Augmented-Sixth Chords vs. Tritone Substitutes

Nicole Biamonte

KEYWORDS: augmented-sixth chords, tritone substitutes, harmony, voice-leading, enharmonic relationships

ABSTRACT: Augmented-sixth chords and tritone substitutes have long been recognized as enharmonically equivalent, but to date there has been no detailed and systematic examination of their relationships from the perspectives of both classical and jazz theories. Augmented-sixth chords and tritone substitutes share several structural features, including pitch-class content, nonessential fifths, underdetermined roots, structural positioning, and two possible harmonic functions: pre-dominant or dominant. A significant distinction can be made between these two chord classes on the basis of their behaviors: they differ in their voice-leading conventions of contrary vs. parallel, normative harmonic function as dominant preparation vs. dominant substitute, and enharmonic reinterpretation as modulatory pivot vs. dual-root dominant approaching a single resolution. In light of these differences, examples of both augmented-sixth chords and tritone substitutes can be identified in both the jazz and art-music repertoires.

Copyright © 2008 Society for Music Theory

Introduction

[1] Augmented-sixth chords and tritone substitutes have long been recognized as enharmonic equivalents. Although this relationship has been briefly noted in a few recent textbooks, to date no in-depth comparison from the standpoint of both classical and jazz theories exists in the scholarly literature.(1) A close consideration of commonalities and differences in structure and function can lead to a richer understanding of both chord types. Their relationship is generally described as two different perspectives on the same syntactic structure: in classical terminology, an augmented-sixth chord; in jazz, a tritone substitute. An obvious distinction in their typical contexts is that augmented sixths are a compositional characteristic of art music from the 18th and 19th centuries, while tritone substitution has been a performance practice in improvised jazz since the bebop era (mid-1940s) or slightly earlier. For purposes of comparison to augmented-sixth chords, I have used examples of tritone substitutes from published arrangements of jazz standards.

[2] The potential harmonic roles of these two chord types are similar: they function either as dominant preparations or as substitute dominants. As I will demonstrate, however, the two chord classes result not simply from different stylistic perspectives on the same musical construct, but from significant differences in normative harmonic function, conventional voice-leading procedures, and possibilities for enharmonic reinterpretation, as reflected in compositional practice. Thus both chord types can be distinguished in both art-music and jazz repertoires.

Augmented-Sixth Chords

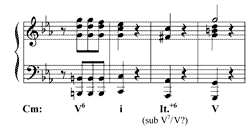

[3] As is well known, the fundamental principle of augmented-sixth chords is

that the defining interval resolves outward in contrary motion to

an octave. In the most common configuration, scale degrees ![]()

![]() and

and

![]()

act as

double leading tones facilitating a strong arrival on V, as in Example 1, from the

opening of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 (1808). In dominant-function augmented

sixths, scale degrees

act as

double leading tones facilitating a strong arrival on V, as in Example 1, from the

opening of Beethoven’s Symphony No. 5 (1808). In dominant-function augmented

sixths, scale degrees ![]()

![]() and

and

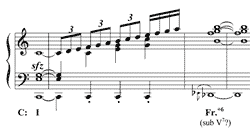

![]() resolve to the tonic, as in

Example 2, the ending

of Schubert’s C-major String Quintet (1828). Since the chord in this instance

is a French augmented sixth, it can also be interpreted as V7 with a flat fifth

in the bass. More rarely, the octave resolution of the augmented-sixth interval

is to the third of the tonic triad, which Daniel Harrison calls the ‘plagal’

augmented sixth because of the 4-3 bass motion, or to the fifth of the tonic

triad, known as a common-tone augmented sixth.(2)

resolve to the tonic, as in

Example 2, the ending

of Schubert’s C-major String Quintet (1828). Since the chord in this instance

is a French augmented sixth, it can also be interpreted as V7 with a flat fifth

in the bass. More rarely, the octave resolution of the augmented-sixth interval

is to the third of the tonic triad, which Daniel Harrison calls the ‘plagal’

augmented sixth because of the 4-3 bass motion, or to the fifth of the tonic

triad, known as a common-tone augmented sixth.(2)

|

Example 1. Augmented Sixth as Pre-Dominant: Beethoven Symphony No. 5, first movement, mm. 18–21 (click to enlarge) |

Example 2. Augmented Sixth as Dominant: Schubert, String Quintet in C, fourth movement, mm. 425–431 (click to enlarge and see the rest) |

Tritone Substitutes

[4] The basis of tritone substitution is that the active interval of the tritone in any dominant-seventh chord is shared by another dominant-seventh chord whose root is a tritone away, as shown in

Example 3.

These harmonies function interchangeably because the tritone is inversionally symmetrical. Thus the chordal thirds and sevenths, which form the tritones, map onto each other, producing smooth voice-leading in either case. In theory, tritone substitutes replace dominants, and this is indeed their most usual function. In practice, however, tritone substitution is also applied to

chords without a tritone—typically dominant preparations such as vi and ii, either preserving the original chord qualities or recasting them as dominant sevenths. Both chords of a ii–V progression are commonly substituted, as in

Example 4, the end of the A phrase from Ellington’s “Satin Doll” (1953).(3) In this instance the minor quality of the ii7 chord has been retained, and the conventional ii–V–I (Dm–G–C) has been replaced by

![]() vi–

vi–![]() II–I (A

II–I (A![]() m–D

m–D![]() –C).

–C).

|

Example 3. Tritone Substitution and Resolution (click to enlarge) |

Example 4. Tritone Substitution for ii7–V7: Ellington, “Satin Doll,” end of A phrase (click to enlarge) |

Example 5. Tritone substitution for iiø7 (II7): Arlen, “Come Rain or Come Shine,” end of chorus

(click to enlarge)

[5] Example 5 shows the ending of Arlen’s “Come Rain or Come Shine” (1946).(4) The song concludes with a fifth-progression, vi–ii–V–I, in which the expected ii chord has been replaced with a dominant seventh on

![]() VI, with some extensions and alterations. The resulting

VI, with some extensions and alterations. The resulting ![]() VI–V progression is less readily identifiable as a tritone substitute than the

VI–V progression is less readily identifiable as a tritone substitute than the

![]() II–I

progression of Example 4, since

II–I

progression of Example 4, since

![]() VI, independently of any substitutions, is one of the most common approaches to the dominant (especially within a descending-tetrachord progression). Hence this form of tritone substitution treats as interchangeable the two most normative approaches to dominant, by descending fifth from ii and by descending semitone from

VI, independently of any substitutions, is one of the most common approaches to the dominant (especially within a descending-tetrachord progression). Hence this form of tritone substitution treats as interchangeable the two most normative approaches to dominant, by descending fifth from ii and by descending semitone from

![]() VI.

VI.

[6] The effect of tritone substitution is to replace root movement by descending fifth with root movement by descending semitone. Robert Morris describes this transformation as equivalent to the multiplicative operation T6MI (or T6M7).(5) However, under MI (or M7) alone, without transposition, the cycle of fifths maps onto the chromatic scale and vice versa, with even-numbered pitch-classes held invariant: the descending fifth-cycle 0 5 10 3 8 1 6 11 4 9 2 7 becomes the descending semitone-cycle 0 11 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 when multiplied by 7. Thus T6MI (T6M7) is equivalent to tritone substitution for fifth-progressions ending on odd-numbered pitch classes, and MI (M7) for fifth-progressions ending on even-numbered pitch classes, so that in either case the goal chord remains the same.

Enharmonic Equivalence

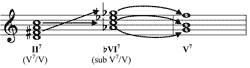

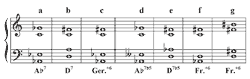

[7] The pitch-class invariance of tritone-related dominant sevenths and augmented sixths is shown in Example 6. The enharmonic respelling implicit in tritone substitution, of diminished fifth as augmented fourth or vice versa (Examples 6a and 6b), is the same as that between dominant seventh and augmented sixth (Examples 6a and 6c). Because the French augmented sixth maps onto itself at the transposition of a tritone, it can be interpreted as either of two dominant sevenths with flatted fifths whose roots are a tritone apart, and hence it functions as its own tritone substitute: examples d, e, f, and g all comprise the same pitch-classes.

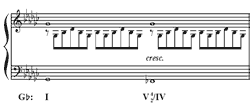

[8] In light of this relationship, augmented-sixth chords built on ![]() VI that resolve to the dominant can be reimagined as tritone substitutes for ii7 or V7/V. In

Example 1, replacing A

VI that resolve to the dominant can be reimagined as tritone substitutes for ii7 or V7/V. In

Example 1, replacing A![]() in the bass with either D or A

in the bass with either D or A![]() transforms the augmented sixth, enharmonically A

transforms the augmented sixth, enharmonically A![]() 7, into D7 (V7/V or V

7, into D7 (V7/V or V![]() /V).

Likewise, augmented sixths built on

/V).

Likewise, augmented sixths built on ![]() II that resolve directly to the tonic can be construed as tritone substitutes for V7. Both contain the dominant-functioning scale degrees

II that resolve directly to the tonic can be construed as tritone substitutes for V7. Both contain the dominant-functioning scale degrees

![]() and

and

![]() and can be viewed as altered forms of the diatonic dominant. In

Example 2, replacing the bass of the French sixth with either G or D

and can be viewed as altered forms of the diatonic dominant. In

Example 2, replacing the bass of the French sixth with either G or D![]() results in a diatonic V7.

results in a diatonic V7.

Commonalities

[9] Before examining the differences between these two chord classes, I will briefly survey their similarities. Both augmented-sixth chords and tritone substitutes serve as chromatic enhancements of diatonic chord functions, and are typically employed to approach cadences at points of formal articulation. Beyond enharmonic equivalence, two structural similarities are nonessential fifths, which in both cases may be omitted or altered without changing the harmonic function, and underdetermined roots: despite my reference to chord fifths, it remains a matter of debate whether augmented-sixth chords have roots at all or are purely linear chords,(6) while the tritone substitute has been described as a single altered dominant with two possible roots a tritone apart.(7)

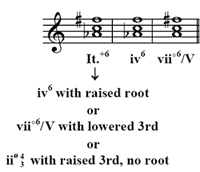

Example 7. Derivations of Augmented-Sixth Chords from Diatonic and Applied Harmonies

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[10] The problem of underdetermined roots, which augmented sixths share with diminished-seventh chords and—to a lesser extent—six-four chords, was recognized by Rameau, who asserted in 1760 that augmented-sixth chords had no fundamental bass and were uninvertible.(8) The difficulty in assigning roots to these chord types is demonstrated by their traditional textbook derivations from a variety of diatonic pre-dominants and applied dominants, as shown in

Example 7. Italian and German sixths can be explained as alterations of either iv(7), diminished

[11] The functional equivalence of augmented sixths to chords with roots a tritone away was recognized by a number of earlier theorists, including Rameau. Despite his claim in 1760 that augmented-sixth chords had no fundamental bass, in his final music treatise, published the same year, Rameau presented an example of a French sixth with a fundamental bass a diminished fifth below.(12) Similar examples were later offered by Kirnberger,(13) Sechter,(14) and Schoenberg.(15) Ernst Kurth came still closer to the idea of tritone substitution in assigning dominant function to chords built on ![]() II as well as V.(16)

II as well as V.(16)

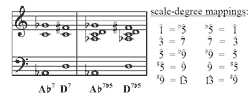

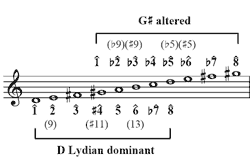

[12] The conception of an altered dominant chord as a dual-root dominant, with two possible roots a tritone apart, is strikingly similar. A series of tritone-related voicings of dominant chords that result in direct mappings of chord tones and chord extensions is shown in Example 8.(17) In each pair, the right-hand voicing is enharmonically respelled and the chord degrees are remapped as shown at right, but the pitch content of the upper structure remains constant. Within a tonal context, however, these chords do not have equal levels of harmonic intensity, because the substitution represents a chromatic intensification. In chord-scale theory, which treats chords and scales as vertical and horizontal expressions of the same pitch collection, tritone-related harmonies are associated with differing scales that imply different chord extensions and alterations.

[13] In Example 9, the scales on the left are derived from A melodic minor, and those on the right from E![]() melodic minor. The most common scale to play over a dominant chord is the Lydian dominant scale, shown below the staff. Lydian dominant is the fourth mode of melodic minor (i.e., a rotation of the melodic minor scale beginning on the 4th degree), and is equivalent to a major scale with raised

melodic minor. The most common scale to play over a dominant chord is the Lydian dominant scale, shown below the staff. Lydian dominant is the fourth mode of melodic minor (i.e., a rotation of the melodic minor scale beginning on the 4th degree), and is equivalent to a major scale with raised

![]() and lowered

and lowered

![]() . Typical chord extensions are the 9th,

. Typical chord extensions are the 9th,

![]() 11th (

11th (![]() 4th), and 13th (6th), any of which can be used in conjunction with the perfect 5th. The scale associated with the dominant chord a tritone away is the altered scale, also known as the diminished-whole tone or superlocrian scale. This scale, shown above the staff in

Example 9 (A

4th), and 13th (6th), any of which can be used in conjunction with the perfect 5th. The scale associated with the dominant chord a tritone away is the altered scale, also known as the diminished-whole tone or superlocrian scale. This scale, shown above the staff in

Example 9 (A![]() altered, which has 10 flats, is shown enharmonically as G

altered, which has 10 flats, is shown enharmonically as G![]() altered), is the seventh mode of melodic minor. Compared to the major scale, every degree is lowered except the root. Typical extensions are the

altered), is the seventh mode of melodic minor. Compared to the major scale, every degree is lowered except the root. Typical extensions are the ![]() 9th,

9th,

![]() 9th (or minor 3rd),

9th (or minor 3rd), ![]() 5th (

5th (![]() 11th or

11th or

![]() 4th), and

4th), and

![]() 5th (

5th (![]() 6th or

6th or ![]() 13th). The flat fourth in the scale functions enharmonically as a major third. Because the altered scale has both major and minor 3rds, two altered 5ths, and no perfect 5th, it is inherently less stable than the Lydian dominant scale. A tritone substitute is thus not merely an alternative harmony but a chromatic intensification, just as an augmented-sixth chord can be considered a chromatic intensification of a more diatonic pre-dominant.

13th). The flat fourth in the scale functions enharmonically as a major third. Because the altered scale has both major and minor 3rds, two altered 5ths, and no perfect 5th, it is inherently less stable than the Lydian dominant scale. A tritone substitute is thus not merely an alternative harmony but a chromatic intensification, just as an augmented-sixth chord can be considered a chromatic intensification of a more diatonic pre-dominant.

Differences

[14] One distinction between these two chord classes can be made on the basis of their perceived normative harmonic function. In music of the 18th and early 19th centuries, augmented sixths typically function as dominant preparations or elaborations, and in harmony textbooks this type is invariably privileged over the dominant-function type more common in the later 19th and 20th centuries. Tritone substitutes, in contrast, more typically replace a dominant or ii–V progression than a pre-dominant, although this distinction is blurred in jazz because of the preponderance of dominant chains, in which a dominant progresses to another dominant a fifth below. Jazz theory textbooks uniformly present the technique of tritone substitution as applying to dominant-function chords, and some even refer to “dominant substitution” rather than tritone substitution,(18) a term that implies the intermediary step of transforming a pre-dominant harmony into a dominant and then substituting it: for example, ii7→(II7 or V7/V)→![]() VI7.

VI7.

[15] A more notable difference between the two chord types lies in their conventional voice-leading procedures. The defining interval of an augmented-sixth chord requires resolution in contrary motion outward by semitone to an octave; more rarely, pre-dominant augmented sixths move down in parallel motion to dominant sevenths. In jazz, because the basic harmonic unit is not the triad but the seventh chord or other triadic extension, octave doublings are more rare (at least in piano and small-group voicings), and hence so are contrary-motion resolutions. In tritone substitutes that resolve to tonic harmonies, ![]()

![]() generally resolves down to

generally resolves down to ![]() , but

, but ![]() is equally likely to resolve up to

is equally likely to resolve up to ![]() , to move down to

, to move down to ![]() in an added-sixth chord, or to be held constant in a tonic major-seventh chord. Tritone substitutes that progress to dominants characteristically resolve downward by semitone in parallel motion.

in an added-sixth chord, or to be held constant in a tonic major-seventh chord. Tritone substitutes that progress to dominants characteristically resolve downward by semitone in parallel motion.

Example 10a. Tritone Substitutes as Augmented Sixths: Ellington, “In a Sentimental Mood,” ending

(click to enlarge)

Example 10b. Tritone Substitutes as Augmented Sixths: Ellington, “Mood Indigo,” end of second bridge

(click to enlarge)

Example 11. Augmented Sixth Resolving Down in Parallel: Beethoven Sonata Op. 57, 2nd movement, mm. 5–8

(click to enlarge)

Example 12. Augmented Sixth as Tritone Substitute: Mozart, Symphony No. 40, 2nd movement, mm. 66–67

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Example 13. Augmented 6th as Dominant 7th: Schubert, Impromptu Op. 90 No. 3, mm. 78–82

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[16] Two instances of tritone substitutes that are effectively recast as augmented sixths by their contrary-motion resolutions are shown in Examples 10a and b, both from Ellington songs. In the final cadence of “In a Sentimental Mood” (1935)(19) the dominant is replaced with a tritone substitute, labeled G![]() dominant seventh in the chord charts, but spelled as—and functioning as—a German sixth. Such contrary motion will result from any tritone substitution underneath leading-tone to tonic motion in the melody. Example 10b, from the end of the second bridge of Ellington’s “Mood Indigo” (1930),(20) is more unusual: a tritone substitute for ii, enharmonically E or F

dominant seventh in the chord charts, but spelled as—and functioning as—a German sixth. Such contrary motion will result from any tritone substitution underneath leading-tone to tonic motion in the melody. Example 10b, from the end of the second bridge of Ellington’s “Mood Indigo” (1930),(20) is more unusual: a tritone substitute for ii, enharmonically E or F![]() dominant seventh, functions as an inverted German sixth, in which a diminished third resolves inward to an octave on V7.

dominant seventh, functions as an inverted German sixth, in which a diminished third resolves inward to an octave on V7.

[17] While contrary motion defines an augmented-sixth chord, parallel motion does not necessarily define a tritone substitute.

Example 11 shows the end of the slow-movement theme from Beethoven’s Sonata Op. 57, the “Appassionata” (1804–5). At the end of measure 6, a German sixth (spelled with a doubly-augmented fourth) resolves down in parallel to V7, creating enharmonic parallel minor 7ths and perfect 5ths above the bass, which are only slightly mitigated by the 4-3 suspension in the topmost voice. Apart from the downward resolution of G![]() to G

to G![]() , however, there is no reason to interpret this passage as a tritone

substitution.

, however, there is no reason to interpret this passage as a tritone

substitution.

[18] A more compelling case for an augmented sixth as a tritone substitute

can be made when it replaces an expected bass motion by fifth with one by semitone, as in

Example 12, from the slow movement of Mozart’s Symphony No. 40 in G minor (1788), near the end of the development section. On beat 3 of the second measure (measure 67), the enharmonic reinterpretation of B![]() dominant seventh, V7/

dominant seventh, V7/![]() III, as an Italian sixth that moves down in parallel to A dominant seventh, V7/ii, abbreviates the progression by one chord: E

III, as an Italian sixth that moves down in parallel to A dominant seventh, V7/ii, abbreviates the progression by one chord: E![]() , or V/

, or V/![]() VI, is omitted from the cycle of fifths, which would normally proceed C–F–B

VI, is omitted from the cycle of fifths, which would normally proceed C–F–B![]() –E

–E![]() –A

–A![]() –D–G–C.

This truncation allows an expansion of the dominant by exactly one bar of the

–D–G–C.

