Sonata-Formal Functions and Transformational Processes in the First Movement of Rochberg’s String Quartet No. 6 *

Mustafa Bor

KEYWORDS: transformational theory, Rochberg, form, sonata, transposition, K-nets, inversional balance, animation

ABSTRACT: To the extent that it represents the actual temporal event-series of a composition, transformational theory can reveal some interesting correlations between the formal functions of sections and the transformations that characterize them. For example, the changes in characteristic transformations in the first movement of George Rochberg’s sixth string quartet articulate specific functions familiar in sonata form. The differing types of transformations (transposition versus inversion) in the first two sections set up a contrast analogous to that of the first and second themes. The third section functions as a development section, blending both types of transformations found in the exposition. Reprises of these types, and their contrast, define the function of the last two sections as a recapitulation, in which the second-theme group is metaphorically transposed. Rochberg has been criticized for mimicking conventional musical structures, but this analysis demonstrates how he successfully reinvents a tonal form with non-tonal transformations.

Copyright © 2009 Society for Music Theory

[1] Published analyses employing networks of musical transformations have been critiqued for concentrating more on relatively small-scale processes and relations—chord progressions and motivic transformations—than on large-scale form and for omitting the chronological flow of the music which they represent (Morris 1995, Cook 1996). There are some notable exceptions to this trend, such as the last chapter of Lewin (1993) and Cohn (1999). Usually we understand the formal functions of large groups to depend, among other things, on the chronological order in which they are presented. The selection of a particular spatial layout in constructing a network is, in essence, the selection of the musical features that the network can model. Thus, if we want to discuss form in the temporal sense that it is conventionally understood, it is important that the network represents the temporal order of the piece’s events.

[2] However, Lewin’s discussions of transformational form are often essentially atemporal. For example, his analysis of Dallapiccola’s Simbolo (the first chapter of Lewin 1993) identifies a bi-partite form whose two parts resemble each other, but this resemblance is defined purely in terms of transformational networks that are arranged anachronically. Similarly, his analysis of Stockhausen’s Klavierstück III (the second chapter of Lewin 1993) sets aside a temporally ordered network, along with its “phenomenological presence” (Lewin 1993, 32), in favor of a spatial network that does not depict “how the piece moves through chronological time” (Lewin 1993, 17). Lewin presents a series of four different passes through the spatial network as a narrative account of the piece, but these passes do not by themselves represent sections of a form, standing instead as supplements to the atemporal spatial network. The last chapter of Lewin (1993) attempts to address a long composition and the interaction of its form with transformational structuring. This is similar to the work of Cohn (1999), which represents a large (sonata) form with transformational networks. Neither of the authors, however, discusses thematic aspects of non-tonal form in ways that are analogous to traditional accounts, such as the distinctions commonly made, say, between the types of material that characterize principal themes, secondary themes, and developments. Since “formal functionality involves the way in which music expresses its logical location in a temporal spectrum” (Caplin 1998, 111), such distinctions are essentially temporal, notwithstanding idiosyncrasies, such as a theme beginning with a continuation function;(1) they are perceived through hearing the themes in order and hearing the themes’ inner groups, which fulfill specifically temporal functions.

[3] Nothing in transformational theory prevents making such temporally consequential distinctions. Indeed, transformational theory suggests a potentially powerful way to make them—by describing and contrasting not only sections’ content but also their characteristic transformations. From this point of view the difference between a first theme and a second theme, particularly in non-tonal music, would not only be in their pitches, melodic contour, intervallic content, and durations, but also in the internal transformations they manifest.(2) Some interesting questions arise in such an approach: can the introduction of new transformations, even when not introducing new materials, signal different sections, and can the reprise of specific transformations articulate the recapitulation of sections of similar formal function? If so, it might be possible to give convincing transformational-network accounts of form in large-scale non-tonal pieces.

[4] In this paper, I show how to hear changes in transformations in the first movement of George Rochberg’s sixth string quartet as articulating specific formal functions, in the sense of William Caplin’s theory of form in the Classical style (Caplin 1998). Caplin’s theory of “formal functions” is in many ways a reworking and extension of the formal theories introduced by Arnold Schoenberg (1967) and Erwin Ratz (1973). The common ground between all three is a shift of focus from “what” the formal parts are to “how” these parts function as presentation, continuation, or cadential section. Of course, Caplin shows how processes of harmonic tonality articulate and characterize these functions, but the notion of formal functions is suggestive for a wider range of repertoire.

[5] The last of the “Concord” series, the Sixth Quartet is typical of Rochberg’s post-1963 works, which blend tonal and post-tonal idioms to achieve “maximum variety of gesture and texture and the broadest possible spectrum

[6] Let us begin with a top-down overview of the grouping structure of the movement. As I hear it, the movement can be divided into five sections on the basis of contrasts presented in various parameters, such as tempo, dynamics, bowing, and texture. For example, the change from the first section to the second is marked by a clear texture shift from homophony to monophony/polyphony, as well as by a change in tempo. The other sectional divisions are also mostly marked by tempo and/or textural changes. These sections are stratified texturally into what I will call “layers.” Each layer is distinct from others in pitch, contour, texture, rhythm, and timbre. For instance, the descending leap pattern of violin 1 in measures 1–2, which begins the first layer, is very different from the repeated chords in the other instruments in measures 3–4, which begin the second layer (the score is displayed in Animation 1a and discussed in paragraph [10]). The differentiation is not limited to the textures but also includes the durations and overall registers of these layers. Within each layer, there are a number of motivic units, each of which is generally repeated in a pitch–altered form, but maintains the distinctive qualities mentioned above. For example, the repetition of the first unit in measure 5 is basically a transposition of the same unit presented in measures 1–2 (see Example 1, Layer 1 in paragraph [10]).

[7] From the bottom up, the grouping hierarchy of the movement is composed as follows: units constitute the layers, the layers combine concurrently and sequentially to constitute the sections, and the sections combine sequentially to constitute the entire form. Except for the rather free way in which the layers combine, the scheme certainly alludes to the organization of classical-form movements. This is reflected in the following examples, each of which denotes a particular section. They inventory the sections’ layers, denoting each by an Arabic numeral, and the layers’ respective units, denoting each alphabetically. When a particular unit within a layer recurs with some variation, I distinguish its instances by labeling them with different letters. I often focus on how the pitch structure of units changes from one instance of the unit to another. I treat these changes as transformations (of pitch-classes or pitches) and consider how they relate to other transformations that take place in the same section, as well as to transformations in the other sections.

[8] Animations 1–5 provide a visual and aural aid to demonstrate the proposed ideas more vividly. Each analysis is presented first by an animation on the musical score, synchronized with a recording, and then silently on a two-dimensional grid of pitches. The grid is organized in one dimension by the transposition T4 and in the other by T5, thus forming a Tonnetz. These specific transpositions are, in fact, the defining transformations of the first section. The Tonnetz representations demonstrate how different transformations employed throughout the movement share a certain quality, namely a characteristic move of pitch-class collections, which is effectively displayed by the T4-T5 grid.(3) The different layers in the examples are shown in different colors in the presentation.

[9] Some notes that appear in the score are not included in the analysis. There are two fundamental reasons for such omission. In some instances, notes are excluded because of their accompanimental or ornamental nature. For example, the viola and cello parts in measure 1 and the violin 2 and cello parts in measure 5 (see Animation 1a in paragraph [10]) accompany the motivic gesture presented by violin 1, which holds a prominent role in the movement. In other instances, the notes

that constitute a more integral part of the work do not contribute to the analytical argument made in that particular context. For example, two pitches, ![]() 4

4![]() 4

4

Animation 1a

(click to view the animation)

Animation 1b

(click to view the animation)

Example 1. Exposition, 1st theme group, measures 1–17 (3 layers)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[10] The first section is analyzed by Animations 1a and 1b, and Example 1. It consists of three distinct layers, each clearly distinguished from the others in terms of its texture, length, rhythm and intervallic content. The units of Layer 1 all consist of a sixteenth-note m9 descent plus a long sustained note, forming a 012 trichord. These pitch classes (pcs) are accompanied by a few others that do not figure in the transformational analysis. Layer 2 presents various vertical trichords and tetrachords. Layer 3 consists of adjacent groups of 0236-type tetrachords, mostly in thirty-second notes; however, a few of the tetrachords are incomplete. Animation 1a shows how these layers proceed in real time, distinguishing them by colors. Examples 1 and 2 are labeled as “Exposition” for reasons explained later in the article.

[11] Example 1 diagrams the layers more abstractly, as temporally ordered networks, in order to clarify the transformations that characterize them, which are also shown in Animation 1a. In Layer 1, the first unit, labeled a, is transformed by T8 to the second unit, b. The third unit of this layer is identical to a, and can be heard as T4 of b as well. The fourth unit is identical to b, and so it can be heard similarly as T8 of the preceding unit.

[12] Layer 2 involves a somewhat different transformational process. Its first three units,

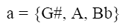

labeled c, d, and e, all hold the two pcs {A, ![]()

[13] The last layer, 3, does not begin until after the second statement of a Layer 1 unit, but thereafter it recurs regularly along with the other layers. This layer is different from the other two layers in its hierarchical structure, which involves two levels of transposition: the lower level of T7 and the higher level of T4. In this layer, not all units are transformed or are the results of transformations. For example, units i and k are not transformed to obtain other units and units g′ and j are not obtained by transformations of other units. It is interesting to note that the return to g in measure 14 involves a pitch variation and thus is labeled as g′. The first three notes of the four-note collection of g are transposed by 2 semitones in g′. However, the rest of the sequence is a perfect reprise of the opening units of g, h, and i.

[14] Animation 1b shows three pitch grids. They differ in content, but each is organized by T5 in one dimension and by T4 in the other, and they show the transformational actions on pcs in one of the layers of the first section. In the first layer (the leftmost grid), the units are expressed by a distinctive slanted rectangle that encloses chromatically related pcs, since T7,T4= T11. As the animation proceeds, the movements of this rectangle to the left, then right, then left again, represents the series of transpositions evident in Layer 1 of Example 1. At the same time, over on the rightmost grid, representing Layer 3, a slanted T shape moves upward twice, then shifts down and to the right, and then repeats two upward moves. These moves express the transpositions from unit to unit, and from unit-group to unit-group, in Layer 3 of Example 1. The motion on the central grid deforms the rectangle in various ways, conforming to how the individual pcs are transposed in Layer 2. Altogether it is evident that T4, T5, and their inverses are strongly characteristic of this passage.

[15] The first section has certain features that are significant for the large-scale form of the movement. Although the layers differ in content, the transformations that characterize them are all of one type, namely, transposition. Furthermore, the overall structure of the section presents a sort of antecedent-consequent pair, as is evident from the recurrence of the incipit pairs a-b in measures 9–10 and 13, respectively. This formal structure is further supported by the recurrence of the third layer units g′-h-i in measure 14.

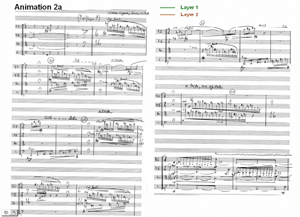

Animation 2a

(click to view the animation)

Animation 2b

(click to view the animation)

Example 2. Exposition, 2nd theme group, measures 18–35 (2 layers)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[16] The second section presents two distinct layers, both of which involve small changes of pitch that could be heard as linear motion. In the manner of the discussion above, it is analyzed in Animation 2a, which shows the layers on the score appearing in synchronization with a recording, together with the transformations within them. Example 2 represents each entire layer by a temporally ordered transformational network, and Animation 2b realizes Layer 2 on the T5/T4 pitch grid.

[17] The first layer is presented by five pairs of units that alter their pitch but maintain a consistent transformational structure that can be expressed by trichordal Klumpenhouwer networks. The second layer, as shown by the arrows in Example 2, consists of various units whose pitches are inversionally balanced. In other words, as each unit unfolds, each pitch in the second half is the inversion, around a virtual pitch-center of inversion, of the retrograde-corresponding pitch in the first half. That is, the second half is a retrograde pitch-inversion of the first half. I will refer to the inversional center as the “inversional balance pitch,” or IBP; it differs for each unit. Of course, inversional processes may occur among pitch classes, too, and I will refer to the corresponding centers as IBPCs.

[18] Animation 2b makes the processes of Layer 2 strikingly apparent on the pitch-class T5/T4 grid. First a thick circle appears around the first IBPC, C. Then all the notes of the first unit appear circled as pairs arranged symmetrically around C. All pcs adjacent to C appear, plus two pcs that are two steps from the center vertically on either side. Then the IBPC indicator shifts up and left to ![]()

[19] Although the T5/T4 grid seems well suited to represent both the first section and the second section, the animations actually help to underscore a significant difference. Both layers in the second section are characterized by the use of inversion, in contrast with the transpositionally oriented first section.

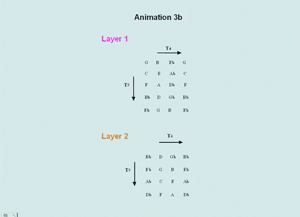

[20] The third section consists of three layers. They are identified and analyzed, as in the previous sections, by two movies, Animation 3a and 3b, and by the fixed but temporally ordered transformational networks in Example 3. In this section no new types of transformations are introduced; all transformations are drawn from the previous two sections. Consider the first layer, shown at the top of Example 3. It presents inversionally balanced pitch groups, like those in the second layer of the second section. What is different, however, is the way these transformations are represented. In the second section, the inversional balance points are established by retrograde-inversional melodic motion. However, in the third section, they are the centers of accelerating trills whose timbre and dynamics are distinctive. But we can also easily perceive the transpositions that transform one balance point to another, shown as labels on the arrows connecting the nodes. Therefore, the first layer of the third section combines the two types of transformations, transposition and inversion, that respectively characterized the first and second sections.

|

Animation 3a (click to view the animation) |

Animation 3b (click to view the animation) |

Example 3. Exposition, measures 36–51 (3 layers)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Animation 4

(click to view animation)

Example 4. Recapitulation, 1st theme group, measures 52–74 (1 layer)

(click to enlarge)

Animation 5a

(click to view animation)

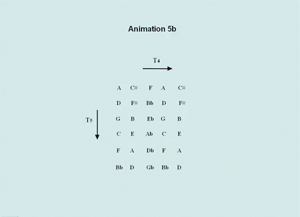

Animation 5b

(click to view animation)

Example 5. Exposition, measures 36–51 (3 layers)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Figure 1. Formal scheme of the movement

(click to enlarge)

[21] Layer 2 is not as unique as Layer 1. The analysis of it in Example 3 clearly shows it to be a variation of Layer 2 of the second section. Animation 3b displays the inversional balancing process in Layers 1 and 2. Example 3 also shows the third layer to be a more complex version of the first layer of the second section, taking the trichordal K-nets and expanding them to tetrachordal K-nets. Apparently, the overall characteristic of this third section is one based on conflicts between the first and second layers. I perceive the alternation between the static, insistent nature of the first layer and the fluid, slippery nature of the second layer to create a kind of tension. The combination of this tension with the reprise and mixture of transformational processes from the first two sections makes the third section seem like the development in a sonata form.

[22] If such a formal process is indeed operative here, we would expect to hear a recapitulation next. So let us examine the following passage, represented in Animation 4 and Example 4. In some respects this seems to continue and cadence the preceding music, but its length and uniformity are so substantial that I hear it assuming its own thematic presence. In fact, it can be understood as a reprise of the first section, but only partially, replaying just the first unit of the first section in a more purified, simpler way. The smooth diminuendo from fortissimo to pianissimo makes this fourth section more continuous than the first section, which had many sudden dynamic changes. Although this section does not contain any transformations, Animation 4 is provided for the listener to observe the effect of the repetitive opening unit. In fact, such an effect might lead one to hear this section as a retransition or standing on the dominant.(4) While one could also conceive the possibility of the formal functions of recapitulation and retransition being conflated to a certain degree in this passage, the recurrence of the exposition’s opening unit exerts a rather strong presence.

[23] Similarly, the last section, presented in Animation 5a and analyzed in Example 5, reprises only the second layer of the second section. This reprise is not exact either: the inversional balance pitch–classes are different from those in the second section. Nevertheless, they are related, as clarified by Animation 5b, which shows the three IBPCs of the second section shifting to the three IBPCs of the last section by T2 (that is, by two inverse-T5 steps on the grid).

[24] The end of Animation 5a exhibits the persistent repetition of a dissonant chord presenting a gradual diminuendo from ff to ppp. If this chord is understood to continue the preceding music, then we can hear this whole passage as suggesting closure for the movement, because it completes nearly the entire aggregate. The one missing pitch-class, D, has a unique role in the whole string quartet, consideration of which is beyond the scope of this paper. Suffice it to say that in the second movement of the quartet, D is the only root missing from a near-aggregate of triads. The entire third movement is a set of variations on the Pachelbel Canon in D, compensating for the missing D in the previous movements.

[25] The analysis of form in Examples 1–5 has shown that sections have fairly clear transformational similarities and differences that support the sonata-rhetoric: the first section is characterized by transposition, the second section contrastingly by inversion, and the third section by a combination of both. Although the fourth section lacks transformation due to its simplicity, the formal connection with the first section is clearly provided by the main unit or motive of the first section. Lastly, the fifth section reiterates the second section. Figure 1 clarifies the similarities between this five-section scheme and sonata-allegro form: these similarities can be expressed in the terminology William Caplin uses to discuss this form in Classical music.

[26] The first section has a deliberate affect that we realize retrospectively when we hear the second section. But this quality also arises from its internal structure. We have seen that it presents an antecedent-consequent pair. In addition, it involves transposition within units, which is similar to the transposition of a basic idea within a sentence. The combination of procedures characteristic of both period and sentence does seem to evoke a tight-knit thematic quality characteristic of a prototypical first-theme group.

[27] The second section functions as a “looser” second-theme group, not only because of its flowing character, as opposed to the more stable character of the first-theme group, but also because of the shift to more abstract inversional transformational processes, which includes K-nets and inversionally balanced pitch groups. Here the contrast between the types of transformations (transposition versus inversion) is analogous to the contrast of first- and second-theme materials that is characteristic of classical sonata form.

[28] Caplin emphasizes two aspects of development in sonata form: “as a formal unit, a development stands between an exposition and a recapitulation; [and] as a formal function, a development generates the greatest degree of

[29] The fourth and fifth sections draw their materials and transformations from the first and second sections, respectively. The formal functions of this repetition are identical to those in the first- and second-theme recapitulations in sonata-allegro form. The specific relations of these sections to the earlier ones also mimic those in sonata form: the fourth section reprises first-section materials at their original transposition level, while the fifth section presents a transposition of the second section materials. Thus, the fourth and fifth sections clearly function as recapitulation, where the first-theme group is simplified such that only the main motive is presented, and the second-theme group is transposed, alluding to similar procedures in sonata form.

[30] In this paper I advocate hearing non-tonal pitch transformations as formative features of this movement. Of course, one must remain cautious in such an interpretation of a non-tonal piece, since the classical theories of form are heavily based on tonal phenomena. Yet, the movement’s unmistakable resemblances to conventional sonata form provoke an analogy based on other sectional characteristics where keys, tonics, and roots are absent. One such characteristic of sections—that is, their transformational network-structure—has the potential to reveal the formal functions of the relevant sections. Such an approach seems to be fruitful in the light of the analysis presented, which demonstrates how Rochberg, who is often criticized for imitating traditional musical structures, successfully reinvents sonata form with non-tonal transformations.

Mustafa Bor

Department of Music

University of Alberta

Edmonton, AB

T6G 2C9 CANADA

mbor@ualberta.ca

Works Cited

Caplin, William E. 1998. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. New York: Oxford University Press.

http://www.grovemusic.com (Accessed May 08, 2007).

Clarkson, Austin and Steven Johnson. 2001. “Rochberg, George.” In Grove Music Online. Ed. Laura Macy.

http://www.grovemusic.com (Accessed May 08, 2007).

Cohn, Richard L. 1999. “As Wonderful as Star Clusters: Instruments for Gazing at Tonality in Schubert.” Nineteenth-Century Music 22/3: 213–32.

Cook, Nicholas. 1996. Review of Musical Form and Transformation: 4 Analytic Essays, by David Lewin. Music & Letters 77/1: 143–46.

Lewin, David. 1987. Generalized Musical Intervals and Transformations. New Haven: Yale University Press.

—————. 1993. Musical Form and Transformation: 4 Analytic Essays. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Morris, Robert D. 1995. Review of Musical Form and Transformation: 4 Analytic Essays, by David Lewin. Journal of Music Theory 39/2: 342–83.

Ratz, Erwin. 1973. Einführung in die musikalische Formenlehre: Über Formprinzipien in den Inventionen und Fugen J. S. Bachs und ihre Bedeutung für die Kompositionstechnik Beethovens. Vienna: Universal Edition.

Schoenberg, Arnold. 1967. Fundamentals of Musical Composition. Ed. Gerald Strang and Leonard Stein. London: Faber & Faber.

Footnotes

* This is a revised version of a paper presented at the 2006 annual meetings of the Rocky Mountain Society for Music Theory in Denver, Colorado, and the Music Theory Midwest in Muncie, Indiana. I thank John Roeder for his encouragement and advice during the writing of this paper.

Return to text

1. Caplin uses the term formal dissonance to describe instances in which “a given function is actually placed differently from its expressed temporal position” (111).

Return to text

2. Haydn’s monothematic sonata forms provide a tonal example of formal function encoded by transformational relationship between the first and second themes (tonic-dominant) rather than the content itself. However, in monothematic sonata forms the transformation takes place between the themes rather than within the themes. The approach adopted in this paper examines the internal transformations in the formal sections and compares and contrasts them from a formal-functional point of view.

Return to text

3. Although it is possible to assert a quasi-tonal reading of the movement based on this tonal network established upon T4 and T5, I will not pursue this line of thought in the present study.

Return to text

4. It should be noted that Caplin draws a distinction between “retransition” and “standing on the dominant” indicating that “if the term retransition is to be used with most development sections, it should be applied before the standing on the dominant, presumably at the moment when the modulation to the home key takes place” since “by the time the standing on dominant begins, the home key has already been achieved” (157). Thus, the fourth section should be understood to function as a standing on the dominant rather than a retransition as a result of the recurrence of the opening unit.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2009 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by William Guerin, Cara Stroud, and Tahirih Motazedian, Editorial Assistants

Number of visits: