Review of David Damschroder, Harmony in Schubert (Cambridge University Press, 2010)

Gordon Sly

Copyright © 2012 Society for Music Theory

[1] David Damschroder’s provocative and expansive Harmony in Schubert offers an approach to harmonic process and meaning that confronts our pedagogy, illuminates elusive details of Schubert’s harmonic language, and engages a diverse body of Schubert scholarship in contexts provided by a number of the composer’s best-known works.

[2] In part one, Damschroder presents his methodology, taking us through chapters on harmonic and linear progressions, common prolongations and successions, and chords built on ![]()

[3] Damschroder’s analytical sensibility is thoroughly Schenkerian, but he grafts onto this an approach to Schubert’s harmonic language, and an analytical nomenclature, derived from the nineteenth-century Stufentheorie tradition. Jettisoned from our standard-practice Roman-numeral/figured-bass alloy are, most notably, indications of secondary or applied function and figured-bass numbers used to indicate chordal inversion. For example, an A-major triad in G major is not V/V, but ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]() II

II

Example 1

(click to enlarge)

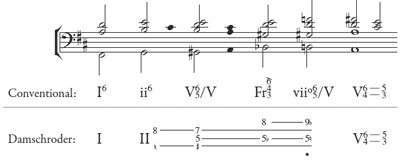

[4] An advantage of this approach is that it can often provide particular insight into harmonic process. Consider the succession of chords given in Example 1. Directly beneath the staff is a conventional harmonic description. Note that the analysis using Damschroder’s approach, given beneath that, preserves the “parent” chord designation (II) through the chromatic evolution of the supertonic harmony, and in so doing illuminates a process that is obscured—or at least deemphasized—by the more usual nomenclature. Consider further that in a given context these chords may not occur adjacently, but rather may give shape to a significant musical span, with each stage in the evolution connected to the next by other chords that arise through voice-leading motions. In such a case, the process of an evolving supertonic harmony would almost surely be lost on conventional analysis, making Damschroder’s method all the more penetrating.

[5] In the book’s preface, Damschroder calls for the general adoption of this new approach to harmony in the undergraduate classroom, appealing to our “pedagogical branch to develop the resources to align itself better with the speculative branch” (x). It is an intriguing idea, given the benefits described in the context above. Of course, benefits and shortcomings can reverse polarity with a change of context. An analytical approach, like Damschroder’s, that accounts for altered tones chromatically in the home key is less sensitive to context than one that explains such tones diatonically in a secondary key if, in fact, that context involves modulation to the secondary key. Damschroder eschews the practice of labeling tonicizations with secondary-dominant chords because he feels that this creates the misleading impression of a shift of tonal center. While his objection is well-taken, still, the difference between tonicization and modulation is quantitative, not qualitative. The processes themselves, that is, are identical; differences between the two are those of emphasis, placement, and/or duration. If a given context does involve such a shift—say, a modulation to the key of the dominant—then it is important for our students to know, and to indicate analytically, that

[6] In chapters 5 through 12, Damschroder engages the work of a number of scholars who have written about Schubert’s music: David Beach, Suzanna Clark, Richard Cohn, Charles Fisk, Robert Hatten, David Kopp, Lawrence Kramer, David Lewin, and Richard Taruskin. This extended sequence of juxtaposed competing analyses will for many readers represent the volume’s chief appeal. The presence of a contending analytical perspective tends to throw its own particular light on its rival. It prompts the reader to approach analytical explanations more keenly, with a measure of skepticism, and to consider carefully the assumptions upon which an analysis rests. It admonishes us to keep in mind that any analytical approach carries specific implications and constraints—that analytical claims have consequences. It can also be a very good thing to be reminded that two convincing and yet contradictory analytical accounts of a piece are possible.

[7] What Damschroder wants, of course, is for deficiencies or lapses that he finds in his colleagues’ analyses to endorse his approach. There are three innate encumbrances to this strategy. First, though he has done what he can to represent opposing perspectives fully and accurately, such a format cannot possibly manage this with uniform success. While the battle lines are certainly drawn well enough, a textured image of the alternative view will require that one consult its full context—something that Damschroder recommends in his preface. Second, not all of these authors are examining Schubert’s music, as Damschroder is, through lenses ground primarily to bring harmonic matters into focus. And third, it is the dispute between analytical methods that is at issue here, rather than the skill of any individual analytical application of them, yet Damschroder’s attention is often diverted by the latter. Where contrasted approaches can be well represented, where harmonic questions are front and center, and where analytical expertise is (expressly or tacitly) acknowledged, this organizational procedure furnishes the most compelling result. Where one or another does not obtain, it is less successful.

[8] The effectiveness of Damschroder’s engagements with the work of Kopp and Cohn, for example, springs from the common focus that he shares with these authors. All three advance harmonic theories designed to account for the chromatic subtleties of nineteenth-century music, theories that reject conventional harmonic analysis and develop in its stead relationships and nomenclatures calibrated to the sensibilities of this literature. The same issues, then, are at stake for all. Yet their orientations are sharply divergent. Kopp’s sensitivity to adjacent harmonic relationships, and, in the present context—an analysis of the song “Die junge Nonne” (Kopp 2002, 254–63)—to third-related harmonies in particular, contrasts Damschroder’s attention to the evolving states of single harmonic functions. Both are counterpoised by Cohn’s (1999) approach, which privileges shared tones and efficiency of voice-leading between harmonies, rather than their position relative to a diatonic set or tonal center. So antithetical are Cohn’s and Damschroder’s methods that, brought to bear on the opening movement of Schubert’s

[9] The apposition of Damschroder’s and Beach’s readings of the opening movement of the “Trout” Quintet is particularly engaging, in part because the main issue of contention—the movement’s subdominant recapitulation—is so closely circumscribed. For Beach 1993, the central issue is how this harmony relates to the dominant harmonies that precede and follow it. Damschroder’s painstaking attention to harmonic process leads him to view this arrival as a consequence of the layered tonal trajectories that shape the development, and to interpret its role in the movement in that light. I am especially drawn to these analyses because they intersect with my own work. In a pair of sequenced essays (Sly 2001 and Sly 2009), I argue that a prominent thread in Schubert’s evolving sonata-form practice involved his efforts to reconcile an emerging recognition of, and desire for, the structural resolve provided by a coordinated tonal and thematic recapitulation with his penchant for modulatory and modal symmetry between exposition and recapitulation, which often defeated that coordinated return by requiring that the recapitulation begin away from the tonic. What Schubert seeks, I maintain, is a seeming impossibility—a recapitulation that begins both away from the tonic (in its broad key design), and in the tonic (structurally). I conclude that his eventual solution is to set the off-tonic thematic return as part of a tonal trajectory that is itself subsumed by a larger trajectory that subsequently leads into the structural return of the tonic. In this way, the listener is aware at the point of thematic return that the deeper recapitulation is yet to come. Damschroder’s analysis illustrates precisely this. Dominant E is prolonged from the second tonal area of the exposition across to the structural tonic return at measure 249. The overarching tonal trajectory follows a chain of major thirds, dividing the dominant octave symmetrically: the C major that begins the development moves sequentially in descending perfect fifths, reaching

[10] At the other end of the spectrum, the least successful chapter is that in which he engages (“bludgeons” might be a better choice) Richard Taruskin (2005) on the opening movement of the “Unfinished” Symphony. Its format is straightforward: Damschroder presents a highly nuanced and idiosyncratic harmonic and motivic analysis of the movement, and then excoriates Taruskin for failing to recognize many of its findings. It’s a little like watching a person trying to pick a fight with someone whose back is turned; one wants to look away. That the context for Taruskin’s commentary is a musicology textbook, aimed at a very specific readership; that an analysis even approaching the depth or sophistication of Damschroder’s would be out of place here, even if its author were capable of it—none of this causes Damschroder to palliate his criticism in any way. The presence of the Taruskin provides a forum for Damschroder’s analysis—and it is a wonderful analysis—but this is hardly a presentation of contending viewpoints.

[11] In sum, Damschroder’s Harmony in Schubert represents a valuable and welcome contribution to a subject whose richness is more widely acknowledged and enjoyed than it is understood. Both his sophisticated analytical approach to Schubert’s harmonic practice and his direct engagements with so much Schubert scholarship will surely prompt further study.

Gordon Sly

Michigan State University – College of Music

102 Music Building

East Lansing, MI 48824

sly@msu.edu

Works Cited

Beach, David. 1993. “Schubert’s Experiments with Sonata Form: Formal-Tonal Design versus Underlying Structure.” Music Theory Spectrum 15: 1–18.

Cohn, Richard. 1999. “As Wonderful as Star Clusters: Instruments for Gazing at Tonality in Schubert.” 19th-Century Music 22: 213–32.

Kopp, David. 2002. Chromatic Transformations in Nineteenth-Century Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Piston, Walter. 1948. Harmony. Revised ed. New York: Norton.

Sly, Gordon. 2001. “Schubert’s Innovations in Sonata Form: Compositional Logic and Structural Interpretation.” Journal of Music Theory 45: 119–50.

—————. 2009. “Design and Structure in Schubert’s Sonata Forms: An Evolution Toward Integration.” In Keys to the Drama: Nine Perspectives on Sonata Forms, ed. Gordon Sly, 29–55. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Taruskin, Richard. 2005. The Oxford History of Western Music. Vol. 3: The Nineteenth Century. New York: Oxford University Press.

Footnotes

1. The bullet in Damschroder’s notation indicates a missing root (as in Piston 1948).

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2012 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Carmel Raz, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits: