Copland’s Fifths and Their Structural Role in the Sonata for Violin and Piano

Stanley V. Kleppinger

KEYWORDS: Aaron Copland, pitch centricity, tonal structure, violin sonata

ABSTRACT: Perfect fifths occupy a privileged role in much of Aaron Copland’s music. This essay explores the structural significance of ic-5 emphases in the Sonata for Violin and Piano suggested by the pairings of particular pitch centers. In the perspective offered here, pitch centers and other pitch events at the music’s surface parallel the entire work’s tonal organization via a network of perfect-fifth relationships.

Copyright © 2011 Society for Music Theory

“I remember in an early lesson my bristling when he said, ‘How come you always use intervals like minor thirds and major sevenths? Why don’t you ever use a perfect fifth?’”

—Jacob Druckman on Aaron Copland (Copland and Perlis 1989, 129)

[1.1] Example 1 illustrates a facet of Copland’s music that is familiar to most students of it: emphasis on the perfect fifth (and its inversion to a perfect fourth) is a characteristic element of his mature musical language. Example 1a shows the opening of Billy the Kid, harmonized in parallel perfect fifths. Example 1b presents the famous polychord that introduces Appalachian Spring, which superimposes two major triads with roots separated by a perfect fifth. Example 1c is the first melody of the Third Symphony, saturated with melodic fourths and fifths. Even an excerpt from his serial Piano Fantasy is controlled by harmonies replete in interval class 5, as shown in 1d.

[1.2] One of our most ubiquitous music history textbooks summarizes Copland’s “Americanist idiom” by citing his “transparent, widely spaced sonorities, empty octaves and fifths, and diatonic dissonances” (Burkholder et al. 2006, 888, emphasis added). As the excerpts of Example 1 demonstrate, this text—in reflection of many other summaries of Copland’s style—likely intends Copland’s “fifths” as a token for emphasis of the perfect fifth as well as its inversion, the perfect fourth. This essay begins with a brief exploration of the roles played by interval class 5 in selected works by Copland in the 1930s and 40s. This survey will show that, in addition to serving as a stylistic marker, ic 5 can have implications for large-scale tonal organization in Copland’s music. His Sonata for Violin and Piano epitomizes the ways in which ic 5 can provide cohesion between musical surface and large-scale structure, and thus becomes the main analytic focus of this paper.

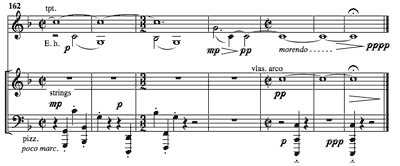

Example 2. Piano Sonata, conclusion

(click to enlarge)

Example 3. “Nature, the gentlest mother,” measures 1—8

(click to enlarge)

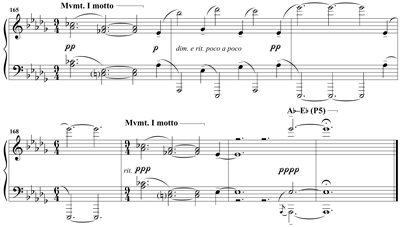

Example 4. Quiet City, conclusion (measures 162—168)

(click to enlarge)

[1.3] In addition to simply characterizing the harmonic and melodic language of a cross-section of Copland’s output (as illustrated in Example 1), the fifth can serve in his music as a stabilizing element. The quintessential example of this practice comes from the conclusion of his Piano Sonata, reproduced in Example 2. The two-chord motto of measures 165 and 169 is a transposition of the first movement’s clangorous opening, now hushed and irresolute. This motto is answered by widely-spaced, diatonic counterpoint that comes to rest first on bleak

[1.4] In contradistinction to the fifth’s role as a stabilizing agent in the Piano Sonata, tonal ambiguity between ic-5 related pitch classes characterizes other contemporaneous Copland pieces. The first of his Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson, “Nature, the gentlest mother,” opens as shown in

Example 3 with much emphasis on

[1.5] Similar tonal ambiguities between ic-5 pitch classes color perception of the conclusion of Quiet City, shown in Example 4. Critics have described this music as wavering between focus on C and on F;(3) the conclusion on C is either perceived as a “dominant” of F or as a mixolydian tonic approached by its fifth. As Howard Pollack puts it in his biography of the composer, “Whether one considers the final pitch an unresolved dominant or a more restful tonic, the work ends on a hesitant note; ...the music raises more questions than it answers” (Pollack 1999, 332).

[1.6] Another example of this practice is embodied in the opening from the Third Symphony’s scherzo movement, shown in Example 5. The horns’ first perfect fourth might suggest its upper note, F, as tonic in a lydian context (reinforced by the timpani’s downbeat), though the motive’s ultimate C might instead be apprehended as a pitch center, approached with a pronounced plagal flavor. This perfect-fifth duality gives rise to a more complex context as the music continues. When the six-sharp diatonic collection is abruptly asserted at measure 7, the main motive is transposed so that the F/C duality is replaced by B/

|

Example 5. Third Symphony, II, opening (click to enlarge) |

Example 6. Violin Sonata, I, measure 1—20 (click to enlarge) |

[1.7] One of Copland’s most exquisite tonal ambiguities between ic-5 related pitch classes begins his Sonata for Violin and Piano, displayed in Example 6. The pianist’s right hand presents oscillating A-major and D-major triads in measures 1–6. The right hand’s A and D triads seem to point to D centricity, as their reference to the traditional dominant-tonic relationship is projected in its own discrete register. Meanwhile, the repeated returns to long Gs in the lowest register at phrase endings (measures 3 and 6) lend salience to this pitch class. The violin’s first three entrances comment on this ambiguity between D and G by stressing the roots and thirds of both these major triads and by starting and ending each phrase on the single common tone they share. As this passage unfolds,

[1.8] Whereas the perfect fifth is emblematic of so much of Copland’s music—and specifically his best-known music from the late 1930s through about 1950—the last few examples point to a body of works that specifically spin out dual foci on pitch classes related by this interval. An opening like those of the Third Symphony’s scherzo or the Violin Sonata almost inevitably begets speculation about the consequences of that duality for the rest of the work. Especially in the case of the Violin Sonata, the potential relationships between the G/D duality framing the first movement and pitch centers established elsewhere in the piece cry out for investigation. This essay examines the sonata in light of this observation, showing how the pitch classes of this concomitant emphasis of G and D and their ic-5 relationship have consequences for the tonal structure of the entire work.(4) In this perspective, the perfect fifth becomes much more than a characteristic element of Copland’s melodies and harmonies. By tracing connections among pitch centers, formal units, and salient events on the music’s surface, it becomes possible to observe the perfect fifth steering the tonal organization of each of the sonata’s three movements as well as providing coherence to the entire composition.

Example 8. Violin Sonata, I, measures 21—39

(click to enlarge)

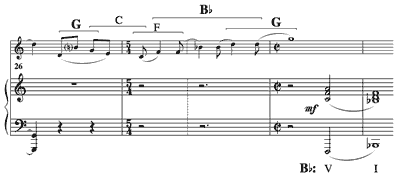

Example 9. Analysis of Violin Sonata, I, measures 26—29

(click to enlarge)

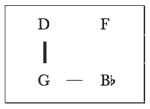

Example 10. Network of fifths and thirds

(click to enlarge)

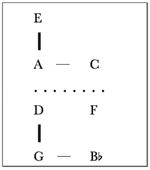

[1.9] The perfect fifth defining the opening G/D duality immediately spawns another tonal issue that must be considered before surveying the rest of the work. The initial movement’s prologue is followed by a new theme as shown in Example 8. This theme begins in measure 21 by arpeggiating a G-major triad, but ascends through a pair of perfect fourths to land at

[1.10] This partnering of pitch classes related by minor third is reflected in the remaining authentic cadences of Example 8. After the violin completes a repetition of the melodic pairing of G and

[1.11] In congruence with the approach seen thus far, the sonata’s subsequent pitch centers frequently emerge in pairs related by perfect fifth or third. The music’s presentation of these pitch centers itself suggests such pairings, much as the prologue suggested the linking of G to D and G to

[1.12] As the first movement develops, it moves further and further from the G/D focus by emphasizing pitch classes progressively more remote (as considered in terms of fifths and thirds) from this focal point before closing with a restatement of the prologue music that returns to the G/D ambiguity. The second movement, shorter and tonally less complex, is based upon a D/A tonal focus (which relates to the G/D focus of the first movement in obvious ways). After the first two movements explore the intervallic connections suggested by this tonal network, the third expands its principles, substituting major-third relationships for the minor thirds emphasized in the first two movements. The use of major-third related pitch centers in place of minor-third relations is itself suggested later in the first movement, as the subsequent analysis will show. The last movement’s coda reminisces on the first movement’s prologue once more while recalling the tonal excursions of the entire sonata.

[2] The First Movement

[2.1] Example 11 lays out the pitch centers and the thematic elements of the Violin Sonata’s first movement. Pairs of pitches separated by a slash represent situations analogous to the already-explored prologue, wherein two pitch classes a perfect fifth apart are stressed concomitantly. Pairs of pitches separated by a dash signify minor-third related pitch classes that receive emphasis via the “Tempo II theme” first appearing at measure 21, as seen in Example 8 above. The abbreviation “A. C.” refers to authentic cadences that help to define various pitch centers throughout the movement.

[2.2] The movement can be considered in three large parts: the exposition of tonal issues, a development that is interrupted by a “Lyrical Middle Section,” and a final area restating the rhetoric and themes of the expository section.(8) As the music progresses through these sections, the network of fifths with their minor-third partners, first established in measures 1–39 and illustrated in Example 10, gradually extends outward from the initial G/D focal point. Example 11 demonstrates that this movement explores tonal areas that are progressively more “fifths above” D (A, E, and, tentatively in “Development II,” B) as well as those progressively more “fifths below” G (C and F). All the while, the music frequently returns to G (often accompanied by its minor third,

[2.3] Immediately following the music of Example 8, the violin leads into a new passage characterized by two-part counterpoint between the violin and the piano’s right hand. These melodies are underpinned by the Tempo II theme repeated as an ostinato in the piano’s left hand. Example 12 shows the beginning of this section. Note that Copland’s indication of dynamics reinforces the view of the piano’s left hand as accompanimental to the counterpoint in the right hand and the violin. This section continues the G/D pairing via prominent metrical and registral positioning of D and leaps between members of the G-major triad, and also presents a complete “dominant” triad in D in measure 43. This music also features more prominently the

[2.4] As Example 13 shows, this entire complex of G with its major and minor thirds is transposed up a whole step at measure 56, resulting in the similar coloring of A as a pitch center by

|

Example 13. Violin Sonata, I, measures 51—57 (click to enlarge) |

Example 14. Expansion of the network in Development I (click to enlarge) |

Example 15. Violin Sonata, I, measures 78—91

(click to enlarge)

Example 16. Violin Sonata, I, measures 91—107

(click to enlarge)

[2.5] The Tempo II theme returns in altered form in measure 78, as shown in Example 15. In this case, the music focuses upon C, then turns to A at measure 82. C’s association with A (as its third-partner in the network of Example 14) is reinforced by this juxtaposition and by the chain of fifths embedded in the violin melody of measures 82–86. At this point the first expansion of the tonal network is complete: A has now been presented concomitantly with its fifth (E) and its minor third (C). As if to emphasize this point, the music suddenly shifts down a whole step at measure 86 to repeat the Tempo II theme—this time at its original pitch level, stressing G and

[2.6] The following Lyrical Middle Section in measures 94–126 juxtaposes C and E, two pitch centers already charted in the movement’s tonal network but not previously associated with one another. This section’s opening is excerpted in Example 16; its character is well represented by the first portion given here. Throughout, the violin presents a songlike melody punctuated by two- and three-chord piano gestures resembling authentic cadences in C and E. The pairing of C with E suggests the major-third subplot manifested earlier in this movement (and that will receive much greater attention in the sonata’s finale, as described below).

[2.7] Development II (measures 127–200) continues the attention to pitch centers already explored in the network of Example 14.(9) This delay of further tonal exploration may be viewed as a motivator for the climactic crash that culminates this section at measure 193 and leads into the movement’s “Restatements” section at measure 201, as shown in Example 17. The sforzando chords of this crash, though hardly triadic, feature E5 as their highest pitch. When coupled with the melodic Bs and

|

Example 17. Violin Sonata, I, measures 193—204 (click to enlarge) |

Example 18. Violin Sonata, I, measures 205—228 (click to enlarge) |

[2.8] The

[2.9] The pitch centers of the Restatements section are (in order of appearance)

[2.10] The example shows how the Restatements balance the original network’s previous upward extension in a delightfully unexpected way. Now placed as G’s “fifth below” rather than a third-partner to A and E, C is joined in the Restatements section by its fifth below, F, and its minor-third partner,

[2.11] Example 19 summarizes the network of relationships governing the first movement’s tonal organization. Pitch centers, or pitch classes simultaneously vying for centricity, are musically associated with one another in pairs related by perfect fifth or minor third. As the movement proceeds, we find that the initial fifth and third relationships (those of G with D and G with

[3] The Second Movement

[3.1] In comparison with the first movement of the Violin Sonata, the second movement is relatively brief and formally and tonally uncomplicated. It nevertheless embodies the perfect-fifth and minor-third concerns of the first movement, and in fact presents another manifestation of the earlier movement’s tonal network.

Example 20. Pitch centers and formal elements of Copland’s Violin Sonata, II

(click to enlarge)

Example 21. Copland, Violin Sonata, II, measures 1—18

(click to enlarge)

Example 22. Copland, Violin Sonata, II, conclusion (measures 63—69)

(click to enlarge)

Example 23. Copland, Violin Sonata, II, measures 22—45

(click to enlarge)

Example 24. Perfect-fifth relationships among pitch centers of the Violin Sonata’s Lento

(click to enlarge)

Example 25. thirds and fifths among pitch centers in the Violin Sonata’s Lento

(click to see animation)

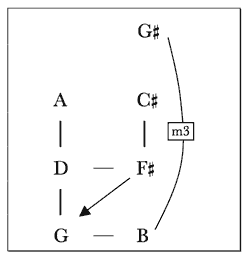

[3.2] Example 20 lays out the thematic and tonal organization of the movement.(12) The curved lines at the top of the example show that this movement exhibits clear formal and tonal symmetry. Its formal design can be summarized as ABBA with similar transitions separating the A and B sections from one another. The only “flaw” in the palindrome of pitch centers is the reflection of G at measure 22 as E at measure 33; this will be taken up in the following analysis.

[3.3] Like the first movement, the second opens with materials that concomitantly point to two potential pitch centers a perfect fifth apart. Example 21 shows the first section of this movement. In this case the piano presents a slow, chant-like melody over droning As in the left hand, and the melody itself comes to rest on A at the end of its first phrase in measure 4.(13) The one-sharp diatonic collection employed here thus suggests the dorian mode. On the other hand, each phrase in the piano, as well as the first violin phrase, begins with D. The section concludes in measure 17 with a D sustained among three octaves of As. This sonority glides into the transition at measure 18, which begins with a familiar motive from the first movement now outlining a D-major triad. Considered together, measures 17–18 seem to suggest that the first section ends by emphasizing D via a second-inversion triad (implied before it is literally present in the transition’s first measure). D and A strike a delicate balance in this opening section, just as G and D were balanced in the prologue of the first movement.

[3.4] The reprise of this chant section at the end of the movement is altered in a few subtle ways, some of which gently bring greater focus to D. The violin begins the reprise at measure 53 by presenting the piano’s melody from measure 2; the piano is now sustaining octave Ds as pedal points (beginning at measure 52) rather than As. At measure 58 the texture reverts to reflect that of the original section, and the octaves on A return in reflection of measure 6. The violin plays an octave displaced version of measure 12 in measure 63 (Example 22), but it is the movement’s closing cadence that provides tonal clarity. Here, the octaves on A that made measure 17 tonally ambiguous are replaced by a quiet, widely-spaced D-major triad in root position.

[3.5] A shared single melody joins the central waltz sections. Example 23 shows both sections. The violin’s melody at measure 22 begins on G5, outlines E minor and G major triads, and then in measure 25 stagnates on G4. Following a short chromatic digression in measures 26–27, it repeats its opening measures and ends this first waltz section with an oscillation between G and A in measures 31–32. This melody’s emphasis on G is supported by certain elements of the piano part: the first harmony of measure 22 is an inverted dominant seventh of G, and the right hand “resolves” to an open fifth on G in the second half of the measure (over an admittedly incongruous

[3.6] The second waltz section, which starts at measure 33, presents the waltz melody in a three-part canon: the piano’s right hand serves as the lead voice (with a lilting off-beat echo an octave lower), followed at the distance of a measure, more or less, by the violin and the left hand of the piano. As the piano’s left hand awaits its entrance with the theme at measure 35, it marks the time by sustaining Es in the piano’s lowest octave. This new underpinning of the melody lends weight to the E-minor triad with which it starts, creating stronger emphasis on E at the beginning of this section. Upon arriving at the other side of the chromatic, tonally ambiguous digression, the three voices perorate on G with upper and lower neighbors, recalling the G focus that characterized the first appearance of the waltz theme.

[3.7] It is possible to link all the pitch centers of the second movement in a chain of perfect fifths, as shown in Example 24. The thicker line connecting D to A represents the musical coupling of these fifth-related pitches in the first and last sections of the movement. Unlike G/D and A/E, D and A are directly juxtaposed in the music framing the movement. One might say that D/A is the focus of this movement in a sense similar to that in which G/D served as the focus of the first movement. In both cases, the constituent pitch classes of the perfect fifth are cast in juxtaposition with one another in the beginning and final sections of their movements, and the pitch centers explored in the movements’ interiors relate to this perfect fifth via perfect fifths (with the assistance of minor thirds). Moreover, the D/A focus of the second movement is itself a perfect-fifth transposition of the first movement’s G/D focus. The pairing of pitch centers a fifth apart, first seen in the opening and closing sections of these movements, is not only aligned with the tonal organization of the individual movements but also parallels the tonal logic linking the movements to one another.

[3.8] The vertical lines connecting G to D and A to E in Example 24 are potentially misleading—though they join pitch centers of the second movement separated by perfect fifths, the constituent pitch classes thus joined are not clearly paired in the surface of this movement. That is, there is no musical reason in this movement for linking G with D or A with E. On the other hand, E and G are clearly linked musically with one another through their associations with the waltz theme and sections. This minor-third pairing is also, of course, in the spirit of the sonata’s first movement. In that movement, pitch centers musically linked to others a perfect fifth away also had the potential to bear a minor-third partner (e.g., G’s association first with D and then with

[3.9] Representing succinctly in a diagram all the fifth and third relationships suggested by the second movement in two dimensions is problematic, but Example 25 represents one attempt. The curved lines of this example stand in for the vertical lines that connected G to D and A to E in Example 24. In all previous representations of the tonal networks in the Violin Sonata, movement vertically on the network represented movement up or down by perfect fifth, and movement to the right represented movement up by minor third. In Example 25, by contrast, the vertical perfect-fifth space is “bent” at the G/D and A/E junctures—since these fifths are not emphasized in the music of the movement—so as to illuminate the more salient minor-third relationship between E and G.

[3.10] The approach to pitch centricity exhibited in the Violin Sonata’s second movement reflects the first movement’s preoccupation with perfect fifth and minor third relationships. In addition, the G/D focus of the first movement relates logically to the D/A focus of the second inasmuch as the latter is a transposition of the former by the crucial interval of the perfect fifth. The foregoing analysis shows that these movements belong together tonally; put another way, the treatments of pitch centers and other elements of the music’s surface parallel the movement’s organization of pitch centers at the largest levels. The third movement, in reflection of its exuberant and buoyant character, expands upon the now-established tonal conventions of the first two movements before summarizing the sonata’s tonal endeavors in its coda.

[4] The Third Movement

[4.1] Pollack convincingly describes the form of the Violin Sonata’s third movement as follows:

[4.2] ...a binary (or perhaps binary sonata) form (AA′). The movement’s first half successively states a scherzolike theme; a slower and more intimate melody; a fast, spirited tune; a short folklike interlude (over a static harmony); and a poignant closing theme.... The finale’s second half more or less recapitulates its first half, with the exception of the folklike section, an omission balanced by the unexpected reappearance of that episode’s sauntering accompaniment in the otherwise somber coda. This coda—a brief reprise of the work’s very opening—comes to rest on a stunning sonority involving harmonics in the violin and widely spaced intervals in the piano (Pollack 1999, 385).

[4.3] Example 26 parses the formal design of the finale after Pollack’s description. The arrows on the diagram show how four of the five sections of the A portion are indeed reprised in A′. Pollack’s “folklike interlude” at measure 96 is replaced in A′ by one more statement of the movement’s opening scherzo theme, followed by a climactic stratification of the “spirited” theme over the scherzo in two-part imitation. The accompaniment for the measure 96 interlude returns in the finale’s coda.

[4.4] Pollack’s brief summary of this movement does not take into account its pitch centers (also shown in Example 26). By considering how these pitch foci relate to one another, especially in light of the tonal concerns of the previous movements, it becomes clear that this finale shares the rest of the sonata’s preoccupation with tonal elements related in networks of perfect fifths. Simultaneously, the third movement provides a new variation on those tonal concerns: instead of accentuating minor-third relationships alongside those of perfect fifths, the finale places greater stress upon major-third partnerships together with perfect fifths. This emphasis of major-third associations was first suggested in the opening movement (via its Lyrical Middle Section, not to mention the violin’s very first melody) and is itself reflected in elements of the third movement’s musical surface. The following analysis examines the use of major-third and perfect-fifth connections to align this finale’s pitch centers with its own musical events and to link it with the preceding movements.

[4.5] The significance of major-third connections to this finale is introduced by its first two pitch centers, G and B. Examples 27 and 28 present the incipits from the opening sections that put forth these pitch centers, both of which are posited modally. The movement opens with a strong focus on G: the repeated octaves in the piano and the frequent stresses on G and its “dominant,” D, make that clear.

|

Example 27. Copland, Violin Sonata, III, measures 1—13 (centered on G) (click to enlarge) |

Example 28. Copland, Violin Sonata, III, measures 42—29 (centered on B) (click to enlarge) |

[4.6] The underscoring of B as a pitch center at measure 42 is less ardent. The section begins with a landing on a B-minor triad, and the piano’s pulsing eighth-note accompaniment is rarely without the pitch class B. The violin’s pandiatonic play does take some emphasis away from B as a pitch center, but it still allows for the apprehension of B aeolian.(15)

[4.7] Though this movement hardly takes on the form of a sonata, Copland has granted these opening two sections qualities reflecting those one might find in a traditional sonata-allegro form—an aggressive, marcato-like first theme followed by a soaring, slower-moving second theme. The sections’ respective approaches to pitch centricity reflect this dichotomy, thus suggesting (in addition to their temporal juxtaposition at the movement’s onset) that B might be regarded as a partner to G. In this way the significance of the major-third relationship is first established in this movement. We will see major thirds, and especially this G–B pairing, emerge as an essential element of the finale’s tonal organization.

Example 29. Copland, Violin Sonata, III, measures 76—84 (violin only)

(click to enlarge)

Example 30. Network of pitch centers used in the A part of the finale

(click to enlarge)

[4.8] Example 29 shows the first version of the “spirited” theme from measures 76–84 as it centers on D. The melody itself places great emphasis on other members of the D-major triad before finally approaching D itself (via an ascending fourth from A) in measure 81. The piano presents truncated versions of this melody beginning in measure 84 and measure 91, transposed to point to A and G respectively, as offbeat pedal points reinforce these tonics and the violin provides a softer obbligato built from fragments of the same theme. In light of the preceding movements, it is easy to reconcile this use of D and A as pitch centers via perfect fifth links. After establishing its main focus on G and the secondary importance of its major third, B, the finale reaches upward by fifths from its starting point (as in previous movements) to D and then to A. It then returns to G and remains there for the rest of the A portion of the movement’s form.

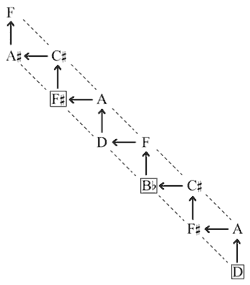

[4.9] In analogy to the networks used in discussion of the first two movements, Example 30 maps the tonal forays of the finale thus far. In contrast to previous examples showing tonal networks in this sonata, this example plots major-third relationships, rather than minor thirds, along its horizontal axis.(16) This adjustment reflects the finale’s concern with major thirds, which will become more crucial as the network grows to accommodate subsequent pitch centers. Another significant difference in the tonal structure of this movement is that it focuses on a single pitch center, G, rather than hinging upon a pairing of perfect-fifth related pitch centers (like G/D in the opening movement or D/A in the Lento). Moreover, Example 26 shows that G is by far the most oft-asserted pitch center of the movement. D’s role in this movement is significant, as subsequent discussion will show, but its presence does not breed tonal ambiguity with G in the same ways that certain fifth relationships did earlier in the sonata.

[4.10] Example 31 shows how the beginning of A′ continues the finale’s new emphasis of major thirds. This example displays the end of the “poignant” slow theme, which also concludes the A portion of the movement at measure 115. The plaintive melody and its accompaniment both stress G alongside B as the A section closes, foreshadowing the impending change in centricity. After presenting Bs in the context of G’s governance over and over again in this slow theme, the shift to B centricity at measure 115 takes on a magical quality.

|

Example 31. Copland, Violin Sonata, III, measures 112—125 (pitch centers indicated in parentheses) (click to enlarge) |

Example 32. Copland, Violin Sonata, III, measures 159—173 (pitch centers indicated in parentheses) (click to see animation) |

Example 33. New pitch centers of A’ arranged in consecutive perfect fifths and so as to emphasize the minor third /B

(click to enlarge)

Example 34. Comparison of pitch-center networks between movement II and A’ of movement III

(click to enlarge)

[4.11] The scherzo theme is varied with octave displacements as it returns in measure 115, and then shifts to

[4.12] B is not musically affiliated with

[4.13] Example 34 shows that the A′ pitch centers, and the set of musical affiliations linking them with one another, have a deeper parallel with the pitch centers of the sonata’s second movement. The left side of Example 34 replicates Example 25, which showed the minor-third and perfect-fifth relationships among the four pitch centers touched upon in the second movement. The right side of Example 34 duplicates Example 33b. The two networks shown in Example 34 are isomorphic. That is, the relationships among the four pitch centers of the second movement are duplicated in those of the A′ portion of the finale. This is true both in an absolute intervallic sense (i.e., in both cases the four pitch centers can arranged in pitch space as a stack of perfect fifths, the top and bottom of notes of which are separated by a minor third) and, more significantly, in the ways the pitch centers relate musically to one another. In both networks the pitch centers related by minor third present the same thematic material in succession —the waltz in the second movement and the scherzo in the third. Meanwhile, the other pitch centers in each network are emphasized as a pair via other musical means (the D/A tonal ambiguity in the outer sections of the second movement and the eliding of

[4.14] The appearance of

[4.15] The presentation of these themes in G and D followed by their recapitulations in B and

[4.16] Upon returning to G centricity at measure 172, the finale remains focused on G until its conclusion. This shift to G, shown in Example 32, is one of the sonata’s most abrupt. The

[4.17] This accentuation of the juncture between

[4.18] By juxtaposing tonal and thematic elements from the entire sonata, the coda crystallizes the entire composition’s thematic and tonal concerns. Example 37 presents this striking passage. The coda’s opening theme references the D-

[4.19] The coda also contains links with the previous music that become clear only in view of the tonal issues brought to light by the preceding analysis. The closing chord, for instance, is in one sense simply a root-position G-major triad—arguably the appropriate final sonority of a movement whose overall tonal focus is on G. On the other hand, the striking spacing and distribution of this chord’s members, already mentioned in Pollack’s brief analysis, can be seen to represent the fifth- and third-partnering that has proven crucial to the entire sonata. Above the piano’s G1, the violin is given a wide registral berth so it can present G uncluttered alongside its perfect fifth, D, manifested here as the twelfth G3/D5. The D5, which is most practically performed as a harmonic, takes on an additional quality of “belonging” to the G3—the wide interval and the typical performance of both notes without vibrato causes the two pitches to blend almost as if the D5 were nothing more than an overtone of the G3.(17) This final partnering of G with D symbolizes this sonata’s concern with fifths and specifically with this fifth.

[4.20] Meanwhile, the piano’s right hand mimics the violin’s fifth-partnering in this chord with a similar coordination of G with its major third, B. G5 and B6 crown this sonority, isolating this dyad timbrally and registrally just as G3 and D5 are together isolated in the violin. This privilege of the major third G-B is only appropriate given the significance of the major third (indeed, this major third) to the finale’s tonal makeup. (Recall also how the importance of the major third was predicted in the first movement, and that

Example 38. Analysis of finale, measures 223—226 (violin only

a. (Segmentation of melody)

(click to enlarge)

[4.21] Example 38a dissects the coda’s final melody. The level of chromaticism in these measures is unusual for this work, but the harmonies thus suggested spin a web of associations in congruence with the tonal concerns of the entire sonata. First, this melody uses major thirds to generate a sequence: its second measure is a direct transposition of the first down a major third, and the third repeats the transposition while displacing the quarter notes up an octave. The melodic unit being sequenced is itself made up of what are, in this work’s context, familiar intervals: a perfect fifth, a minor third, and a perfect fourth (i.e., an inverted perfect fifth). In addition, each unit can be reconciled as a major seventh chord as noted on the example. These seventh chords’ roots themselves have held significance in the sonata. D, of course, is the perfect-fifth partner of G, as well as the main focus of the second movement.

Example 38. Analysis of finale, measures 223—226 (violin only)

b. (Melody mapped onto tonal network)

(click to enlarge)

[4.22] In addition to focusing attention to crucial pitch classes as chordal roots, the melody of measures 223–25 distills the sonata’s intervallic concerns in its note-to-note successions. The melody’s intervallic content creates a cycle of ordered pitch-class intervals, alternating between 7s (ascending perfect fifths) and 9s (descending minor thirds). Example 38b maps this pattern onto the now-familiar tonal network of perfect fifths and minor thirds, illustrating how this cycle generates the three major seventh chords that are musically marked by motivic repetitions in these measures.(18) The dotted lines in this figure show that any two moves in this cycle result in ordered pitch-class interval 4, an ascending major third. This melodic sequence thus keenly reinforces the work’s structural focus on fifths alongside minor, and then major, thirds.

[4.23] Finally, the melody concludes with a series of descending perfect fifths ending at B, which then falls a final major third to G. This chain of fifths anchored by B reflects the pitch centers newly explored in the A′ part of the finale. The ultimate descending third from B to G has obvious parallels in light of the previous discussion; in fact, B-G is the closing gesture for each of the violin’s three melodic phrases in this coda.

[4.24] The coda thus mirrors not only the tonal concerns of the finale but of the entire sonata. It casts in microcosm the pitch centers of greatest import to the work and the intervals between them. It constitutes a fitting close to the whole work by recapitulating, in a miniature fashion, its significant tonal and thematic elements.

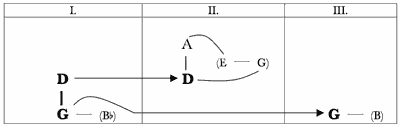

[5] Synthesis of the Three Movements

[5.1] Previous analysis has already highlighted some of the tonal commonalities linking these movements; this concluding section summarizes the resulting tonal structure of the complete work in light of that analysis. Example 39 represents the main pitch centers of the three movements with bold print and posits some connections between them. The first movement opens and closes with tonal ambiguity balancing G and D. Locally, this ambiguity suggested the potential for partnering pitch classes related by perfect fifth, thus giving rise to the A/E and F/C partnerships that extended this movement’s tonal structure upward and downward as shown in Example 19. Nevertheless, the G/D ambiguity framing the entire movement remains unresolved at its conclusion. A view of the whole sonata shows that this ambiguity is worked out in subsequent movements. The Lento second movement takes up the D as its main pitch center, though that focus is itself blurred in the movement’s outer sections by references to A centricity. The second movement’s tonal organization thus aligns with the first’s by taking up D as its focal point even as it blurs that focus with another potential pitch center a perfect fifth away, in analogy to the G/D issue of the opening movement. The finale subsequently centers on G, the other pitch central to the first movement.

[5.2] The third movement also makes use of fifth relationships, as already described (though not shown in Example 39), but from a larger perspective works in consort with the other movements to replicate the Lento’s D/A resolution at the level of the entire sonata. After the second movement puts forth a D/A ambiguity in correlation to the first movement, and even leans towards A at first, it eventually settles on the lower note of this fifth, D, as its final and “main” pitch center. Similarly, the sonata itself begins with a G/D fifth ambiguity in the first movement, but eventually comes to rest on that fifth’s lower note, G, in the third movement, after giving some intermediate attention to D in the Lento. The notion of tonal ambiguity between fifth-related pitches that is eventually settled in favor of the lower note of the interval plays out at multiple levels in this work.

[5.3] Tonal associations by third also recur throughout all three movements. Example 39 indicates some of the third relationships that have significance to the work’s tonal structure. The linking of

[5.4] Example 39 also represents the structural role played by the major-third partnering of G and B in the last movement. The finale uses the major third G-B to help define the two large parts of its binary form, even as its A′ portion makes use of a minor-third relationship to help generate its internal organization. Just as the first movement foreshadows the later significance granted to the major third, the finale reminisces upon the minor third’s value to previous movements even as it embodies the major third’s structural import. In light of these observations, the coda’s final reference to

[5.5] The Sonata for Violin and Piano thus exhibits similar tonal concerns and approaches across all of its movements. In various ways, the movements replicate elements of one another’s tonal structures, but they also unite to create a larger-level structure that aligns with its constituent parts. As much as any Copland work, the Violin Sonata demonstrates how the traditional tonal relationship of the perfect fifth can be recast to generate a fresh, unprecedented approach to large-scale tonal organization.

[6] Conclusion

[6.1] Commenting on the Philadelphia premiere of the Violin Sonata, Vincent Persichetti noted, “The effect of one triad harmony pulling against another tightens the band of harmonic tension in such a way that its numerous releases into clear and pure places is splashed with vividness” (Persichetti 1944, 47). This colorful summary of the work’s tonal language captures something of the music’s juxtaposition of fifth- and third-related pitch foci, one or both often supported with triadic references. It is no small wonder that, only a decade later, Arthur Berger credited Copland with “the rehabilitation of the triad, the discovery of new harmonic possibilities afforded by its franker use” (Berger 1953). This music’s use of triads and triadic progressions is essential to the pitch foci that emerge throughout, and indeed the pitting of triads against a contradictory bass in the sonata’s opening measures gave rise to the foregoing perspective of its approach to tonal organization that is at once unique yet still based on fifth relationships.

[6.2] Copland himself espoused the view that “the freer interpretation of the ordinary tonal system now in use opens a far from exhausted field of possibilities” (Copland 1941, 55). Interval class 5 is certainly a key element of that “ordinary tonal system” through its saturation of the diatonic set and its historical role in defining the tonic/dominant relationship. In addition to appropriating the perfect fifth to develop the musical flavor now often described as “American,” the Violin Sonata shows the composer setting up dichotomies between fifth-related pitch classes that have consequences for the tonal structure of the entire work. Fifth relationships at the largest levels also typify traditionally tonal music, but Copland’s innovative employment of perfect fifths, and specifically the opening G/D duality as progenitor, to spin out this sonata’s tonal architecture is unparalleled in functional tonality.

[6.3] As noted near the beginning of this essay, fifth-based ambiguities color several of Copland’s compositions from his mature style. The first of the Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson, the Third Symphony’s scherzo, and the conclusion of Quiet City are examples from the 1940s. In this light, the Short Symphony from 1933 might be viewed as an antecedent to the Violin Sonata (its opening also puts forth an ambiguous dual focus on G and D).(19) The Violin Sonata analysis presented above suggests it is an oversimplification to state that Copland’s best-known style emphasizes fifths. In fact, ic 5 impacts this work’s broadest levels of tonal organization in ways reflective of its role in the music’s basic harmonic vocabulary. If the Violin Sonata is emblematic of Copland’s structural treatment of perfect fifths, then investigation of other works similarly imbued with ic-5 emphases—like those surveyed in Examples 1–5—will aid in clarifying this composer’s style from a structural perspective.(20) By becoming familiar with this perspective, we can begin to see, through his own eyes, that “field of possibilities” Copland saw in the “ordinary tonal system.”

Stanley V. Kleppinger

227 Westbrook Music Building

University of Nebraska-Lincoln

Lincoln, NE 68588-0100

skleppinger2@unl.edu

Works Cited

Bailey, Robert. 1985. “An Analytic Study of the Sketches and Drafts.” In Prelude and Transfiguration from “Tristan and Isolde,” by Richard Wagner, 113–48. New York: W. W. Norton.

Berger, Arthur. 1953. Aaron Copland. New York: Oxford University Press.

Brower, Candice. 2008. “Paradoxes of Pitch Space.” Music Analysis 27, no. 1: 51–106.

Brown, Stephen C. 2003. “Dual Interval Space in Twentieth-Century Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 25, no. 1: 35–57.

Burkholder, J. Peter, Donald J. Grout, and Claude V. Palisca. 2006. A History of Western Music, 7th ed. New York: W. W. Norton.

Cohn, Richard. 1996. “Maximally Smooth Cycles, Hexatonic Systems, and the Analysis of Late-Romantic Triadic Progressions.” Music Analysis 15, no. 1: 9–40.

—————. 1997. “Neo-Riemannian Operations, Parsimonious Trichords, and their Tonnetz Representations.” Journal of Music Theory 41, no. 1: 1–66.

Copland, Aaron. 1941. Our New Music. New York: McGraw Hill.

Copland, Aaron, and Vivian Perlis. 1984. Copland: 1900 through 1942. New York: St. Martin’s/Marek.

—————. 1989. Copland since 1943. New York: St. Martin’s/Marek.

Creighton, Stephen David. 1994. “A Study of Tonality in Selected Works of Aaron Copland.” Ph.D. diss., University of British Columbia.

Daugherty, Robert Michael. 1980. “An Analysis of Aaron Copland’s Twelve Poems of Emily Dickinson.” D.M.A. diss., Ohio State University.

DeVoto, Mark. 2004. “‘The Keel Row,’ Gigues, and Bifocal Tonality.” In Debussy and the Veil of Tonality: Essays on his Music, 126–43. Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press.

Gollin, Edward. 1998. “Some Aspects of Three-Dimensional Tonnetze.” Journal of Music Theory 42, no. 2: 195–206.

Hyer, Brian. “Reimag(in)ing Riemann.” 1995. Journal of Music Theory 39, no. 1: 101–138.

Kleppinger, Stanley V. 2009. “A Contextually Defined Approach to Appalachian Spring.” Indiana Theory Review 27, no. 1: 45–78.

—————. 2010 [forthcoming]. “The Structure and Genesis of Copland’s Quiet City.” twentieth-century music 7, no. 1.

Kaminsky, Peter. 1989. “Principles of Formal Structure in Schumann’s Early Piano Cycles.” Music Theory Spectrum 11, no. 2: 207–25.

Kinderman, William. 1988. “Directional Tonality in Chopin.” In Schenker Studies, ed. Jim Samson, 59–75. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kinderman, William, and Harald Krebs, eds. 1996. The Second Practice of Nineteenth-Century Tonality. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Krebs, Harald. 1991. “Tonal and Formal Dualism in Chopin’s Scherzo, Op. 31.” Music Theory Spectrum 13, no. 1: 38–60.

Lerdahl, Fred. 2001. Tonal Pitch Space. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lewin, David. 1987. Generalized Musical Intervals and Transformations. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lewis, Christopher. 1984. Tonal Coherence in Mahler’s Ninth Symphony. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press.

—————. 1996. “Gustav Mahler: Romantic Culmination.” In German Lieder in the Nineteenth Century, ed. Rufus Hallmark, 218–49. New York: Schirmer.

Mathers, Daniel. 1989. “Closure in the Sextet and Short Symphony by Aaron Copland: A Study Using Facsimiles and Printed Editions.” M.M. thesis, Florida State University.

Mellers, Wilfrid. 2000. “Aaron Copland, Emily Dickinson, and the Noise in the Pool at Noon.” Tempo 214: 7–18.

Morris, Robert. 1998. “Voice-Leading Spaces.” Music Theory Spectrum 20, no. 2: 175–208.

Newlin, Dika. 1978. Bruckner, Mahler, Schoenberg, 2nd ed. New York: W. W. Norton.

Persichetti, Vincent. 1944. “Modern Chamber Music in Philadelphia.” Modern Music 22, no. 1: 47–49.

Pollack, Howard. 1999. Aaron Copland: The Life and Work of an Uncommon Man. New York: Henry Holt.

Smith, Peter H. 2009. “Harmonies Heard from Afar: Tonal Pairing, Formal Design, and Cyclical Integration in Schumann’s A-minor Violin Sonata, op. 105.” Theory and Practice 34: 47–80.

Starr, Larry. 2002. The Dickinson Songs of Aaron Copland. Hillsdale, NY: Pendragon Press.

—————. 2005. “War Drums, Tolling Bells, and Copland’s Piano Sonata.” In Aaron Copland and His World, ed. Carol J. Oja and Judith Tick, 233–44. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Stein, Deborah. 1985. Wolf’s Lieder and Extensions of Tonality. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press.

Straus, Joseph. 1982. “Stravinsky’s Tonal Axis.” Journal of Music Theory 26, no. 2: 260–90.

Von Glahn, Denise. 2003. The Sounds of Place: Music and the American Cultural Landscape. Boston: Northeastern University Press.

Footnotes

1. Larry Starr reads this sonata as a wartime piece; by omitting both members of the motto chords’

Return to text

2. The problem of identifying a pitch center for this music is demonstrated in the literature. Starr says, “we may meaningfully call ‘Nature, the gentlest mother’ a song ‘in’ E-flat and pinpoint the manner in which its music establishes, moves away from, and returns to this E-flat pitch center” (Starr 2002, 35), whereas Robert Daugherty suggests that “although the key signature fits E-flat major, the consistent emphasis on B-flat makes it more likely that the introduction and A sections of the piece are in a transposed mixolydian [i.e., centered on

Return to text

3. See Von Glahn 2003, 120; Pollack 1999, 332; and Creighton 1994, 111.

Return to text

4. In this sense, this tonal pairing shares commonalities with Robert Bailey’s “double-tonic complex” (Bailey 1985, also appropriated by Lewis 1984) and Joseph Straus’s “tonal axis” (Straus 1982). As is the case with those theoretical constructs, the dualities charted in the analysis below consist of pairs of perceptually emphasized pitch classes set forth as pitch centers (often reinforced as triadic roots) whose interrelationship is reflected in large-scale tonal structure. An important difference is that both of these theories focus on pairings of tonics related by thirds, whereas Copland’s music explored here puts forth dual pitch-class emphases that are related by fifths (as well as thirds). In addition, Straus’s tonal axis hinges more strictly upon musical emphasis of the two third-related “tonic triads” as a fused harmonic entity; e.g.,

Return to text

5. The three authentic-cadence gestures, in conjunction with the preceding stasis on G in the piano (until measure 26), constitute a simple tour of the four stations of this network.

Return to text

6. This network can be plotted in a Dual Interval Space (DIS) as conceived by Stephen Brown. A DIS is “a two-dimensional model of pitch-class space” (Brown 2003, 35) in which each axis corresponds to a specific interval class. This network exists in Brown’s ic-3/ic-5 DIS; that is, movement along the x-axis manifests motion by ic 3 and movement along the y-axis manifests ic 5. The DIS is, of course, part of a long-standing practice of mapping tonal motions and relations in conceptual spaces of two or more dimensions. This practice extends back to Oettingen’s and Riemann’s Tonnetze, and has been used more recently by Candice Brower (2008), Richard Cohn (1996), Edward Gollin (1998), Brian Hyer (1995), and Fred Lerdahl (2001) (among many others) to represent analysis of common-practice-era music, and by Brown (2003), Cohn (1997), David Lewin (1987), and Robert Morris (1998) (again among many others) for analysis of post-tonal music.

Return to text

7. In fact, F is the least stressed pitch center of the four in this most basic version of the tonal network, and seems to be present simply to pin down this corner of the interlocking fifth/third relationships. This somewhat lower level of significance granted to F is replicated as the network is expanded later in the sonata. See the discussion of Example 19.

Return to text

8. Pollack’s summary of this form parallels that presented here except that he regards the “Lyrical Middle Section” as the movement’s secondary theme; in this perspective the development does not begin until measure 127 and my “Development I” is subsumed as part of the exposition (Pollack 1999, 384–85).

Return to text

9. A possible exception might be the music beginning at measure 173, which, as Example 11 suggests, might point to B for a few bars. If B is in fact perceived as a pitch center here, it can be reconciled to the present analysis by regarding it as a tentative, but not wholly realized, extension of the network upward one more fifth from E.

Return to text

10. Brown’s Dual Interval Space (DIS) operations (Brown 2003) can model concisely the differing ways in which the tonal network is expanded upward and downward in this movement. If the network of Example 9 is construed as an ic-3/ic-5 DIS, the upward extension of the network earlier in the movement constitutes the transpositional operation T(0,2) (i.e., rightward movement in the space zero spaces and upward movement two spaces). The downward extension of the network in the Restatements section manifests Brown’s inversion operation I(—,−1) (i.e., “flipping” the original G/D/

Return to text

11. The composer seems to go out of his way to de-emphasize

Return to text

12. Pollack does not address the form of this movement in his biography of Copland (Pollack 1999). The composer himself calls the Lento “a simple ABA form” (Copland and Perlis 1989, 23).

Return to text

13. Measure 6 to this listener suggests a similar arrival on A at the phrase’s end. The right hand’s G in this bar decays for two long beats before the As are re-struck in the left hand. As a result, the G sounds as though it resolves modally to A (in a displaced octave) rather than continuing to be sustained over the As as they are repeated.

Return to text

14. Considered another way, the piano’s sonorities in the first waltz section also reflect this work’s preoccupation with perfect fifths. The chords of measure 22 (repeated in measure 23), via their registral dispositions, might be regarded as D and G chords (a triad and an open fifth respectively) stratified over C and F. These four pitches can be readily arranged into a series of descending perfect fifths: D-G-C-F. The next note in this series,

Return to text

15. Lest the reader think that tonal ambiguity at measure 42 is too rampant to suggest a pitch center at all in this section, it is worth noting that B centricity becomes gradually clearer following the music of Example 28. Indeed, by measure 61 the violin achieves a sort of stasis on fanfare-like B-major arpeggiations as the piano accompanies with a quasi-ostinato pattern using only B and

Return to text

16. This network thus manifests Brown’s ic-4/ic-5 DIS.

Return to text

17. Though Copland does not indicate that the D5 is to be performed as a harmonic, performing this note by pressing down the D string at its midpoint (the only other possible way to execute this double-stop) while maintaining the specified pianissimo dynamic is certainly more difficult. In addition, the performance of this double-stop without vibrato tends to reinforce the intimate morendo character suggested by the sonata’s conclusion. For these reasons, every violinist I have consulted performs the D5 as a harmonic without vibrato, and I have not uncovered a recording that does otherwise. My thanks go to Davis Brooks, Frank Felice, David Neely, and the other string players (and performers of this sonata) who have assisted in analyzing the performance issues surrounding this chord.

Return to text

18. The 7/9 cycle of ordered pitch-class intervals generates a hexatonic collection (set class (014589)), which—as highlighted in Example 38a—contains three major seventh chords related by T4, any two of which hold two pitch classes in common.

Return to text

19. In this regard see Mathers 1989.

Return to text

20. See Kleppinger 2009 and Kleppinger 2010.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2011 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by John Reef, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits: