An Interactive Trichord Space Based on Measures 18–23 of Clermont Pépin’s Toccate no. 3

Stephanie Lind

KEYWORDS: Pépin, transformational theory, motivic repetition and development, transformational theory, Québécois composers, Canada

ABSTRACT: Clermont Pépin’s Toccate no. 3, a work for piano composed in 1961, features extensive repetition and sequencing through the development of smaller atonal intervallic motives. Measures 18–23, in particular, manifest several elements that return repeatedly in the course of the work, and consequently a space defined by the objects and transformations characteristic of this passage can provide a framework for interpreting transformational relations throughout the piece. This paper provides such a space, in an interactive format that allows the reader to explore grouping structure within the passage. The space is then expanded to accommodate later passages involving similar motivic material.

Copyright © 2009 Society for Music Theory

Introduction

[1.1] Clermont Pépin (1926–2006), a prolific and influential twentieth-century Canadian composer, incorporates elements from serialism, jazz, and neo-classicism, but like many Québécois composers of his generation also employs the repetition and development of smaller atonal intervallic motives. By interpreting these intervallic motives transformationally (that is, understanding them as a series of transformations rather than as a grouping of pitch classes), motivic repetition can be depicted as a series of moves through a space. The structure of the space, its objects and transformations, and the path through the space all express characteristic elements of the associated musical passage.

[1.2] The analysis presented in this paper will examine one such case of motivic development in the Toccate no. 3, a work for piano composed in 1961. In this piece, the right and left hands of the pianist present two independent but interactive melodic voices. Recurring intervallic motives are commonly heard, as are exact- and near-sequences. Measures 18–23 of the work, in particular, present all of these features, and are also interesting because the musical objects contained therein, SC 027 trichords repeated within each six-note motivic statement, are transformed in similar ways at multiple levels. In this article, the objects and transformations of this passage will be conceptualized in the context of a particular geometrical figure, which the reader can explore through an interactive animation with sound. To motivate and explain this choice of space, I will present a detailed analysis of measures 18–23. I will then explain how the organization of the passage’s trichords is reflected by the transformational structure of the geometric space, and how the motion between trichords mapped within the space outline hyper-transformations that help to understand structural similarities between different pitch-class groupings. Last, I will use the chosen space as a model for other related passages, demonstrating that the composer has organized elements similarly throughout the work.

A Suitable Transformational Space

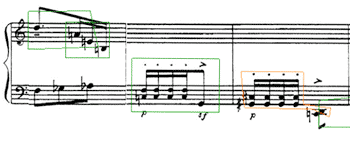

Figure 1. Pépin, Toccate no. 3, mm. 8–12

(click to enlarge)

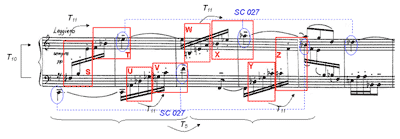

Figure 2. Pépin, Toccate no. 3, mm. 18–23

(click to enlarge)

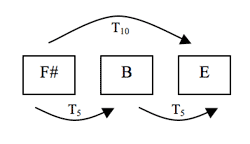

Figure 3. Transformations characteristic of SC 027 trichords (trichord <

(click to enlarge)

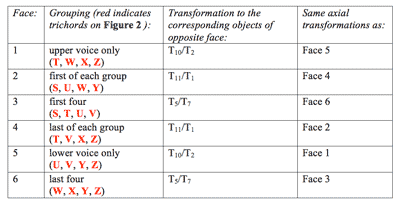

Table 1. Cubic lattice relationships

(click to enlarge)

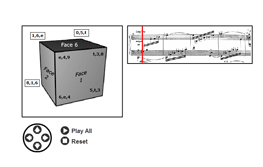

Animation 1

(click to view the animation)

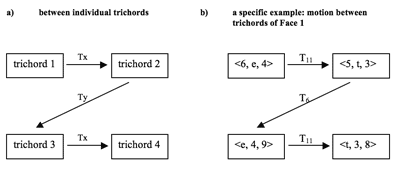

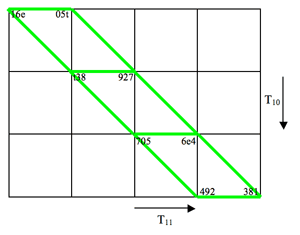

Figure 6. Motion paths and transformations between trichords, where Tx and Ty are axial transpositions

(click to enlarge)

Figure 7. Still shots from the animations on three faces of the cube

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

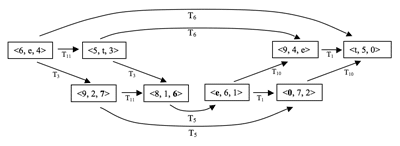

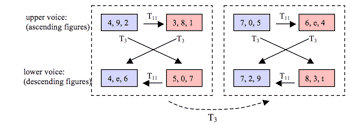

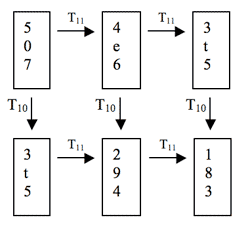

[2.1] Because trichords are emphasized throughout the Toccate via rhythm (in particular, they are isolated with rests), phrase markings, and repetition, they will form the objects of the present transformational analysis. This focus on trichords is established early on, as heard in measures 8–12 (given in Figure 1). Choosing Tn/TnI types (i.e. set classes) as the analytical objects allows one to hear an alternation between two trichord types, set classes 016 and 027, within this passage. Figure 1 shows that these two set classes are heard both in alternation and in overlap; green boxes isolate instances of SC 027 and orange boxes SC 016. These two trichords also saturate the music later on, for instance in measures 18–23, given in Figure 2. In this excerpt, instances of SC 016 are heard linearly starting on the downbeat, while instances of SC 027 are heard linearly starting on the second sixteenth of each measure. The latter grouping will be used in this analysis since it more clearly isolates the two alternating voices by emphasizing the downbeat rest, and reinforces T5 from one pitch class to the next through repetition. In addition, T5 occurs between pitch classes in both trichord types and is influential in structuring the work.

[2.2] Identifying these particular objects within measures 18–23 helps us to focus our attention on just the few transpositions that relate them, illustrated on Figure 2. T11 generates the second trichord of each measure from the first, T10 generates the upper voice from the lower, and T5 generates the second two-measure segment from the first. Some of these transformations also act on a larger scale in this passage: for example, T5 is heard from one pitch class to the next, but is also heard between two-measure segments generating a longer instance of SC 027 over measures 18–23 (indicated with dotted lines below the score on the figure). In fact, two of the characteristic transformations mentioned above, T5 and T10, are the same transformations we hear between pitch classes of the 027 trichord, shown in Figure 3.

[2.3] These are not the only transformations conceivable between the given trichords. Because the manifestations of SC 027 in

measures 18–23 all occur symmetrically in pitch-space, one might instead use inversions to demonstrate these relationships, along the lines of Figure 4a. If pitch-class relationships are expressed as standard inversions, the higher-level relationships among trichords must be expressed as hyper-transposition, as depicted in Figure 4a. If pitch-class relationships are instead illustrated with contextual inversions, as shown in Figure 4c (which expresses the idea that ordered instances of SC 027 are generated by the inversion of the first pitch class about the second to produce the third; Figure 4b is included to show the derivation of this contextual inversion), the relationships among the trichords cannot be expressed via the same contextual inversion since this transformation acts only upon individual pitch classes, not SC 027

|

Figure 4. Other possible analyses of pitch- and pitch-class relations among instances of SC 027 (click to enlarge and see the rest) |

Figure 5. A cubic lattice for Pépin’s Toccate no. 3 (click to enlarge) |

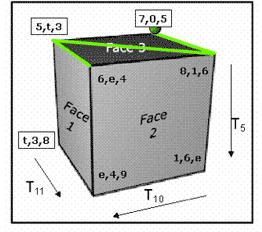

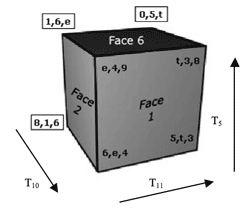

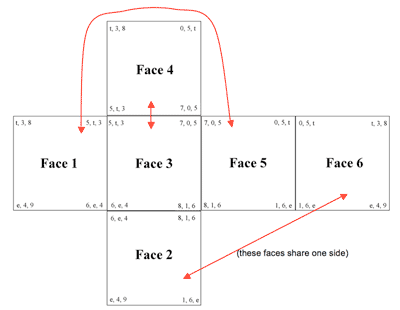

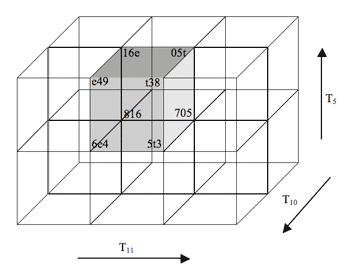

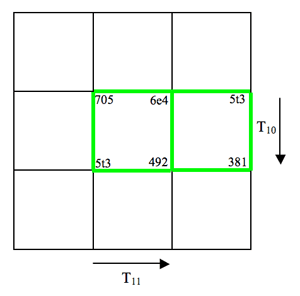

[2.4] Figure 5 presents one view of a cubic lattice incorporating the main objects and transformations of measures 18–23. The vertices of the cube represent the objects of the space, the ordered 027 trichords. These are arranged such that the cube’s three dimensions each involve one of the three main transformations of the passage, T5, T11, and T10. Thus each face of the cube represents four trichordal objects and two characteristic transformations.

[2.5] The trichord groupings isolated by each face of the cube correspond to specific groupings within the music. For example, the trichords visible on Face 1 are those of the upper voice, and correspondingly those of Face 5 (opposite Face 1) are the trichords of the lower voice. These two faces involve the same characteristic transpositions, T5 and T11 (referred to as “axial transformations” since they are depicted by the axes of the cube in the lattice) and their objects can be transformed into those of the opposite face via the remaining characteristic transposition, T10 (or its inverse, T2). Table 1 summarizes these relationships.

[2.6] Animation 1 presents this cube in an interactive application that allows the user to examine its every facet and to relate it to the music. It shows three faces of the cube. Clicking on any one of these will play the succession of trichords in the passage associated with it, and traces a zig-zag path on the cube corresponding to the order of trichords. The boxes on the score, indicating these trichords, change in accordance with the clicks. The cube can be rotated in any way by clicking on the arrows at the lower left of the frame.(3)

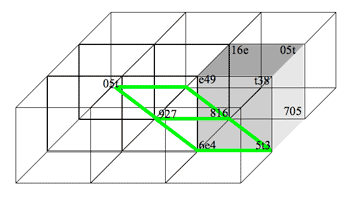

[2.7] A trichord path is given abstractly in Figure 6a: the first trichord generates the second via an axial transposition, the second generates the third by a different (non-axial) transposition, and the third generates the fourth via the original transposition. Figure 6b presents a specific example, the path between the consecutive trichords of Face 1. On this face, the trichords are transformed by <T11, T6, T11>. The similar motion-path on each face of the cube reflects the similar structures present in different levels of sequence within the passage (from trichord to trichord, from measure to measure, and from two-measure-group to two-measure-group).

[2.8] Figure 7 and its associated realizations in Animation 1 provide further instances of this shared structure. Part A of the figure shows the motion path between ordered trichords on Face 6, representing the trichord-to-trichord transformations within the passage. Part B shows the motion path on Face 2, representing the measure-to-measure transformations. Part C of the figure shows the motion path on Face 1, representing the two-measure sequence. The remaining three faces of the cube depict similar trichord groupings, and can be explored in the animation; by selecting the “play all” feature, the motion paths on the three visible adjacent faces are displayed simultaneously.

Extended Applications, 1: Hyper-relations

Figure 8. Transformational networks for the six faces of the cube

(click to enlarge)

Figure 9. Trichord-network isography under <M7>

(click to enlarge)

Figure 10. Faces whose transformations map onto one another via <M5> and <M7>

(click to enlarge)

Figure 11. Pépin, Toccate no. 3, measures 111–119

(click to enlarge)

Figure 12. Expected upper voice in Pépin, Toccate no. 3, measures 111–118

(click to enlarge)

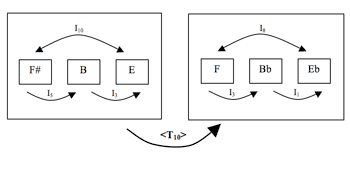

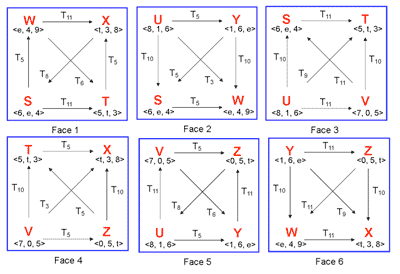

[3.1] As demonstrated in Figure 8, each face of the cube can be interpreted as a transformational network, incorporating the ordered trichords of the passage as objects, and the characteristic transpositions and their compositions as the transformations. For the sake of visual clarity I have only indicated transpositions in a single direction on the figure; however, the inverse operations may be substituted by changing the direction of the arrow. Thus the six networks can be interpreted as sharing a single node-arrow system, suggesting that the trichords progress similarly within each grouping (and thus may follow similar motion paths within the geometric space).

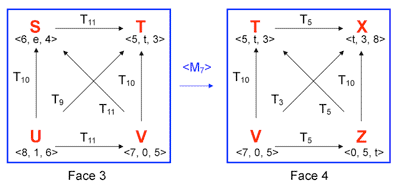

[3.2] A second transformational system at a higher structural level affects the transformations on each face of the cube. Take, for example, Figure 9. The first half of the figure shows the network of Face 3, while the second half shows the network of Face 4. The graphs of these two faces can be generated from one another by hyper-M7, an operation which multiplies the index number of each transformation by 7 and then reduces it to a mod12 equivalent. Hyper-M5, a similar operation, multiplies by 5 rather than 7. The transformational graph for each face of the cube is isographic with that of another face via hyper-M5 or hyper-M7.(4) The choice of <M5> versus <M7> depends on the viewer’s orientation toward each face of the cube: one generates the inverse transformations of the other. The graphs of each face are isographic according to Lewin’s criteria: they have the same configuration of nodes and arrows, and there is a single isomorphism that maps all transformations on one face into corresponding transformations on a second face (<M5> or <M7>).(5) Isographic pairs of faces are connected with arrows on Figure 10.

[3.3] Musically, these M-relations support several observations made in conjunction with previous figures. The principal transformations that structure the cubic lattice are T5, T10, T11 and their inverses (T7, T2, and T1); the diagonal transformations are produced by the composition of these axial transpositions. <M5> and <M7> can be applied to each of the axial transformations to produce one of the same six transpositions, resulting in an exchange of the T5/7 and T11/1 axes for one another while keeping the T10/2 axis constant. This exchange of axes at a hyper-level implies that a T5 sequence is (abstractly) analogous to a T11 sequence via <M7>, an observation already alluded to by the zig-zag motion path on each face. Thus the sequences are structured in the same manner, even though they occur at different structural levels.

Extended Applications, 2: Measures 18–23 as a model for other passages

[4.1] Although the transformational space derived from the events of measures 18–23 is interesting from a theoretical perspective, one might wonder about the value of an analysis focusing on such a short passage. In fact, the transformations introduced in measures 18–23 recur throughout the work, and thus the cubic lattice can be understood as a model for several passages. The following discussion will analyze excerpts clearly associated with the musical materials of measures 18–23 through rhythm, intervals, contour, texture, and other features.

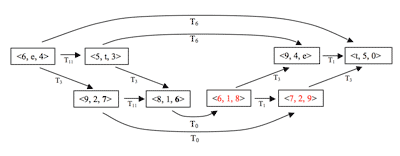

[4.2] Measures 111–119 (given in Figure 11) present music that is very similar to that of measures 18–23; both employ the same rhythm (a series of sixteenth notes starting one sixteenth after the downbeat), same dynamic level (pp), same expression (leggiero), and both feature an alternation between the right and left hands from one measure to the next. In addition to these similarities, the upper voices of measures 18 and 111 are identical, further linking the two passages. In measures 111–118, the arpeggiated trichords from measures 18–23 are heard in the upper voice, but with several distortions: while the trichords of measures 18–23 were all members of SC 027, several trichords in measures 111–118 are not. Figure 12 gives the hypothetical upper voice resulting from the pattern established in measures 18–23 (in other words, incorporating only SC 027 trichords). By comparing this with the actual score of measures 111–119, one can see that the chain of 027 trichords is only disrupted in a few locations, indicated with open note heads on Figure 12. Figure 13 presents a network that illustrates the transformations between the “expected” trichords formed from the pitch classes of Figure 12. As in measures 18–23, SC 027 trichords are transformed by T11; however, this new version reverses the melodic motion halfway through at measure 115. Thus in the second half of measures 111–118, T1 rather than T11 generates consecutive trichords. Because of this reversal, measures 115–118 can be understood as a distorted retrograde of measures 111–114. The notes indicated with open noteheads on Figure 12 are shown in bold within the network; they occur as the upper pitch class of the middle four trichords, at corresponding locations within the first and second four-measure phrases.

|

Figure 13. A network depicting transformations between trichords in the expected upper voice, measures 111–118 (click to enlarge) |

Figure 14. A second interpretation of the upper-voice pitch classes in measures 111–119 (click to enlarge and see the rest) |

[4.3] A second network, given in Figure 14a, interprets measures 111–118 in a slightly different manner. Whereas the previous network assumed a grouping structure based on that of measures 18–23, with instances of SC 027 occurring at the same metric location, the new network instead suggests that the “distorted” pitch classes establish a new grouping structure in measures 115–116 beginning on the third sixteenth-beat of the measure. Trichords affected by this change are highlighted in red on the figure. While this interpretation has a significant weakness (the third and fourth trichords are not analyzed in the same manner as the fifth and sixth, even though they have been asserted as analogous trichords within the retrograde progression), it more clearly establishes the retrograde pattern by immediately repeating pitch-class trichords {927} and {816}. It also establishes a larger-scale repeated transformation, T3. To more clearly illustrate the repeated transformations within this passage, Figure 14b and c interpret the trichords of measures 111–119 with a product network and a network-of-networks, respectively. The former emphasizes the repetition of transformations within the passage, whereas the latter emphasizes the trichordal grouping structure (that is, each iteration of the six-note motive consists of two trichords related by T11). More importantly, the combination of transformations, and the motion-path they form within a three-dimensional space whose characteristic transformations are those of the cubic lattice, will become characteristic of analogous passages later in the work, to be discussed shortly.

Figure 15. A segment of a 3D lattice based on the established cubic lattice

(click to enlarge)

Figure 16. One plane of the expanded three-dimensional lattice

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Figure 19. Motion paths along a single plane of a three-dimensional space for measures 194–198

(click to enlarge)

Figure 20. SC 027 trichords in measures 300–302

(click to enlarge)

[4.4] Since the trichords of measures 111–119 do not all appear within the original cubic lattice, a complete three-dimensional representation requires a larger structure. Figure 15 therefore gives a segment of a three-dimensional lattice based on the previously-defined cube (shaded on the figure for reference), where the vertices represent nodes containing instances of SC 027, and the three dimensions represent the transformations T5, T10, and T11.

[4.5] The motion path among trichords in measures 111–118 can also be mapped within a single tier of the expanded three-dimensional lattice given in the previous figure; this is demonstrated in Figure 16. Part (a) of the figure presents a three-dimensional view of the entire tier, and part (b) shows a two-dimensional view of the bottom horizontal plane. As in Figure 15, the shaded portion represents the original cubic lattice. The transformations T11 and T3, the main transpositions of the product network, are represented via horizontal and diagonal motion, respectively. Since T3 results from the combination of the axial transformations T11 and T10 (in fact, their inverse operations: T1T2 = T3), every trichord move within the passage can be represented along a single plane, the bottom face of the figure. The motion path repeats the same combination of transformations twice, representing the repetitive nature of the passage, and its combination of axial and non-axial transformations is reminiscent of the zig-zag pattern examined in connection with the sequences of measures 18–23.

[4.6] Several other passages reminiscent of measures 18–23 can be represented by motion paths through the three-dimensional lattice given in Figure 16, suggesting further motivic links to earlier events. Figure 17 gives measures 194–199. This music shares the rhythm and interval structure established in measures 18–23, but alternates ascending and descending sixteenth-note figures. Two types of pitch-class material overlap: SC 016 trichords in eighths, and SC 027 trichords in (mostly) sixteenth durations, the latter set class shaded on the figure (two colors are used in order to illustrate the overlap between multiple instances of SC 027). The 027 trichords involve a similar rhythm, pairing, and contour to those of measures 18–23; indeed, the transformations between trichords involve similar transformational relationships to those of measures 111–119. The trichords of measures 194–199 are depicted transformationally in Figure 18. Observe that SC 027 pairs within the same ascending or descending figure involve a transformation of T11, and that these pairs of trichords generate the next via T3 (also the transformation from one two-measure section to the next). Because measures 111–119 involve the same combination of transformations, the trichords of measures 194–199 can be mapped with the same combination of motion paths as seen in Figure 15. This new mapping is shown on Figure 19; unlike Figure 16, the new motion path begins on trichords <4, 9, 2> and <3, 8, 1> (rather than <6, e, 4> and <5, t, 3>) and presents four diagonal moves instead of three.

|

Figure 17. Pépin, Toccate no. 3, measures 194–199 (click to enlarge) |

Figure 18. A network depicting transformations between unordered 027 trichords in measures 194–198 (click to enlarge) |

[4.7] The final passage reminiscent of measures 18–23 occurs near the end of the work, in measures 300–302 (Figure 20). SC 027 trichords are heard in the two voices of this passage; the upper voice begins its 027 trichords on the third sixteenth note, G, of measure 300,(6) while the lower voice begins its trichords on its first sixteenth note, F. Figure 21 gives a network illustrating the transpositions between these trichords. A move of T11 is heard from one trichord to the next, and the music of the upper voice is transformed by T10 to generate that of the lower voice. The two prominent transpositions in this passage are the two axial transformations characteristic of Figure 16 and Figure 19, and for this reason the motion path between trichords in measures 300–301 can be mapped in the same plane of the three-dimensional space. Figure 22 gives this mapping. Unlike the two previously-examined passages, this music involves T10 transformations, generating vertical rather than diagonal paths.

|

Figure 21. A product network demonstrating transformations between SC 027 trichords in measures 300–301 (click to enlarge) |

Figure 22. Trichord mapping within a single plane depicting motion within measures 300–301 (click to enlarge) |

Conclusion

[5.1] The preceding examples have demonstrated how the cubic lattice and its associated two-dimensional spaces can provide a framework for interpreting transformational relationships in various passages. Indeed, its broad applicability results from Pépin’s replication of the characteristic transformations and objects of measures 18–23 throughout the work. While the three passages analyzed above, measures 111–119, 194–198, and 300–302, clearly use motives and rhythms similar to those of measures 18–23, their related transformational structures are not immediately apparent. The space of Animation 1 helps us to perceive commonalities among these objects and transformations via repeated visual motifs such as the shared zig-zag motion path. Furthermore, the repetition within the motion paths of measures 111–119, 194–198, and 300–302 is reminiscent of the sequences outlined in measures 18–23, providing another link to the original passage (these passages do not involve multiple overlapping sequences as heard in measures 18–23, but instead develop the motive at a single level).

[5.2] The hyper-transformations discussed in conjunction with measures 18–23 transformed the graphs of different cube faces into one another. These relationships support the idea that the various sequences of the passage, occurring at different structural and transpositional levels, are analogous. Conceptually, <M5> and <M7> swap T5 and T11 axes/operations for one another; these two transformations correspond to the longer-scale and local processes, respectively, in Pépin’s original sequence.

[5.2] Other spaces are possible for the characteristic transformations presented here. The analysis of Berg’s op. 2, no. 2 presented in this issue of Music Theory Online presents a toroidal space incorporating the same transformations. That choice of space emphasizes the congruence of melodic, metric, and textual elements within the Berg Lied, whereas the cube space presented in this paper emphasizes the similar structure of sequences involving different transposition levels. The animation can be explored further to hear different sub-groups, sequences, and combinations of groupings. While this type of analysis may not be practical for every example, it does provide interesting insights into structural similarities, recurring motivic relationships, and the congruence of a group of two-dimensional spaces.

Stephanie Lind

Queen’s University School of Music

Harrison-LeCaine Hall

39 Bader Lane

Kingston, ON

K7L 3N6 Canada

linds@queensu.ca

Works Cited

Brown, Stephen C. 2003. “Dual Interval Space in Twentieth-Century Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 25/1: 35–57.

Gollin, Edward. 1998. “Some Aspects of Three-Dimensional ‘Tonnetze’.” Journal of Music Theory 42/2: 195–206.

Klumpenhouwer, Henry. 1998a. “The Inner and Outer Automorphisms of Pitch-Class Inversion and Transposition: Some Implications for Analysis with Klumpenhouwer Networks.” Intégral 12: 81–93.

—————. 1998b. “Network Analysis and Webern’s Opus 27/III.” Tijdschrift voor Muziektheorie 3/1: 24–37.

Kochavi, Jonathan. 1998. “Some Structural Features of Contextually-Defined Inversion Operators.” Journal of Music Theory 42/2: 307–320.

Lambert, Philip. 2000. “On Contextual Transformations.” Perspectives of New Music 38/1: 45–76.

Lewin, David. 1982–83. “Transformational Techniques in Atonal and Other Music Theories.” Perspectives of New Music XXI/1–2: 312–71.

—————. 1987. Generalized Musical Intervals and Transformations. New Haven: Yale University.

—————. 1990. “Klumpenhouwer Networks and Some Isographies That Involve Them.” Music Theory Spectrum 12: 83–120.

—————. 1993. Musical Form and Transformation. New Haven: Yale University Press.

—————. 2008. “Transformational Considerations in Schoenberg’s Opus 23, Number 3.” In Music Theory and Mathematics: Chords, Collections, and Transformations, ed. Jack Douthett, Martha M. Hyde, and Charles J. Smith, 197–221. Rochester: University of Rochester Press.

Morris, Robert. 1987. Composition with Pitch Classes: A Theory of Compositional Design. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Peck, Robert. 2004–05. “Aspects of Recursion in M-Inclusive Networks.” Intégral 18–19: 25–70.

Footnotes

1. These contextual inversions are modeled on those of

Lewin, as discussed in Lewin 2008. Earlier references to contextual inversions can be found in Lewin 1993, Kochavi 1998, and Lambert 2000.

Return to text

2. Technically, the arrows and transformations among different object types are not “the same” since one type of arrow may represent a change of pitch class, and the other type represent may represent a change from one trichord to another, one network to another, and so forth. However, they function analogously.

Return to text

3. This interactive animation was designed by Stephanie Lind and animated by Reuben Heredia.

Return to text

4. Isography via hyper-M5 and -M7 is

discussed in Lewin 1990, 88; note that the automorphisms of hyper-M5 and -M7 are notated in the form F<5, j> and F<7, j>, respectively, in Lewin’s article.

Return to text

5. Ibid.

Return to text

6. The previous two pitch classes can be understood as part of an incomplete 027 trichord.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2009 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by William Guerin, Cara Stroud, and Tahirih Motazedian, Editorial Assistants

Number of visits: