Structural and Transformational Properties of All-Interval Tetrachords

Adrian P. Childs

KEYWORDS: all-interval tetrachords, complement-union pairs, common-tone relationships, transformational systems, partitions, Elliott Carter

ABSTRACT: An analysis (from Guy Capuzzo’s 1999 dissertation) of Elliott Carter’s Scrivo in Vento for solo flute serves as a point of departure for the consideration of certain properties of all-interval tetrachords (AITs). First, the roles of the individual (and a priori distinct) dyads are examined in light of the complement-union pair property exhibited by AITs. Second, a systematic means of describing common-tone relationships among AITs is proposed and studied. Examples from two works by Carter (Shard and Scrivo in Vento) show the flexibility and usefulness of the system.

Copyright © 2006 Society for Music Theory

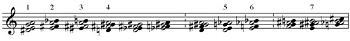

[1] Figure 1 shows an analysis, taken from Guy Capuzzo’s 1999 dissertation, of a passage (mm. 37–42) from Elliott Carter’s Scrivo in Vento for solo flute.(1) The figure is organized to highlight all-interval tetrachords (AITs) that occur within the passage, dividing each tetrachord into component dyads of interval class (ic) 3 (on the top staff) and ic6 (on the bottom).(2) This division reflects the fact that any non-overlapping combination of an ic3 dyad with an ic6 dyad will result in an AIT. The AIT set classes are thus what Robert Morris calls complement union pairs (CUP2); and the musical reduction of Figure 1 manifests a path through a compositional space defined by the complement union property (CUP).(3)

[2] In this particular example, Capuzzo is interested in the fact that adjacent AITs often share their ic3 or ic6 dyads (the brackets underneath the figure highlight these common-tone pairs), a feature that is reflected clearly on the musical surface by repetition and register. He suggests that the common tones be heard as “pivots,” and that “thinking of the passage as ‘moving’ through the CUP AIT spaces captures the rhapsodic character of the passage somewhat better than does an analysis that relies solely on [twelve-tone operators], which reflects less clearly the held pitches that typify the passage.”(4)

[3] A closer look at the reduction, however, reveals that every pair of adjacent AITs exhibits at least two common tones. In the instances not bracketed by Capuzzo, the common tones do not form an ic3 or ic6 dyad: the common tones between chords 1 and 2 form ic5; between chords 5 and 6, ic4. Additionally, the final pair of chords exhibits three common tones, with

[4] Decoupling consideration of common tones between AITs from the lens of CUP spaces (and the necessary emphasis that this places on ic3 and ic6 dyads) reveals that all component dyads of an AIT can participate in common-tone retention. This observation suggests two questions that will frame the remainder of this paper:

- What structural role do other dyads (i.e., those not participating in the CUP space) play with respect to AITs? and

- How might common tones among AITs be described and explored more systematically?

I.

[5] An AIT implies a partition on the set of interval classes, dividing its six members into three pairs (or partition components), each defined by virtue of being non-overlapping in the AIT. AITs with prime form [0137] partition the interval classes as 1+4, 2+5, and 3+6; [0146]-type AITs partition as 1+2, 4+5, and 3+6 (see Figure 3). Significantly, the CUP2 characteristic of AITs is reflected in the fact that ic3 and ic6 always appear in the same partition component, since they are always non-overlapping in any given AIT.

[6] The need for ic3 and ic6 to appear in the same partition component is easily proved. Because the partition components are defined by virtue of non-intersection, interval-class dyads appearing in different partition components therefore share one common tone. If ic3 and ic6 were to be in different partition components, they would share one common tone; and the dyad formed by the other two tones would be a member of ic3. Since an AIT has exactly one representative of each interval class, this duplication of ic3 is not permissible. Thus, ic3 and ic6 must be in the same partition component.(6)

[7] Similar reasoning also establishes that interval classes that sum to 6 cannot appear in the same partition component. If, for example, ic1 and ic5 were to appear in the same component, then the ic1 and ic6 dyads would have a common tone (by virtue of appearing in different partition components). However, the non-common tones would form another ic5 dyad, independent from the one occupying the same component as the ic1 dyad. Again, an AIT can have only one of each interval class, so the pairing of ic1 and ic5 in the same partition component is not permissible. The pairing of ic2 and ic4 is ruled out by the same method. These two limitations regarding the structure of partitions implied by AITs are sufficient to reduce the 15 possible pairwise partitions of the six interval classes to the two associated with [0137] and [0146] that are demonstrated in Figure 3.(7)

[8] Four unordered triples of ics—(1,3,5), (1,5,6), (2,3,4), and (2,4,6)—always appear in distinct partition components in both of the permissible partitions. Two of these triples—(1,5,6) and (2,4,6)—relate respectively to the [016] and [026] trichords that are subsets of both [0137] and [0146]. Their complementary partners—(2,3,4) and (1,3,5), respectively—describe the dyads formed between the fourth note and each member of the trichord subset. Other unordered triples can be formed from the ics appearing in distinct partition components for one of the partitions. Again, these describe either a trichord subset ([013] and [037] for [0137], and their M transforms [025] and [014] for [0146]) or the intervals between the fourth note and each member of a trichord subset.

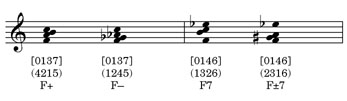

[9] The distributions of interval classes described by these partitions and sets of unordered triples create a preponderance of trichord subsets that contain or imply tertian harmonies ([025], [026], [037]) or suggest overlapping thirds ([014]). This explains in part the potential for AITs to be heard as quasi-tonal sonorities, particularly when distributed to emphasize these subsets. Figure 4 shows the four qualities of AIT and their associated set class (Tn/In-type) and interval normal form (equivalent to Tn-type) labels, along with a suggested “tonal” label. [0137]-type AITs are labeled + (major) and - (minor), according to the [037] consonant triad embedded within. [0146]-type AITs are labeled as seventh chords, reflecting the distribution that results from placing the ic2 dyad on the outside as a minor seventh. Those with interval normal form (1326) are labeled simply 7, since the modal quality of the seventh chord is made ambiguous by the lack of a third. Their inversions, with interval normal form (2316), are labeled ±7, since the modal quality of the third is simultaneously major and minor. These labels will be used throughout this paper to simplify descriptions of AITs.(8)

Figure 5. Transformational labels for multiple-common-tone relationships among AITs

(click to enlarge)

Figure 6. Examples of transformations performed on F7

(click to enlarge)

[10] Given any AIT, there are 18 other AITs that share at least two common tones with it. Figure 5 demonstrates a contextual labeling system for the transformational relationships that obtain between AITs with at least one dyad in common. In the figure, the initial sonorities are AITs of each quality with a “root” of F (shown to the left of the double bar in each system). The other AITs that share at least two common tones with each initial AIT are shown as the results of the transformations that appear above them. Common tones are highlighted with open noteheads.

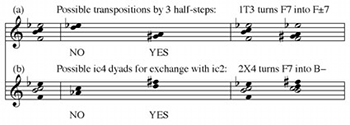

[11] Most transformations can be described using the language of partial transposition: two tones remain fixed (trivially, they are transposed by zero half-steps), while the other two are transposed by some other amount.(9) These moves are labeled

nTm, where n is the ic of the moving dyad and m is the ic describing the transposition.(10) Since ic3 and ic6 must be in the same partition component, the other dyads (ics 1, 2, 4, and 5) can all be transposed by ic 3 (either T3 or T9) to produce another AIT. The direction of transposition is uniquely determined in each case by the requirement that the final result also be an AIT.(12) Since the dyad being moved shares one common tone with the ic3 dyad (by virtue of being in a different partition component), transposition by 3 half-steps in one direction will move that common tone onto the other note in the ic3 dyad, resulting in only a trichord. The desired transformation is achieved by transposition in the other direction. Figure 6a demonstrates the application of the 1T3 transformation to the F7 AIT. Transposing the ic1 dyad {B, C} by T3 results in {D,

[12] The special roles of ic3 and ic6 flowing from the CUP2 structure of AITs permit these dyads to be transposed by any value, so long as overlap with the fixed dyad is avoided. Transposition by any of the six ics is possible for the ic3 dyad. For transposition by 1, 2, 4, or 5 half-steps, motion in one direction will create a common tone with the fixed dyad, while motion in the other direction will have the desired outcome of a new AIT. Transposition by 6 half-steps has only one result, so direction is not a concern. Transposition by 3 half-steps yields a special scenario, since it creates an AIT in either direction. The transformations are distinguished by appending + or - to the 3T3 label: + corresponds to T3; -, to T9. These moves also result in three common tones (rather than two), since one member of the ic3 dyad will remain unchanged under the transposition. Due to its transpositional symmetry, the ic6 dyad can only be transposed by 1, 2, or 3 half-steps: transposition by 4 or 5 is equivalent to 2 or 1, respectively; and transposition by 6 results in no change. With the exception of the two 3T3 transformations (which are each other’s inverses), all partial transpositions in this system are involutions.(12)

[13] A few additional transformations occur by exchanging one interval class with another. These are labeled

nXm, indicating that icn is exchanged for icm. These transformations represent a change in the partitioning scheme of the initial and final AITs. The dyad exchange takes place around a fixed axis of pitch-class inversion, which holds both the icn dyad of the original AIT and the icm dyad of the resultant AIT invariant. Again, the final product is uniquely determined simply by requiring that the result be an AIT. Figure 6b demonstrates the application of the 2X4 transformation to the F7 AIT. The axis of inversion that holds the ic2 dyad {E![]() , F} invariant is described by I8 (passing through E and B

, F} invariant is described by I8 (passing through E and B![]() ). The ic4 dyads that share this axis of inversion are {A

). The ic4 dyads that share this axis of inversion are {A![]() , C} and

{D, F

, C} and

{D, F![]() }. Since the first of these creates a common tone with the fixed {B, C} dyad, the exchange of {E

}. Since the first of these creates a common tone with the fixed {B, C} dyad, the exchange of {E![]() ,

F} with {D, F

,

F} with {D, F![]() } will produce the desired result: a B- AIT. Like the 3T3 transformations, the exchange operations are not involutions: nXm and

mXn form inverse pairs.

} will produce the desired result: a B- AIT. Like the 3T3 transformations, the exchange operations are not involutions: nXm and

mXn form inverse pairs.

Figure 7. Reduction of Carter: Scrivo in Vento (mm. 37–42)

(click to enlarge)

Figure 8. Excerpt from Carter: Shard (mm. 56–57)

(click to enlarge)

Figure 9. Excerpt from Carter: Shard (mm. 48–50)

(click to enlarge)

Figure 10. Reduction of Carter: Scrivo in Vento (mm. 1–17, 21–36)

(click to enlarge)

Figure 11. Excerpt from Carter: Scrivo in Vento (mm. 63–66)

(click to enlarge)

[14] Figure 5 is laid out to highlight certain features of the complete transformational system. Barlines segregate the resultant chords by set class and quality. Chords on the upper staff in each system are members of the same octatonic collection as the initial sonority, while those on the lower staff lie in other octatonic collections. Given any AIT, 12 of the other 15 AITs contained within the same octatonic collection will share at least two common tones with the original chord. (Of the other three, two share one common tone, and one is the octatonic complement.)

[15] As an example, Figure 7 reproduces the reduction from mm. 37–42 of Carter’s Scrivo in Vento that appeared in Figure 2, with chord and transformational labels added. The use of a contextual labeling system highlights certain similarities among common-tone relationships that would be obscured by the use of Tn/In/M operators. For example, the three occurrences of 4T3 would be I1, I11, and I3, respectively.

III.

[16] Carter’s treatment of common-tone-related AITs seems to favor maximum variety in the vocabulary of transformations, sometimes modulated by their CUP2 characteristic.(13) Figures 8 and 9 show passages from Shard for solo guitar that illustrate this trend. The excerpt in Figure 8 (with sequential AITs marked with brackets) exhibits systematic alternation of non-overlapping ic3 and ic6 dyads, which produce AITs by virtue of CUP. Of the ten transformations that can navigate the CUP compositional space (those that begin with either 3 or 6), six occur in this passage, with only one duplication. Figure 9 shows a passage that is not limited to common tones associated with the ic3 and ic6 dyads. The patterning of overlapping AITs (again demarcated by brackets) is much less consistent, and adjacent chords occasionally exhibit only one common tone (in which case no transformational label is provided).(14) Again, the transformational labels exhibit maximum variety, with only one duplication.

[17] The musical materials of Scrivo in Vento generally exhibit strong contrasts of pacing, register, and dynamics. The passage modeled by Figures 1, 2, and 7 is fast, low, and soft (with occasional loud, high-register outbursts that are omitted from the reduction), and demonstrates a significant level of transformational variety, although there are more duplications than were found in the excerpts from Shard. The opening section of the piece is also low and soft, but consists of slow notes connected together in long, lyrical lines. Figure 10 provides AIT-based reductions of this material from the opening and also of a later passage that returns to the same character (though in a slightly higher register). Unlike the previous examples, these passages exhibit a much narrower transformational vocabulary. The moving dyad is almost always ic3, and only three of the seven transformations marked by this dyad are employed. Of particular note is the succession 3T3- followed by 3T2, which seems to provide closure for both segments (in both cases a fast figure, omitted from the reduction and symbolized by the dotted barline, immediately precedes the final two chords, further distinguishing them as a closing unit in this texture).

[18] The first half of the piece culminates with an extended fast passage that bridges the earlier contrasts of dynamics and register by moving from high and loud to low and soft.(15) This section, which is given in Figure 11 along with analysis of its component AITs, also synthesizes transformational vocabularies. Like the second excerpt from Shard (Figure 9), the patterning of AITs is irregular, and neighboring chords sometimes have only one common tone. The overall collection of transformations exhibits a high level of variety, although there is some repetition as was seen in mm. 37–42 (Figure 7). Reflective of the opening materials, however, the beginning and ending of this passage exhibit particular emphasis on operations that move ic3 (and, more generally, on those that can navigate a CUP space through manipulation of ic3 or ic6). Both stretches of CUP-related transformations end with inversional pairs: the opening segment closes with twin involutional 3T1s, and the entire excerpt ends with 3T3- (recall its association with closure in Figure 10) and 3T3+.(16)

[19] The proposed system of contextual transformational labels provides a complete, yet succinct, vocabulary for the description of multiple-common-tone relationships among AITs. Brief examination of excerpts from the music of Elliott Carter shows resonance with one of the composer’s primary aesthetics: the exploitation of maximal variety within the context of a single larger unifying concept. Future explorations could consider group structures implied by subsets of the system, especially those focusing on involutions or on maintenance of octatonic collections.(17)

Adrian P. Childs

University of Georgia

Hugh Hodgson School of Music

250 River Road

Athens, GA 30602-7287

apchilds@uga.edu

Works Cited

Bernard, Jonathan W. 1993. “Problems of Pitch Structure in Elliott Carter’s First and Second String Quartets.” Journal of Music Theory 37 (2): 231–66.

Capuzzo, Guy. 1999. “Variety within Unity: Expressive Means and Their Technical Ends in the Music of Elliott Carter, 1983–1994.” Ph.D., University of Rochester.

Harvey, David I. H. 1989. The Later Music of Elliott Carter: A Study in Music Theory and Analysis. Garland Publishing.

Koivisto, Tiina. “Aspects of Motion in Elliott Carter’s Second String Quartet.” Intégral 10: 19–52.

Lewin, David. 1987. Generalized Musical Intervals and Transformations. Yale University Press.

—————. 1993. Musical Form and Transformation: Four Analytical Essays. Yale University Press.

McCartin, Brian J. 1998. “Prelude to Musical Geometry.” College Mathematics Journal 29 (5): 354–70.

Morris, Robert. “Pitch-Class Complementation and its Generalizations.” Journal of Music Theory 34 (2): 175–246.

O’Donnell, Shaugn. 1998. “Klumpenhouwer Networks, Isography, and the Molecular Metaphor.” Intégral 12: 53–80.

Schiff, David. 1998. The Music of Elliott Carter. Cornell University Press.

Straus, Joseph N. 2003. “Uniformity, Balance, and Smoothness in Atonal Voice Leading.” Music Theory Spectrum 25 (2): 305–52.

Footnotes

1. Capuzzo 1999, 317 (Ex. 4.12). The notes on the upper

staff of chord 6 are erroneously given as

Return to text

2. The term “all-interval tetrachord” is defined in this

paper as referring to any of the 48 pitch-class sets that are members of the M-

and Z-related set classes represented by prime forms [0137] and [0146].

Return to text

3. Capuzzo 1999, 134 (n. 100), 141. CUP and CUP2 are drawn from Morris 1990.

Return to text

4. Capuzzo 1999, 142–43. The “CUP AIT spaces” are defined by

Capuzzo as compositional spaces whose objects—ic3 and ic6 dyads—are connected if

they have no pitch classes in common. Compositional spaces, including examples

pertaining to AITs, are defined in Morris 1990. Similar

networks with an explicitly analytical (rather than compositional) motivation

are found in Lewin 1998.

Return to text

5. Enharmonic respellings are liberally employed in Figure

2 (and other reductions in this paper) to avoid augmented unisons. Dotted

barlines in the reduction indicate intervening musical material that has been

omitted from the reduction. The final chord of this reduction includes a

high-register

Return to text

6. A slightly different reasoning with the same result: The

overlapping of an ic3 and ic6 dyad to produce one common tone will create an

[036] trichord, which, by virtue of containing two ic3 dyads, cannot be a subset

of an AIT.

Return to text

7. A very different proof of the uniqueness of the two set

classes of AITs, focusing on the sequential intervals formed by AITs modeled on

pitch-class wheels, is provided in McCartin 1998.

Return to text

8. Without loss of generality or specificity, these “tonal”

labels can be transformed into non-tonal labels of the form Lx, such as those

used by Lewin in his analysis of Stockhausen’s Klavierstück III (Lewin 1998, 16–67). In this system, L is a letter representing the set

class (with upper- and lower-case letters distinguishing inversionally-related

Tn-types) and x is an integer (mod 12) representing the transposition level from

a designated canonical form (which is labeled with x=0). + and - would be

replaced with one upper- and lower-case letter, and 7 and ±7 would be replaced

by another. Pitch-class letter names designating chord “roots” would be replaced

by values of x. (I am grateful to an anonymous reviewer for drawing this

affinity to my attention.)

Return to text

9. On partial transposition, see: O‘Donnell 1998 and Straus 2003.

Return to text

10. It is important to note that m is an interval class (an

unordered pitch-class interval) rather than an ordered pitch-class interval (as

is traditionally used in the labeling of transposition operations). This

distinction is highlighted by the demonstrations associated with Figure 6 below.

Return to text

11. In every case but one (described in paragraph 12

below), one possible interpretation of partial transposition by ic m will result

in an AIT, while the other will not (and is thus discarded; see Figure 6). This

limitation in the definition of nTm permits these labels to adhere to the strict

definition of transformation proposed by David Lewin. It also renders the

transformations injective (one-to-one). As they are also surjective (onto) over

the set of 48 AITs, these transformations are thus also operations. See Lewin 1987, 3.

Return to text

12. Half of the partial transpositions—1T3, 2T3, 3T1, 3T5,

4T3, 5T3, and 6T1—can also be defined as contextual inversions, inverting the

AIT across an axis that will hold the fixed dyad invariant.

Return to text

13. The use of AITs in Carter’s music has been highlighted by other scholars, though

without any particular focus on common tones. See: Bernard 1993; Harvey 1989; Koivisto 1996; Schiff 1998.

Return to text

14. AITs related by one common tone can be modeled by

compound operations. The move from

Return to text

15. Capuzzo 1999, 308 (Ex. 4.2) delineates the two-part form of

the piece.

Return to text

16. Again focusing on navigation through CUP spaces,

Capuzzo’s analysis of this passage captures those AITs that relate by

transformations starting with 3 or 6. See 149–50, 321–22 (Exx. 4.18 and 4.19).

Return to text

17. Preliminary versions of this article were presented at annual meetings of the

Southeast Section of the American Mathematical Society and Music Theory

Southeast. For their helpful comments on earlier drafts of this article, I wish

to thank John Turci-Escobar, Michael Buchler, and an anonymous

reviewer.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2006 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason, Managing Editor and Andrew Eason, Editorial Assistant