Songs for Hands: Analyzing Interactions of Sign Language and Music

Anabel Maler

KEYWORDS: American Sign Language, popular music, multimedia, gesture, Deaf culture, music and disability

ABSTRACT: Song signing has long played an important role in Deaf cultures around the world. Recently, sign-language song translations have crossed over from the Deaf to the hearing world; entire communities of Deaf, hearing, and hard-of-hearing song signers now flourish on YouTube. The resulting videos form multimedia events featuring music, English, American Sign Language (ASL), gestures, pantomime, and even costumes.

Artistic song signing presents music analysts with a unique challenge. This paper asks how sign language, gestures, sung words, and music interact to shape our understanding of a given song. Using Stephen Torrence’s video interpretation of the song “Fireflies” by Owl City and other supporting examples, I show how the song signer can represent musical features by altering existing signs or creating new ones. More specifically, I reveal how Torrence represents pitch, timbre, and phrasing through sign alteration and manipulation of the signing space. Additional examples demonstrate multiple methods for articulating phrases in signed songs. The analysis draws on scholarship from ASL literary research, popular music analysis, and studies of music and gesture.

Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory

PART I: Introduction to Song Signing(1)

[1.1] “Song signing” is a traditional form of storytelling found in Deaf cultures around the world.(2) The act of song signing involves translating a pre-existing song’s lyrics into a signed language, or composing an original sign language song. The signed song is one of many face-to-face storytelling traditions in Deaf culture (Bahan 2006). Recently, song signing has been popularized through videos on YouTube. Consequently, the signed song has crossed over into the hearing world, and YouTube has become an online haven for communities of Deaf, hearing, and hard-of-hearing song-signers. In the present paper, I approach the signed song through a music-analytical lens. I ask how the signed interpretation conforms to the sounding music, how the performer alters signs and manipulates the signing space in order to convey musical features, and how the signer’s movements can influence our understanding of the music’s meaning and form. I first provide a brief introduction to the signed song and its role in Deaf and hearing cultures. Next, I identify some important aspects of American Sign Language (ASL) and ASL poetry, which will aid in understanding how signs are manipulated in song-signing performances. Finally, I provide an analysis of Stephen Torrence’s interpretation of the Owl City song “Fireflies,” along with additional supporting examples.(3)

[1.2] Music scholars may be surprised to learn about the existence of signed songs and the appreciation and creation of music by members of the Deaf community. Deaf people almost always retain some degree of hearing and they are certainly not insensitive to the consequences of sound. In addition to sound, the tactile, the visual, and the kinesthetic all play important roles in deaf perceptions of music (Straus 2011, 169). More broadly, these other modes of perception have been shown to be significant beyond the Deaf and hard-of-hearing community, since musical experience in general involves sensory input from multiple sources.(4)

[1.3] Song-signing performances comprise four principal forms of expression: music, lyrics, the signs of ASL, and other gestures independent of the signed language (i.e. dancing, swaying, pulsing, etc.). Like English, ASL is a natural symbolic language with its own distinct set of grammatical rules; it can thus be learned and understood like any other language. In contrast to aural language, however, the visual and kinesthetic nature of signed language also links it to analogic forms of expression, such as music and dance.(5) Just as singing is bounded by language, the signs in ASL songs can be seen as providing “material grounding that can help constrain the slippery acoustic bounds of musical forms” (Bickford 2007, 440). Conversely, musical features equally constrain linguistic content in both singing and song signing. The analysis of sign language songs affords an opportunity to explore how the four different modes of expression involved in these songs relate to one another, and thus to understand the contributions they make to musical expression within the signed song.

PART 2: Song Signing in Deaf Culture

[2.1] Music has long played an important role in Deaf cultures around the world. In fact, one of the earliest records of song signing can be found in a film project by the National Association of the Deaf, produced between 1910 and 1920 (Bahan 2006, 23). Bahan observes that there are two traditional types of signed songs in Deaf culture: translated songs, and percussion signing (2006, 34). The “translated song” is a genre in which “the lyrics of various songs are translated into ASL and performed for an audience” (34). Bahan gives the example of the song “Yankee Doodle” as a commonly translated song from the early- to mid-twentieth century. Percussion signing involves “arranging signs to certain beats” (34). A famous example is the “Bison Song,” a traditional sports song written in the 1960s by Dorothy Miles.(6)

[2.2] ASL song interpretations are also commonly found in churches and are variously performed by hired interpreters, students of sign language, and entire choirs of amateur and experienced signers (hearing and deaf). Another major form of song signing exists in the classroom. Language programs for all signing levels often incorporate a musical component. Many of the song-signing videos on YouTube consist of classroom performances by beginner and intermediate sign language students.

[2.3] In the present paper, I am most concerned with artistic song signing, a genre of ASL song that falls into Bahan’s category of “translated songs.” Often, these songs go beyond mere translation to become what Cook (1998) terms “instances of multimedia,” combining music and sign language with costumes and special effects. Artistic song signing can be found both in live performances and in YouTube videos, performed by individuals with a variety of hearing abilities. These song signing videos and performances are usually based on popular songs rather than on art music.(7)

[2.4] The signed songs found on YouTube have been the subjects of some controversy within Deaf culture. On the forum AllDeaf, questions about song signing have garnered mixed responses, ranging from condemning “boring” renditions by people who want to “show off a partial skill at anything” to praising signed songs as “awesome” and “beautiful.” Many contributors to the forum expressed their discomfort with situations like the one described here: “a young girl ‘knows some sign language.’ So for church or whatever she decides to get up and sign a song (rather than [singing] it). She’s hearing. The audience is hearing. Everyone cried because it was ‘so beautiful and expressive’” (AllDeaf Forum 2012). The preceding quotation suggests that critique of song signing may be due to its increasing popularity within hearing culture and the appropriation by hearing performers of a Deaf art form.(8) In spite of this controversy, evidence of song signing’s continued popularity can be found in both Deaf and hearing cultures following the establishment of D-PAN, the Deaf Professional Arts Network, and a recent increase in media interest in song signing.(9)

[2.5] Signed songs are performed in a variety of situations by individuals with widely varying hearing abilities for a diverse and, in the case of YouTube videos, largely anonymous audience. It can therefore be difficult to place song signing within a single cultural context. Signed songs can be found throughout the continuum defined by Jessica Berson in her work on performing deaf identity (2005, 43); that is, some signed songs lie on the “inside” end of the continuum, meaning that they are produced by Deaf artists for Deaf audiences, others are “outside” performances produced for both hearing and Deaf audiences, and still others lie somewhere in the middle.(10) Stephen Torrence, whose videos I analyze in Parts 3 and 4 of this paper, produces signed songs near the “outside” end of Berson’s performance spectrum. Torrence (known on YouTube as CaptainValor) is a hearing person who has studied ASL at both high school and post-secondary levels. He creates song-signing videos for recreational and artistic purposes. Torrence has stated in an interview that his goal is “to make [his videos] accessible to both deaf and hearing” (Wilson 2009). While it is true that the majority of his audience is also hearing, Torrence’s videos do reach a wide range of people, from those with no knowledge of sign language to fluent and native signers.(11) Although many song signers, like Torrence, are hearing and do not identify as belonging to Deaf culture, others identify as Deaf, hard of hearing, or Children of Deaf Adults (CODAs). Four famous examples are Signmark, Sean Forbes, Rosa Lee Timm, and TL Forsberg.(12)

[2.6] I have chosen to analyze Torrence’s videos for several reasons. First, Torrence provides captions containing the English lyrics and corresponding ASL interpretation, called a gloss, for all of his song-signing videos (Vicars 2012). Secondly, Torrence prioritizes the musical aspects of song signing. In personal correspondence, I asked Torrence how prominently the sounding music figures into his interpretations. He responded that he weights “the musical ‘feel’ of [his] interpretation much higher than other song signers.” Due to musical considerations, he has “often had to sacrifice ASL grammatical accuracy for musicality.” By choosing to analyze Torrence’s videos, I do not mean to suggest that they are representative of the longstanding tradition of song signing that exists within Deaf culture. Rather, his work provides an excellent example of the kind of song signing that has become popular on YouTube: the signed song as an artistic outlet for anyone, deaf or hearing.

PART 3: Analyzing Signed Songs

[3.1] Conducting an analysis of signed songs requires knowledge of a few key elements of ASL and signed poetry. Before embarking on a complete analysis of a song interpretation, I will discuss two aspects of sign language that are important for understanding signed poetry and songs: the construction of signs and sign alteration.

I. Constructing Signs

Example 1. “Take it easy”

(click to watch video)

[3.2] Each sign in a sign language is composed of three basic parameters: handshape, location, and movement (Kaneko 2011). One or more handshapes must be present in a sign. Signs may be located on the body or off it, to one side or the other, in the so-called “neutral space” in front of the body, or outside of the neutral space. The other, less well-defined features of a sign are the orientation of the hand and non-manual cues (facial expressions). Facial expressions are especially crucial to understanding signed languages. In Example 1, I show the sign TAKE-IT-EASY, which includes a specific facial expression. In different sign languages, facial expressions can play different roles. In Israeli Sign Language, for instance, facial expressions are more strictly grammatical in function than in ASL. In any sign language, the importance of facial expressions for comprehension should not be underestimated.

[3.3] Handshapes are often repeated to create the visual equivalent of rhyming in sign language poetry (Kaneko 2011). Other parameters of the sign (for example, movement or non-manual expression) may also be repeated or manipulated in the creation of rhymes or other poetic techniques (Kaneko 2011; Sutton-Spence, Ladd, and Rudd 2005; Valli 1990). A signer will sign more with one hand than the other: this is called the dominant hand, and it is usually correlated with left- and right-handedness.

Example 2. Manual alphabet

(click to watch video)

[3.4] Many of the handshapes used in ASL can be found in the ASL manual alphabet, which provides one handshape for each letter of the English alphabet. The ASL alphabet is one-handed, unlike the British Sign Language (BSL) alphabet, for example, which requires the use of both hands to form letters. Readers unfamiliar with the basic handshapes of the manual alphabet and numbering system may wish to view the demonstration of the ASL manual alphabet and number signs in Example 2.(13)

[3.5] Non-linguistic gestures, or gesticulations, also play an important role in sign language, although the prevalence in signed languages of manual gestures like the ones that accompany verbal languages has been the subject of some debate. David McNeill has argued that since the “kinesic-visual medium is grammatical and socially regulated for the deaf,” signs cannot reflect the same early, imagistic stage of thought exhibited in speech-accompanying gestures (1993, 156). Karen Emmorey has since shown in her exploration of the topic that “signers do gesture, but not in the same way that speakers do” (1999, 155). Instead of providing the spontaneous hand gestures that accompany verbal language, signers produce facial and body gestures simultaneously with signing, and these gestures fulfill some of the same communicative and cognitive functions of manual gestures (Emmorey 1999, 154-55). Signers also produce “manual gestures that alternate with signing,” which are often iconic or metaphoric (155).(14) All of these sign-accompanying gestures are also employed by song signers in order to communicate aspects of the music to the viewer.

II. Altering Signs

Example 3. Torrence‘s interpretation of “I‘ve Got a Feeling” by the Black Eyed Peas

(click to watch video)

Example 4. “Party”

(click to watch video)

Example 5. “Start”

(click to watch video)

Example 6. “Go out and smash it” and “let‘s kick it off” productive signs

(click to watch video)

Example 7. Miley Cyrus, “Party in the USA”

(click to watch video)

[3.6] In poetic as well as song signing, signs can be manipulated and altered. Artistic signers often use neologisms, or newly coined words, for creative purposes. In sign language, these are called productive signs. To create a productive sign, the signer can either modify an existing sign or produce a totally new sign out of the basic elements of sign language (Johnston and Schembri 2007; Sutton-Spence, Ladd, and Rudd 2005, 70). While productive signs are also used in everyday signing, they play an especially important role in sign language poetry and songs.

[3.7] Torrence’s interpretation of “I’ve Got a Feeling” in Example 3 features several productive signs due to his emphasis on rhythm and his use of gestures familiar from hip-hop, such as record scratching, chopping motions, loose handshapes, and regular, rhythmic pulsation of the body.(15) I wish to point out two signs in particular from this clip. First, the sign PARTY occurs with the lyrics “Go out and smash it.” Second, the sign START accompanies the lyrics “let’s kick it off.” These are evidently accurate translations of idiomatic English expressions. The movements in Torrence’s video, however, do not correspond exactly to the regular versions of the ASL signs PARTY and START (Examples 4 and 5). Torrence signs PARTY up high, outside of the normative signing space of the sign PARTY, with a forceful rhythmic motion in order to match a single sign to a full English expression in terms of both rhythm and meaning. The same thing happens when the single sign START is matched to the expression “let’s kick it off,” where START is modified by jerking the dominant signing hand towards the signer in an added movement representing the word “off,” imitating the separation in the song between “let’s kick it” and “off” with two distinct gestures (Example 6). These are productive signs derived from pre-existing signs. The component signs are modified from their original forms, however, not only for expressive reasons, but also for musical (rhythmic) reasons. Ordinary productive signs are found in everyday signing and are typical of signed poetry, but the productive signs used by song signers are unique in that they rely on the presence—be it heard, felt, or assumed—of music. For the deaf viewer, the knowledge that there is music playing and that Torrence’s movements seem deliberate and dance-like is sufficient for understanding that there is a degree of conformance between the music and the signer’s gestures. Thus, I term these signs “productive musical signs,” since they represent one or more musical features through sign. This term encompasses both the production of an entirely new sign out of the fundamental elements of a signed language and the modification of an existing sign for musical reasons.

[3.8] Rhythm is probably the most immediately recognizable musical feature used in altering signs. Pitch, timbre, and phrasing, however, also find expression in a song signer’s manual and non-manual gestures. The following paragraphs describe song signers’ methods for communicating phrasing through ASL.

[3.9] I have observed four methods for conveying phrase units in signed songs; these can be identified as lyric, rhythmic, pulse, and melodic methods. Robin Attas describes lyric closure in song as occurring “with the end of a grammatical clause, phrase, or sentence; or with the use of a word that is important in the overall rhyme scheme” (2011, 6). In the case of song signing, lyric closure simply involves the use of an ASL poetic device such as handshape rhyming in order to signal the completion of a phrase. Signers can create rhythmic closure by resting or holding a sign after performing several in quick succession. Torrence’s interpretation of Miley Cyrus’s song “Party in the USA” provides an excellent example of this technique (Example 7).(16) At the beginning of the first verse, Cyrus sings “I hopped off the plane at LAX with my dream and a cardigan. Welcome to the land of fame excess, am I gonna fit in?” Torrence glosses these lyrics as “PLANE EXIT [LAX] HAVE DREAM AND COAT. THIS PLACE FAMOUS, EXCESSIVE, PEOPLE ACCEPT ME?” After signing the first words in a flurry of movement, Torrence holds the sign COAT for two beats to show that the phrase has ended. Similarly, he holds the sign ME for a full beat at the end of the next phrase. Since I or ME is one of the simplest and most common signs in ASL, simply involving pointing at one’s chest, it is generally signed quickly. Combined with Torrence’s emphatic knee-bend and facial expression, this suggests that Torrence’s elongation of the sign ME is quite deliberate.

[3.10] The “pulsing” method of phrase delimitation is closely related to rhythmic closure. Pulsing is one of the most common and noticeable ways of defining a phrase in ASL songs, and consists simply of the regular pulsation of the signer’s body in time with the beat while either holding or repeating a full sign or part of one. This movement is clearly linked to dancing, but in terming it “pulsing” I emphasize its separation from pure dance. These movements always occur in conjunction with a sign or part of a sign, and are used at the ends of phrases in order to signal the attainment of a goal. In between the phrases and formal units of signed songs, pure dance often does appear without being accompanied by any parameters of a sign. These dance moments do not fall into the category of “pulsing”; rather, they indicate to the viewer that there has been a break in the song’s linguistic content, after which the song will continue. For examples of the pulsing technique, see [4.5] and [4.9] below.

Example 8. Kelly Clarkson, “Already Gone”

(click to watch video)

Figure 1. Kelly Clarkson, “Already Gone”

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

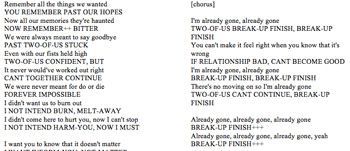

[3.11] Finally, Attas (2011) points to arch-shaped melodies, which can promote a sense of departure and return, as a source of goal-directed motion. Song signers can also define phrase goals using melodic techniques. Although the signer’s movements are of course silent, I have chosen to mirror Attas’s terminology in this case since the word “melodic” provides a useful metaphor for the arc-shaped motions used by song signers in demarcating phrases. When I refer to this type of melodic phrasing, I mean the directed motion of a signer’s body throughout a phrase. This motion is often directed from one side of the body to the other, from low to high, or vice versa. Torrence provides an example of melodic directed motion in his interpretation of Kelly Clarkson’s “Already Gone” (Example 8).(17) The lyrics and gloss for “Already Gone” can be found in Figure 1. In the first verse, Torrence signs YOU REMEMBER PAST OUR HOPES, NOW REMEMBER BITTER to correspond to Clarkson’s phrase, “Remember all the things we wanted / Now all our memories they’re haunted.” As he signs these words, Torrence turns his body first to his right on the sign HOPES, and then to his left on the signs NOW REMEMBER BITTER. The third line, “we were always meant to say goodbye,” is separate from the first two, and is signed from the center of the body. The movement between right, left, and middle indicates the location of the sign within the phrase (beginning, middle, or end). Torrence’s motion from side to side is thus a gestural rather than a grammatical use of the signing space. That is, the repeated movement is not required for the correct formation of the signs. As Susan Goldin-Meadow has noted, “the signer’s use of space conveys a great deal of information” (2003, 204). From the perspective developed in Goldin-Meadow’s work, Torrence’s gestural use of the signing space could reveal his subconscious attention to the parts of the phrase. For these reasons, Torrence’s consistent use of the same locations to represent different parts of a phrase is quite significant.

Example 9. “Hopes” and “bitter”

(click to watch video)

[3.12] Torrence’s movements between the right, left, and middle of the signing space in “Already Gone” represent not only parts of the phrase, but also stages of the protagonist’s relationship in the song. Torrence signs towards his right to represent positive memories, towards his left to represent unfortunate present circumstances, and towards the centre when reflecting on the situation. In his interpretation of the phrase “now all our memories, they’re haunted” as NOW REMEMBER BITTER, Torrence modifies the sign BITTER with an extra outward motion towards the viewer, so that the non-dominant hand starts with the same bent B handshape that forms the sign HOPES (Example 9). As Torrence turns from right to left, the sign HOPES transforms into BITTER. As this example shows, a musical technique used by the song signer to define a phrase can also act as a means of expressing the song’s textual meaning.(18) Torrence uses sign location in order to express meaning in “Already Gone” by physically representing the transformation of the protagonist’s positive memories into negative ones. And since storytelling in sign language also uses shifts in the signing space to represent different characters and locations, signers are attuned to the importance of location for understanding a story.

PART 4: Analysis of “Fireflies”

Figure 2. “Fireflies” rhyme scheme, first verse and chorus

(click to enlarge)

Figure 3. Owl City, “Fireflies”

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Example 10. Owl City, “Fireflies”

(click to watch video)

[4.1] In this section, I provide an analysis of Stephen Torrence’s signed interpretation of the Owl City song “Fireflies.”(19) In the course of the analysis, I identify three musical features that are represented by Torrence through ASL: pitch, timbre, and phrasing. The song itself consists of an instrumental introduction followed by a simple verse-chorus form with three strophes.(20) Each verse consists of two parts, labeled a and b in Figure 2. The colored words in the chart represent the rhyme schemes of the lyrics and the signs. Torrence’s full gloss of “Fireflies” is reproduced in Figure 3. I begin by exploring the song’s introduction and verses before analyzing the chorus.

[4.2] Torrence establishes a conformance of music and sign in the synthesizer introduction to “Fireflies” (Example 10). He attaches a specific B handshape to a purely instrumental passage and correlates the movement of the dominant hand to the contour of the melody, bringing in the non-dominant hand to imitate the entrance of bells. Torrence thus establishes a conformance of music and sign using handshapes that represent purely musical features. The height of the B-hand in this case corresponds roughly to the frequency of the synthesized pitches, in the sense that we understand pitch in terms of “high” and “low.”

[4.3] It would be difficult for many deaf viewers to hear the melodic content of the synthesizer introduction, since higher sounds are generally less accessible to the profoundly deaf than low sounds. Torrence thus increases the intelligibility of his movements at the beginning of “Fireflies” through the creation of a new, purely musical sign. Isolated as it is here, the B handshape carries no particular meaning (although it is part of the ASL sign SONG). He gives the gesture meaning by meeting all of the requirements of a sign: it has a handshape (B), it moves back and forth and up and down, it is located in the neutral space and above the signer’s head, and the orientation of the hand shifts, the palm facing alternately forward and back. By blending musical and sign inputs, Torrence creates a productive musical sign, one which is not based on a pre-existing sign but exists purely for the purpose of expressing the pitch, rhythm, texture, and introductory function of the synthesizer introduction.(21) With the creation of this productive sign, Torrence bypasses the necessity of hearing the relationship between high and low: he maps the metaphor into the spatial domain, making it intelligible regardless of hearing ability.

Example 11. Rhyming techniques in “Fireflies”

(click to watch video)

[4.4] Rhyming techniques feature prominently in Torrence’s interpretation of first verse. Please refer to Example 11 and to the still shots extracted from Torrence’s videos in examples 12 through 16. The still shots in these examples are meant as aid for analyzing rhyming signs. Watch Torrence’s handshapes and facial expressions on the following rhymes in the first verse: “eyes” and “fireflies”; “open air,” “everywhere” and “stare”; “believe” and “slowly”; and “asleep” and “seems.” Torrence uses a combination of manual and non-manual rhyming techniques to mirror the rhymes in the song’s lyrics (as discussed in 3.3). The rhyme between the signs AMAZING and LIGHT-UP is self-evident—the open B handshape remains consistent between the signs, as do the widened eyes (Examples 12 and 13). Torrence’s eyebrows, which were raised with the sign AMAZING, come down on the sign LIGHT-UP. This motion corresponds with the rhyme between “eyes” and “fireflies” in the lyrics (Figure 2). The rhyme between SEE and FLIES is perhaps more subtle, but the similar sharpness of the V handshape of SEE and the G handshape of FLIES is heightened by both gestures moving outwards from the signer’s body (Examples 14 and 15).(22) In the b section of the verse, the manual rhymes consist mainly of G and V handshapes, starting close to the body and moving outwards, pointing toward the viewer. These handshapes occur in the dominant hand on the signs FLIES NUMEROUS and in both hands on the signs TEARS ALL-AROUND (Example 16). Interestingly, the verse ends on the emphasized sign LOOK-AROUND, with Torrence’s eyes wide and eyebrows raised, creating a larger structural demarcation for the first verse, with a facial rhyme between AMAZING and LOOK-AROUND marking the boundaries of the verse (Examples 12 and 17).

|

Example 12. “Amazing” (click to enlarge) Example 14. “See” (click to enlarge) |

Example 13. “Light-up” (click to enlarge) Example 15. “Flies” (click to enlarge) |

|

Example 16. “Tears all-around” (click to enlarge) |

Example 17. “Stare” (click to enlarge) |

Example 18. Gestural crescendo

(click to watch video)

Example 19. Backing vocal line in “Fireflies”

(click to watch video)

[4.5] Torrence’s interpretation of the second verse highlights the “pulsing” technique. As discussed in [3.10], the “pulsing” technique blends linguistically meaningful signs or sign components with dance to indicate a phrase’s completion. In this case, Torrence pulses on the sign DANCE at the end of the first phrase, and on the final sign of the verse, the productive sign HANG THIN LINE. The pulsation on the sign DANCE is typical, remaining constant for several beats before the start of the next phrase. The second instance of pulsation features a gradual opening in the use of the signing space, from a small LINE at face height, to the upper and lower limits of the normal signing space, and finally exploding outside of the signing space at the beginning of the chorus. This gestural crescendo mimics the audible crescendo in the percussion and the explosive entrance into the full string sound that marks the beginning of the chorus (Example 18).

[4.6] Song signers can also communicate musical ideas by using manual gestures and manipulating the signing space. In the third verse of “Fireflies,” for example, a backing vocal line appears and presents the song signer with some additional interpretive challenges (Example 19). The vocal line interjects the words, “please take me away from here” three times in the a section of the verse (see Figure 3 above). Torrence’s treatment of the added voice is interesting in that he does not attempt to sign the backing vocal’s lyrics. Instead, he represents the added voice with a manual gesture. Furthermore, he associates the other voice with rhythm by strongly correlating his movements first with the signs themselves during the lead vocal line and subsequently making his movements much more rhythmic, without signs, when the backing voice enters. He also uses the signing space more freely in this section, associating the lower area of the space with the lead vocals and the higher area with the backing vocal. Torrence uses the signing space in this way in order to represent the different timbres of the lead and backing vocals. Young’s backing voice is slightly thinner and is accompanied by more of the higher, brighter instruments in the mix, like the piano and bells. Torrence’s use of a higher signing space is especially appropriate for representing this lighter timbre.

Example 20. Manual and non-manual rhyming, rhythm, and pulsing

(click to watch video)

[4.7] Three song-signing techniques feature prominently in the chorus: manual and non-manual rhyming, rhythm, and pulsing (Example 20). The chorus consists of the following lyrics: “I’d like to make myself believe that planet Earth turns slowly. It’s hard to say that I’d rather stay awake when I’m asleep, ’cause everything is never as it seems.” Torrence signs BELIEVE and SLOW when Young sings the corresponding lyrics, creating a handshape rhyme (Example 21 and 22). Both signs involve two 5 handshapes with fingers closed, coming together in front of the signer’s body. Whereas in everyday conversation, a signer would more typically slow down WORLD TURN to represent the Earth revolving slowly, Torrence deliberately adds the sign SLOW to create this distinctive handshape rhyme. In the chorus’s second phrase, Torrence interprets the lyrics “It’s hard to say that I’d rather stay awake when I’m asleep, ’cause everything is never as it seems” as I PREFER SLEEP, DREAM, NOT AWAKE. WHY? VARIETY. This gloss results in the odd juxtaposition of the sign SLEEP with the word “awake” and the sign AWAKE with the word “sleep.” The phrase “’cause everything is never as it seems” is also interpreted rather distinctively as WHY? VARIETY. The handshape rhyme between AWAKE (L handshape) and VARIETY (G handshape) may explain Torrence’s odd choice of signs (Examples 23 and 24). The inner world of sleeping and dreaming versus wakefulness, represented by signs near the face or with the face turned away from the viewer, transforms into the world that the protagonist sees around him, characterized by the G handshape placed away from the signer’s body and moving in a circle in the sign VARIETY. Important non-manual cues are also present in the chorus. Namely, Torrence’s face stays relaxed through the first rhyming couplet, but in the chorus’s second half, his face becomes animated, his eyebrows raised, and his eyes widened. This matches the popular conception of B and 5 handshapes as symbolically more open and positive than pointed handshapes, and shows that Torrence considers the music in terms of formal sections. Whereas the first verse consisted mostly of pointed handshapes, the openness of the B and 5 handshapes creates a dramatic contrast that visually sets the chorus apart from the verse.

|

Example 21. “Believe” (click to enlarge) Example 23. “Awake” (click to enlarge) |

Example 22. “Slow” (click to enlarge) Example 24. “Variety” (click to enlarge) |

[4.8] In general, as in the case of “Fireflies,” rhythmic gestures are often the most salient factor in differentiating a song’s chorus and verses. In many cases, the chorus is more rhythmically consistent and driven than the verse. This is akin to the notion of a chorus’s “catchiness,” expressed in the rhythm of the signer’s body rather than the heard melody. In the chorus, signers tend to pulse their bodies on every beat, using forceful, confident motions. Such contrasting gestures are quite typical of signed choruses.(23) Exceptions to this trend can be found in some slow ASL songs.(24) In general, though, choruses in signed songs feature some type of rhythmic separation from the verses.

Figure 4. Metric placements

(click to enlarge)

[4.9] Torrence defines the chorus’s internal phrasing using the pulsing method. Figure 4 shows the metric placement of each word and each sign of the chorus.(25) In the first line of the chorus, Torrence holds the sign BELIEVE, which falls halfway through the phrase, almost as long as he holds the final sign, SLOW. Since faster movement precedes both of these signs, and since the two signs are nearly equivalent in length, there is little rhythmic differentiation of the two halves of the phrase. The phrase’s end is, however, quite clearly defined through the pulsing method: Torrence begins to sign SLOW on beat 1 of bar 4 and holds the sign through beats 2, 3, and 4 while pulsing on each beat. Torrence uses the same pulsing technique combined with a simple held sign in the second phrase of the chorus. His repetition of the sign VARIETY for the final two beats of the phrase’s third measure creates a sense of rhythmic pulsation, heightened by his nodding head. Subsequently, he holds the sign’s 1 handshapes by moving them outwards in a slow half circle throughout measure four. The pulsation technique evident in Torrence’s interpretation of “Fireflies” is one that can also be seen in many of his other signing videos, and may be one factor in the success of his interpretations.(26)

PART 5: Conclusions and Future Directions

[5.1] As should be apparent from the preceding, signed song offers much of interest to music researchers. In my analysis of “Fireflies,” I showed how song signer Stephen Torrence portrays musical elements like rhythm, pitch, phrasing, and timbre through productive musical signs and non-linguistic gestures, enriching the musical experiences of the deaf and hearing alike. Our perception of music can only be enriched through the practice of nurturing different kinds of hearing, including the kind of deaf hearing described by Straus (2011). Song signing presents us with an opportunity to expand our understanding of familiar songs and to experience them in new ways.

[5.2] The present analysis represents but one approach to signed song; other fruitful avenues for research could include an ethnographic study of song signers and their audiences, a study of song signing in the classroom, and research into the perception of signed songs by audiences with varying hearing abilities. The field of music and gesture provides potentially the most suitable home for further research on song signing.(27) The entire analytical enterprise of this paper begs an obvious question for that field: can gestures in fact communicate musical concepts independently of sound? This problem has been taken up in recent scholarship on music and gesture. Recent publications by Michael Berry (2009) and by Rolf Inge Godøy and his colleagues (2006) address the importance and independence of musical gestures. Berry, for his part, argues that we do not “need sound to interpret the gestures that we are seeing” when we observe the movement of musicians (2009, 3). To demonstrate the musical capabilities of the body, Berry analyzes Sofia Gubaidulina’s use of gesture in her silent pieces, in which she fills the musical space with “gesture instead of sound.” He proposes that Gubaidulina creates a “musical sign language” where musical gestures “suggest sound production and keep the listener focused on the performers” (2009, 23). As in Berry’s work, my own research concerns the use of non-music-producing gestures that can take the place of sound. Song signing presents a slightly different set of circumstances, however, since the song signer’s linguistic and extra-linguistic gestures take place alongside sound, complementing and supporting the sounding music.

[5.3] Rolf Inge Godøy and his colleagues Egil Haga and Alexander Refsum Jensenius (2006) address a gestural situation similar to the one found in song signing in their study of “air instrument” performance. They assert that “images of sound-producing gestures are an integral part of the perception of musical sound” and can aid in “identifying, discriminating, grouping, or doing ‘auditory scene analysis’ of musical sound, as well as remembering, recalling, and imagining musical sound” (256). The authors distinguish between sound-producing gestures, which are made “with the intention of transferring energy from the body to an instrument,” and amodal, affective, or emotive gestures, which may include movements associated with “more global sensations of the music, such as images of effort, velocity, impatience, unrest, calm, anger, etc.” (257). Godøy, Haga and Jensenius further argue that in air instrument playing, these emotive or expressive gestures tend to “fuse with sound-producing gestures.” The authors also observe the use of sound-tracing gestures in air instrument playing, where the performer traces “melodic contours, rhythmical/textural patterns or timbral/dynamical evolutions with hands, arms, torso, or whole body” (257). I would argue that song signers use non-linguistic gestures to fulfill the musical purpose of “filling the space with gesture instead of sound” (2009, 23), employing the same techniques observed in air instrument players. In the case of song signing, emotive or expressive gestures fuse not with sound-producing gestures, but with the signs themselves, and sound-tracing gestures are produced using whole signs or parts of signs.

[5.4] The topic of deaf music-making is also intimately tied to the field of disability studies, which was introduced to music scholarship quite recently through the work of Neil Lerner (2006), Alex Lubet (2011), and Joseph Straus (2011). Members of the Deaf community generally do not consider themselves disabled; rather, they belong to a cultural and linguistic minority. The fact remains, however, that many hearing people still consider deafness a disability, especially in terms of perceiving music. Song-signing performances have the ability to challenge such “hegemonic representations” that associate music exclusively with the ability to hear (Quinlan and Bates 2008, 67). Like the performances of the physically disabled dancer discussed by Quinlan and Bates, song-signing pieces “make accessible alternative performances of self” (2008, 67). The scholarly community is just now beginning to recognize the unique challenge Deaf music poses, and music researchers are starting to consider how deaf people hear, feel, and see music. The final chapter of Straus’s latest book addresses prodigious, normal, and disablist hearing, and includes a small discussion of “deaf hearing.” Although Straus focuses mainly on how the deaf perceive music through visual, tactile, and internal means, he also acknowledges the importance of deaf music-making (2011, 169 n42). Indeed, I would even suggest that Deaf music provides analysts with a unique opportunity to investigate how people of all different hearing abilities perceive and interact with music in order to interpret and create it with their hands and bodies. As I mentioned in the introduction to this paper, the analogical aspects of sign language and gesture correlate particularly well with the analogical resources of music, while the more symbolic aspects of sign language help us parse meaning with greater ease than if the signer’s movements were purely dance. This special property of song signing presents an opening for further analysis in the fields of disability studies, musical embodiment, and music perception.

[5.5] Finally, the signed song is an art form that combines important products of two cultures that have traditionally remained quite separate and often at odds in North America. Their intersection in song signing provides us with an invaluable opportunity to build stronger connections between hearing and Deaf artistic communities and to showcase multiple ways of hearing. As I suggested in my overview of song signing in Deaf culture, however, the relationship between the hearing and deaf in the world of signed songs is not without its complexities and problems. For example, some critical viewers on the AllDeaf forum are concerned by the abundance of hearing amateurs appropriating the language and traditions of Deaf culture. Consequently, it will be important to prioritize the work of Deaf song signers in future research on signed songs. I chose Torrence’s work because he provides such clear examples of song-signing techniques and has made his glosses public. He is, however, a hearing performer, and research into song signing cannot be complete without analyzing the work of Deaf and hard-of-hearing artists. Although the political nature of song signing is still the subject of considerable controversy, many Deaf and hearing performers continue to see the value in creating song-signing videos and shows. Ultimately, song signing has achieved a surprising degree of popularity on the Internet, revealing the genre’s immense potential for artistic expression, social change, and music research.

Anabel Maler

University of Chicago

1010 E. 59th Street

Chicago, IL 60637

amaler@uchicago.edu

Works Cited

Adams, Kyle. 2009. “On the Metrical Techniques of Flow in Rap Music.” Music Theory Online 15, no. 5.

Alfonsi, Sharyn. 2011. “Person of the Week: Ally ASL Brings Music to Deaf Followers.” ABC News, January 21. Accessed January 6, 2012. http://abcnews.go.com/Health/youtube-sensation-allyson-townsend-brings-music-deaf/story?id=12731166

AllDeaf Forum. “Your Opinion about Signing Songs?” Accessed January 6, 2012. http://www.alldeaf.com/deaf-musicians/59773-your-opinion-about-signing-songs.html

Ament, Aharona. 2010. “Beyond Vibrations: The Deaf Experience in Music.” Gapers Block, July 22. Accessed October 4, 2012. http://gapersblock.com/transmission/2010/07/22/beyond_vibrations_the_deaf_musical_experience/

Attas, Robin. 2011. “Sarah Setting the Terms: Defining Phrase in Popular Music.” Music Theory Online 17, no. 3.

Bahan, Ben. 2006. “Face-to-Face Tradition in the American Deaf Community: Dynamics of the Teller, the Tale, and the Audience.” In Signing the Body Poetic: Essays on American Sign Language Literature, ed. H-Dirksen L. Bauman, Jennifer L. Nelson, and Heidi M. Rose. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Berry, Michael. 2009. “The Importance of Bodily Gesture in Sofia Gubaidulina’s Music for Low Strings.” Music Theory Online 15, no. 5.

Berson, Jessica. 2005. “Performing Deaf Identity: Toward a Continuum of Deaf Performance.” In Bodies in Commotion: Disability & Performance, ed. Carrie Sandahl and Philip Auslander, 42–55. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Bickford, Tyler. 2007. “Music of Poetry and Poetry of Song: Expressivity and Grammar in Vocal Performance.” Ethnomusicology 51, no. 3.

Burns, Lori. 2005. “Meaning in a Popular Song: The Representation of Masochistic Desire in Sarah McLachlan’s ‘Ice.’” In Engaging Music: Essays in Music Analysis, ed. Deborah Stein, 136–48. New York: Oxford University Press.

Cook, Nicholas. 1998. Analysing Musical Multimedia. New York: Oxford University Press.

Covach, John. 2005. “Form in Rock Music: A Primer.” In Engaging Music: Essays in Music Analysis, ed. Deborah Stein, 65–76. New York: Oxford University Press.

Covach, John, and Graeme Boone, eds. 1997. Understanding Rock: Essays in Musical Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press.

Doll, Christopher. 2011. “Rockin’ Out: Expressive Modulation in Verse-Chorus Form.” Music Theory Online 17, no. 3.

Emmorey, Karen. 1999. “Do Signers Gesture?” In Gesture, Speech, and Sign, ed. Lynn S. Messing and Ruth Campbell, 133–59. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Godøy, Rolf Inge, and Marc Leman, ed. 2009. Music Gestures: Sound, Movement, and Meaning. New York: Routledge.

Godøy, Rolf Inge, Egil Haga, and Alexander Refsum Jensenius. 2006. “Playing ‘Air Instruments’: Mimicry of Sound-Producing Gestures by Novices and Experts.” In Gesture in Human-Computer Interaction and Simulation, 256–67. Berlin: Springer Verlag.

Goldin-Meadow, Susan. 2003. Hearing Gesture: How Our Hands Help Us Think. Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

Gritten, Anthony and Elaine King, ed. 2011. New Perspectives on Music and Gesture. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing.

—————. 2006. Music and Gesture. Aldershot: Ashgate.

Hatten, Robert S. 2004. Interpreting Musical Gestures, Topics, and Tropes: Mozart, Beethoven, Schubert. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Johnston, Trevor and Adam Schembri. 2007. Australian Sign Language: An Introduction to Sign Language Linguistics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Kaneko, Michiko. 2011. “Alliteration in Sign Language Poetry.” In Alliteration in Culture, ed. Jonathan Roper, 231–46. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

Lerner, Neil and Joseph N. Straus, ed. 2006. Sounding Off: Theorizing Disability in Music. New York: Routledge.

Liddell, Scott K. 2003. Grammar, Gesture, and Meaning in American Sign Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lubet, Alex. 2011. Music, Disability, and Society. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

McNeill, David. 1993. “The Circle from Gesture to Sign.” In Psychological Perspectives on Deafness, ed. Marc Marschark and M. Diane Clark, 153–84. Hillsdale: Erlbaum.

—————. 1992. Hand and Mind: What Gestures Reveal About Thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Mead, Andrew. 1999. “Bodily Hearing: Physiological Metaphors and Music Meaning.” Journal of Music Theory 43, no. 1: 1–19.

Moore, Allan. 1993. Rock: The Primary Text. Buckingham: Open University Press, 1993.

Nobile, Drew F. 2011. “Form and Voice Leading in Early Beatles Songs.” Music Theory Online 17, no. 3.

Quinlan, Margaret M. and Benjamin R. Bates. 2008. “Dances and Discourses of (Dis)Ability: Heather Mills’s Embodiment of Disability on Dancing with the Stars.” Text and Performance Quarterly 28, no. 1–2: 64–80.

Straus, Joseph N. 2011. Extraordinary Measures: Disability in Music. New York: Oxford University Press.

Summach, Jay. 2011. “The Structure, Genesis, and Function of the Prechorus.” Music Theory Online 17, no. 3.

Sutton-Spence, Rachel, Paddy Ladd, and Gillian Rudd. 2005. Analysing Sign Language Poetry. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Torrence, Stephen. Accessed January 6, 2012. http://www.youtube.com/user/CaptainValor

Torrence, Stephen. “Fireflies” by Owl City. Accessed January 6, 2012. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zlxPp0vAniY

Torrence, Stephen. “I’ve Gotta Feeling” by the Black Eyed Peas. Accessed January 6, 2012. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lGjS7TsODSM&

Valli, Clayton. 1990. “The Nature of a Line in ASL Poetry.” In SLR ’87: Papers from the Fourth International Symposium on Sign Language Research, ed. William Edmondson, and Fred Karlsson,171–82. Hamburg: Signum Verlag.

Vicars, William. ASL University. Accessed January 6, 2012. http://www.lifeprint.com/asl101/topics/gloss.htm

http://www.urlesque.com/2009/04/03/pop-songs-in-sign-language-videos/

Weber, Lindsey. 2009. “Pop Songs in Sign Language.” Urlesque, April 3. Accessed January 6, 2012.

http://www.urlesque.com/2009/04/03/pop-songs-in-sign-language-videos/

Wilson, Tracy V. 2009. “5 Questions for Stephen Torrence, ASL Signer and Jonathan Coulton Fan.” howstuffworks, September 1. Accessed January 6, 2012. http://blogs.howstuffworks.com/2009/09/01/5-questions-for-stephen-torrence-maker-of-jonathan-coulton-asl-videos/

Zbikowski, Lawrence M. 2011. “Musical Gesture and Musical Grammar: A Cognitive Approach.” In New Perspectives on Music and Gesture, ed. Anthony Gritten and Elaine King, 83–98. Surrey: Ashgate Publishing.

—————. 2002. Conceptualizing Music: Cognitive Structure, Theory, and Analysis. New York: Oxford University Press.

Footnotes

1. I would like to extend my gratitude to the music faculty at McGill University and at the University of Chicago for supporting my research over the past several years. Thanks especially to Nicole Biamonte and Lawrence Zbikowski for their valuable assistance during the writing and editing of this manuscript. Finally, I would like to thank the anonymous reviewers at Music Theory Online for their insights and helpful comments.

Return to text

2. My use of the words “Deaf” and “deaf” conforms to accepted norms within the Deaf community. To describe someone as Deaf means that they identify themselves as belonging to Deaf culture, while “deaf” refers simply to the medical condition of deafness. Not all deaf people identify as belonging to Deaf culture.

Return to text

3. YouTube videos are often deleted by the poster or by website administrators and are thus relatively unreliable as permanent sources. All YouTube videos cited in this paper may be subject to change or deletion.

Return to text

4. Godøy, Inge, and Haga 2009 and Berry 2009, for example, provide examples of situations in which musical performance practices and compositions privilege the gestural and visual aspects of musical perception.

Return to text

5. Lawrence Zbikowski has proposed that language and music make use of different forms of reference. Whereas language makes use of symbolic reference (in which arbitrary symbolic tokens are correlated with concepts), music makes use of analogical reference in the form of sonic analogs for dynamic processes (Zbikowski 2011, 84). Sign languages, however, can make use of both forms of reference. As Scott Liddell has observed, signs such as GIVEx→y are simultaneously analogic, symbolic, and indexic. The sign GIVEx→y has lexically fixed features (flat O handshape, arc-shaped movement), the indexic feature of pointing towards the verb’s intended object, and an iconic (that is, analogical) quality created by the hand’s flat O shape, which looks like it holds an object (2003, 356).

Return to text

6. A video of the Bison Song from can be found here: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4CVbUfuqXuk.

Return to text

7. To my knowledge, examples of untexted signed songs are quite rare. A performer attempting to sign an untexted piece of music would likely run into the same difficulties as would an English or French speaker simultaneously interpreting the same piece: a spoken or signed interpretation of untexted music will tend to lapse either into narration or into something resembling interpretive dance.

Return to text

8. Whether hearing song signers like Stephen Torrence are misusing sign language and appropriating Deaf identity is a controversial matter that requires further research and discussion. For an interesting critique of Torrence’s recent withdrawal from the world of song signing, see the following YouTube video created by MsFrizzyHair: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=28ATAzrVAcs. In the video, MsFrizzyHair argues that since Torrence became so popular for his sign language performances, he has a continued responsibility to represent the Deaf community. By leaving the world of song signing behind, she contends, Torrence has sent the message that sign language and signed songs no longer matter.

Return to text

9. Online articles about song signing in recent years include Alfonsi 2011, Ament 2010, Weber 2009, and Wilson 2009. Of these four articles, only Ament’s focuses primarily on deaf performers and audiences. Weber’s piece does include two videos by deaf artists, but the majority of footage in the article features hearing performers. Alfonsi 2011 and Wilson 2009 provide interviews with two prominent hearing song signers on YouTube, Allyson Townsend and Stephen Torrence.

Return to text

10. Berson describes the spectrum of Deaf performance as stretching from “outside” to “inside” performance. Outside performances are intended for audiences that are both hearing and Deaf, and can include interpreted productions in which hearing actors “shadow” Deaf actors. Inside performances are by Deaf artists for Deaf audiences and privilege the experience of Deaf viewers. Signed songs can be found all through that spectrum, depending on the orientation of both the signer and the audience.

Return to text

11. This information is anecdotal, gleaned from my experience reading comments on the profile pages and YouTube uploads of well-known song signers. As far as I know, no study has been made of the exact proportion of deaf to hearing audience members for ASL song videos.

Return to text

12. For examples of signed songs performed by a variety of Deaf artists, see D-PAN, the Deaf Professional Arts Network (http://www.d-pan.org/DPAN-videos.html).

Return to text

13. It is interesting to note that emotional effects are commonly associated with particular handshapes (Sutton-Spence, Ladd, and Rudd 2005; Kaneko 2011). For example, the 5 and B handshapes, being open, are symbolically perceived as more positive in connotation than closed handshapes, such as A or S. Handshapes that are bent at the knuckles, such as clawed 5 (an open 5 handshape with bent fingers) and clawed V, are associated with more tension and are harsher than other non-claw handshapes, which are more relaxed and softer. The G, V, I, and Y handshapes are normally perceived as sharp, while A and O handshapes are not. Certain handshapes are also “marked” by their rarity: for example, the X handshape is much more rarely used than the A handshape.

Return to text

14. McNeill (1992) defines metaphoric and iconic gestures, as well as beats, cohesives, and deictics. Iconic gestures are pictorial and “bear a close formal relationship to the semantic content of speech” (12). Metaphoric gestures are also pictorial, but they present an abstract idea or image (14). Beat gestures involve the movement of the hand “along with the rhythmical pulsation of speech” (15). Cohesive gestures tie together “thematically related” parts of discourse and emphasize continuity in speech (16). Finally, the deictic is a pointing gesture (18).

Return to text

15. The full video may be found at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CCZkQ_s-Bdk.

Return to text

16. The full video may be found at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QmKnQjBf8wM.

Return to text

17. The full video may be found at http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_Ns-yLOxUDI.

Return to text

18. For more in-depth discussion of how poetic meaning can be expressed through structure in popular music, see Burns 2005.

Return to text

19. http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zlxPp0vAniY

Return to text

20. Although I cannot include a more in-depth discussion of form in rock in the present article, interested readers might wish to refer to the following publications: Burns 2005, Covach and Boone 1997, Covach 2005, Doll 2011, Moore 1993, Nobile 2011, and Summach 2011.

Return to text

21. My use of the term “blending” here draws on Zbikowski’s work on conceptual blending as presented in Conceptualizing Music: Cognitive Structure, Theory, and Analysis. In Chapter 2, Zbikowski explores how conceptual domains such as music and language can be connected through cross-domain mapping. He further discusses conceptual blending, in which “elements from two correlated domains are projected into a third, giving rise to a rich set of possibilities for the imagination” (2002, 63). Signed songs present an interesting opportunity to discuss the process of mapping between music and language, since music and language are presented simultaneously in song signing.

Return to text

22. Torrence actually shortens the real sign for FLY, which normally consists of the sign for BUG followed by an outward motion. He apparently eliminates the BUG part of the sign in order to maintain the rhythm of the line.

Return to text

23. Another example is kmklined’s interpretation of the Bruno Mars song “Grenade” (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pQ1aSQwBZ24). In the videos of accomplished signers, this type of energetic motion in the chorus seems to be correlated with the catchiness of the chorus (although this is, of course, both speculative and subjective). By contrast, in the case of inexperienced signers the increase in confidence and rhythmic movement in the chorus has a “hearing” equivalent: after all, who cares if you hum and stumble your way through half of the verse’s lyrics if you bust out the chorus loud and proud?

Return to text

24. An example of a slow ASL song without much contrast between verse and chorus is tiffanythill’s rendition of Adele’s “Someone Like You” (http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2cz5QcVtoyQ).

Return to text

25. The rhythmic and metric representation in Figure 4 is similar to those used in the analysis of rap; see Adams 2009 for example.

Return to text

26. Pulsing is common among popular song signers on YouTube. It can be found in videos by captainvalor, kmklined, tiffanythill, and allyballybabe. Although use of the pulsing technique is not a precondition for success in the genre, since each song signer has a unique style, it does seem to correlate with a signer’s popularity. This may be because this pulsing often implies a close relationship with both music and dance.

Return to text

27. Music and gesture has received significant attention in recent scholarship. Some important texts on the topic include Mead (1999), Hatten (2004), Godøy and Leman (2009), Gritten and King (2011, 2006), and Zbikowski (2011).

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2013 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Hoyt Andres, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits: