the Schirmer vocal score), although the section abounds with

“Tristan-chords,” most of which are spelled as half-diminished sevenths on F (or

if you will, an

Return to text

32. John Warrack, “The Sources and Genesis of the Text” in

Richard Wagner: Die Meistersinger von Nurnberg. Cambridge Opera Handbooks.

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), 11.

Return to text

33. See pages 218–26 in the Schirmer vocal score.

Return to text

34. This scene commences on page 433 of the Schirmer vocal

score and proceeds to the Tristan quotation found on page 452.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2004 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason, Managing Editor and Rebecca Flore and Tahirih Motazedian, Editorial Assistants