The Efficacy of K-Nets in Perlean Theory

Gretchen C. Foley

REFERENCE: ../mto.07.13.2/mto.07.13.2.buchler.php

Copyright © 2007 Society for Music Theory

[1] This response addresses two topics in Michael Buchler’s article “Reconsidering Klumpenhouwer Networks,” namely relational abundance and the issue of hierarchy and recursion. In the abstract preceding his essay Buchler states that “K-nets also enable us to relate sets and networks that are neither transpositionally nor inversionally equivalent, but this is another double-edged sword: as nice as it is to associate similar sets that are not simple canonical transforms of one another, the manner in which K-nets accomplish this arguably lifts the lid off a Pandora’s Box of relational permissiveness.” I will confine my remarks to K-nets and their applicability to George Perle’s compositional theory of twelve-tone tonality. In so doing, I hope to demonstrate that not only are K-nets “nice” to use in associating similar sets, they are highly efficient tools in a Perlean context.

K-nets and Cyclic Sets

Figure 1. Cyclic set 2,9 generated by alternating inversionally related interval cycles 7 and 5

(click to enlarge)

[2] In order to establish the efficacy of K-nets in Perlean theory, we must first define cyclic sets, arrays, and axis-dyad chords. A cyclic set combines two inversionally related interval cycles, such as interval 7 and interval 5. When the members of the two cycles are placed in alternation, every pair of alternating pcs shows a consistent difference, representing the formative interval cycle. In Figure 1 the pcs in open noteheads show the cyclic interval 7, and the alternating pcs in closed noteheads show the inversionally related cycle 5. Additionally, every pair of adjacent pcs forms a sum. Three adjacent pcs form two so-called tonic sums, which repeat throughout the cyclic set. In Figure 1 the three bracketed pcs 0-2-7 yield the tonic sums 2 and 9, which repeat with every trichordal segment. The second bracketed pcs 9-5-4 also sum to 2 and 9. The recurring pair of tonic sums provides the cyclic set its name; the cyclic set in Figure 1 is thus identified as 2,9. Finally, the difference between the tonic sums provides the underlying interval cycle (9-2=7).

[3] The trichordal segments in Figure 1 belong to two different set classes, 3-9 (027) and 3-4 (015). As such, they are neither transpositionally nor inversionally equivalent. Yet a declaration of non-equivalence seems counterintuitive, since both sets derive from the same symmetrical cyclic set and thus share the same internal structure. The K-nets in Figure 2a clearly display this relationship. These networks are strongly isographic; that is, they have identical arrow configurations and associated T and I transformations. Moreover, all trichords in the 2,9 cyclic set are strongly isographic since they arise from the same source, the 2,9 cyclic set. Any three adjacent pcs from this set can be fitted into the nodes of the more abstract K-graph in Figure 2b. This K-graph efficiently displays the recursion inherent in the 2,9 cyclic set.

|

Figure 2a. Strongly isographic K-nets of trichordal segments of cyclic set 2,9 (click to enlarge) |

Figure 2b. K-graph of any trichordal segment of cyclic set 2,9 (click to enlarge) |

Figure 3. Cyclic set 0,7 generated by rotating cyclic set 2,9

(click to enlarge)

Figure 4. Positively isographic K-graphs of trichordal segments of Perle cycles 2,9 and 0,7

(click to enlarge)

Figure 5a. Array 2,9/0,7, formed from cyclic sets 2,9 and 0,7

(click to enlarge)

Figure 5b. K-net of array 2,9/0,7(TS = tonic sum)

(click to enlarge)

Figure 6. K-graph of all axis-dyad chords from even rotations of the cyclic sets in array 2,9/0,7

(click to enlarge)

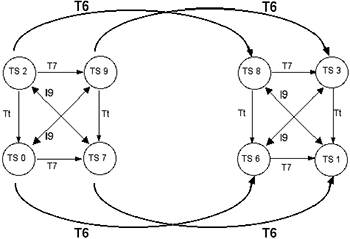

Figure 7a. T6 relationship between two arrays represented in K-nets

(click to enlarge)

Figure 7b. K-graph of all transpositions of array 2,9/0,7

(click to enlarge)

Figure 8a. I2 relationship between two arrays represented in K-nets

(click to enlarge)

Figure 8b. K-graph of all inversions of array 2,9/0,7

(click to enlarge)

[4] A different alignment of the ascending and descending interval 7 cycles from Figure 1 produces a new pair of repeating tonic sums, as shown in the 0,7 cyclic set of Figure 3. Although all trichordal segments within this cyclic set will be strongly isographic, they will not share this relationship with trichordal segments from the 2,9 cyclic set of Figure 1. Instead, the bracketed segments drawn from the two cyclic sets are positively isographic; that is, they share identical T-values between corresponding nodes but a consistent difference between their I-values, as shown in Figure 4. In these two K-graphs the identical T-values represent the interval 7 cycle underlying both cyclic sets, while the difference of ten (t) in both of their corresponding I-values represents the difference between the tonic sums in the two cyclic sets. This difference results from rotating the upper interval cycle ten times clockwise (or two times counter-clockwise) from the original alignment in Figure 1, and is expressed as <Tt>.

[5] Buchler opines that “If two trichords

K-nets, Arrays, and Axis-dyad Chords

[6] Any two cyclic sets in a vertical alignment create an array, which takes its name from the combined cyclic sets. Figure 5a shows the array 2,9/0,7 formed from the cyclic sets discussed above, with the array’s corresponding K-net in Figure 5b. Just as the interval cycles within a cyclic set may rotate in relation to one another, the cyclic sets within the larger array may also rotate, creating a variety of alignments. The K-net in Figure 5b demonstrates the types of relationships among tonic sums. The linear pairs comprise the tonic sums of the cyclic sets. The vertical pairs represent relationships between the tonic sums of the cyclic sets in a difference alignment (wherein cycles of like aspect, ascending or descending, are aligned). The diagonal pairs show relationships between the tonic sums of the cyclic sets in a sum alignment (wherein cycles of opposite aspect, ascending with descending, are aligned).

[7] The array in its various alignments provides the resources for melodic and harmonic material in a Perlean composition. A hexachordal collection known as an axis-dyad chord is the main unit segmented from an array, and is formed by combining trichords from each of the cyclic sets. Figure 5a displays one segment, comprised of trichords 7-7-2 and 7-5-2. If the 0,7 cyclic set were rotated eight times clockwise (or four times counter-clockwise), the resulting axis-dyad chord would contain trichords 7-7-2 and 9-3-4. Perle regards multiple appearances of a pc within a segment as independent elements. Since any collection may include pc duplication, therefore, the hexachordal axis-dyad chord may contain less than six distinct elements.

[8] All axis-dyad chords segmented from the same array are isomorphic. Due to the symmetrical nature of the array, chords generated from an even-numbered rotation of the cyclic sets within the array (where the aspect of the aligned cyclic sets is retained) are also isomorphic. In the axis-dyad chord’s K-graph in Figure 6 the dotted lines connecting the nodes in the upper and lower trichords indicate the variable status of the two cyclic sets of the array in relation to one another.

K-nets and Array Equivalence

[9] Arrays share equivalence relationships through transposition and inversion. Transposing an array entails adding a constant even or odd integer x to each pc in both cyclic sets, thereby resulting in a constant even integer, 2x, added to each of the array’s tonic sums. (Adding a constant odd integer to each tonic sum constitutes semi-transposition, since the pcs themselves could not be transposed by the same constant value.) For example, transposing each pc in the cyclic sets of array 2,9/0,7 by T3 results in the array 8,3/6,1, whose tonic sums relate to the first array by T6. Although this relationship can be expressed in a single line as T6 (2,9/0,7) = 8,3/6,1, an approach favored by Buchler, this equation in its simplicity omits important information. First, it is not obvious in this equation that the integers being transposed are not pcs, but sums of pcs. In addition, other facts must be gleaned from the equation: the cyclic sets’ intervals remain constant, as do the relationships among the corresponding tonic sums between the cyclic sets. This consistency of relationships produces a strong isography among transposed arrays. Transposing an array affects multiple relationships of pcs, sums, and intervals, which to my mind are represented much more accurately, clearly, and completely through K-nets, as shown in Figure 7a. In addition, the K-graph of Figure 7b captures the recursive structure of all arrays transpositionally related to 2,9/0,7 built on cycles of interval 7, as well as their component elements.

[10] As with transposition, array inversion begins with the pcs of the cyclic sets, each of which is inverted by a constant even or odd value. Consequently, the corresponding tonic sums between the two arrays will sum to the same even value. (Those tonic sums that add up to an odd integer constitute semi-inversion, where the component pcs were not inverted by the same value.) Further, the inverted array’s cyclic intervals are not retained, but transform into complementary cycles.

[11] An I2 inversion of an array could be represented simply as I2 (2,9/0,7) = 0,5/2,7. But as described above, additional significant relationships between the corresponding cyclic intervals and tonic sums are not apparent in this equation. These relationships are included as an integral part of the K-nets in Figure 8a, just as they are in the arrays themselves. These particular K-nets are negatively isographic, which means that the corresponding T-values are complementary while the I-values add up to the same sum. The “negative isography” designation troubles Buchler, yet, in this context, is in no way at odds with Perle’s original conception of inversionally-related arrays; rather, it faithfully expresses their manifold relationships. This particular type of relationship obtains for all such arrays inverted by a consistent value, as indicated in Figure 8b’s K-graph of recursive structure of I2-related arrays.

[12] All of the above notwithstanding, I do share several of Buchler’s concerns about K-nets, most especially the ease with which an analyst can manipulate K-nets to “show” whatever the analyst wishes, whether or not they are a true reflection of the musical surface. But in basing my work on Perle’s music on Perle’s own compositional theory, no other tools have proven to be more effective than K-nets in representing the myriad, contextual relationships.

[13] Although I have confined my response to the most fundamental aspects of Perle’s method, it should be known that twelve-tone tonality itself is a hierarchical system, with arrays constituting the first “level” of structure.(1) Buchler rightly points out that K-net recursion shows relational structures rather pitch or pc recursion, in contrast to Schenkerian middleground and background levels, which do retain notes from foreground events. Nonetheless, I disagree with Buchler’s assertion that K-net hierarchies cannot yield the same degree of consistency. In a Schenkerian analysis, notes retained from surface levels may change in function at deeper levels, depending on the context. In the K-graphs generated for this article, it is true that notes were removed to show recursion, but the corresponding relationships remained constant. I contend that K-net hierarchies can indeed portray a high level of consistency. The crucial difference here is the entities retained at each level of hierarchy, notes versus relationships.

[14] One final point to address concerns Buchler’s assertion: “And, of course, all chords need to contain the same number of notes or else some notes need to be duplicated within a surface K-net, since no one has yet suggested a way of relating different sizes of networks” [paragraph 65]. On the contrary, I addressed this very issue in a paper delivered at the 2005 meeting of the Society for Music Theory.(2) Using successions of K-nets with four and five nodes, I modeled tetrachordal and pentachordal segments naturally occurring throughout Perle’s song “There Came a Wind Like a Bugle” thereby relating unordered segments from the musical surface to the underlying, pre-compositional array. As a rejoinder to Buchler’s concluding statement that he “just wants to be certain that [his] analytical tools help [him] elucidate more complexities than they introduce” I can say with confidence that in the specific situation of Perlean analysis, K-nets are the most appropriate and efficient tools I’ve used to date.

Gretchen C. Foley

University of Nebraska-Lincoln

gfoley@unlnotes.unl.edu

Footnotes

1. For a detailed explanation of these hierarchical levels the reader may refer to George Perle,

Twelve-Tone Tonality, 2nd ed. (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1996) or Gretchen Foley “Pitch and Interval Structures in George Perle’s Theory of Twelve-Tone Tonality” (Ph.D. diss., University of Western Ontario, 1999).

Return to text

2. A revised version of this presentation will be available in the upcoming issue of

Theory and Practice as Gretchen C. Foley, “Sum Squares and Pentagrams: Two New Tools for Perlean Analysis” (Theory and Practice 32, 2007).

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2007 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason, Managing Editor and Stefanie Acevedo, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits: