The Progress of a Motive in Brahms’s Intermezzo op. 119, no. 3 *

Adam Ricci

KEYWORDS: motive, Grundgestalt, Brahms, double-tonic complex, Intermezzo

ABSTRACT: Brahms’s Intermezzo op. 119, no. 3 is structured around a motive with two components—one melodic, one harmonic—that operate sometimes separately and sometimes together. The global harmonic trajectory of the piece is embodied in the combination of these two components; local harmonic motion proceeds through an expanded LR-cycle, with periodic short cuts from one zone of the cycle to another. The A section unfolds a double-tonic complex while introducing chromatic pitch classes in a carefully planned order; the B section is densely chromatic, featuring interlocking transpositions of the harmonic component. Rhythmic transformations of the motive are also addressed, including a previously unnoted motivic connection with op. 119, no. 2.

Copyright © 2007 Society for Music Theory

[1] Johannes Brahms’s skill with motivic development is well known. Beginning with Arnold Schoenberg’s famous essay “Brahms the Progressive,”(1) analysts have demonstrated time and time again the masterful ways in which Brahms manipulates his motivic ideas.

[2] Motivic development is especially concentrated in the late piano music op. 116 through 119, written in 1892 and 1893. About op. 118, no. 6, for instance, John Rink (1999, 97) writes that “to characterize [this piece] as a motive in search of a tonic would hardly do justice to the tremendous dramatic impulse generated by Brahms’s incessant reharmonizations of the almost ubiquitous melodic shape.” Notable about many of these pieces is the extreme economy of material: the way in which a single idea is transformed in myriad ways.(2)

[3] Among the op. 119 pieces, No. 1 has received the most analytic attention.(3) Op. 119, no. 2 has also been studied at length, particularly for its re-casting of a six-pitch motto introduced in the A section in the B section.(4) The literature on Nos. 3 and 4 is relatively scant, however, quite possibly for opposite reasons: whereas No. 4 is the longest, weightiest and most complex in the set, No. 3 is, at least on the surface, the most innocuous. No. 4 is treated in a recent dissertation by Samuel Ng and a paper by Frank Samarotto;(5) the only relatively comprehensive analysis of No. 3 is in a dissertation by Camilla Cai.(6) The lighthearted mood of No. 3 masks an underlying sophistication: the piece is remarkable, not only for its economy of material, but also for its use of a double-tonic complex and its serial ordering of chromatic pitch classes, two musical procedures not usually associated with the music of Brahms.(7) That the motive is exclusively diatonic places the chromaticism into especial relief.

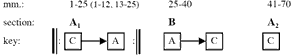

[4] Like many of the late piano pieces (and like the first two in op. 119), the Intermezzo is in ternary form, as shown in Example 1. Section A1 is in two nearly identical parts, each of which progresses from C major to A major; the B section moves from A major back to C major; and section A2 is exclusively in C.

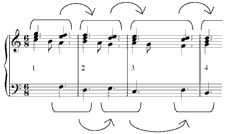

[5] In its first appearance, the motive embodies these two keys, which in section A1 form a double-tonic complex. Before examining the double-tonic complex in more detail, we must first examine the motive itself. It consists of the melodic cell and harmonic progression given in Example 2. The melodic cell, labeled “J”, consists of the interval pattern ascending 3rd, ascending 2nd and descending 2nd. A clef is omitted from the first part of the example because J appears in different scale locations in different parts of the piece. J’s first occurrence begins on .

[6] The harmonic component of the motive is dubbed “DOWN-THIRD-UP-FIFTH” after its constituent root motions. In all statements of this harmonic progression, the descending third is diatonic—the quality of the third depending upon the quality of the starting chord—and the ascending fifth is perfect. In this first appearance, the descending third is minor. Moreover, the total pitch-class content of the progression in its first appearance is diatonic.

[7] The melodic cell and harmonic progression—J and DOWN-THIRD-UP-FIFTH— sometimes occur independently, but for the most part interact to create a larger unit. This larger unit, given at the bottom of Example 2, is the motive of my title.(8) Again, the fact that the motive is exclusively diatonic is significant, because it makes the chromatic pitch classes especially salient.

[8] The opening of the piece animates the motive by repeating and varying the duration of J while arpeggiating the chords of DOWN-THIRD-UP-FIFTH. Example 3 annotates the melody of m. 1 through the downbeat of m. 3, which fuses together three Js.(9) By fusing together three Js and altering the duration of the final pitch of each J (the durations are ![]() ,

, ![]() , and

, and ![]() , for the three occurrences, respectively), Brahms creates a symmetrical rhythmic structure.(10) The dots below the staff indicate metric position: two dots indicate a strong beat, one dot a weak beat.(11) The first J starts on a strong beat and concludes on a weak beat. The third J starts on a weak beat and concludes on a strong beat. The middle J begins and ends on a weak part of two different beats. This rhythmic organization marks the beginning and ending of thrice-J as points of departure and arrival.(12) Furthermore, mm. 1–3 constitute a single hypermeasure: the sequence beginning in m. 4 retrospectively marks that measure as a hypermetric downbeat, segregating mm. 1–3.

, for the three occurrences, respectively), Brahms creates a symmetrical rhythmic structure.(10) The dots below the staff indicate metric position: two dots indicate a strong beat, one dot a weak beat.(11) The first J starts on a strong beat and concludes on a weak beat. The third J starts on a weak beat and concludes on a strong beat. The middle J begins and ends on a weak part of two different beats. This rhythmic organization marks the beginning and ending of thrice-J as points of departure and arrival.(12) Furthermore, mm. 1–3 constitute a single hypermeasure: the sequence beginning in m. 4 retrospectively marks that measure as a hypermetric downbeat, segregating mm. 1–3.

[9] The textural and harmonic context also support hearing mm. 1–3 as a unit. The melody, beginning with thrice-J, is in an inner voice, played by the inside of the pianist’s right hand. The upper voices support the rhythmic structure just discussed, with dotted quarter notes at the conclusion of the first and third instances of J only. Harmonically, the conclusion of thrice-J coincides with the conclusion of the first DOWN-THIRD-UP-FIFTH. In the first two statements of J, the third pitch (A) is not harmonized; rather, it is an upper neighbor to the chordal 5th. But in the third statement of J, when A descends to G it pulls C down to B, and the bass complies: the bass pattern in m. 3 is a transposition up a 3rd of that in mm. 1 and 2. Consequently, the last eighth of m. 2 sounds more like an independent harmony—a bona fide A-minor triad—than the “mere” neighbors in the first two Js. Put another way: while the first two inner-voice As are complete neighbors to the 5th of the tonic triad, the third A bridges two different harmonies, C major and E minor.(13) In dramatic terms, it is as if the incessant repetition of J induces the harmonic motion across the barline of mm. 2–3. To paraphrase Schoenberg, pitch class A is the “tonal problem” of the piece, creating an imbalance that the rest of the piece serves to rectify.(14)

[10] J’s suggestion of an A-minor harmony is played out by the music that follows. The keys of C major and A minor (later inflected to major) “compete” with each other, interacting in a double-tonic complex.(15) In m. 3 (pickup to beat 2), J begins a fourth time but does not complete the neighbor figure; instead, the melody continues upward –––, forcing the upper voices to shift upward. The voice that descended from C to B (on the downbeat of m. 3) has thus returned to C; the right hand plays a C-major triad, seemingly assenting to the C-major tonic and banishing the problem pitch class A. But the bass, instead of returning to C as well, moves to A—belatedly reinforcing the persistent A in the right-hand part of mm. 1–2. The sonority on the downbeat of m. 4 is ACEG, the combination of an A-minor triad and C-major triad.

[11] This “miscommunication” between the hands continues. The left-hand part in mm. 4–5 seemingly tries to establish A minor with the bass line –––, and the right-hand

part articulates a sequence that descends by step beginning in m. 4, landing on an A-minor triad in m. 6. But A minor’s leading tone,

Example 4. A Prototype for mm. 4–12

(click to enlarge)

Example 5. Sequence with Alterations, mm. 4–9

(click to enlarge)

[12] Two dovetailed sequences—incorporating significant alterations—occur in mm. 4–12, a passage whose hypermeter is the most complex of the piece. The alterations introduce the first chromatic pitch classes. Example 4 sets the stage for discussing these alterations by providing a 4-measure (and 4-hyperbeat) prototype for mm. 4–12 that ends with a half cadence. The prototype removes the A-vs.-C conflict at the beginning of m. 4 by transposing the circled bass pitches up a 3rd, and cadences on the dominant in m. 7, removing the large phrase expansion in the music while also normalizing the irregular hypermeter of this section.(17) The sequence here continues the rhythmic pattern of the melody of m. 3.

[13] Example 5 approaches the musical score in two stages. In part a. is an unaltered sequence based on the music of mm. 4–5.(18) As shown at b., Brahms alters the sequence

by first repeating the chord in m. 6—indicated by the dotted portion of the curved brackets—and by changing E to ![]() position, the chord sounds like a tonic due to the cadential figure – in the

inner-voice melody. For this reason, the prototype in Example 4 places the chord here in

position, the chord sounds like a tonic due to the cadential figure – in the

inner-voice melody. For this reason, the prototype in Example 4 places the chord here in position; the melody’s ascending-4th leap (m. 7, b. 2 of the score) is conceptually a bass voice that has been transferred to an inner voice and metrically displaced.

[14] As shown below the staff in part b., part of the previous pattern is absorbed into a new two-measure pattern that participates in an ascending-second sequence; mm. 8–9 may be heard as an internal phrase expansion, repeating the hypermetric “3–4” of mm. 6–7.(21) Since the second pattern of this new sequence begins with a diminished triad instead of a minor one, there is no room for the chromatic descending line found in the top voice of the first pattern, necessitating an alteration; strikingly, this alteration employs the same two chromatic pitch classes as the earlier one— position this time. The chord is still on a weak beat, however, and its arrival is undermined by a drawn-out 4-3 suspension. The threefold repetition of the pitch material in mm. 9–11 retrospectively causes a reinterpretation of m. 9 as a hypermetric downbeat.(22) Two chromatic pitch classes then revert to their diatonic form:

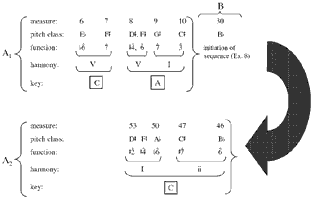

[15] The chromatic pitch classes introduced in mm. 4–10 act as agents in the double tonic complex. Example 6 collates these pitch classes, listing their location and harmonic function. Witness again the pure diatonicism of mm. 1–6 (b. 1) and the context in which

[16] The second half of A1 is identical in pitches and rhythms to its first half until the last eighth of m. 23.(24) This time, the 4–3 suspension resolves within the beat; in place of the earlier line D– in the piece, followed by the first strong cadence, in A major.

[17] After its prominent statement at the opening of each half of A1, the motive recedes from the foreground until section B; only its harmonic component, untransposed, remains present but not very prominent. The bass motions from A to E in mm. 4–5 (by way of intervening chords) and in mm. 8–9 echo the same motion in mm. 2–3. In the B section, the motive remains closer to the foreground; in particular, DOWN-THIRD-UP-FIFTH is subject to a most remarkable working-out. The route from C major to A major was relatively straightforward; the route back is not so simple.

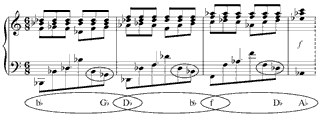

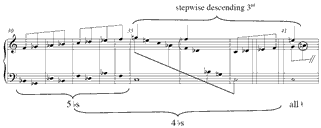

[18] In m. 25, thrice-J returns, but the lack of accompaniment, low register, and sudden piano undermine A major’s big moment. J begins here on rather than , so J and DOWN-THIRD-UP-FIFTH have been transposed by different intervals relative to m. 1: J is transposed down a 5th, while DOWN-THIRD-UP-FIFTH is transposed down a minor 3rd. As shown in Example 7, mm. 25–29 outline a statement of DOWN-THIRD-UP-FIFTH beginning on A major and concluding on

[19] Example 8 illustrates how the music navigates from the DOWN-THIRD-UP-FIFTH on A to the climactic one on

[20] As shown in Example 9, the underlying voice-leading pattern established by the sequence continues beyond the conclusion of the sequence (m. 33), and even beyond the conclusion of the DOWN-THIRD-UP-FIFTH chain (m. 35). The example highlights instances of the Phrygian tetrachord (half-whole-whole).(28) The first two tetrachords (on F, then on C) are straightforward reductions of the melody. The thunderous arrival on a C-major triad, the goal of the whole passage, contains a less obvious statement of the next tetrachord in the pattern (beginning on G) embedded within a series of descending 3rds. At the same time, the pitches on successive downbeats—G and F—set up an expectation for

Example 10. Inexact Augmentation of J in mm. 39–41 and its Overlap with the Recapitulatory J

(click to enlarge)

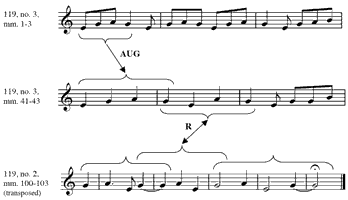

Example 11. Augmentation of J in mm. 41–43 as Reference to op. 119, no. 2

(click to enlarge)

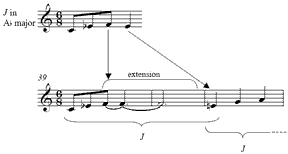

[21] In the forte DOWN-THIRD-UP-FIFTH statement (mm. 33ff.), F minor sounds like tonic and C major like dominant. Rhetorically, the passage beginning in m. 35 sounds like a retransition. Coinciding with the small-scale echo in mm. 39–41 is a re-introduction of J given in Example 10. When we hear C-

[22] The overlap between two forms of J here is only one way in which the music disguises the return of the opening material. Tonally, C major was ushered in as a dominant of F minor (m. 35); but what is initially heard as a dominant is actually the tonic: what first sounds like i to V is really—or rather, becomes—iv to I. Brahms exploits this well-known ambiguity of the tonal system to marvelous effect here.(31) Rhythmically, the statement of J beginning on

[23] And speaking of retrogrades, the chromatic pitch classes in section A2 occur in

retrograde order relative to section A1 plus B. (See again

Example 6.) First comes

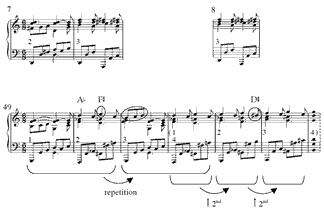

[24] Section A2 is dominated by a lengthy dominant prolongation (mm. 49–65) that reworks the music of mm. 7ff. As shown in Example 12, m. 49 is a transposition of m. 7 down a perfect 5th, an instance of sonata principle; coincident with this transposition is a

reversal of strong and weak hypermetric beats that results from the absolute hypermetric regularity of mm. 25–48.(36) Relative to the transposition of m. 7 in m. 49, the music of m. 50 is a whole step too low relative to m. 8; this transposition up a minor 3rd (or down a major 6th) produces pcs

[25] After the highly chromatic journey of the B section, pitch class A presents less of a threat than it did in section A1. The only

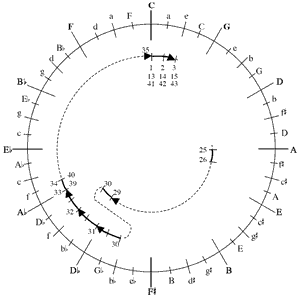

[26] Example 13 summarizes the harmonic trajectory of the piece. The boldface pitch classes in part a. constitute a circle of ascending perfect 5ths; here the letter names stand for triads. Conceptually, we can think of this circle of 5ths first being embellished by the chords at the half hours that fill in each 5th with two diatonic 3rds, producing the 24-triad LR-cycle.(42) Next, each ascending 3rd is filled in by a DOWN-THIRD-UP-FIFTH, producing a 48-triad cycle that comprises a complete chain of DOWN-THIRD-UP-FIFTHs. The piece traverses only segments of this cycle, as shown by the arcs inside the

circle; each arc is labeled with measure numbers. The short cuts across the circle in mm. 26–29 and 34–35 correspond to the two forms of DOWN-THIRD-UP-FIFTH that frame the B section, the two that, unlike all the others, begin and end with major

[27] Part b. of Example 13 shows how the length of DOWN-THIRD-UP-FIFTH changes throughout the piece: the first two instances—those in the A section—are two measures long measured from downbeat to downbeat. The next two, really one embedded within another, take 2 1/2 and 4 measures. After this lengthening of DOWN-THIRD-UP-FIFTH, it is suddenly contracted: three statements in the span of only three measures. The normative two-measure length of DOWN-THIRD-UP-FIFTH returns at the point at which J disappears, in m. 33.

[28] My own initial impression of the Intermezzo was of blandness: the absolute diatonicism—in C major, no less!—of the opening and the seemingly meandering harmonic progression discouraged me from continuing beyond the first two lines or so. It was only after taking a closer look that I began to marvel at what Brahms has done here: it no longer seemed bland at the beginning, but subtle, with the diatonicism establishing the tonal problem and throwing each chromatic pitch class into especial relief. The densely chromatic B section, with its lengthy DOWN-THIRD-UP-FIFTH chain and regular hypermeter, complements the sparsely chromatic and hypermetrically irregular A1 section. The strict ordering of the five chromatic pitch classes in the first half of the piece and the reversal of this ordering in the second half is remarkable, and warrants further investigation in the rest of Brahms's oeuvre.

Adam Ricci

UNC at Greensboro School of Music

P.O. Box 26170

Greensboro, NC 27402-6170

adam_ricci@uncg.edu

Works Cited

Bailey, Robert, ed. 1985. Prelude and Transfiguration from Tristan und Isolde: The Authoritative Scores, Historical Background, Analytical Essays, Textual Notes, Program Notes, Critical and Aesthetic Commentaries. New York: W.W. Norton.

Baker, James. 1993. “Chromaticism in Classical Music.” In Music Theory and the Exploration of the Past, ed. Christopher Hatch and David W. Bernstein, 233–307. Chicago: University of Chicago.

Braus, Ira. 1994. “An Unwritten Metrical Modulation in Brahms’s Intermezzo in E minor, op. 119, no. 2.” In Brahms Studies, vol. 1, ed. David Brodbeck, 161–69. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Brinkmann, Reinhold. “Anhand von Reprisen.” In Brahms-Analysen: Referate der Kieler Tagung 1983, ed. Friedhelm Krummacher and Wolfram Steinbeck, 107–20. London: Bärenreiter, 1984.

Burnett, Henry and Shaugn O’Donnell. 1996. “Linear Ordering of the Chromatic Aggregate in Classical Symphonic Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 18.1: 22–50.

Cadwallader, Allen. 1983. “Motivic Unity and Integration of Structural Levels in Brahms’s B Minor Intermezzo, op. 119, no. 1.” Theory and Practice 8.2: 5–24.

—————. (1988). “Foreground Motivic Ambiguity: Its Clarification at Middleground Levels in Selected Late Piano Pieces of Johannes Brahms.” Music Analysis 7.1: 59–91.

—————. 1999. “Schenker’s Unpublished Work with the Music of Johannes Brahms.” In Schenker Studies 2, ed. Carl Schachter and Hedi Siegel, 26–46. Cambridge: Cambridge University.

Cai, Camilla. 1986. “Brahms’ Short, Late Piano Pieces’Opus Numbers 116–119: A Source Study, An Analysis and Performance Practice.” Ph.D. diss., Boston University.

Carpenter, Patricia. 1988. “A Problem in Organic Form: Schoenberg’s Tonal Body.” Theory and Practice 13: 31–63.

Clampitt, David. 2004. “In Brahms’s Workshop: Compositional Modeling in op. 40, Adagio mesto.” Paper presented at the Society for Music Theory conference, Seattle, WA.

Clements, Peter. 1977. “Johannes Brahms: Intermezzo, op. 119, no. 1.” Canadian Association of University Schools of Music Journal/Association Canadienne des Ecoles Universitaires de Musique Journal 7: 31–51.

Cohn, Richard. 1997. “Neo-Riemannian Operations, Parsimonious Trichords, and Their Tonnetz Representations.” Journal of Music Theory 41.1: 1’66.

Dunsby, Jonathan. 1981. Structural Ambiguity in Brahms: Analytical Approaches to Four Works. Ann Arbor: UMI.

Frisch, Walter. 1990. “Brahms: From Classical to Modern.” In Nineteenth-Century Piano Music, ed. R. Larry Todd, 316–54. New York: Schirmer Books.

Harrison, Daniel. 2002. “Dissonant Tonics and Post-Tonal Tonality.” Paper presented at the Music Theory Society of New York State conference, New York, NY.

Hook, Julian L. 2002. Uniform Triadic Transformations. Ph.D. dissertation, Indiana University.

Jersild, Jøgen. 1982. “Harmoniske Sekvenser i Dur- og Mol-tidens Funktionelle Harmonik.” Dansk Årbog for Musikforskning 13: 73–108.

Jordan, Roland and Emma Kafalenos. 1989. “The Double Trajectory: Ambiguity in Brahms and Henry James.” 19th-Century Music 13.2: 129–44.

Lerdahl, Fred and Ray Jackendoff. 1983. A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Lewin, David. 1990. “Brahms, His Past, and Modes of Music Theory.” In Brahms Studies: Analytical and Historical Perspectives (Papers delivered at the International Brahms Conference, Washington, DC, 5–8 May 1983), ed. George S. Bozarth, 13–27. Oxford: Clarendon.

Mainka, J’rgen. 1986. “Permutation bei Brahms.” Beiträge zur Musikwissenschaft 2: 145–47.

Nattiez, Jean-Jacques. 1975. Fondements d’Une Sémiologie de la Musique. Série “Esthétique,” ed. Mikel Dufrenne. Paris: Union Générale d’éditions.

Newbould, Brian. 1977. “A New Analysis of Brahms’s Intermezzo in B Minor, op. 119, no. 1.” Music Review 38.1: 33–43.

Ng, Samuel. 2005. “A Grundgestalt Interpretation of Metric Dissonance in the Music of Johannes Brahms.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Rochester.

Petersen, Peter. 1999. “Rhythmische Komplexität in der Instrumentalmusik von Johannes Brahms.” In Johannes Brahms: Quellen-Text-Rezeption-Interpretation, ed. Friedhelm Krummacher and Michael Struck, 143–58. München: G. Henle.

Platt, Heather. 2003. Johannes Brahms: A Guide to Research. New York: Routledge.

Quigley, Thomas. 1990. Johannes Brahms: An Annotated Bibliography of the Literature through 1982. Metuchen, NJ: The Scarecrow Press, Inc.

—————. 1998. Johannes Brahms: An Annotated Bibliography of the Literature from 1982 to 1996. Latham, Maryland: Scarecrow Press, Inc.

Ricci, Adam. 2002. “A Classification Scheme for Harmonic Sequences.” Theory and Practice 27: 1–36.

—————. 2004. “A Theory of the Harmonic Sequence.” Ph.D. dissertation, University of Rochester.

Rink, John. 1999. “Opposition and Integration in the Piano Music.” In The Cambridge Companion to Brahms, ed. Michael Musgrave, 79–97. Cambridge: Cambridge University.

Rosen, Charles. 1990. “Brahms the Subversive.” In Brahms Studies: Analytical and Historical Perspectives (Papers delivered at the International Brahms Conference, Washington, DC, 5–8 May 1983), ed. George S. Bozarth, 105–19. Oxford: Clarendon.

Samarotto, Frank. 2004. “Determinism, Prediction, and Inevitability in Brahms’s Rhapsody in E-flat Major, op. 119, no. 4.” Paper presented at the Society for Music Theory conference, Seattle, WA.

Schoenberg, Arnold. 1975. Style and Idea: Selected Writings of Arnold Schoenberg, ed. Leonard Stein with translations by Leo Black. New York: St. Martins.

Schoenberg, Arnold. 1995. The Musical Idea and the Logic, Technique, and Art of Its Presentation, ed. and trans. Patricia Carpenter and Severine Neff. New York: Columbia University.

Smith, Peter H. 1994. “Liquidation, Augmentation, and Brahms’s Recapitulatory Overlaps.” 19th-Century Music 17.3: 237–61.

2006. “You Reap What You Sow: Some Instances of Rhythmic and Harmonic Ambiguity in Brahms.” Music Theory Spectrum 28.1: 57–97.

Straus, Joseph. 1991. “The Progress of a Motive in Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress.” The Journal of Musicology 9.2: 165–85.

Ulehla, Ludmila. 1966. Contemporary Harmony: Romanticism Through the Twelve-Tone Row. New York: Free Press.

Webster, James. 1978–79. “Schubert’s Sonata Form and Brahms’s First Maturity.” 19th-Century Music 2.1: 18–35 and 3.1: 52–71.

Footnotes

* My title borrows a phrase from that of Straus 1991. Brent Auerbach, Guy Capuzzo, and the anonymous readers for this journal provided helpful comments on the manuscript. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the 2006 meeting of Music Theory Southeast in Chapel Hill, NC.

Return to text

1. Schoenberg 1975, 398–441.

Return to text

2. See also Cadwallader 1988.

Return to text

3. See, for example, Cadwallader 1983, Clements 1977, Dunsby 1981 (Chapter 5), Jordan and Kafalenos 1989, and Newbould 1977. Two excellent guides to Brahms research are Platt 2003 and Quigley (1990 and

1998).

Return to text

4. See, for example, Braus 1994, Frisch 1990,Mainka 1986, and Schenker (unpublished—discussed and

translated in Cadwallader and Pastille 1999).

Return to text

5. Ng 2005; Samarotto 2004.

Return to text

6. Other analyses include Nattiez 1975 and Rosen 1990, both of which focus on the opening 12 measures.

An extensive discussion of rhythm in Op. 119, No. 3 can be found in Petersen 1999.

Return to text

7. One exception is Jordan and Kafalenos 1989, which asserts the

presence of a double-tonic complex involving B minor and D major in op. 119, no.

1. The term “double-tonic complex” originated with Bailey 1985. In an analysis

of the Prelude from Richard Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, Bailey demonstrates

that the keys of A (major/minor) and C (major/minor) are inextricably

intertwined. That the two keys are intertwined does not preclude the superior

position of one key at any given moment. On the structural role of aggregate

completion in tonal music, see Baker 1993 and Burnett and O’Donnell 1996.

Burnett and O’Donnell additionally argue for the significance of particular

orderings of the chromatic aggregate. Clampitt 2004 points out the

correspondence between completion of the aggregate and the end of the exposition

in the Adagio mesto of Brahms’s Horn Trio in

Return to text

8. In that it contains multiple components, is an abstraction from the musical

surface, and is pervasively present in the piece, it is close in function to

Schoenberg’s Grundgestalt; Schoenberg used the term “motive” to designate

smaller musical units. Because the precise meaning of Grundgestalt is difficult

to discern, I will exclusively use “motive” to refer to the combination of J and

DOWN-THIRD-UP-FIFTH. On the conceptual distinctions between motive,

Grundgestalt, and related terms in Schoenberg’s writing, see Schoenberg 1995.

Return to text

9. A fourth statement of J begins on the last eighth of m.

3, beat 1, but is interrupted when the melody ascends to B instead of descending

to G.

Return to text

10. Petersen (1999, 151) shows the lengths of the three Js in his Example 9 and mentions in his accompanying text how it does not fit into the notated 6/8 meter.

Return to text

11. This notation is employed in Lerdahl and Jackendoff 1983.

Return to text

12. Petersen’s (1999) calculus of accents, which takes into account melodic, textural and harmonic factors

and is summarized in his Example 12 (p. 153), clearly places the next strong accent following the

downbeat of m. 1 on the downbeat of m. 3. (It is questionable, however, whether his methodology of

summing all types of accents is valid, because—as he acknowledges (pp. 154–55)—not all of them are

performed accents.) Along similar lines, Cai (1986, 304) states “the first two measures, retrospectively,

[give] the impression of being upbeats to m. 3 where G, the important motive note, corresponds with the

downbeat.” There is another kind of rhythmic symmetry that spans all of mm. 1–3: the durations are

retrograde-symmetric about the middle of m. 2 (Cai 1986, 288).

Return to text

13. Hook (2002, 142) concurs, saying that the A-minor triad “acquires some significance by the

fact that it is the sonority heard immediately preceding the E-minor triad.” In

contrast, Nattiez (1975, 323) does not differentiate the verticality on the last

eighth of m. 2 from the third eighth of m. 1 and second eighth of m. 2; in his

lower-level harmonic analysis, they are all analyzed as VI.

Return to text

14. “Every tone which is added to a beginning tone makes the meaning of that tone doubtful...In this

manner there is produced a state of unrest or imbalance—The method by which balance is restored seems

to me the real idea of the composition” (Schoenberg 1975, 123); “This unrest is expressed almost always

already in the motive, but certainly in the gestalt” (Schoenberg 1995, 107). See also Carpenter (1988, 37–

38), which discusses both quotations.

Return to text

15. To be sure, the double-tonic complex in this piece is considerably weaker than in the pieces to which

Bailey originally applied the term. Nonetheless, it serves as a useful heuristic for understanding the

opening measures of the Intermezzo in particular.

Return to text

16. This C completes the second pattern of a sequence,

however, as I show in

Example 5.

Return to text

17. Rosen (1990, 115, Ex. 16b) includes a 2-voice, 3-measure prototype that is consonant with mine. His

example transposes the left-hand part of m. 4, b. 1 up a 5th instead of a 3rd (representing this voice by a

single pitch, E), and stops short of the G-major triad in the fourth measure of my Example 4.

Return to text

18. Rosen (1990, 115, Ex. 16a) focuses on the (unaltered) bass line beginning with the second beat of m. 3,

interpreting an implied ascending sequence here (E–A, F–B).

Return to text

19. Cai (1986, 288) recognizes a “rhythmic reversal” in m. 7 but does not mention that it constitutes a return

to the opening.

Return to text

20.

Return to text

21. Or, as given in parentheses in Example 5, mm. 6–9 may be heard

(retrospectively) as a 4-beat hypermeasure. Another, more abstract

interpretation might understand mm. 6–7 as an expanded “3” and mm. 8–9 as an

expanded “4.”

Return to text

22. hat m. 9 constitutes a hypermetric strong beat suggests that the parallel m. 7 might also be interpreted

as a strong beat. In this reading, either there is a hypermetric reinterpretation in m. 7, or mm. 4–6 are

understood to be a triple hypermeasure (like mm. 1–3). While this reading has some merit, I find it

difficult to hear in light of the ascending sequence in mm. 6–9 and for reasons I shall enumerate

later.

Return to text

23. That

Return to text

24. The sostenuto in m. 10 is omitted in m. 22, and a new

crescendo appears in m. 23. These two changes

propel the music into the B section. Also, the accents in mm. 11–12 are replaced with

sfs in mm. 23–24.

Return to text

25. The right-hand part in m. 30 is literally a major 6th

below that in m. 26; the left-hand part in the first half of the measure is

transposed up by major 3rd.

Return to text

26. This sequence differs from the one usually indicated by the moniker “ascending 3rd”; the more common

ascending-3rd sequence pairs root motions by descending second and descending fifth and alternates

diatonic triads and (applied) dominant-7th chords. Jersild (1982) comes close to a label for the sequence

based on DOWN-THIRD-UP-FIFTH, calling the sequence that reverses these two root motions “Rising 5th

in ascending-3rd progression” (“Opadgående kvintfølger i stigende tertstrappe”). The first part of his

label corresponds to “UP-FIFTH” and the second part corresponds to the interval of transposition, the

sum of “DOWN-THIRD” and “UP-FIFTH.” A chromatic version of this sequence appears at rehearsal 2

of Bruckner’s motet “Ecce sacerdos.” For more on sequence classification schemes, see Ricci (2002 and

2004).

Return to text

27. Rosen (1990, 114) also notes the altered bass pitches in these measures relative to the opening, and

points out that each dotted-quarter-note pitch is the root of the harmony beginning the next measure.

Return to text

28. This example is inspired by David Lewin’s study

of cantus-firmus technique in Brahms’s music (Lewin 1990).

Return to text

29. This tetrachord (G-A-B-C) is presented explicitly in mm. 3–4.

Return to text

30. The pianist must therefore be careful not to

overemphasize the return of J at its original pitch level. To reflect the

overlap between these two statements of J, I think it is more appropriate to

play the

Return to text

31. Smith 2006 discusses large-scale examples of this type of harmonic ambiguity in Brahms’s G-major

String Quintet op. 111 and the B-minor Rhapsody op. 79, no. 1.

Return to text

32. This melody also appears at the conclusion of the B section, in mm. 67–71. The absolute durations of the

pitches in mm. 41–43 of op. 119, no. 3 are approximately equivalent to those in the B section and codetta

of op. 119, no. 2.

Return to text

33. Interestingly, the last sounded pitch in op. 119, no. 2 is E4, the first pitch of the melody in op. 119, no. 3.

Return to text

34. Rosen calls the return of the opening material “elliptical,” observing that although the rhythm of J

returns in m. 45, its pitch pattern in augmentation returns in m. 41. On the sophistication of Brahms’s recapitulatory procedures in sonata forms, see Webster 1978 and Smith 1994.

Return to text

35. Brinkmann (1984, 111) observes a parallel between the

Return to text

36. Thus m. 49 continues a process begun in m. 7: the inner-voice figure first introduced in m. 7 is initially

heard as falling on a weak beat, then in m. 9 as falling on a weak beat that is retrospectively interpreted

(through its repetitions in mm. 10–11) as strong, and finally in m. 49 as unambiguously strong.

Return to text

37. The

Return to text

38. All but the upper voice are transposed up by major 2nd in this sequence, but the upper voice’s

diatonicism (except for the

Return to text

39. The progression here echoes that of mm. 12–13, the site of the counterintuitive ![]() -of-V (over a

pedal)

to a cadential

-of-V (over a

pedal)

to a cadential

.

.

Return to text

40. Alternatively, one may hear three complete statements of J in these measures, with overlaps on the

downbeats of mm. 67 and 68: the pianist can suggest this interpretation by slightly emphasizing the left-hand

Gs through the downbeat of m. 69.

Return to text

41. Other examples of this major-mode tonic chord-type occur in the second movement of Schubert’s

first A-major piano sonata (D. 664), the Prelude from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde

(see Bailey 1985), and the

final movement (Der Abschied) from Mahler’s Das Lied von der Erde—the latter two of which intertwine the

same keys as the Brahms Intermezzo. On the use of this tonic chord in twentieth-century music, see

Harrison 2002.

Return to text

42. Beethoven exhausts 19 of the triads in this 24-triad cycle (proceeding counterclockwise, i.e., an RL-cycle)

in mm. 143–76 of the Scherzo from his 9th Symphony. For a study of the properties of this and

other neo-Riemannian cycles, see Cohn 1997; a discussion of the Beethoven

passage appears on p. 36.

Return to text

43. I omit from this example the A-E bass motions in mm.

4-5 and 8-9, which might be interpreted as participating in less well

articulated statements of DOWN-THIRD-UP-FIFTH; the

statement in mm. 8-9 ends with a major-minor 7th chord, perhaps prefiguring the

two short cutting statements in the B section that end with major triads.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2007 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason, Managing Editor and Stefanie Acevedo, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits: