Subjectivity and Structure in Milton Babbitt’s Philomel

Emily J. Adamowicz

KEYWORDS: Babbitt, Philomel, Hollander, twelve-tone, psychology, aesthetics, hermeneutics, text-music

ABSTRACT: The music of Milton Babbitt is often considered to be positivistic due to the color of his theoretical writings. Yet Babbitt's writings about music do not substitute for his actual musical works and, although the composer was mistrustful of aesthetic interpretation, his music has frequently been shown to support such criticism. Building upon past efforts by Mead and Lewin, I explore the hermeneutic and aesthetic value of what is arguably his most expressive work, the 1964 soprano and tape piece, Philomel.

Copyright © 2011 Society for Music Theory

[1] There is no doubt that Milton Babbitt’s writings are distinctly positivistic in their tone. Babbitt has argued both explicitly and through example that music theory should model itself after scientific theory. He has been an advocate for clarity in communicating music-theoretic concepts and has openly attacked what he refers to as “easy evaluatives” and “incorrigible personal statements” that cloud and mar “responsible normative discourse” (Babbitt 1965, 50). The absence of interpretative claims in Babbitt’s writings might suggest that the composer has removed hermeneutics from his musical world entirely. Yet in a work like Philomel it is difficult, given the inherently dramatic nature of the text, to avoid interpreting the music regardless of whether or not one may be entering the “never-never land of putative denotative reference,” to use Babbitt’s words. The 1964 work for soprano and tape captures the psychological dissolution of a woman in the aftermath of a brutal rape, mutilation, and confinement. As McClary (1989, 75) has observed, very few students who are new to this work can listen and remain unmoved. Needless to say, the work has engendered many responses that grapple with the emotionally arresting aspects few can resist. Given the aesthetic and emotive power of the work, it seems unlikely that the music is disengaged from the powerful thematic implications of Hollander’s text. Based on this assumption, I explore the possibility that the themes in Hollander’s poetry are embedded in the music in efforts to bring the positivistic aura surrounding Babbitt’s words into dialogue with the emotive power of what is arguably his most widely communicative music. The never-never land of interpretation simply beckons too strongly to resist.

Example 1a. Babbitt. Philomel, measures 1-7.

(click to enlarge)

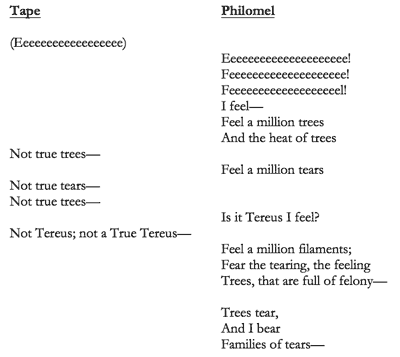

Example 1b. John Hollander’s Philomel, excerpt.

(click to enlarge)

Example 1c. Twelve-tone matrix for Philomel.

(click to enlarge)

[2] In the sordid world of Ovid’s mythology takes place the rape of Philomel at the hands of her sister Procne’s husband, Thereus, who cuts out Philomel’s tongue in order to silence her after the attack. In her confinement, Philomel weaves a tapestry depicting her assault and sends it to her sister. During a Bacchanalian festival, Procne rescues Philomel and the two murder Thereus’s son and feed him the boy’s body. In the revenge’s aftermath, the sisters flee into the woods pursued by Thereus and the three are transformed into birds. Babbitt’s Philomel takes place at the moment before Philomel’s transfiguration into a nightingale and ends when Philomel transubstantiates into a new form. Previous studies of the work, both analytic and aesthetic, have focused on the opening, shown in Example 1a. Hollander’s initial text for Philomel appears in Example 1b.

[3] Mead (2004) has commented on the grasping nature of the voice in this passage. Philomel’s voice emerges not distinctly, but almost “humming” with a long sustained high E, and then begins to reach for other notes, what Mead refers to as a “fishing expedition.” He observes: “my overall sense of this passage is of a voice first feeling its way into a musical space, then carving out for itself a place to make music” (Mead 2004, 263). Her voice begins to search for itself and becomes more fully realized as the music progresses. Here, the mute Philomel, silenced by mutilation at the hands of her rapist, takes the first tentative steps toward self-expression through music. It is clear that the repetition of the high E corresponds to the opening phoneme of John Hollander’s text, which, tentatively, one phoneme at a time, comes to express an intelligible word. Hollander describes the opening as the following:

The first [section], a prolonged equivalent . . . of recitative and bits of arioso, starts out . . . with a sustained presentation of the vowel nucleus /iy/, the core of the phrase “I feel,” for it is from her fear, fancied outrage, and remembered pain that Philomela’s psychic energy in the song is generated. The opening section develops by permutations of the phonemes of the words of Philomel and Tereus, the sequences feel a million, filaments and tears, trees, tears (verb), etc. eventually expanding into more coherent phrase groups and finally stanzaic clauses (Hollander 1967, 136).

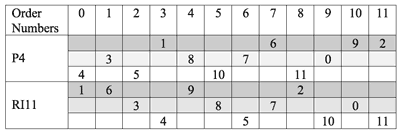

[4] As Lewin (2006) and Swift (1976) have noted, the music also expresses an incremental expansion from a single pitch from one row form to include more and more pitches of subsequent row forms.(1) The twelve-tone matrix for the work is shown in Example 1c. The voice, beginning with the initial pitch class of P4, then expands to encompass two pitch classes of P5, then three of P3, then four of P7, etc. When the voice reaches pitch class 4 in the diagonal in the matrix, the subsequent row is begun with the remainder of each expressed in the underlying vertical harmonies. Following this pattern through to P10, with pitch class 10 as the final note in the opening vocal line, yields the aggregate. In this passage, the structure of the music is analogous to the structure of the poetry. Babbitt has acknowledged that, in the opening, “the set structure was shaped by my primary wish to project, at the outset of the piece, both explicitly interpreted set forms and the programmatically suggested reiteration of a single pitch” (Babbitt 1976, 6). The recurrent high E correlated to the diagonal is what leads Mead to describe a tentative voice emerging into musical space, taking only one step at a time, and fearfully returning to single point again and again.

[5] But the potential for interpretation in the opening goes deeper still. In his discussion of this passage, Lewin (2006) compares Babbitt’s navigation of the matrix to Philomel’s weaving of her story into a tapestry for her sister. While Ovid’s Philomel reveals her story through the threads of the tapestry, the musical Philomel unveils herself through the threads of the serial matrix. Lewin proposes that “Babbitt’s Philomel [is] speaking through the web of the serial matrix through those painstakingly interwoven threads. Nothing lies closer to her than the laborious work of composing her piece through Babbitt as a medium” (Lewin 2006, 394). To sing Philomel is to weave Philomel’s tapestry. Lewin further connects Procne’s maternal instinct to protect her sister with the Latin word “matrix” meaning “mother.” He attributes maternal qualities to the matrix insofar as it is a generator of serial music. This maternal element is also seen in Philomel, who gives birth to the horrible artwork through her union with Thereus. I would propose yet another connection between Philomel and Procne that emerges from their mutual acts of revenge and connects directly to Babbitt’s serial procedures. Though not addressed in Hollander’s poetry, in the Ovidian myth Philomel seeks vengeance by exposing the crimes of her rapist through the careful weaving of a tapestry while Procne exacts revenge by murdering her son and cooking him into a feast for her husband. Both weaving and cooking are quiet, deliberate, and calculated activities. One does not weave a tapestry nor bake a pie in the heat of passion, but in cool calculation. The adage “revenge is a dish best served cold” could be invoked to describe both Philomel’s weaving of a tapestry and Procne’s cooking of her own son. Both women are using traditional domestic activities to exact their revenge. The fruits of domestic labor are transformed into weapons of justice and punishment. Philomel’s meticulously woven tapestry can be likened to Babbitt’s serial matrix in terms of its requisite calculation and careful construction. This somewhat dispassionate calculation opposes the passionate rage felt by the victim of assault and speaks to the fragmented nature of Philomel’s psyche—a splitting of her personality. The coexistence of these different modes of thought also manifests itself at the musical surface in terms of how the individual row forms are expressed. Babbitt does not confine row forms to individual voices; rather the row is shared between the live singer and the taped voice. At a surface level, the distribution of structures can function as a metaphor for the fragmentation of Philomel into two Philomels, the live and the taped. The live voice is no more or less Philomel than the taped voice—they are both given the means to speak through the serial matrix.

[6] The disintegration of Philomel becomes all the more apparent in the “Echo Song.” Hollander describes the Echo Song as the following:

[The Echo Song] . . . is supposed to take place after her transformation [to a nightingale] and consists of a dialogue with the various birds of the air, in which she implores them to support her in her new identity as a bird. The echo-song was a favorite device of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century satiric verse; the point was to use the echoing last word of a question for a debunking answer...I felt that the resources of the synthesizer would allow me to build an echo song by cutting word boundaries and even setting up new consonantal clusters in a manner that had not been done before, the effect to be horrific in a kind of baroque way, but not coyly humorous (Hollander 1967, 136).

While Hollander proposes that the dialogue is external, meaning that Philomel is engaged with an object outside of herself—in this case other birds of the air—the aesthetic effect conveyed in Babbitt’s music is of self-dialogue. Both the live and the taped voices are Bethany Beardslee’s, which again reinforces the notion that Philomel’s personality has been split. The idea of a musical echo is realized by Babbitt in parts I–III and then in part V of the Echo Song with the simple repetition of row forms. Part IV does not use this technique. The five verses of the Echo Song are shown in a text-row diagram, Example 2, which matches the appearance of the row’s start points to their accompanying text. (For a better sense of how this diagram represents the musical surface, the complete part I, shown in Example 3b, is discussed below.) While the repetition of row forms may seem like a relatively simple technique, Babbitt uses a more intricate device that connects the echo to Philomel's psychic fragmentation in a more sophisticated fashion.

|

Example 2. Text-row correlation for parts I-V of the Echo Song, Philomel. (click to enlarge) |

Example 3a. Mutual partitionings of P4 and RI11. (click to enlarge) |

Example 3b. Pitch reduction of Philomel, Echo Song I, measures 132-144.

(click to enlarge)

Example 3c. Mutual partitions of P4 and RI11.

(click to enlarge)

Example 4a. Mutual partitioning of I5 and R10.

(click to enlarge)

Example 4b. Pitch reduction of Philomel, measures 249-260.

(click to enlarge)

[7] The clue to his technique lies in a brief mention of the Echo Song in which he offers a short description of the “mutual partition” (Babbitt 1976, 6).(2) Through these partitions the distinction between row forms becomes blurred. If two rows can be expressed by the same partition, they lose their unique identity and instead participate in a network of related row forms. The concept of the mutual partition is outlined in Example 3a, which shows two rows, P4 and RI11, being partitioned into three ordered pitch-class sets: [1 6 9 2], [3 8 7 0], and [4 5 10 11]. In the first Echo Song, Babbitt exploits these three pitch-class sets at the surface of the music to blur the distinction between these two rows, shown in Example 3b. The first system of the example has lines that connect the contiguous pitches of the row. While at the surface the music appears to convey a straightforward presentation of RI11 and P4, the repetition of these three partitions reveals the mutual partitions. Example 3c shows these partitions arranged according to the order in which each pitch class appears within the two rows. Certain symmetrical properties emerge. In the first partition for P4, (1 6 9 2), interval classes between the order numbers (3 7 10 11), ic set [4 3 1], are preserved in the same partition in RI11 but in retrograde. In the second partition of P4, (3 8 7 0), interval classes between order numbers (1 4 6 9), ic set [3 2 3], are preserved in the same partitioning in RI11. In the third partition of P4, (4 5 10 11), interval classes between order numbers (0 2 5 8), ic set [2 3 3], are preserved in the same partitioning for RI11 but in retrograde. These partitions share the identities of two distinct row forms and, if given only the partition, it is impossible to tell which row Babbitt is employing. In this sense, mutual partitions are reminiscent of Hollander’s use of common phonemes in the piece’s opening where they anchor networks of related words but are, in themselves, unstable until they assume the identity of a context. A prime example is the relationship between tears (as in crying) and tears, the verb.

[8] Another example of mutual partitioning appears in a section of the work that also employs the echo. Shown in Example 4a are three partitions of I5 and R10: [5 4 11 10], [8 3 0 7], and [6 1 2 9] respectively. Again, these partitions are clearly expressed at the musical surface, shown in Example 4b. Referring to Example 4a, the first partition retains the interval classes between order numbers in retrograde, as does the second partition. The third partition retains identical interval classes between order numbers. In addition to capturing Philomel's fragmented psyche at a purely aesthetic level, Babbitt’s musical structures are inhabited by the same instability. This text-music relationship, like the one seen in the work’s opening, indicates an acute awareness on the part of the composer of Hollander’s thematic concerns.

[9] Babbitt’s treatment of the echo aligns the music of Philomel with the greater concerns of the poet. Hollander speaks in great detail about the echo in The Figure of Echo:

The echo device, then, may be embodied in epigram or song or dramatic scene. Potentially, it can augment and trope the utterance it echoes, as well as reduce and ridicule. It can even serve a semantically redundant and more purely “musical” function, one which we associate with certain types of refrain (Hollander 1981, 31).

Hollander clarifies the type of echo used in Philomel as the “epistrophe,” or the literal repetition of a word or phrase in “successive cadential positions.” Though not speaking about Philomel, Hollander does address the device of the echo song such as the one he uses in Philomel. He sees the effect of this echo as a “whole phrase being transmitted, partly in clear focus and partly blurred” (Hollander 1981, 94). Babbitt makes use of the effect of the live voice and taped voice to convey Philomel both in and out of focus. The presence of the live singer is immediate while the taped voice is disembodied. This disembodied voice is Philomel and yet it is not Philomel. Her psyche bears further signs of disintegration, as it is ultimately she who answers her own questions. Hollander discusses the disembodied voice and, once again, though not speaking of Philomel directly, his sentiment resonates strongly with this piece: “the crucial request for location of the disembodied voice that, wherever it is, occupies no space. Echo is voice’s self” (Hollander 1981, 61). Mead expresses a similar sentiment: “a prominent thread in my experience of Philomel involves a sense of the voice, of song, of self, found in the face of overwhelming trauma, change, and confusion” (Mead 2004, 262). When Philomel echoes herself, the nature of her self and identity are called into question. Her identity becomes unstable as she moves closer to the moment of transfiguration. As the poetry progresses, Philomel becomes further and further disengaged from her original identity through the disembodying power of the echo.

[10] It could also be argued, however, that Philomel, destined by myth to become a nightingale for eternity, comes closer to expressing her true self through the echo. The disembodying power of the echo facilitates her literal disembodiment into an ultimate and essential nature. The idea that, through the echo, Philomel comes closer to a truer self-identity can be further explored through Hollander’s writings. Hollander proposes that pure literal reiteration can lessen and decay the meaning of an echo and that the echo must have a life of its own and either contribute or reveal latent content. In Ovid’s mythology, the nymph Echo loses the power to converse and can only reiterate that which is said to her by another. In a similar fashion, left mute with weaving as her only means of communication, Philomel can articulate nothing but the tragedy of her assault, a burden given to her by another. But through Babbitt’s music, a truer portrait of her psychic condition is revealed. In line with Hollander’s description, the echo in Babbitt’s music reveals latent content in the myth. As Hollander says, “Echo’s power is thus one of being able to reveal the implicit” (Hollander 1981, 27). Philomel’s anguished voice is implicit in Ovid’s text yet it is not given sound and substance until Hollander and Babbitt provide one.

[11] In a different vein, the echo is also significant to the relationship between Babbitt’s work and Ovid’s myth. Hollander observes the capacity of the echo to invoke aspects of preexisting works and posits it as a form of citation. Hollander proposes the term metalepsis, meaning transumption, for echoes that seem to exist in a conceptual space with their “original” rather than a linear space. Babbitt and Hollander’s work embodies this type of echo insofar as it functions in an intertextual space with Ovid’s myth. By distorting the original voice in order to interpret it, Babbitt’s music participates in a dialogue surrounding the myth and contributes a new dimension of meaning to it.

Example 5. Pitch reduction of Philomel, measures 308-320.

(click to enlarge)

Example 6. Pitch reduction of Philomel, measures 321-336.

(click to enlarge)

[12] The idea of transumption parallels Philomel’s theme of transfiguration as well. In Ovid’s myth, Philomel is forever changed by her trauma and becomes transfigured into a nightingale. But more than just physical transformation, she transubstantiates into the music of the nightingale, which forever echoes her tragedy. The dissolution of her physical being further manifests itself in the musical structures of Babbitt’s Philomel. As the work progresses, complete rows give way to smaller units, recurrent dyads, shown in Example 5, which partition the musical surface in a way not seen before in this piece. In this example, slurs indicate a repeated dyad in the same voice while the lines indicate contrapuntal repetitions of dyads similar to the voice-exchange. The first pair of dyads, [7 4] and [6 9], evince the final tetrachord of I2. The second pair, [10 8] and [11 1], evince the final tetrachord of P3 while the third pair, [2 3] and [0 5], evince the final tetrachord of P7. If taken as RI2, P3, and R7 instead, it becomes possible to mutually partition each P-form with the I-form in the manner seen in the Echo Song, lending RI2 a certain centricity in this passage. These partitions do not, however, appear at the musical surface. Additionally, the first tetrachords of P1, P6, and R3 are suggested in measures 316–318, set against the recurrent dyads, with further splintering of serial material as Babbitt takes the first and final dyads from RI9 and P8 in measures 319–320. One gets the impression that Babbitt is urgently moving through serial pitch-class space and, as Mead has suggested, evoking Philomel’s frantic “thrashing through the woods of Thrace.”(3) Philomel’s momentum is building but, as she repeats the same steps over and over, her motion becomes arrested. That this change in surface texture corresponds to the text “I ache in change” suggests the mounting pressure that ultimately causes her dissolution. Near the end of the work, in a passage shown in Example 6, there are clear presentations of row forms set amidst the dissolving twelve-tone landscape. On the line of poetry, “I die in change,” musical space is liquidated to coincide with the theme of transfiguration. Through the dissolution of musical space, Philomel is permitted to die and become reborn into the ether. The final appearance of I0 signals one of the last vestiges of Philomel as a worldly being. It is a final stand of logic, of reason, and, above all, of coherence. Nearing the moment of the work’s termination, the fantastical unreality of Ovid’s myth takes over. Philomel transubstantiates, and the work enters the realm of the metaphysical, rather than the actual.

[13] But what does this mean for interpreting Babbitt’s music? In Philomel, at least, structure is ruled by poetry, which endows the musical surface with the emotion and power of the mythological themes. Music becomes myth, myth becomes music, and the dissolving psyche of a tragic heroine is given expression. It becomes possible that the figurehead of positivistic discourse in North American music theory possessed the capacity to empathize with the psychological condition of a wronged and increasingly unstable woman. But more than this, Babbitt demonstrates a grasp of the meta-musical through his sensitive treatment of Hollander’s poetry. While hermeneutic and aesthetic theorizing does not inhabit Babbitt’s writing, they become indispensable to capturing the true significance of this work. Ultimately, there is great reward in drawing Babbitt’s music into the never-never land of interpretation.

Emily J. Adamowicz

University of Western Ontario

London, Ontario

eadamowi@uwo.ca

Works Cited

Babbitt, Milton. 1965. “The Structure and Function of Music Theory.” College Music Symposium 5: 49–60. Reprinted in Boretz and Cone, eds. 1972. Perspectives on Contemporary Music. New York: Norton.

—————. 1976. “Responses: A First Approximation.” Perspectives of New Music 14, no. 1: 3–23.

Haimo, Ethan. 1984. “Isomorphic Partitioning and Schoenberg's Fourth String Quartet.” Journal of Music Theory 28, no. 1: 47–72.

Hollander, John. 1967. “Notes on the Text of Philomel.” Perspectives of New Music 6, no. 1: 134–141.

—————. 1981. The Figure of the Echo: A Mode of Allusion in Milton and After. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Lewin, David. 2006. Studies in Music with Text. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

McClary, Susan. 1989. “Terminal Prestige: The Case of the Avant-Garde Music Composition.” Cultural Critique 12: 57–81.

Mead, Andrew. 2004. “‘One Man’s Signal is Another Man’s Noise’: Personal Encounters with Post-Tonal Music.” In The Pleasure of Modernist Music: Listening, Meaning, Intention, Ideology, ed. Arved Ashby. Rochester, New York: University of Rochester Press.

Swift, Richard. 1976. “Some Aspects of Aggregate Composition.” Perspectives of New Music 14, no. 2: 236–248.

Footnotes

1. Swift describes the opening as a twelve-voice canon and observes that “the twelve voices of the canon individually state the inversion transpositions that appear along the first line of the matrix. In the first vertical aggregate, each pitch-class number, therefore, has two immediate referential meanings: it is at once a member of P and the initial element of one inversion form. Reading from left to right along the top line of the matrix will give the initial pitch-class number of each of the twelve voices in the first vertical aggregate in descending order from top to bottom” (Swift 1976, 241). The notion of a pitch class or group of pitch classes possessing two identities is relevant to my argument that Babbitt is musically representing Philomel’s fractured psyche through Janus-faced structures. Further analyses and commentary appear later in this article.

Return to text

2. These partitions are similar to Ethan Haimo’s “isomorphic partitions,” which involve “the creation of an identical partition of the transformation of a row so as to produce significant invariant relationships” (Haimo 1984, 48). While the partitions discussed in this article are tetrachordal, partitions can be of varying size and number.

Return to text

3. In a personal communication between Andrew Mead and the author.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2011 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Michael McClimon, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

6,878