Directional Tonality in Schumann’s Early Works *

Benjamin K. Wadsworth

KEYWORDS: Schumann, monotonality, directional tonality, tonal pairing, double tonic complex, topic, expressive genre

ABSTRACT: Beginning and ending a work in the same key, thereby suggesting a hierarchical structure, is a hallmark of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century practice. Occasionally, however, early nineteenth-century works begin and end in different, but equally plausible keys (directional tonality), thereby associating two or more keys in decentralized complexes. Franz Schubert’s works are sometimes interpreted as central to this practice, especially those that extend third relationships to larger, often chromatic cycles. Robert Schumann’s early directional-tonal works, however, have received less analytical scrutiny. In them, pairings are instead diatonic between two keys, which usually relate as relative major and minor, thereby allowing Schumann to both oppose and link dichotomous emotional states. These diatonic pairings tend to be vulnerable to monotonal influences, with the play between dual-tonal (equally structural) and monotonal contexts central to the compositional discourse. In this article, I adapt Schenkerian theory (especially the modifications of Deborah Stein and Harald Krebs) to directional-tonal structures, enumerate different blendings of monotonal and directional-tonal states, and demonstrate structural play in both single- and multiple-movement contexts.

Copyright © 2012 Society for Music Theory

[1] In the “high tonal” style of 1700–1900, most works begin and end in the same key (“monotonality”), thereby suggesting a hierarchy of chords and tones directed towards that tonic.(1) This hierarchical approach also explains to a lesser extent works having a tonally ambiguous beginning.(2) Occasionally, however, works will begin and end in different, but unambiguous keys (“directional tonality”), thereby associating keys in decentralized complexes, and even suggesting their approximate equality (“dual tonality”).(3) In early nineteenth-century music, Schubert’s eclectic approach to mediant relationships, particularly chromatic ones, is often taken as representative of the tonal innovations of that time.(4) For instance, Schubert’s “Der Alpenjäger” features segments of two chromatic third cycles that depict a youth’s desire to head off on a hunt, his leaving for the hunt, and the spirit of the mountain intervening to protect the intended quarry. The beginnings of sections (measures 1, 26, and 55) articulate a major-third cycle of C,

[2] Robert Schumann’s early period (1830–1839) also features a small number of directional-tonal works. Although the non-harmonic aspects of his music have been closely studied, most notably musical form and metrical dissonance, his approach to directional tonality is curiously unexplored.(6) This is a shame, since Schumann’s directional-tonal techniques provide a window into some of his most extreme and compelling expressive moments. In contrast with Schubert’s frequently chromatic motions between structural tonics, Schumann’s global motions are much more restrictive: they are (1) entirely diatonic since Schumann always follows chromatic regions with material in the beginning tonic;(7) (2) always related by consonant intervals, since dissonant intervals (seconds, tritones) are unstylistic; (3) third-related since motions by perfect fifth resolve to one key;(8) and (4) much more commonly related by minor third (relative major/minor) instead of by major third.(9) Thus, Schumann’s normative directional-tonal motions (and the structural pairings resulting from them) are by diatonic minor third, whereas major-third motions can be viewed as exceptions. (Sometimes apparent directional-tonal situations arise through local displacements of tonic chords, but these cases are easily viewed as monotonal.)(10) All diatonic pairings closely relate their tonics since their scales preserve many common tones, leaving them vulnerable to monotonal reinterpretation.(11) Diatonic minor-third pairings, preserving all the tones of one scale, are simply extreme cases of this phenomenon. Such pairings are not marked by virtue of the tonal relation, but they may be marked if they are combined with surface discontinuities.

Example 1. Marked modulation from D minor to F major in Schumann‘s Intermezzo op. 4, no. 5

(click to enlarge)

[3] Example 1 shows a passage from Schumann’s op. 4, no. 5, an especially interesting (and unusual) directional-tonal work that moves from F major to D minor.(12) This passage reverses the course of the entire work by going from a clear D minor tonality in measures 29–32 to a cadence in C (second ending), which is reinterpreted as V of F major by measure 44. The modulation from D minor to F major, at first glance, is seamless. It is marked, however, due to the registral ascent in measures 32–35, the hemiola pattern in the outer voices, and the parallelism of

[4] Schumann’s directional-tonal works based on relative keys create the effect of two opposing mental states (or dramatic agents) within one person’s mind, as suggested by contrasting major and minor modes. The most extreme dual-tonal states I have found are in emotionally charged works (e.g., the “Florestan” movement from op. 9 Carnaval), nightmarish intrusions into pastoral scenes (op. 4, no. 5), and humorous, scherzo-like works (op. 21, no. 3). While we cannot map the dual-tonal/monotonal opposition directly onto Schumann’s own mental dichotomy of “Florestan” and “Eusebius,” directional tonality is nonetheless advantageous as one way of expressing his “Florestan” side.(13) Similarly, the dual-tonal/monotonal opposition resonates with the literary modes of Jean Paul Richter, perhaps Schumann’s most consistently favored novelist.(14)

[5] This study enumerates dual-tonal structures that emerge from relative major/minor relationships, suggests a hypothetical continuum that blends dual-tonal and monotonal extremes, and applies this method to analyses of both short movements and longer, multi-movement contexts. For my structural models, I build on Schenkerian methods as extended by Deborah Stein (1985) and Harald Krebs (1980, 1981, 1996), since relative keys fit so comfortably within a monotonal perspective. Throughout, I show the expressive effects of directional-tonal structures using the semiotic approach of Robert Hatten (1994, 2004).

I. Directional-tonal Structures Arising from Diatonic, Minor-Third Pairings

[6] Analyzing the interaction of monotonal and directional-tonal contexts requires first formulating those contexts on their own. “Monotonal” works are unproblematic: they typically begin and end in the same key.(15) From a Schenkerian perspective, they have a single Ursatz in one key, or a fragment of it.(16) In terms of their expression, monotonal works tend to assimilate problematic keys and their associated topics to one overall tonic and its topical state (“expressive genre”), particularly if the work begins and ends in the same mode and with similar thematic material.(17)

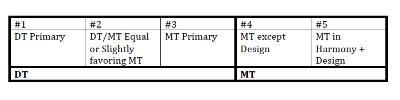

Example 2. Continuum of directional-tonal states between sectional/continuous extremes

(click to enlarge)

[7] Directional-tonal works, which begin and end in equally clear (but different) keys, present greater challenges to an adapted Schenkerian method. Example 2 shows different formal situations, ranging from sectional to continuous, that lead to different narratives and structures. An “abrupt” directional-tonal work (#1) has a sudden modulation between two keys and an equally sudden contrast between their thematic material, thereby suggesting an expressive contrast between opposed mental states, ideas, or characters (since the contrasting states interact little). An “overlapped” directional-tonal work (#3) instead has a slower structural modulation created by frequent alternations between two keys and a thematically continuous texture. Since the two keys interact and undermine each other, these works feature a rivalry between keys, each of which functions in some ways as a dramatic agent. Shown in the middle row are “hybrid” directional-tonal works (#2), which have the quick thematic changes of the abrupt works but the harmonic alternations of the overlapped ones. Hybrid narratives can be interpreted as abrupt or overlapped, with an added possibility of changing topics between restatements of the same key (i.e., topical transformation).

Example 3. Instances of Directional-Tonal and

Tonal-Pairing Structures

a. Directional-Tonal

(click to enlarge)

b. Tonal-Pairing

(click to enlarge)

[8] Example 3 shows harmonic structures resulting from the formal situations of Example 2, focused here on

[9] The structures shown in Example 3 assert a looser sort of unity than does Schenker’s Ursatz. Instead of showing a coherent motion within one key, they depict a shift of emphasis within the same diatonic collection, recalling somewhat the mixture of tonal and modal frameworks seen in the “bifocal tonality” of Jan La Rue (2001, 292); they also map onto the “Humor/Witz” distinction of Jean Paul Richter (1973) by offering a mix of patterns and contrasts. All directional-tonal states between relative keys change expressive genre midstream, mapping onto a minor/major or “tragic/non-tragic” distinction (Hatten 1994, 67–90).

[10] The “overlapped” works (and, to a lesser extent, the “hybrid” ones) may be analyzed harmonically by either the structural common tone from Example 3a (if we wish to view their rivalry on a local level) or by two simultaneous graphs from Example 3b (tonal pairing), one in each of the paired keys (if we wish to view their rivalry in terms of the complete work). As seen in Example 3b, one graph usually has an open beginning, the other an open ending, thereby asserting the priority of both keys instead of only one.

II. Directional Tonality and Monotonality in Schumann: An Overview

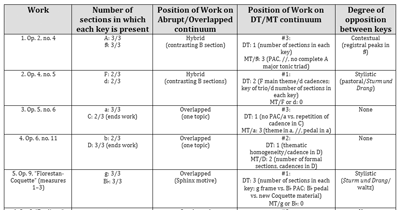

Example 4. Continuum of dual tonality (DT) and monotonality (MT)

(click to enlarge)

[11] Having enumerated possible structures within the environment of relative major and minor, we next analyze how Schumann’s early music blends monotonality and directional tonality. Example 4 shows a continuum from dual tonality (equal structural status of two keys) to monotonality (one overall key): this continuum yields narratives having either two successive expressive genres or one primary one. The association of any work with the continuum’s dual-tonal (left) end is due to two keys having advantages and disadvantages that cancel each other out, whether exactly or approximately;(22) in works on the monotonal (right) end, one key has advantages that the other lacks.(23) Although the exact advantages/disadvantages are particular to a given work, four common ones concern (1) the stability of tonic triads, (2) the markedness of the dissonances resolving to each tonic, (3) the normativity of harmonic progressions and form, and (4) the cumulative duration of each tonic (which often results in differences in formal weight).(24) In Example 4, the distinction between directional tonality and monotonality is either/or, as shown in the bottom row. The top row, however, contains gradations within the dual-tonal and monotonal perspectives: directional-tonal contexts can be stacked in favor of dual tonality (#1), equally stacked or slightly favoring monotonality (#2), or favoring monotonality (#3); in monotonal contexts, the work’s thematic and textural elements can either highlight contrasts between keys (#4), or affirm the overall key through a normative arch form (#5). Characteristically, Schumann exploits all of the gradations represented in Example 4 in his early works from 1830–39 (i.e., opp. 1–23, 26).(25) As shown in Example 5, his directional-tonal works make special use of gradations #1–3.

[12] Example 5 examines Schumann’s early works (represented by his piano works opp. 1–23 and 26) for instances of the three categories of directional-tonal works from Example 2. Works with abrupt shifts are shown in 5a; works with hybrid and overlapped states are shown in 5b.(26) To be included within either table, works must meet some minimum thresholds: they must (1) begin and end in different keys; (2) have an equal number of formal sections in each of the paired keys; and (3) assert the initial key of the pairing for the duration of at least one phrase (typically four bars in length for Schumann). In cases that violate criteria #2 and #3 (e.g., by having more formal sections in one key than its competitor), other criteria must compensate. Works shown in Example 5 must also be individual movements, not multi-movement units or sections of movements.(27)

Example 5. Schumann‘s directional-tonal works in

opp. 1–23 and 26

a. “Abrupt” directional-tonal works

(click to enlarge)

b. “Hybrid” and “Overlapped” directional-tonal works

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[13] In Example 5a, a total of four works from this period may be considered to be abruptly directional-tonal, as each asserts a sudden textural and motivic contrast with little tonal overlap between its tonal areas. From left to right, Example 5 shows the work, the paired keys and their interval of relation, the position of each work on the dual-tonal/monotonal continuum, and the reasons particular to each work that put it in this category. As seen in the second column, two of these four works pair minor-third related keys; the other two pair major-third related keys. The third column shows that three of these works are in category #2 (competing dual-tonal and monotonal perspectives) from Example 4.

[14] Similarly, Example 5b lists the hybrid and overlapped directional-tonal works, of which there are eleven total. Reading from left to right, the second column measures the cumulative duration of each key by counting the number of global formal sections in which it occurs; the third column identifies whether works are hybrid or overlapped; the fourth situates each work on the dual-tonal/monotonal continuum from Example 4; and the fifth shows the degree of topical opposition between paired keys. The degree of opposition shown in the fifth column is classified into three gradations: keys may be unsupported by contextual or topical contrasts (“none”), supported by “contextual” contrasts (e.g., register), or supported by topical (i.e., “stylistic”) contrasts.

[15] Example 5b suggests some interesting properties of Schumann’s directional-tonal works. The second column shows that most works have all formal sections in both keys, and that all of them pair diatonic keys a minor third apart. (The sheer number of overlapped works that pair relative keys (eleven) indicates that the two major-third, abrupt cases shown in Example 5a are exceptions.) In cases with a less prevalent key, that key usually ends the work, thereby balancing the structural strength of the paired tonics and indicating dual tonality. The third column of Example 5b shows five hybrid works and six overlapped ones. The fourth shows four instances of #1 pairings (see especially the nightmarish deformations of pastoral works in op. 4, no. 5 and op. 15, no. 11), two of #2 pairings, and five of #3 pairings. As shown in the fourth column, there is a loose tendency for works on the dual-tonal end to have stronger (i.e., topical) oppositions between keys, while works closer to the monotonal pole have much weaker (contextual or no) oppositions. As seen in both Examples 5a and 5b, Schumann’s directional-tonal works are structurally and expressively diverse.

III. Examples of Different Monotonal and Directional-Tonal Blendings

[16] Since the degree of blending between different structures (monotonal and dual-tonal, abrupt and overlapped) is of special interpretive interest, this section analyzes three different directional-tonal works, starting at the dual-tonal extreme and working towards the monotonal one. In all cases, the relationship between structural viewpoints maps onto a relationship between expressive genres.

Analysis 1: Dual-tonal perspective primary (#1) in op. 9, “Florestan” and measures 1–3 of “Coquette’

Example 6. Analysis of a #1 blending:

“Florestan” from op. 9 (Carnaval)

a. Problematic end of “Florestan” movement

(click to enlarge)

b. Fragile monotonal structure in G minor

(click to enlarge)

c. Directional-tonal move from G minor to major (tonal pairing view)

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

d. Topical events at the surface of “Florestan”

(click to enlarge)

[17] The “Florestan” movement represents one of the most extreme dual-tonal states in Schumann’s early oeuvre. Its expressive intensity, representative of Schumann’s passionate side, features quick modulations between G minor and ![]()

![]()

[18] Example 6d shows various interactions in the same work between Sturm und Drang and waltz topics (both associated with the G/

[19] By the end of the B section the static

Analysis 2: Directional tonality, one key slightly prior in op. 2, no. 7 (#2)

[20] This work’s abrupt directional-tonal move from F minor to

Example 7. Analysis of a #2 blending (op. 2, no. 7)

a. Directional-tonal reading from F minor to

(click to enlarge)

b. Monotonal view in

(click to enlarge)

c. Surface events in op. 2, no. 7

(click to enlarge)

[21] As shown in Example 7, dual-tonal and monotonal perspectives are equally balanced (#2 from Example 4). Example 7a shows a directional-tonal reading: a sudden modulation (measures 8–9) from F to

[22] The monotonal

[23] Extending our view of op. 2, no. 7 to the surface (Example 7c) reveals an adapted “tragic-transcendent” narrative between the two sections, each of which can be read as portraying a different character (or different aspects of the same).(30) In measures 1–2, the first section associates the minor mode with a “folk” style as supported by the drone bass of F3, higher, non-normative registers in the right hand melody, and “tragic” markers such as

Analysis 3: Tonal pairing and directional tonality in “Aveu” from Carnaval, a monotonal perspective strongly favored (#3)

Example 8. An analysis of a #3 blending: “Aveu,” op. 9 (Carnaval)

a. F-minor graph of tonal pairing

(click to enlarge)

b.

(click to enlarge)

c. Directional-tonal view of “Aveu”

(click to enlarge)

d. Topical events at surface

(click to enlarge)

[24] Example 8 analyzes the deceptively simple “Aveu” from Schumann’s op. 9 Carnaval. In light of its directional tonality, multiple alternations between F minor and

[25] The tragic (“plaintive”) aspects of “Aveu” are primary, as shown in Example 8d, so that its close on

[26] The end of “Aveu” is most interesting in terms of expressive genre: a failure of the tragic (plaintive) genre, thereby bringing needed relief, but without any effort from

Expressive Conclusions

[27] The three analyses of directional-tonal motions at the minor third, as seen in Examples 6–8, raise questions of expressive purpose. Although impossible to answer with certainty, a stylistic perspective suggests a rationale for Schumann’s alternatives to monotonality. In my view, the directional-tonal techniques and their expressive genres provided Schumann with tools to depict a wide variety of opposed mental states, with the minor-third interval best unifying the contrast within one persona. This heuristic was likely inspired by Jean Paul’s oppositions between different characters (or sides of the same character), which affirmed his own fluctuations in mood and energy (Daverio 1997, 37–39) and inspired his composition of works having analogues to such fluctuations, as seen in this article. Second, Schubert’s discursive modulations by third intrigued Schumann for their psychological complexity (Daverio 2002, 47–49). And third, the early character pieces and Schumann’s sonata forms treat minor-third relationships somewhat differently. Modulations by third in the former almost always include just two tonics, whereas minor-third relationships in monotonal sonata movements are extended to complete cycles, as occurs in op. 11/I (as analyzed by Rosen [1980, 452]). In the latter, their manipulation evidences a drive towards motivic economy and unification.(34)

IV. Directional Tonality as “Problem” within Cyclic Works

[28] In general, I find that the most compelling directional-tonal states in Schumann occur in longer cyclic works. In such multi-movement contexts, individual movements are often weakly closed off from their neighbors.(35) If successions of movements preserve common thematic elements, a circular alternation of monotonal and directional-tonal contexts across movement boundaries may result.(36) In such cases, a greater fund of topical oppositions reinforces tonal contrasts between relative major and minor than would be available in a single movement. These topical changes can reinterpret recurrences of the same key, thereby suggesting personal metamorphosis. In this way, a monotonal/dual-tonal approach gets to the heart of Schumann’s early aesthetics, especially in his op. 2 Papillons (“Butterflies”) and the later cycles (e.g., opp. 6 and 9) that grew from its inspiration.

Example 9. Dual-tonal/monotonal play in “Coquette” and “Replique” (op. 9)

a. “Coquette‘Replique:” directional-tonal structure

(click to enlarge)

b. Surface events in “Replique”

(click to enlarge)

c. “Florestan‘Replique:” a problematic, large monotonal structure in G minor

(click to enlarge)

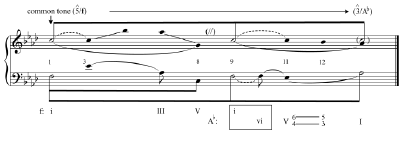

[29] Example 9 traces intra-movement and multi-movement structures in two linked movements from op. 9 that follow (and comment upon) “Florestan”: “Coquette” and “Replique.” My focus is on the play between monotonal contexts in G minor and directional-tonal shifts between G minor and

[30] Recall that the close of “Florestan” and the first three bars of “Coquette” directly compose out the dramatic conflict between

[31] In response to the problem, “Coquette” redefines the waltz topic associated with

[32] Example 9a shows a multi-movement, directional-tonal analysis of “Coquette” and “Replique,” which is supported by their common use of material from “Coquette.” “Coquette” is in ![]()

![]()

[33] G minor at the close of “Replique” reinterprets the G tonic of “Florestan,” which was associated with vivid topical contrasts, as disappointed and topically unopposed. Example 9b, which examines selected surface events from “Replique,” shows how “Replique” provides commentary on both “Coquette” and—to a lesser extent—“Florestan.” It has a contemplative texture typical of the “Eusebius” side of Schumann’s persona. Melodic lines in soprano and tenor ranges are related by imitation (see arrows), thereby suggesting dialogue; a direct quotation of measures 1–3 from “Coquette” recalls its events as well. As seen at the end of Example 9b, the final cadence of “Replique” is on a G minor tonic that is weakly prepared with a bass delay (arrow) and a haphazard, leaping approach to from instead of from the more typical . Perhaps the previously stable

[34] Building upon the previous analyses, could one posit all three movements as one monotonal unit in G minor, and one tragic expressive genre? Example 9c pursues this line of inquiry. A primary tone of D5 is sustained until its descent to G in “Replique”; it is supported by a <V–i> harmonic motion and a bass arpeggiation of the G minor tonic triad. Since Example 9c is normative as a Schenkerian reading, it should be admitted as one valid structural option within the temporal process of the three movements. It has the advantage of showing a long-range connection between vivid and muted topical contrasts, a technique that resonates with the “Witz” of Richter and Schlegel. This three-movement grouping, however, lacks thematic consistency between the first and third movement: it becomes even more tenuous if we add “Papillons,” as Smith (2009, 50) has proposed, due to its new thematic material (even though “Papillons” is in

V. Final Considerations

[35] Schumann’s early directional-tonal situations, while similar at times to directional-tonal situations in works by other composers, are as a whole unusual within a nineteenth-century context: his pairings are always diatonic; they are generally by minor third; and they involve only two third-related keys. By contrast, Schubert’s directional-tonal works pair a variety of diatonic and chromatic keys, sometimes moving in larger cycles of major or minor thirds. Although Schumann’s pairings are conservative in origin, their aesthetic treatment is highly experimental, giving rise to dual-tonal states, circular oscillations between dual-tonal and monotonal states, topical metamorphoses, and a variety of collisions between tragic and non-tragic expressive genres.

[36] Schumann’s distinctive handling of directional-tonal techniques cautions us against viewing nineteenth-century music as an age of unmitigated progress towards chromatic tonality, free “atonality,” and other styles that are often assigned a high aesthetic value. Although monotonality is a norm in early nineteenth-century works, and chromatic tonal cycles (especially major thirds) are distinctive, these trends are not binding on all composers. Conservative and diatonic in basis, Schumann’s directional-tonal states nonetheless give rise to some of his most daring tonal experiments. In our study of Schumann’s early music, overarching stylistic narratives are valuable in modeling generic expectations; his style, however, also has personal characteristics that differ from other composers of his era. An awareness of both generic and personal contexts, as well as analytical methods sensitive to them, will surely enrich our analytical practice.

Benjamin K. Wadsworth

Kennesaw State University

1000 Chastain Road, MU 119

Kennesaw, GA 30144

bwadswo2@kennesaw.edu

Works Cited

Agawu, Kofi. 1994. “Ambiguity in Tonal Music: A Preliminary Study.” In Theory, Analysis, and Meaning in Music. Edited by Anthony Pople, 86–107. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Anson-Cartwright, Mark. 2001. “Chasing Rainbows: Wolf’s “Phänomen” and Ideas of Coherence.” Journal of Music Theory 45, no. 2: 233–61.

Bailey, Robert. 1985. “An Analytical Study of the Sketches and Drafts.” In Wagner: Prelude and ‘Transfiguration’ from “Tristan und Isolde,” 113–46. New York: Norton.

BaileyShea, Matthew. 2007. “Hexatonic and the Double Tonic: Wolf’s ‘Christmas Rose.’” Journal of Music Theory 51, no. 2: 187–210.

Bribitzer-Stull, Matthew. 2006a. “The

—————. 2006b. “The End of Die Feen and Wagner’s Beginnings: Multiple Approaches to an Early Example of Double-Tonic Complex and Associative Theme.” Music Analysis 25, no. 3: 315–40.

Burstein, L. Poundie. 2005. “Unraveling Schenker’s Concept of the Auxiliary Cadence.” Music Theory Spectrum 27, no. 2: 159–86.

Daverio, John. 1989. “Schumann’s ‘Im Legendton’ and Friedrich Schlegel’s ‘Arabeske.’” 19th-Century Music 11, no. 2: 150–63.

—————. 1990. “Reading Schumann by Way of Jean Paul and His Contemporaries.” College Music Symposium 30, no. 2: 28–45.

—————. 1993. Nineteenth-Century Music and the German Romantic Ideology. New York: Schirmer.

—————. 1997. Robert Schumann: Herald of a New Age. New York: Oxford University Press.

—————. 2002. Crossing Paths: Schubert, Schumann, and Brahms. New York: Oxford University Press.

Ferris, David. 2000. Schumann’s Eichendorf “Liederkreis” and the Genre of the Romantic Cycle. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hatten, Robert. 1994. Musical Meaning in Beethoven: Markedness, Correlation, and Interpretation. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

—————. 2004. Interpreting Musical Gestures, Topics, Tropes: Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Hoeckner, Berthold. 1997. “Schumann and Romantic Distance.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 50, no. 1: 55–132.

Kaminsky, Peter. 1989. “Principles of Formal Structure in Schumann’s Early Piano Cycles.” Music Theory Spectrum 11, no. 2: 207–25.

Komar, Arthur. 1971. “The Music of Dichterliebe: The Whole and its Parts.” In “Dichterliebe”: An Authoritative Score. Edited by Arthur Komar, 63–94. New York: Norton.

Kopp, David. 2002. Chromatic Transformations in Nineteenth-Century Music. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Krebs, Harald. 1980. “Third Relation and Dominant in Late 18th- and Early 19th- Century Music.” PhD diss., Yale University.

—————. 1981. “Alternatives to Monotonality in Early Nineteenth-Century Music.” Journal of Music Theory 25, no. 1: 1–16.

—————. 1991. “Tonal and Formal Dualism in Chopin’s Scherzo, Op. 31.” Music Theory Spectrum 13, no. 1: 48–60.

—————. 1996. “Some Early Examples of Tonal Pairing: Schubert’s ‘Der Wanderer’ and ‘Meeres Stille.’” In The Second Practice of 19th-Century Tonality. Edited by William Kinderman and Harald Krebs, 17–33. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

—————. 1997. “Schumann’s Metrical Revisions.” Music Theory Spectrum 19, no. 1: 35–54.

—————. 1999. Fantasy Pieces: Metrical Dissonance in the Music of Robert Schumann. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

La Rue, Jan. [1957] 2001. “Bifocal Tonality: An Explanation for Ambiguous Baroque Cadences.” The Journal of Musicology 18 no. 2: 283–94.

Lester, Joel. 1995. “Robert Schumann and Sonata Forms.” 19th-Century Music 18, no. 3: 189–210.

Lewis, Christopher. 1987. “Mirrors and Metaphors: Reflections on Schoenberg and Nineteenth-Century Tonality.” 19th-Century Music 11, no. 1: 26–42.

Marston, Nicholas. 1993. “‘Im Legendton’: Schumann’s ‘Unsung Voice’.” 19th-Century Music 16, no. 3: 227–41.

Martin, Nathan John. 2010. “Schumann’s Fragment.” Indiana Theory Review 28: 85–109.

Neumeyer, David. 1982. “Organic Structure and the Song Cycle: Another Look at Schumann’s Dichterliebe.” Music Theory Spectrum 4: 92–105.

Perrey, Beate Julia. 2002. Schumann’s “Dichterliebe” and Early Romantic Poetics: Fragmentation of Desire. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Richter, Jean Paul. 1973. The Horn of Oberon: Jean Paul Richter’s School of Aesthetics. Translated by Margaret Hale. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Roesner, Linda. 1991. “Schumann’s ‘Parallel’ Forms.” 19th-Century Music 14, no. 3: 265–78.

Rosen, Charles. 1980. Sonata Forms. New York: Norton.

—————. 1995. The Romantic Generation. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Schenker, Heinrich. 1979. Free Composition. Translated by Ernst Oster. New York: Longman.

Schlegel, Friedrich. 1958—. Kritische Friedrich Schlegel Ausgabe. Edited by Ernst Behler, Jean-Jacques Anstett, and Hans Esichner. 35 vols. Munich, Paderborn, Vienna: Schöningh.

Schoenberg, Arnold. [1954] 1969. Structural Functions of Harmony. Edited by Leonard Stein. New York: Norton.

Smith, Peter. 2006. “You Reap What You Sow: Some Instances of Rhythmic and Harmonic Ambiguity in Brahms.” Music Theory Spectrum 28, no. 1: 57–97.

—————. 2009. “Harmonies Heard from Afar: Tonal Pairing, Formal Design, and Cyclical Integration in Schumann’s A-minor Violin Sonata.” Theory and Practice 34: 47–86.

Stein, Deborah. 1985. Hugo Wolf’s Lieder and Extensions of Tonality. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press.

Footnotes

* I would like to thank Kelly Francis, Dave Headlam, Mark Richards, Peter Franck, Harald Krebs, and the anonymous readers of Music Theory Online for their helpful feedback on earlier drafts of this article.

Return to text

1. Although Schoenberg (1969, 19) is closely associated with the notion of “monotonality,” this essay views a monotonal work in Schenkerian terms (as asserting one Ursatz).

Return to text

2. For discussions of auxiliary cadences, the typical Schenkerian explanation of off-tonic beginnings, see Schenker (1979, 87–88 and Figure 110) and Burstein (2005, 160–61).

Return to text

3. For more on directional tonality, see Krebs 1980 and 1981 and Stein 1985; with regard to “dual tonality,” see the equivalent “double tonality” in Stein 1985, 7; for the related concept of “double-tonic complex” (a complex of keys creating foreground harmonic anomalies), see Bailey 1985, Lewis 1987, Anson-Cartwright 2001, Bribitzer-Stull 2007a, and BaileyShea 2007.

Return to text

4. Krebs 1980, 1981, and Krebs 1996, Kopp 2002, and Bribitzer-Stull 2006a focus on Schubert and Chopin, not Schumann.

Return to text

5. For a directional-tonal analysis of the song, see Krebs 1981, 3–6.

Return to text

6. Form: Rosen 1980, Newcomb 1987, Roesner 1991, Lester 1995, and Martin 2010; resonance of early Romantic thought: Marston 1993, Hoeckner 1997, Daverio 1989, 1993, 1997, and 2002, and Perrey 2002; metrical dissonance: Krebs 1997, 1999. A study combining issues of resonance with harmonic structural concerns is Ferris 2000, who maintains a largely monotonal perspective.

Return to text

7. A modulation to the Neapolitan, from G minor to

Return to text

8. An instance of a perfect-fifth pairing: op. 2, no. 2 begins with an introduction in ![]()

Return to text

9. In Schumann’s early works, there are only two instances of major-third directional-tonal works: op. 6, no. 16, which modulates from a G major scherzo to a B minor trio; and op. 21, no. 8, which modulates from

Return to text

10. In op. 15, no. 12 the expected cadential goal of the work (E minor) is substituted for by a related chord (A minor), but otherwise implied by context; likewise, in op. 16, no. 5 the harmonic close of a movement (D major or V) overlaps with the next movement (G minor or i), thereby asserting a <V–i> cadence across the movement boundary.

Return to text

11. Some authors collapse pairings of relative majors/minors into monotonal states. Rosen (1995, 47–48) considers relative major/minor pairings as prolonging a single, expanded key, similar to the “double-tonic complex” of Bailey 1985. More selectively, Krebs (1981, 3) claims that pairings with a common Kopfton (e.g., relative major/minor) resolve to the more prevalent key due to the high degree of similarity between the tonics. Both arguments, I believe, are overstated. Rosen seems to argue that one can perceive two tonics at the same time, when their perception would seem to require shifts of attention; Krebs, on the other hand, conflates the similarity between different key areas with distinctions in their structural status, phenomena that are independent in many musical styles.

Return to text

12. For a general discussion, see Daverio 1997, 91–92; for an analysis of metrical conflict, see Krebs 1999, 196–97); Daverio (1993, 51) notes the highly dissonant close of the work’s alternativo section.

Return to text

13. For a vivid discussion of the expressive effects of the “Florestan” movement from Schumann’s op. 9, see Rosen 1995, 98–100..

Return to text

14. Daverio (1990, 38–45; 1993, 64–75) shows a close relationship between tonal dualities and the aesthetic of fragmentation that underlies Jean Paul Richter’s notion of Humor (incompatible viewpoints expressed by pairs of characters); likewise, he finds an analogue to Richter and Schlegel’s notions of Witz (subtle connections that occur to a composer or are teased out by a reader) in motivic variations. See Richter 1973, 71–103 and 120–47 and Schlegel 1958, vol. 2, pg. 158.

Return to text

15. Less frequently, “off-tonic beginnings” assert what appears to be the overall key, but that key lasts only for a short duration, usually not even for a complete phrase. A second key instead underlies the majority of the work. For instance, Beethoven’s fourth Piano Concerto op. 58, third movement appears to begin in C, but its opening turns out to be IV of G by the end of the movement’s first phrase (measures 1–10).

Return to text

16. For instances of tonally open works, see the discussion of one-part forms in Schenker 1979, 131 (Examples 6–7).

Return to text

17. Expressive genres are introduced in Hatten 1994, 67–90.

Return to text

18. Stein (1985, 145–46) proposes a similar approach, the retention of the same Kopfton (although my approach allows for an added prolongation of in one of the two keys). Elsewhere, however, Stein (1985, page 146) adopts an approach that is unsuited to the highly fused relative major/minor relationship: disjunct Kopftöne that are the same scale degree in their respective keys.

Return to text

19. Agawu (1994, 89) observes that a hierarchical approach (such as Schenkerian theory) will as a matter of course resolve competing interpretations in favor of the preferred one. As noted by Smith (2006, 59), however, some patterns (such as the prolonged soprano note) are sufficiently indeterminate so as to suggest a multiplicity of contexts throughout a work’s course. There is thus room for dual-tonal analyses within an expanded Schenkerian theoretical framework.

Return to text

20. Krebs (1996) notes the ability for tones in the soprano to “pivot” harmonically between paired keys. His analysis on page 21 of Schubert’s “Der Wanderer” preserves all soprano events (except for the hypothetical ending in

Return to text

21. Directional-tonal, common-tone structures let the duality of two tonics stand, just as Richter’s notion of Humor posits incompatible viewpoints expressed by pairs of characters; likewise, common-tone correspondences between paired keys in either of Example 3’s structures suggest subtle connections to be teased out by a listener, just as instances of Witz may be ferreted out by an astute reader. See Richter 1973, 71–103 and 120–47 for further discussions of the two concepts.

Return to text

22. A caveat: dual-tonal states, by claiming the equal structural priority of their two tonics, may slightly misrepresent to different readers the stability of different techniques, e.g., cadences and pedal points. Note, however, that analyses of structural priority are always approximate; in my own analytical experience, for instance, I have yet to encounter a Schenkerian analysis that asserts one structural key on the basis of a “51/49” split.

Return to text

23. For a similar way to gauge the structural priority of two tonics, see Anson-Cartwright 2001, 241.

Return to text

24. Schenker instead tends to view the durations of key centers as irrelevant to the more global structural levels (e.g., Schenker 1979, 15).

Return to text

25. Unsurprisingly, category #5 is seen most commonly in works from this period; #4 occurs occasionally, for instance in Schumann’s op. 2, no. 2.

Return to text

26. It is important to keep in mind that directional-tonal movements comprise a subset (only) of Schumann’s dual-tonal works, some of which assert tonal pairings within monotonal frames, others asserting decentralized complexes without stating tonics literally.

Return to text

27. The lists become unmanageable when portions of movements and multi-movement units are considered.

Return to text

28. I have selected a Kopfton of D for two reasons: (1)

Return to text

29. Similarly, Daverio (1990, 39) shows dialectical interactions between the waltz topic and various learned styles (e.g., canon) in Schumann’s op. 6.

Return to text

30. Daverio (1997, 84) notes that Schumann at one time described the movement as inspired by Jean Paul’s Flegeljahre: an entreaty by Vult that his brother consent to an exchange of costumes. This interpretation, however, is weakly confirmed by the movement’s topical content (at best).

Return to text

31. A variety of topics are troped: a waltz-like meter (3/8) is undercut by a relatively slow tempo, a textural undercurrent of a duet in octaves in the top staff, and by a generic “singing style” that exists as a default in character-piece genres such as the nocturne and prelude.

Return to text

32. A dominant divider in F minor (measure 8) is a structural indication that F minor controls measures 1–8. Since

Return to text

33. Interestingly, “Aveu” is positioned at the end of a series of movements (starting with “Chopin”) that pair

Return to text

34. An increased comfort with tonal cycles within the character pieces becomes evident only from the late 1830s in works such as the Novelletten, no. 1 (1838), which modulates between F,

Return to text

35. Ferris (2000, 106–9) calls weakly closed movements “open endings” when their cadences are weakened through rhythm, formal placement, and so on; similarly, he defines “weak openings” (121–23) as defining their starting tonics ambiguously.

Return to text

36. It is important not to overstate the unifying effect of structures linking movements. Arthur Komar (1971, 80) and Peter Kaminsky (1989, 210–16) propose bass-line analyses of Dichterliebe (op. 48) and Carnaval (op. 9) that assert prolongations of single tonic triads. In general, as noted by Ferris (2000), these overstate the referential status of their tonics: in Kaminsky’s analysis of op. 9, for instance, many interior movements are related directly to the initial (and ending)

Return to text

37. Daverio (1993, 50–51) points out that some listeners may be unable to distinguish these movements’ boundaries without access to a score; Smith (2009, 48–51) discusses the circular effects of tonal motions between G minor and

Return to text

38. In addition to Example 9, a two-movement tonal structure occurs in the first two songs from the op. 48 Dichterliebe, the first of which begins and ends on V7 of

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2012 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by John Reef, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits: