Commentary on Samuel Ng’s review of Peter H. Smith’s Expressive Forms in Brahms’s Instrumental Music: Structure and Meaning in His Werther Quartet

Eric Wen

REFERENCE: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.07.13.4/mto.07.13.4.ng.php

Copyright © 2008 Society for Music Theory

[1] I would like to address an analytic idea proposed by Samuel Ng in his

review of Peter Smith’s monograph on Brahms’s Piano Quartet No. 3 in C minor. In

his discussion of the opening of the first movement, Ng takes issue with Smith’s

reading of the G-major chord in bar 21 as the dominant. Instead, he says that

the appearance of this chord comes as an unexpected surprise. Not only does he

call it “the first striking harmonic event of the piece,” but he also later

describes it as “a truly expressive gesture that eludes virtually any structural

explanation.” Furthermore, he suggests that the G![]() chord appearing two

bars

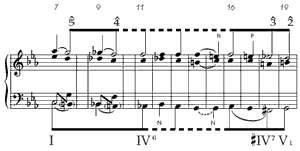

later (bar 23) is the more natural continuation. Ng attempts to find an integral

relationship between form and content, and to “reveal structural intricacies

that may well embody expressive connotations.” His analytic reading of the

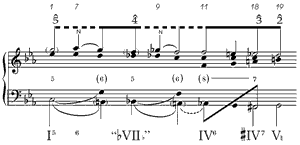

opening theme is, however, surely incorrect. Not only is the G-major chord in

bar 21 the long-expected dominant, but it is the G

chord appearing two

bars

later (bar 23) is the more natural continuation. Ng attempts to find an integral

relationship between form and content, and to “reveal structural intricacies

that may well embody expressive connotations.” His analytic reading of the

opening theme is, however, surely incorrect. Not only is the G-major chord in

bar 21 the long-expected dominant, but it is the G![]() chord that offers the

unexpected surprise. I wish to address this issue not just in order to present

yet another alternative reading, but because the correct interpretation of the

opening of this Brahms Piano Quartet evokes an important Classical tonal

procedure that both Smith and Ng overlook in their analyses.

chord that offers the

unexpected surprise. I wish to address this issue not just in order to present

yet another alternative reading, but because the correct interpretation of the

opening of this Brahms Piano Quartet evokes an important Classical tonal

procedure that both Smith and Ng overlook in their analyses.

[2]

One of the striking features at the beginning of the Brahms Piano Quartet No. 3

in C minor is the quadrupled B![]() that appears in

bar 11, after the half cadence

on the dominant. It transposes the four-octave C at the start of the piece down

a whole step, and ushers in the return of the opening theme in the key of B-flat

minor. Before examining the tonal structure of the antecedent part of the

Quartet (bars 1–31), I would like to discuss the convention of this opening

gesture.

that appears in

bar 11, after the half cadence

on the dominant. It transposes the four-octave C at the start of the piece down

a whole step, and ushers in the return of the opening theme in the key of B-flat

minor. Before examining the tonal structure of the antecedent part of the

Quartet (bars 1–31), I would like to discuss the convention of this opening

gesture.

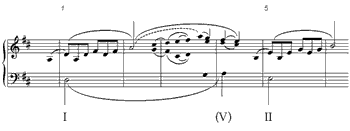

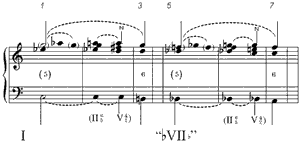

[3] The opening theme of the Brahms is modeled after the Classical construction of two parallel phrases in which the second repeats the opening at a different pitch level. The most usual procedure is to repeat the second phrase a whole step above the initial statement. In Mozart’s Piano Sonata in D, K. 576, for example, the rising arpeggio of the opening theme announced in D major is answered by another statement of the arpeggiated theme in E minor (Example 1). In order to avoid parallel fifths and octaves in the voice-leading from I to II, a dominant chord appearing at the end of the opening phrase serves as a voice-leading corrective. The beginning of Brahms’s Symphony No. 2, op. 73, has a similar construction, but here a B-minor chord, resulting from a 5–6 contrapuntal motion, breaks up the potential parallels between the two statements of the opening theme in D major and E minor (Example 2).

wen_example_info.php|

Example 1. Mozart, Piano Sonata in D, K. 576, i (bars 1–6) (click to enlarge and see the rest) |

Example 2. Brahms, Symphony no. 2 in D, i (bars 1–11) (click to enlarge and see the rest) |

Example 3. The chordal succession of I to

(click to enlarge)

Example 4. Beethoven, Piano Sonata in C, op. 53, “Waldstein,” i (bars 1–9)

(click to enlarge)

Example 5. Beethoven, Piano Sonata in G, op. 31, no. 1, i (bars 1–26)

(click to enlarge)

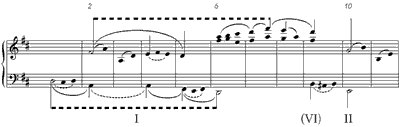

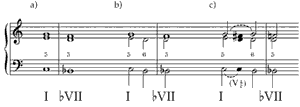

[4]

While the parallel construction of two phrases on adjacent ascending steps

appears rather frequently in the major mode, the reverse situation, of answering

a phrase down by step, occurs much less often. In fact, in major, an answering

phrase on VII is not possible if it remains in its normal form as a diminished

triad. In order to enable such a repetition,

![]() must be chromatically altered to

must be chromatically altered to

![]()

![]() , transforming VII into a major triad.(1) The beginning of Beethoven’s “Waldstein” Sonata presents such a procedure; following the opening theme’s

initial statement in the tonic C major, it appears four bars later in B-flat major. Example 3 shows how a contrapuntal 5–6 motion breaks up the potential parallels in the stepwise motion from I to

, transforming VII into a major triad.(1) The beginning of Beethoven’s “Waldstein” Sonata presents such a procedure; following the opening theme’s

initial statement in the tonic C major, it appears four bars later in B-flat major. Example 3 shows how a contrapuntal 5–6 motion breaks up the potential parallels in the stepwise motion from I to ![]() VII.

VII.![]() chord in this contrapuntal progression is tonicized by an applied

chord in this contrapuntal progression is tonicized by an applied ![]() chord.

chord.

[5]

The initial statement of the opening theme at the beginning of the “Waldstein”

would appear to lead to its repeated statement in B-flat. However, the first

four bars are repeated over bars 5–8, and a descending chromatic bass results.

In the larger tonal organization, it is actually the

![]() chord in

bar 7 that

carries forth the progression from the opening tonic. Essentially, the initial

and final chords in the pair of 5–6 contrapuntal patterns articulate the motion

from I to IV6.(2) As shown in Example 4, this progression from I to IV6 ultimately

leads to V7 in bar 9. Scale degree 4 in the top voice of IV6 prepares the

dissonant seventh above V7. Furthermore, Beethoven emphasizes the motion to the

dominant by transforming IV6 to its minor form, creating a half-step motion from

A

chord in

bar 7 that

carries forth the progression from the opening tonic. Essentially, the initial

and final chords in the pair of 5–6 contrapuntal patterns articulate the motion

from I to IV6.(2) As shown in Example 4, this progression from I to IV6 ultimately

leads to V7 in bar 9. Scale degree 4 in the top voice of IV6 prepares the

dissonant seventh above V7. Furthermore, Beethoven emphasizes the motion to the

dominant by transforming IV6 to its minor form, creating a half-step motion from

A![]() to G in the bass.

to G in the bass.

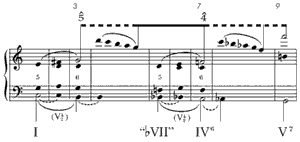

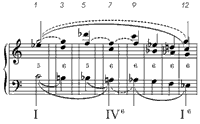

[6]

A variant of the progression found in the antecedent part of the “Waldstein”

occurs at the beginning of Beethoven’s earlier Piano Sonata in G, op. 31 no. 1.

Example 5 presents the tonal structure of the opening theme. In the descending

5–6 motion, root-position triads replace the

![]() chords, and each of these

root-position substitutions is itself tonicized by the subsidiary progression II–V. In the overall tonal structure, however, the initial tonic of this movement

ultimately leads to the IV chord that ends the sequential pattern in bar 22.

This IV is expanded to II in the following bar, before continuing to V.

chords, and each of these

root-position substitutions is itself tonicized by the subsidiary progression II–V. In the overall tonal structure, however, the initial tonic of this movement

ultimately leads to the IV chord that ends the sequential pattern in bar 22.

This IV is expanded to II in the following bar, before continuing to V.

[7]

In the two Beethoven sonata examples, the chromatic inflections of

![]() to

to

![]()

![]() ,

which result in statements of the opening theme on

,

which result in statements of the opening theme on

![]() VII, invoke modal mixture.

In pieces in the minor mode, this chromatic alteration is not necessary because

the natural form of VII is already a stable major chord. Because of this,

parallel phrase constructions in which the second phrase repeats the first a

step lower are found more frequently in minor-mode pieces than in major.

However, when this pattern appears in minor,

VII, invoke modal mixture.

In pieces in the minor mode, this chromatic alteration is not necessary because

the natural form of VII is already a stable major chord. Because of this,

parallel phrase constructions in which the second phrase repeats the first a

step lower are found more frequently in minor-mode pieces than in major.

However, when this pattern appears in minor,

![]() VII is usually altered to

VII is usually altered to

![]() VII

VII![]() in

order to preserve a literal repetition of the opening idea. Despite differences

in style and genre, Mozart’s Piano Fantasy in C minor, K. 475, the slow movement

of Brahms’s String Sextet No. 2 in G, op. 36, and the 25th Variation of Bach’s

“Goldberg” Variations all begin exactly in this way.

in

order to preserve a literal repetition of the opening idea. Despite differences

in style and genre, Mozart’s Piano Fantasy in C minor, K. 475, the slow movement

of Brahms’s String Sextet No. 2 in G, op. 36, and the 25th Variation of Bach’s

“Goldberg” Variations all begin exactly in this way.

[8]

A striking example of this procedure occurs at the beginning of the Introduction

to Mozart’s “Dissonance” Quartet, K. 465. Despite the bold voice-leading at the

foreground, the tonal pattern of the first eight bars is virtually the same as

the “Waldstein,” but in minor. There is a chromatically descending bass motion

over the first eight bars, and bars 5–8 are an exact transposition down a whole

step of bars 1–4. However, unlike the “Waldstein,” where the repeated C-major

chords at the beginning leave no doubt as to the key of the piece, the

“Dissonance” Quartet presents the opening tonic far more ambiguously. In the

opening bar, a sustained A![]() 3 enters mysteriously in the viola over the

repeated C3 eighth notes of the cello. Despite this sparse appearance of two

notes, the

3 enters mysteriously in the viola over the

repeated C3 eighth notes of the cello. Despite this sparse appearance of two

notes, the ![]()

Example 6. Mozart, String Quartet in C, K. 465, i (bars 1–5)

(click to enlarge)

Example 7. Mozart, String Quartet in C, K. 465, i (bars 1–8)

(click to enlarge)

Example 8. Mozart, String Quartet in C, K. 465, i (bars 1–12)

(click to enlarge)

[9]

In bar 2, as A![]() 3 in the viola descends to G3, the first violin enters with a

sustained A

3 in the viola descends to G3, the first violin enters with a

sustained A![]() 5, resulting in perhaps the most renowned cross-relation in

tonal music.(3) From a compositional standpoint, the successive juxtaposition of

A

5, resulting in perhaps the most renowned cross-relation in

tonal music.(3) From a compositional standpoint, the successive juxtaposition of

A![]() and A

and A![]() results from maintaining the entries of the canon in the

upper three voices consistently at the temporal span of one beat (Example 6).

However, it is the tonicization of the dominant in bar 3 that necessitates the

appearance of

results from maintaining the entries of the canon in the

upper three voices consistently at the temporal span of one beat (Example 6).

However, it is the tonicization of the dominant in bar 3 that necessitates the

appearance of ![]() .

.![]()

![]() .

.![]() defines the mode of the

Introduction by articulating

defines the mode of the

Introduction by articulating ![]()

![]() , whereas the A

, whereas the A![]() belongs to the harmonies

of the subsidiary progression II

belongs to the harmonies

of the subsidiary progression II![]() – V

– V![]() that leads to the dominant

that leads to the dominant

![]() chord

in bar 3.(4)

chord

in bar 3.(4)

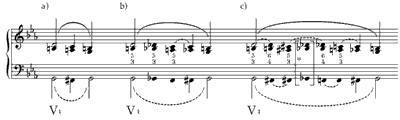

[10]

Following the appearance of the dominant in

![]() position in bars 3–4, the

opening four bars are transposed down a whole step, resulting in a restatement

of the opening phrase in B-flat minor. The G-major

position in bars 3–4, the

opening four bars are transposed down a whole step, resulting in a restatement

of the opening phrase in B-flat minor. The G-major

![]() chord preceding it thus

serves to break up the potential parallel fifths between the successive

whole-step statements of the opening phrase. Looking at the first eight bars in

the larger context of the Introduction, it is the

chord preceding it thus

serves to break up the potential parallel fifths between the successive

whole-step statements of the opening phrase. Looking at the first eight bars in

the larger context of the Introduction, it is the

![]() chord at the end of the

sequential passage (bars 7–8) that represents the important structural goal. As

with the “Waldstein,” it represents IV6, but its function here is to serve as

the midpoint of an arpeggiation down from I to I6 (Example 8).

chord at the end of the

sequential passage (bars 7–8) that represents the important structural goal. As

with the “Waldstein,” it represents IV6, but its function here is to serve as

the midpoint of an arpeggiation down from I to I6 (Example 8).

[11] The opening of the Brahms Piano Quartet No. 3 in C minor follows the Classical model of a minor-mode pairing of phrases in which the initial musical idea presented in the tonic is repeated a step lower and altered to its parallel minor ![]() VII

VII![]() ).

).

[12]

By failing to understand the sequential nature of the consecutive phrases

descending by step, Smith and Ng end up regarding B-flat minor as a distinct key

area.(5) Although Smith reads the arrival of the dominant at bar 21, he doesn’t

explain how the B-flat minor statement of the opening theme gets there. Ng,

meanwhile, is led astray by trying to account for this G-major dominant in the

context of B-flat minor. According to him, the parallel

![]() chords over bars

17–20 are “firmly grounded in B-flat minor.” Because of this, Ng concludes that

“the G-major harmony [in bar 21] hardly sounds like the dominant of the

principal key.” His erroneous pronouncement that the motion to G-major “defies

normative harmonic logic,” leads him to view the G

chords over bars

17–20 are “firmly grounded in B-flat minor.” Because of this, Ng concludes that

“the G-major harmony [in bar 21] hardly sounds like the dominant of the

principal key.” His erroneous pronouncement that the motion to G-major “defies

normative harmonic logic,” leads him to view the G![]() chord in

bar 23 as “the

legitimate resolution of the V7 to VI” in B-flat minor.

chord in

bar 23 as “the

legitimate resolution of the V7 to VI” in B-flat minor.

Example 9. Brahms, Piano Quartet no. 3 in C minor, i (bars 1–21)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Example 10. Brahms, Piano Quartet no. 3 in C minor, i (bars 21–27)

(click to enlarge)

Example 11. Brahms, String Quartet no. 1 in C minor, i (bars 1–7)

(click to enlarge)

Example 12. Brahms, String Quartet no. 1 in C minor, i (bars 7–19)

(click to enlarge)

Example 13. Brahms, String Quartet no. 1 in C minor, i (bars 1–19)

(click to enlarge)

[13]

As Example 9 shows, the G-major chord in bar 21 does represent the arrival on

the structural dominant. The brackets above the graph show the parallelism of

the two phrases that are a step apart. The statement of the opening theme in

B-flat minor appears as part of a sequential pattern that ultimately leads from

I to IV.(6) At the arrival on the subdominant in bar 20, IV6 with the raised form

of ![]() (i.e. A

(i.e. A![]() ) unfolds into a IV7, before making the expected half

cadence on the dominant in bar 21.

) unfolds into a IV7, before making the expected half

cadence on the dominant in bar 21.

[14]

Immediately after the long-awaited arrival on V, the

![]() chord over G

chord over G![]() in

bar 22 comes as an unexpected surprise. This initiates the highly unusual

passage of alternating

in

bar 22 comes as an unexpected surprise. This initiates the highly unusual

passage of alternating

![]() and

and

chords.(7) Not only does this create a feeling

of tonal instability, but it also expresses an atmosphere of uncertainty.

Despite the emotional poignancy of these bars, however, this passage serves to

prolong the dominant over bars 21–27 by a neighboring diminished-third chord in

bar 26 (Example 10). As shown in the successive stages, the F-major chord in bar

25 prepares the chromatic inflection of F–F

![]() in the bass, coinciding with

A–A

in the bass, coinciding with

A–A![]() in the middle voice.

in the middle voice.

[15]

Although the dominant is finally established in bar 27, Brahms attempts once

more to deflect our expectations through the introduction of what Smith dubs as

an “unheimlich” E![]() at the end of

bar 28. The pizzicato Es above the third

G–B

at the end of

bar 28. The pizzicato Es above the third

G–B![]() in

bars 28–30, create the illusion of an E-minor harmony, but, as

Smith correctly notes, it occurs as the midpoint of a 5–

in

bars 28–30, create the illusion of an E-minor harmony, but, as

Smith correctly notes, it occurs as the midpoint of a 5–![]() 6–7 motion above the

dominant.(8)

With the arrival of V9 at bar 31, the antecedent part of the

exposition ends, leading to a forceful restatement of the opening theme in

staccato chords, emphasized by the dynamic marking of forte.

6–7 motion above the

dominant.(8)

With the arrival of V9 at bar 31, the antecedent part of the

exposition ends, leading to a forceful restatement of the opening theme in

staccato chords, emphasized by the dynamic marking of forte.

[16]

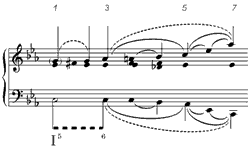

In closing, I would like to mention the opening of Brahms’s String Quartet No. 1

in C minor in relation to the tonal procedure explored in this commentary.(9) The

opening 22 bars of this Quartet represent an extended antecedent that leads to

the dominant in bar 19.(10) Example 11 shows the expansion of an ascending 5–6

contrapuntal motion above the tonic C over the first seven bars. At the arrival

in bar 7 of the climactic

![]() chord with A

chord with A![]() 5 in the top voice, Brahms

initiates a two-bar sequence of parallel

5 in the top voice, Brahms

initiates a two-bar sequence of parallel

![]() chords. As shown in Example 12,

this pattern leads into an expansion of IV6 leading to V in bar 19.

chords. As shown in Example 12,

this pattern leads into an expansion of IV6 leading to V in bar 19.

[17]

Example 13 shows how the motion in parallel ![]() chords over bars 7–10 originates from a descending 5–6 motion with chromatic inflections in the bass. This graph also presents an overview of the entire antecedent part of the Quartet. In bar

18 the IV6 becomes unfolded into a

chords over bars 7–10 originates from a descending 5–6 motion with chromatic inflections in the bass. This graph also presents an overview of the entire antecedent part of the Quartet. In bar

18 the IV6 becomes unfolded into a ![]() IV7 before arriving on the dominant. Unlike

the other examples we have examined, this remarkable opening theme does not

repeat the initial phrase a step lower on

IV7 before arriving on the dominant. Unlike

the other examples we have examined, this remarkable opening theme does not

repeat the initial phrase a step lower on ![]() VII

VII![]() .

.

Eric Wen

Curtis Institute of Music

ericlwen@aol.com

Footnotes

1. In the minor mode, this parallel construction of having

the same theme presented a whole-step apart is not possible due to the fact that

II is a diminished triad. However, if

![]() is lowered to

is lowered to ![]()

![]() ,

resulting in

,

resulting in ![]() II,

this parallelism can also occur. The opening of Beethoven’s “Appassionata”

Sonata with its successive statement of the ominous opening theme in F minor and

G-flat major is only possible through this chromatic alteration.

II,

this parallelism can also occur. The opening of Beethoven’s “Appassionata”

Sonata with its successive statement of the ominous opening theme in F minor and

G-flat major is only possible through this chromatic alteration.

Return to text

2. At the start of the consequent part of the exposition in the “Waldstein,”

following the statement of the opening theme in the tonic over bars 14–17, the

theme is repeated a step higher, resulting in its appearance in D-minor in bar

18. A different tonal connection now occurs between the initial and final chords

in the successive 5–6 patterns. The A-minor

![]() chord in bar 20 connects back to

the tonic, initiating a 5–6 contrapuntal progression above C. This motion from

G to A continues further to A

chord in bar 20 connects back to

the tonic, initiating a 5–6 contrapuntal progression above C. This motion from

G to A continues further to A![]() in bar 22, transforming the tonic into an

augmented-sixth chord that leads to V of the mediant, the key of the “second”

theme.

in bar 22, transforming the tonic into an

augmented-sixth chord that leads to V of the mediant, the key of the “second”

theme.

Return to text

3. Even today, scholars describe the opening of this Quartet as nothing short of

bewildering. Maynard Solomon, in Mozart: A Life (New York: Harper Collins, 1995),

calls the first few bars “an unprecedented network of disorientations,

dissonances, rhythmic obscurities, and atmospheric dislocations

Return to text

4. A similar juxtaposition between A![]() and A

and A![]() in C minor occurs in

bars 12 and 14 of the principal theme in Chopin’s Etude in C minor, op. 10 no. 12, known as the “Revolutionary” Etude. The two notes function the same way as in the Introduction to the “Dissonance” Quartet. Rather than evoking a mysterious atmosphere, however, this conflict takes the form of a

struggle between

in C minor occurs in

bars 12 and 14 of the principal theme in Chopin’s Etude in C minor, op. 10 no. 12, known as the “Revolutionary” Etude. The two notes function the same way as in the Introduction to the “Dissonance” Quartet. Rather than evoking a mysterious atmosphere, however, this conflict takes the form of a

struggle between ![]()

![]() and

and ![]()

![]() , in keeping with

the work’s stormy character.

, in keeping with

the work’s stormy character.

Return to text

5. Although this is not shown in his analytical graph, Smith designates bars 11–20

as “Phrase 2, ![]() vii” in the chart that makes up his Example 3.1.

vii” in the chart that makes up his Example 3.1.

Return to text

6. Curiously, Ng actually notates this harmonic progression through his use of the

Roman numerals “i and iv” at the bottom of his graph. In his discussion,

however, he insists on reading the F-major chord in bar 20 as the dominant of

B-flat minor. Furthermore, he makes the erroneous connection of the IV harmony

in bar 20 to the F-major chord in bar 25.

Return to text

7. These do not make up a 5–6 contrapuntal pattern, as Smith and Ng designate, but

a succession of alternating

![]() and

and

![]() chords, an altogether much more unusual

progression.

chords, an altogether much more unusual

progression.

Return to text

8. Smith discusses this passage in fuller detail in “You Reap What You Sow: Some

Instances of Rhythmic and Harmonic Ambiguity in Brahms,” Music Theory Spectrum

28/1 (2006). As first noted by Donald Francis Tovey in Essays in Musical

Analysis, supplementary volume: Chamber Music (London: Oxford University Press,

1944), this E![]() comes into its own in the recapitulation, where it becomes

realized as an E-minor harmony. This realization of

comes into its own in the recapitulation, where it becomes

realized as an E-minor harmony. This realization of ![]() VI in the key of G provides

the impetus for the remarkable expansion of the major form of the dominant.

VI in the key of G provides

the impetus for the remarkable expansion of the major form of the dominant.

Return to text

9. Readers may wish to compare my (very different) analytical graph of the opening

of the exposition with those of David Lewin in “Brahms, His Past, and Modes of

Theory,” Brahms Studies: Analytical and Historical Perspectives, ed. George Bozarth (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1990) and Robert Morgan in “The

Concept of Unity and Musical Analysis,” Music Analysis 22/1–2 (2003). The later

article was a response to Kevin Korsyn’s essay “Brahms Research and Aesthetic

Ideology,” Music Analysis 12/1 (1993), to which Korsyn in turn responded in “The

Death of Musical Analysis? The Concept of Unity Revisited,” Music Analysis

23/2–3 (2004).

Return to text

10. Smith designates an ABA' formal design at the opening of the Quartet, instead

of the familiar antecedent beginning of an exposition. According to him, the A’

part returns at bar 23 with the appearance of the opening theme in the viola and

cello. Allen Forte also presents this formal scheme in his article “Motivic

Design and Structural Levels in the First Movement of Brahms’s String Quartet in

C minor,” Musical Quarterly 69 (1983).

Return to text

11. Wagner made this remark upon hearing Brahms play the Variations on a Theme by

Handel, op. 24, on February 6, 1864. Although somewhat patronizing, Wagner

grudgingly acknowledged Brahms’s mastery in the Classical variation form. This

was, incidentally, the only occasion the two composers met in person.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2008 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason, Managing Editor and Cara Stroud and Tahirih Motazedian, Editorial Assistants

Number of visits: