Response to Janet Schmalfeldt’s Response

Daphne Leong and Elizabeth McNutt

REFERENCE: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.05.11.1/mto.05.11.1.schmalfeldt.php

Copyright © 2005 Society for Music Theory

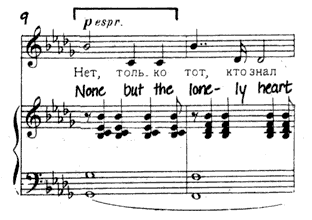

Example 4b. Tchaikovsky, “None but the Lonely Heart”

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 4a. Surface rhythm, notated meter, and time-point structure, mm. 1–10

(click to enlarge and listen)

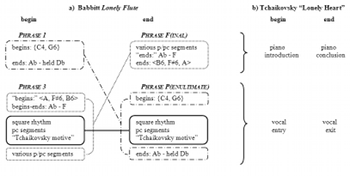

[1] In the spirit of Janet’s “whimsical” hearing of Babbitt’s Lonely Flute “as a naughtily overdetermined parody of Tchaikovsky’s song, with Tchaikovsky’s music itself representing the antipode of Babbitt’s aesthetic, though not necessarily his sympathies” (paragraph 12), we demonstrate two additional connections between Babbitt’s Lonely Flute and Tchaikovsky’s “Lonely Heart.”

[2] Babbitt unmistakably underlines pc

[3] Compare this to Lonely Flute, which opens (Example 4a)

with a phrase bounded by C4–

[4] As shown in

Example

10a, the end of the work (measure 158) restates a held

Example 10. Opening and closing of Lonely Flute (* indicates anomaly in array-lyne reference; _ indicates pitch identity) (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 11 (click to enlarge and listen) |

[5]

Flutter tongues (F.T.) perform a function similar to that of the changing

dynamics above. Lonely Flute contains only four instances of flutter tongue. Two

of these occur in close proximity near the end of the work (just preceding the

fast “riff”), both on relatively long

[6]

C–

[7]

These various emphases on

[8]

Although clear analytically, the prominence of

Prelude/Postlude

[9]

The end of Lonely Flute ties in to the beginning not only through emphases on

[10]

A comparison of Examples

10a and 4a shows that the penultimate phrase

(measures 155–158) echoes phrases 1 and 3 (measures 1–3, 7–9). Like phrase 3, the

penultimate phrase sticks out because of its square rhythms and possible motivic

references to Tchaikovsky’s “Lonely Heart.” Like phrase 1, it begins with a leap

between G6 and C4, and ends with the held

[11] In addition, Examples 10b and 10c show that the peak pitch(class)es at the opening of phrase 3 <A, F#6, B6> conclude the work, in reverse order and in retrograde pitch contour. The final phrase shown in Example 10c also references phrase 3 in other ways that we do not detail here.

[12] Example 12a diagrams these relationships between opening phrases 1 and 3 and

closing phrases P and F (penultimate and final). Phrases 3 and P relate strongly

(rhythm, motive, p/pc strings), with weaker links between the begin/endpoints of

phrases 1 and P, and of phrases F and 3, respectively. The symmetry thus

displayed, and the musical characteristics of the four phrases, suggest a

hearing of the work that corresponds roughly to the Tchaikovsky song model

(Example 12b): piano introduction preceding vocal entry, brief piano postlude

following vocal cadence. In other words, phrases 1–2 of Lonely Flute introduce

phrase 3 ff., and phrase F concludes following phrase P. Lonely Flute’s opening

emphasis on {

[13] That Babbitt drew such specific opening-closing relationships, in both pitch and rhythm, from distant portions of pc and tp arrays again attests to his compositional agility. The option of interpreting these opening and closing passages as prelude and postlude, in parallel to Lonely Flute’s namesake, suggests further dimensions of parody.

Daphne Leong

University of Colorado at Boulder

College of Music, 301 UCB

Boulder, CO 80309–0301

Daphne.Leong@colorado.edu

Elizabeth McNutt

University of Colorado at Boulder

College of Music, 301 UCB

Boulder, CO 80309–0301

elizabeth.mcnutt@colorado.edu

Footnotes

1. This passage follows on the heels of

the “riff,” which also references a row statement.

Return to text

2. The only other “special effect” of the work, key clicks

(marked + in the score), also perform a specific structural function. Key clicks

mark portions of row segments that occur “early” or “late” at block boundaries,

i.e., that begin in the previous block, or end in the following block. Only one

key click of the five instances in the work does not perform this function: the

key click in measure 98 (Example 5 [DjVu]

[GIF]), which sets up the p/pp tp aggregate and the

work's climax, occurs not on the high

Return to text

3. Babbitt appears to have relaxed strict relations between

phrase 3 and the referenced array lyne in order to obtain rhythm and pc

correspondences to the penultimate phrase.

Return to text

4. The relative lengths of the hypothesized prelude

(Phrases 1–2, 18 quarter notes) and postlude (5 quarter notes) very roughly

match the proportions of the Tchaikovsky introduction and postlude (32 and 8

quarter notes).

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2005 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason, Managing Editor and Rebecca Flore, Editorial Assistant