Contextual Drama in Bach *

James William Sobaskie

KEYWORDS: Bach, Schenker, Schoenberg, Babbitt, Problem, Grundgestalt

ABSTRACT: Some tonal compositions impart impressions of purely musical drama not readily revealed by Schenkerian analysis alone. Arnold Schoenberg’s concept of musical problem, a component of his notion of musical idea, may aid in illuminating the contextual relations responsible for such dramatic effects within a Schenkerian view. This essay applies the Schoenbergian concept of musical problem within a Schenkerian approach to Bach’s St. Matthew Passion chorale Ich bin’s, ich sollte büßen and Bach’s G-sharp minor Prelude from the Well-Tempered Clavier, Vol. I.

Copyright © 2006 Society for Music Theory

[1] Purely musical drama often intrigues, drawing us back again and again.* Much drama arises from tonal relations that elicit expectations subtly manipulated and subsequently fulfilled, relations readily revealed by Schenkerian analysis. However, contextual processes may elicit expectations of their own, producing allusive effects that contribute to a work’s fascination. Formed from ordered sequences of evocative events existing within the tonal fabric, these successions of separate but similar moments are unique to the composition in which they sound and present a narrative that complements the unfolding of the tonic triad. Such processes gradually reveal their goals as they unfold, and thus are dynamic, progressive systems of organization.(1) Let us begin with a most familiar musical example.

Example 1. J. S. Bach, St. Matthew Passion: Ich bin’s, ich sollte büßen, with analytical overlay

(click to enlarge and listen)

[2] More than two decades ago, Milton Babbitt gave a series of six presentations at the University of Wisconsin that were later chronicled in the book, Words About Music: The Madison Lectures.(2) In a lecture largely devoted to tonal music, Babbitt addressed Bach’s St. Matthew Passion chorale Ich bin’s, ich sollte büßen (BWV 244, No. 16), as well as Schenker’s famous analyses of the work.(3) What interested Babbitt most about Bach’s music on that occasion was a contextual process that unfolded over the course of the chorale, a sequence of distinctive pitch events not emphasized by Schenker’s sketches. Example 1 reproduces Bach’s vocal score, augmented by overlay, to illustrate the subsequent review of Babbitt’s comments. Audio Example 1 offers a rendition of the entire chorale.

[3] The contextual process Babbitt identified in Ich bin’s, ich sollte büßen

proceeds from the first phrase’s most striking contrapuntal event, which is

readily perceptible in Audio Example 2

(mm. 1–2). That event, of course, is the

suspension on the downbeat of the second measure, heard in the soprano and alto

voices and linked to the word "büßen."(4) Babbitt explained to his youthful audience:

“It’s quite obvious that

[4] While we cannot know for sure, Bach’s inspiration for this salient harmonic event may have been the concluding notes of the traditional melody’s first phrase, which exhibit the same sequence of scale degrees, ˆ4 to ˆ3. Yet the sharp dissonance formed by their juxtaposition in Bach’s suspension at the start of the bar does not fail to impress, and places

[5] Reinforcement of the

[6] To the cross relations that Babbitt identified, we might add the

[7] In the second half of the chorale (mm. 6–12), which ingeniously reharmonizes the soprano melody of the first half, the elongated semitonal step of

[8] Other pitch events provide further reinforcement of the semitonal pairing. For instance, the suspension figure on the downbeat of m. 10, involving the superimposition of

Example 2. Ich bin’s, ich sollte büßen: voice leading summaries of mm. 1-2 and mm. 11-12

(click to enlarge and listen)

[9] The cumulative implication of such conspicuous semitones, Babbitt would suggest, was that some overt resolution of the conflict between the pitch classes of

[10] Babbitt argued that Bach deliberately avoided a conventional cadential six-four sonority at the end of Ich bin’s, ich sollte büßen in favor of a setting that stated scale degrees ˆ4 and ˆ3, originally expressed by

[11] Remarkably, the contextual process Babbitt described coordinates with the climax and conclusion of the chorale’s essential tonal process: the descent of the fundamental line and its final cadence. Example 3

offers a transcription of Schenker’s sketch of Ich bin’s, ich sollte büßen from Free Composition.(11) While

the C5 represents an accented passing tone over the subdominant harmony, it

reasserts the primary tone of the composition in a dynamic way in preparation

for the conclusion of the chorale, as Schenker’s sketch shows. Indeed, within

the brief span of the work, it is not hard to hear the rich

Schoenberg’s concept of “musical problem”

[12] Although Milton Babbitt did not characterize the contextual process he identified in Bach’s Ich bin’s, ich sollte büßen as the presentation and pursuit of a purely musical problem, it may be understood in those terms. And while I was not immediately aware of the source of his interpretation when I heard Babbitt speak, it now seems clear that his inspiration must have been the thought and work of Arnold Schoenberg.

[13] Schoenberg’s concept of “musical problem” appears in many places in the composer’s writings. Among the most revealing references are these:

“Musical ideas are such combinations of tones, rhythms, and harmonies that require a treatment like the main theses of a philosophical subject. It [the musical idea] raises a question, puts up a problem, which in the course of the piece has to be answered, resolved, carried through. It has to be carried through many contradictory situations, it has to be developed by drawing consequences from what it postulates, it has to be checked in many cases and all this might lead to a conclusion, a pronunciamento.”(12)

"The furtherance of the musical idea

. . . may ensue only if the unrest—problem—present in the Grundgestalt or in the motive (and formulated by the theme or not, if none has been stated) is shown in all its consequences.”(13)Every succession of tones produces unrest, conflict, problems

. . . Every musical form can be considered as an attempt to treat this unrest either by halting or limiting it, or by solving the problem.(14)

[14] Simply put, Schoenberg suggested that a musical idea, by nature, embodies some sort of conflict. Such an idea, which Schoenberg regarded generally as a unified combination of tones, durations, and harmonies, and sometimes also referred to as a Grundgestalt, or basic shape, expresses a musical “problem” that demands a contextually-satisfactory “solution.”(15) For Schoenberg, a musical idea is a brief, yet distinctive entity, often a component of a theme. Its problem, in turn, represents a truly “motivic” force, one that would seem to stimulate a corresponding response within the unfolding music. The solution of the problem forms the basis for the purely musical drama we perceive within the context of a composition.

[15] Adopting this perspective, we might consider the first melodic phrase of the traditional chorale melody Bach set in Ich bin’s, ich sollte büßen as a

“musical idea” of sorts, since it forms part of the basic substance on which the piece was founded. The striking contrapuntal combination

[16] Schoenberg’s concept of musical problem has been invoked frequently in recent years. Many authors, particularly those inspired by Patricia Carpenter, have undertaken the analysis of “tonal” problems—those involving challenges to the primary tonality of a work—within the framework of Schoenberg’s harmonic theories.(16) However, Schoenberg’s references to his concept, particularly those quoted above, suggest he believed that musical problems may take numerous forms, not just the tonal.(17) For instance, Ich bin’s, ich sollte büßen manifests a conflict between two non-tonic scale degrees. One may imagine musical problems involving meter and rhythm, as well as other domains. And of course, the musical problems embodied and explored by Schoenberg’s serial works do not involve competing keys at all.

[17] Recognition that musical problems may involve more than just conflict among tonalities enables much wider analytical application of the construct. And perhaps not surprisingly, Schoenberg’s concepts of musical idea and musical problem may complement a Schenkerian approach, as David Epstein has shown.(18) While some of us may be loathe to abandon the comfort and protection of theoretical dogmatism, a relaxed stance may lead to otherwise elusive insight. To illustrate, I should like to turn to another brief work of Bach.

Bach’s Prelude in G-sharp Minor

Example 4. J.S. Bach, Well-Tempered Clavier, Vol. I: Prelude in G-sharp minor

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 5. Prelude in G-sharp minor: the “musical idea” and its “problem”

(click to enlarge and listen)

[18] The eighteenth prelude from the first volume of the Well-Tempered Clavier (BWV 863) may not be as famous as some of its companions, but it deserves similar renown and respect. Example 4 provides a copy of its score. Audio Example 4 offers a presentation of the entire prelude.

[19] While we may be inclined to consider the distinctive upper melody of the Prelude’s first measure as its basic thematic material, I would propose that the real “musical idea” of the work, in the Schoenbergian sense, consists of the contrapuntal complex shown in Example 5. Audio Example 5 illustrates the span shown in Example 5. As these graphic and audio examples illustrate, the engaging treble melody and its simpler accompanying bass combine to express an expanding aural shape that soon contracts.

[20] The “problem” of the musical idea shown in Example 5 decisively emerges at its point of greatest expansion, and is distinguished by the contextual clash between the lowered submediant

scale degree, expressed by E5, and the leading-tone scale degree,

expressed by

[21] In effect, the voice leading that follows the contextually dissonant

juxtaposition of

[22] Schoenberg once declared: “Whatever happens in a piece of music is nothing but the endless reshaping of a basic shape.”(20) From this perspective, Bach’s G-sharp minor Prelude may be heard as a simulation of problem solving in which the components of its musical idea seem to be explored by separation, recombination, and transformation in order to elicit what appears to be a convincing “solution” to its internal voice leading “problem.” The drama in this metaphor parallels human problem solving behavior, which may involve disassembly, trial-and-error experimentation, and extrapolation, before a “flash-of-insight&qrduo; brings forth a solution and closure. To be sure, no actual problem solving takes place here—the Prelude should not be taken as a literal record of Bach’s wrestling with a recalcitrant pair of pitch classes. Instead, the music presents a sequence of aural events we may liken to the familiar experience of solving a problem. Bach’s Prelude enables us to vicariously experience, within the realm of sound, an exploratory process of reaching satisfactory closure.

[23] For instance, the score in Example 4 shows that the Prelude’s musical idea, most readily distinguished by its melodic “theme,” reappears in mm. 2–3. There, its components are transformed by transposition and the principles of invertible counterpoint to produce a new shape that contracts, bringing the “problematic” components closer to form an augmented ninth. Its next two statements, in mm. 5–7, expose the now-familiar theme at new pitch levels, and even more strikingly, in a major modality, though without the bass’s neighbor figure and the contextually dissonant harmonic “problem.”

[24] Similar exploration of the musical idea’s potential may be perceived in the first two-thirds of the Prelude. In all, sixteen recognizable instances of the idea sound. Ten transformations arise from transposition and occasional modal change, as the solid brackets beneath the systems of Example 4 reveal. Five other transformations proceed from the processes of inversion and transposition, plus occasional modal change, as the dotted brackets beneath the systems show. In the relatively few measures without a complete expression of the Prelude’s basic musical idea, motivic components proliferate, perhaps simulating the activity of creative “play” that often characterizes problem solving.

[25] The “problematic” relationship represented by the contextual dissonance E5 and

[26] Problem-solving simulation may be perceived through m. 18, leading to the longest passage of the Prelude in which no complete statement of its basic musical idea or obvious expression of its conflict occurs. Following such systematic and intensive exploration of the thematic basis of the Prelude, this apparent “void” cannot help but elicit wonder. Measure 25, at the conclusion of that span, surely represents a climax, as the portrayal of mm. 24–27 in Audio Example 7 reveals.

Example 6. G-sharp minor Prelude: “problem” and “climax“ voice leading summaries of mm. 1-2 and mm. 25-26

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 7. Prelude in G-sharp minor: comprehensive voice-leading sketch

(click to enlarge)

Example 8. Prelude in G-sharp minor: rhythmic reduction of the bass, mm. 15-25

(click to enlarge and listen)

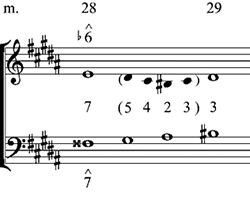

Example 9. J.S. Bach, Well-Tempered Clavier, Vol. I: G-sharp minor Prelude: mm. 26-29

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 10. G-sharp minor Prelude: voice leading summary of the problem’s “solution” in mm. 28-29

(click to enlarge and listen)

[27] At that very point, the constituents of the Prelude’s “musical problem” sound at the widest degree of registral separation yet heard, and for the very first time, on a downbeat. Prominently projected, they would seem to communicate a dramatic culmination, a dénouement. The pitch E5, following a flourish, resolves to

[28] As the comprehensive sketch of the Prelude shown in Example 7 suggests, the climactic event of m. 25 immediately precedes and seems to prompt the descent of the fundamental line. There, the “problematic” E5 heard in mm. 24–25 assumes its tonal role as the upper neighbor of the primary tone. Its arrival, and that of the fundamental line’s descent, is heralded by a remarkable rhythmic phenomenon. Example 8 reveals that a grand linear span in the bass, essentially a descending minor sixth extended and expanded by registral shifts, unfolds in mm. 15–25. Quietly obtaining attention by relatively even values at the outset, the descending bass span decelerates midway, before it systematically accelerates toward the climax in m. 25. Audio Example 8 illustrates this engrossing rhythmic process. The accelerative nature of this passage has the effect of drawing close attention to mm. 25–26, lending an unmistakably dynamic quality to this span of the music. Reversing and expanding the minor sixth span traced by the Prelude’s theme, it highlights E5’s opposing degree,

[29] The end of the Prelude presents its “problem’s” “solution” and concludes its contextual process. Example 9 reproduces those final measures,

while Audio

Example 9 demonstrates. As these illustrations reveal, the ending includes a bow toward the subdominant and a plagal cadence, tonal gestures common to many of Bach’s codas. It also includes a Picardy third at the conclusion. A glance at Example 9 reveals that this closing passage presents transposed and inverted transformations of the familiar melodic theme from the Prelude’s musical idea that have not yet been heard before. The first of these expresses the

“problematic” dyad E4–

[30] The principles of melodic and contrapuntal inversion, prominently

invoked throughout the Prelude, both figure in its “problem’s” “solution,” as do

the original “problematic” pitch classes of E and

Contextual Processes in Bach

[31] The culmination of the G-sharp minor Prelude’s “problem-solving” process coordinates with the composition’s tonal drama and depends on the work’s voice leading fabric for its expression. Yet the narrative’s sequence of events effectively remains separate, operating in its own domain and perceived on a different plane. Its conclusion coincides with the achievement of ultimate musical closure, two measures after the fundamental line has run its course. Offering its own form of dramatic flux, born of a purely musical conflict and gradually emerging hints of resolution in the musical fabric, the contextual process of the G-sharp minor Prelude lends unmistakable animation and dynamism to Bach’s brief work and confers its own unifying effects. Surely it contributes to the music’s seductiveness, as well as its art. Here within Bach’s G-sharp minor Prelude, as in his St. Matthew Passion chorale, Ich bin’s, ich sollte büßen, the dramatic contextual process assures rewarding rehearings.

James William Sobaskie

Department of Music

Hofstra University

Hempstead, New York 11549

musjws@hofstra.edu

Works Cited

Babbitt, Milton. 1987. Words About Music: The Madison Lectures, ed. Stephen Dembski and Joseph N. Straus. University of Wisconsin Press.

Burkhart, Charles. 1978. “Schenker’s Motivic Parallelisms.” Journal of Music Theory 22: 145–175.

Carpenter, Patricia. 1983. “Grundgestalt as Tonal Function.” Music Theory Spectrum 5: 15–38.

—————. 1997. “Tonality: A Conflict of Forces.” In Music Theory in Concept and Practice, ed. James Baker, David Beach, and Jonathan Bernard, 97–129. University of Rochester Press.

—————. 2005. “Schoenberg’s Tonal Body.” Theory and Practice 30: 35–68.

Cone, Edward T. “Schubert’s Promissory Note: An Exercise in Musical Hermeneutics.” Nineteenth-Century Music. 5 (3): 236.

Dineen, Murray. 2001. “Schoenberg’s Logic and Motor: Harmony and Motive in the Capriccio No. 1 of the Fantasien Op. 116 by Johannes Brahms.” Gamut 10: 3–28.

—————. 2005a. “The Tonal Problem as a Method of Analysis.” Theory and Practice 30: 69–96.

—————. 2005b. “Tonal Problem, Carpenter Narrative, and Carpenter Motive in Schubert’s Impromptu, Op. 90, No. 3.” Theory and Practice 30: 97–120.

Epstein, David. 1979. Beyond Orpheus: Studies in Musical Structure. MIT Press.

Neff, Severine. 1993. “Schoenberg and Goethe: Organicism and Analysis.” In Music Theory and the Exploration of the Past, ed. Christopher Hatch and David W. Bernstein, 409–433. University of Chicago Press.

Schenker, Heinrich. [1933] 1969. Five Graphic Music Analyses. Dover.

—————. [1935] 1979. Free Composition. Longman.

Schoenberg, Arnold. 1967. Fundamentals of Musical Composition, ed. Gerald Strang. Faber.

—————. 1969. Structural Functions of Harmony, ed. Leonard Stein. Norton.

—————. 1975a. “Linear Counterpoint.” In Style and Idea: Selected Writings of Arnold Schoenberg, ed. Leonard Stein, trans. Leo Black. University of California Press.

—————. 1975b. “My Evolution.” In Style and Idea. University of California Press.

—————. 1995. The Musical Idea, and the Logic, Art, and Technique of its Presentation, ed. Patricia Carpenter and Severine Neff, 395–396. Columbia University Press.

Sobaskie, James William. 2003a. “The Emergence of Gabriel Fauré’s Late Musical Style and Technique.” Jounral of Musicological Research 22 (3): 223–75.

Sobaskie, James William. 2003b. “Tonal Implication and the Gestural Dialectic in Schubert’s A Minor Quartet.” In Schubert the Progressive: History, Performance, Practice, Analysis, ed. Brian Newbould, 53–79. Ashgate Publishing Limited.

—————. 2005. “The ‘Problem’ of Schubert’s String Quintet.” In Nineteenth-Century Music Review 2 (1): 57–92.

Footnotes

* This essay was read at the annual meeting of the Music Theory Society of New York State held on 8 April 2006 at Skidmore College in Saratoga Springs, New York. I thank the Legacy of Bach session chair Reed Hoyt, fellow presenters Joel Lester and Edward Klorman, and program chair Chandler Carter, for their encouragement and advice.

Return to text

1. The later music of Gabriel Fauré (1845–1924), while

remaining essentially tonal, often departs from traditional practice, drawing

upon contextual processes for reasons of structural integrity and expressive

intent. For instances, see my essay, Sobaskie 2003a,

especially its discussions of several of the composer’s mélodies, including

Le

don silencieux (1906; see pp. 244–254), Roses ardentes (1908; see pp. 265–268),

and Dans un parfum de roses blanches (1909; see pp. 268–273). In Le don silencieux,

for instance, the interval of the fifth serves as a melodic frame

for vocal activity in each of the mélodie’s six sections, its space gradually

rising and becoming more chromatic, thus promoting a systematic brightening of

vocal timbre. The vocal part of Roses ardentes reveals a process of progressive

range expansion in which melodic motion, initially centered on the pitch B4 in

the manner of a reciting tone, gradually expands around that point, both

registrally and chromatically, until it reaches the octave E4/E5 by the end.

Finally, the vocal part of Dans un parfum de roses blanches exhibits the

phenomenon of chromatic completion, reserving the last of the yet unheard pitch

classes for the most dramatic point of the mélodie.

Return to text

2. Babbitt 1987 I was a student at the University of Wisconsin during Milton Babbitt’s residency in the fall of 1983 and recognized, as did my peers, that Babbitt’s unparalleled understanding of the twentieth century’s two greatest theorists enabled unprecedented insights.

Return to text

3. Babbitt 1987, 137–143. This passage comes from Chapter Five,

“Professional Theorists and Their Influence.” The well-known analyses Babbitt

referred to during his presentation are those in Schenker 1969, 32–33.

Return to text

4. Bach’s association of the striking dissonance

Return to text

5. Babbitt 1987, 139.

Return to text

6. Babbitt 1987, 140. Babbitt’s employment of the word

“parallelism” should not be confused with the Schenkerian notion of “motivic parallelism,” which involves the expression of the same melodic pattern at different levels of tonal structure within a composition. Babbitt’s usage corresponds to what many of us would describe as the varied repetition of a melodic motive at the musical surface. For more on the Schenkerian concept, see Charles Burkhart’s classic article, Burkhart 1978, 145–175. Today, many analysts prefer the term

“expansion,” instead of “motivic parallelism,” when describing instances of

motivic repetition at higher levels of structure.

Return to text

7. In conversation, Mary Arlin drew my attention to a most

remarkable attribute of this chorale from Bach’s St. Matthew Passion.

Despite the vivid imagery and profound despair of the text (“It is I, I should

atone, my hands and feet bound, in Hell. The scourges and the fetters and what

You endured, my soul deserves.” [my translation]), all six of the cadences in

Ich bin’s, ich sollte büßen conclude with major triads. The choir, expressing humanity’s recognition of its role and responsibility in Christ’s crucifixion, nevertheless alludes to the

St. Matthew Passion’s fundamental message of hope.

Return to text

8. Babbitt 1987, 141–143.

Return to text

9. Heinrich Schenker offers an account of this major-major

seventh harmony in his coordinated sketches of

Ich bin’s, ich sollte büßen in Schenker 1969, 32–33, as well as a verbal explanation and example in Schenker 1979, 65 and Fig. 62, No. 12.

Return to text

10. Babbitt 1987, 139.

Return to text

11. Schenker 1979, Fig. 22a (measure numbers added). I present this version of Schenker’s

view of

Ich bin’s, ich sollte büßen here, rather than one of those in

Five Graphic Music Analyses, simply because of its concision.

Return to text

12. Arnold Schoenberg, “Beauty and Logic in Music,” an unpublished essay preserved at the Arnold Schönberg Center in Vienna. I thank Eike Feß, archivist at the Schönberg Center, for sharing with me a digital facsimile of the document, whose catalogue number there is T 67.02. A partial transcription of this essay appears in Schoenberg 1995, 395–396.

Return to text

13. Schoenberg 1995, 226–227.

Return to text

14. Schoenberg 1969, 102.

Return to text

15. For instances of Schoenberg’s use of the term Grundgestalt, see Schoenberg 1969, 193–194, and Schoenberg 1975b, 91, as well as that cited above. (It may be of interest to MTO readers that an audio recording of Schoenberg delivering his

“My Evolution” lecture at UCLA in 1949 is available at the website of the Arnold Schönberg Center; see

http://www.schoenberg.at/6_archiv/voice/voice29.htm to hear this remarkable historical document.) Regrettably, Schoenberg never offered a precise and detailed definition for his concept of

Grundgestalt. Patricia Carpenter explored the idea using Schoenberg’s harmonic theories in her article, Carpenter 1983, 15–38. However, the best illumination of its implications may be found in Schoenberg 1995.

Return to text

16. For discussions of “tonal” musical problems presented within the framework of Schoenberg’s harmonic theories, see: Neff 1993, 409–433; Schoenberg 1995, 395-396; Carpenter 1997, 97–129; Dineen 2001, 3–28; Carpenter_2005 35–68; Dineen 2005a 69–96; and Dineen 2005b, 97–120.

Return to text

17. For instance, see my essay, Sobaskie 2005, 57–92, which reveals a comprehensive contextual process that simulates the impression of musical problem solving and spans all four movements of the composer’s final chamber work. In that masterpiece, a dissonant harmony featured in the very first phrase but not conventionally resolved—a diminished seventh chord that collapses back on the tonic harmony—represents the crux of a musical problem whose determined pursuit appears to end with a voice leading solution that emerges in the closing bars of the finale. Schubert’s String Quartet in A minor also features a comprehensive contextual process, one in which opposing melodic gestures heard at the start of the first movement seem to converse and contend until the end of the last, when a climactic synthesis achieves reconciliation and resolution of their conflict. See my chapter, Sobaskie 2003b, 53–79. Taken together, these works of Schubert, as well as those by Fauré mentioned in footnote 1 and those by Bach under scrutiny in this essay, demonstrate that contextual processes may take many different forms, only some of which are readily illuminable by Schoenberg’s concept of musical problem.

Return to text

18. Any admixture of Schenkerian and Schoenbergian analysis proceeds from the work of David Epstein; see Epstein 1979. Milton Babbitt, with whom Epstein studied, provided the

Forward to that pioneering book.

Return to text

19. Cone 1982, 236.

Return to text

20. Schoenberg 1975a, 290. Following the statement quoted above, Schoenberg offers two metaphors—one from the world of childhood and another from the realm of cinema—that are particularly appropriate to and illuminative of the way in which the basic musical idea of the G-sharp minor Prelude is treated. Schoenberg declares:

“I say that a piece of music is a picture-book consisting of a series of shapes, for which all their variety still (a) always cohere with one another, (b) are presented as variations (in keeping with the idea) of a basic shape, the various characters and forms arising from the fact that variation is carried out in a number of different ways; the method of presentation used can either ‘unfold’ or ‘develop’. . . In the course of the piece, the new shapes born of redeployment (varied forms of the new theme), new ways for its elements to sound) are unfolded, rather as a film is unrolled. And the way the pictures follow each other (like the

‘cutting’ in a film) produces the ‘form.’” Schoenberg 1975a, 290. It would seem abundantly clear from these metaphors, as well as a consideration of Bach’s music, that Arnold Schoenberg’s notion of

Grundgestalt was profoundly influenced in its development by models provided by the preludes and fugues of the

Well-Tempered Clavier.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2006 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason, Managing Editor and Andrew Eason, Editorial Assistant