This truncation allows an expansion of the dominant by exactly one bar of the

meter. Some other examples of tritone substitutes in art music are the final cadence of Schubert’s “Der Doppelgänger,” the opening of Liszt’s Piano Concerto No. 2, a passage from Liszt’s

Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen,(21) a passage from the middle section of Debussy’s “Pour Les Sixtes,”(22) and the retransition of the first movement of Ravel’s String Quartet in F major.(23)

meter. Some other examples of tritone substitutes in art music are the final cadence of Schubert’s “Der Doppelgänger,” the opening of Liszt’s Piano Concerto No. 2, a passage from Liszt’s

Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen,(21) a passage from the middle section of Debussy’s “Pour Les Sixtes,”(22) and the retransition of the first movement of Ravel’s String Quartet in F major.(23)

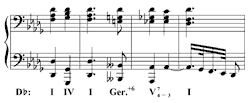

[19] A more rarefied distinction can be made on the basis of larger-scale enharmonic reinterpretations. In 19th-century music, a common modulation by semitone pivots on the literal reinterpretation of dominant sevenths and augmented sixths with the same root, a relationship described by Vogler and Gottfried Weber as a type of

Mehrdeutigkeit, or multiple meaning.(24) Most typically, an augmented sixth is reinterpreted as V7 of the Neapolitan, as in

Example 13, which occurs near the end of Schubert’s G![]() Impromptu, Op. 90 No. 3 (1827). The second halves of measure 79 and measure 80 are enharmonically equivalent, but the first is resolved as a dominant seventh, to G minor, the second as an augmented sixth re-establishing the tonic, G

Impromptu, Op. 90 No. 3 (1827). The second halves of measure 79 and measure 80 are enharmonically equivalent, but the first is resolved as a dominant seventh, to G minor, the second as an augmented sixth re-establishing the tonic, G![]() major.

major.

[20] In jazz, the converse is customary: enharmonic pivots effecting a modulation are rare, but tritone-related dominants may be used to approach a common resolution. Such an extension of dominant function through dual roots occurs at the end of the A section in Rezso Seress’ “Gloomy Sunday” (1933), shown in

Example 14. As in the tritone-related voicings

shown in example 8, the dominant occurs over both ![]() and

and ![]()

![]() as roots. A similar example occurs in the retransition of the first movement of Debussy’s String Quartet.(25) The dual-root relationship is expressed on a larger scale at various points in Gershwin’s

Rhapsody in Blue; an instance immediately preceding the second theme is shown in

Example 15. Between two statements of a modified omnibus progression on the local dominant (B), another statement of the same progression a tritone away (on F) is interpolated. Both progressions are resolved with the entrance of the second theme on E.

as roots. A similar example occurs in the retransition of the first movement of Debussy’s String Quartet.(25) The dual-root relationship is expressed on a larger scale at various points in Gershwin’s

Rhapsody in Blue; an instance immediately preceding the second theme is shown in

Example 15. Between two statements of a modified omnibus progression on the local dominant (B), another statement of the same progression a tritone away (on F) is interpolated. Both progressions are resolved with the entrance of the second theme on E.

|

Example 14. Dual-Root Dominant: Seress, “Gloomy Sunday,” end of A section (click to enlarge and see the rest) |

Example 15. Dual-Root Dominant Expansion: Gershwin, Rhapsody in Blue, bridge to second theme (click to enlarge) |

Conclusion

[21] Augmented-sixth chords and tritone substitutes share a number of structural features, including pitch-class content, nonessential fifths, underdetermined roots, structural position, and two possible harmonic functions, as pre-dominant or dominant. A significant distinction between these two chord classes can be made, however, on the basis of their behaviors: they differ in their voice-leading conventions of contrary vs. parallel, normative harmonic function as dominant preparation vs. dominant substitute, and enharmonic reinterpretation as modulatory pivot vs. dual-root dominant approaching a common resolution. While the correlation between these two chord classes has been described as a point of intersection between jazz and classical theoretical orientations, the differences described above allow us to identify augmented-sixth chords in jazz as well as classical repertoires, and tritone substitutes in classical as well as jazz. Such distinctions help clarify our understanding of these chords and their linear, harmonic, and tonal functions.

Nicole Biamonte

University of Iowa

School of Music

1006 Voxman Music Building

Iowa City, IA 52242

nicole-biamonte@uiowa.edu

Footnotes

1. Published discussions of this topic consist of a summary

of tritone substitution in Ramon Satyendra, “Analyzing the Unity within

Contrast: Chick Corea’s ‘Starlight’,” in Engaging Music, ed. Deborah Stein

(Oxford University Press, 2005), 55; a brief article by William L. Fowler, “How

to Americanize European Augmented Sixth Chords,” Down Beat 47, Jan. 1980: 64–65

and Feb. 1980: 66; and several online jazz and popular music forums, including

Andy Milne, “The Tonal Centre,” <http://www.andymilne.dial.pipex.com/Discords.shtml>.

Recent classical-theory textbooks that include both augmented-sixth chords and

tritone substitutes include Robert Gauldin, Harmonic Practice in Tonal Music,

2nd ed. (Norton, 2004), 546–47; Deborah Jamini, Harmony and Composition: Basics

to Intermediate (Trafford, 2005), 448; and Fred Lehrdahl, Tonal Pitch Space,

(Oxford University Press, 2001), 311; a recent jazz-theory textbook is Kurt

Johann Ellenberger, Materials and Concepts in Jazz Improvisation (Assayer,

2005), 97ff. and 191ff. Miguel Roig-Francolí, Harmony in Context (McGraw-Hill,

2003), 671–72, includes an explanation of the tritone substitute in his

discussion of the Neapolitan as a substitute for V.

Return to text

2. Daniel Harrison, “Supplement to the Theory of

Augmented-Sixth Chords,” Music Theory Spectrum 17/2 (1995): 174–76 and 187; for

a discussion of these resolutions see also Richard Bass, “Enharmonic Position

Finding and the Resolution of Seventh Chords in Chromatic Music,” Music Theory

Spectrum 29/1 (2007): 81–83.

Return to text

3. Arrangement published by Tempo Music, 1953. The Real Book 6th edition changes are | Am7–D7 | A![]() m7–D

m7–D![]() 7 | CΔ7 |.

7 | CΔ7 |.

Return to text

4. Originally written for St. Louis Woman; arrangement pubished by A-M Music Corp., 1946; repr. Hal Leonard, 1991.

Return to text

5. Robert D. Morris, Class Notes for Atonal Theory (Frog

Peak Music, 1991), 58–61.

Return to text

6. For a survey of historical and contemporary views

regarding the rootedness or rootlessness of augmented-sixth chords, see

Harrison, “Supplement to the Theory of Augmented Sixth Chords,” 171–72 n3, and

Graham Phipps, “The Tritone as an Equivalency,” Journal of Musicology 4/1

(1985–6): 51–69.

Return to text

7. Mark Boling, The Jazz Theory Workbook, 2nd ed. (Advance

Music, 1993), 81–82; Dan Haerle, The Jazz Language (Warner Bros., 1980), 39; and

Andy Jaffe, Jazz Harmony, 2nd ed. (Advance Music, 1996), 73.

Return to text

8. Jean-Philippe Rameau, Lettre à M. D’Alembert sur ses

opinions en musique (Paris: L’imprimerie royale, 1760; repr. Broude Bros.,

1965). See Jonathan Bernard, “The Principle and the Elements: Rameau’s

‘Controversy with d’Alembert,’” Journal of Music Theory 24/1 (1980): 53–54.

Return to text

9. Friedrich Wilhelm Marpurg, Handbuch bey dem Generalbasse

und der Composition (Berlin: J. J. S. Wittwe, 1755), 125–27; and “Untersuchung

der sorgischen Lehre von der Entstehung der dissonierenden Sätze,” in

Historisch-Kritische Beyträge zur Aufnahme der Musik, vol. 5 (Berlin: J. J.

Schützens, 1761), 167–68.

Return to text

10. Georg Joseph Vogler, Handbuch der Harmonielehre

(Prague: K. Barth, 1802), 101–110; and Gottfried Weber, Versuch einer geordneten

Theorie der Tonsetzkunst (Mainz, 3rd ed., 1830–32), v. 1, 259–60.

Return to text

11. Ralph Turek, Theory for Today’s Musician (McGraw-Hill,

2007), 458; Thomas Benjamin, Michael Horvit, and Robert Nelson, Techniques and

Materials of Music, 6th ed. (Wadsworth, 2003), 155; Robert Ottman, Advanced

Harmony, 4th ed. (Prentice Hall, 1992), 247; and Walter Piston and Mark DeVoto,

Harmony, 5th ed. (W. W. Norton, 1987), 420.

Return to text

12. Jean-Philippe Rameau, Code de musique pratique (Paris:

L’imprimerie royale, 1760), example booklet, 4, ex. L #2; see also 15, ex. K #8

and 18, ex. N. David Kopp describes this approach as making “surprising

transformational sense.” See David Kopp, Chromatic Transformations in

Nineteenth-Century Music (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 181.

Return to text

13. Johann Philipp Kirnberger, “The True Principles for

the Practice of Harmony” (Die wahren Grundsätze zum Gebrauch der Harmonie,

1773), trans. David Beach and Jurgen Thym,

Journal of Music Theory 23/2 (1979): 186–88.

Return to text

14. Simon Sechter, Die Grundsätze der musikalischen

Komposition, v. 1 (Leipzig: Breitkopf and Härtel, 1853), 147, 186, and 215–16.

Return to text

15. Arnold Schoenberg, Theory of Harmony (Harmonielehre,

1922), trans. Roy E. Carter (Berkeley: University of California, 1978), 115–25,

193, and 245–56.

Return to text

16. Ernst Kurth, Romantische Harmonik und ihre Krise in

Wagners Tristan (Berlin: Hesse, 1920), 60.

Return to text

17. Common dominant voicings that do not map onto themselves at the

transposition of a tritone are dominant sevenths with

![]() 5,

5, ![]() 9

9![]() 5, 9, 9

5, 9, 9![]() 5,

5,

![]() 9, alt

(

9, alt

(![]() 9

9![]() 9

9![]() 5

5![]() 5), 13, 13

5), 13, 13![]() 9, and 6/9. For clarity, I have

used the correct spellings for all chord extensions, but in practice

the enharmonic pitches would be written more simply (D instead of

9, and 6/9. For clarity, I have

used the correct spellings for all chord extensions, but in practice

the enharmonic pitches would be written more simply (D instead of ![]()

![]()

Return to text

18. Peter Spitzer, The Jazz Theory Handbook (Mel Bay,

2001), 36, and Andrew Jaffe, Jazz Harmony, 67–71.

Return to text

19. American Academy of Music, 1935; repr. Belwin Mills,

1973.

Return to text

20. Mills Music, 1931; repr. Belwin Mills, 1973. In this

arrangement and in the Real Book, this chord is labeled E7.

Return to text

21. See Harrison, “Supplement to the Theory of Augmented

Sixth Chords,” 187–88.

Return to text

22. See William E. Benjamin, “‘Pour les Sixtes’: An

Analysis,” Journal of Music

Theory 22/2 (1978): 271.

Return to text

23. See Phipps, “The Tritone as an Equivalency,” 58.

Return to text

24. Vogler’s first species of Mehrdeutigkeit included the

enharmonic equivalence of German sixths to dominant sevenths and that of French

sixths to two dominant sevenths with flatted fifths a tritone apart. See Vogler,

Handbuch zur Harmonielehre (Prague: K. Barth, 1802), 101–10. Weber considers

the possibilities for enharmonic reinterpretation of an augmented sixth as a

dominant seventh in his Versuch einer geordneten Theorie der Tonsetzkunst (Mainz: B. Schott, 1830), 255–69.

Return to text

25. See Phipps, “The Tritone as an Equivalency,” 58. Other

explorations of tritone equivalencies are Erno Lendvai, Symmetries of Music (Kodaly

Institute, 1993), and Wolfgang Loffler, “Vom Tritonus und anderen teuflischen

Klangen,” in Jazz und Avantgarde, ed. Jurgen Arndt and Werner Keil (Olms, 1998),

222–37. In this essay, I am concerned primarily with tritone-related sonorities

that function more or less conventionally in a tonal context. A fuller

consideration of tritone relations, including those employed for programmatic

effect, within minor-third cycles, as expressions of octatonicism, or in

post-tonal repertoires, is beyond the scope of this study.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2008 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason, Managing Editor and Mitch Ohriner, Cara Stroud, and Tahirih Motazedian, Editorial Assistants

Number of visits: