“To Discourse Learnedly” and “Compose Beautifully”: Thoughts on Gioseffo Zarlino, Theory, and Practice

Keynote Address, Annual Meeting of the Society for Music Theory, Minneapolis 2011

Cristle Collins Judd

KEYWORDS: Zarlino, mode, history of music theory

Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory

The present text is a slightly modified and updated version of the keynote address I presented at the Annual Meeting of the Society for Music Theory, Minneapolis, October 29, 2011. I have maintained the somewhat informal tone of the text while adapting the presentation for a digital medium. I am grateful to the members of the program committee for the 2011 meeting who invited me to deliver the keynote address (Byron Almén, Chair, Richard Ashley, Julian Hook, Jocelyn Neal Wayne Petty, Robert Wason, and Lynne Rogers, ex‐officio) and to Scott Burnham for his generous introduction at the meeting. I am particularly grateful to the ensemble Singer Pur, and especially Marcus Schmidl and Martin Stastnik, for their collaboration on a recently released recording of Zarlino motets which made the publication of this keynote address possible (Singer Pur 2013). I would like to acknowledge a publication subvention from the Society for Music Theory, which supported the recorded examples of this address. I would also like to thank Michael Noone for his collaboration on the recording of another group of Zarlino motets (Ensemble Plus Ultra 2007). I am grateful for permission from each of these ensembles to reproduce audio excerpts from these recordings in this article and commend the full recordings to the attention of readers.

[1] A keynote address such as this faces many challenges and expectations, which include, but are not limited to: connecting to the broadly diverse audience of a plenary session of the Society for Music Theory; saying something meaningful that is at the same time memorable; provoking, perhaps; and, of course, all the while adopting a delivery that is humorous, witty, and urbane tempered by an appropriate air of humility. Heady—even intimidating—expectations that I will do my best to live up to!

[2] Before beginning in earnest, I will observe, with no little irony, that when one looks at the etymology of the word “keynote” in English, the pointer is to Charles Burney’s translation, in his General History of Music, of clavis as the “keynote” of a mode. . . . When you’re in my field of research, sometimes it seems not to matter what you are working on at a given moment, you somehow will never escape the modes! And as you’ll see, modes and modal theory will indeed make an appearance in the course of this lecture.

[3] With all that in mind, I initially considered several possible directions this keynote might take. The first might be described as the “grand theory” keynote in which I intended to wax eloquent on the metaphysical questions attending to our discipline while offering broad prognostications about where our discipline has been and where it should go. All in all it felt a bit pretentious (maybe even preposterous), given the many distinguished colleagues in the audience.

[4] I then swung to the opposite extreme, considering the autobiographical tack and reflections on how I got into the field and some of the unusual twists and turns my own career has taken, going right back to a quiz I took on the greater perfect system of Greek theory in an 8 a.m. freshman theory class in 1978, an event that must have scarred me for life since I recall it so clearly. But ultimately, that, too, seemed a bit pretentious and preposterous, but more in the “so what?” vein of why any of you should care.

[5] And then there was the potential address on the big project I continue to work on, related to a whole range of texts from classical Arabic writings about music to nineteenth century translations of theoretical texts by women, and how we might begin to include these writings in our thinking about history of theory. But that work is still far from fully baked, and I felt a certain audacity at skirting the program committee while landing on the biggest venue of the meeting without anyone having vetted my abstract.

[6] Ultimately, from those various attempts I did identify a series of threads that I think may be of interest and that I hope will spark dialogue into the future, or at least at the bar after this talk.

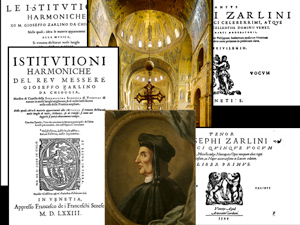

Illustration 1. Anonymous 18th-century portrait of Gioseffo Zarlino, probably copied from an engraving. (Museo internazionale e biblioteca della musica, Bologna, B 38428)

(click to enlarge)

[7] And the first disclaimer: the resulting address is somewhat autobiographical: I have spent over a decade more or less occupied by work on Gioseffo Zarlino (Illustration 1), moving in directions I never expected. And he and his work—and, as importantly, the reasons I have continued to study questions related to him—are central to this talk.

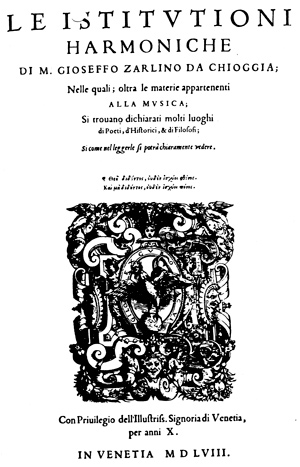

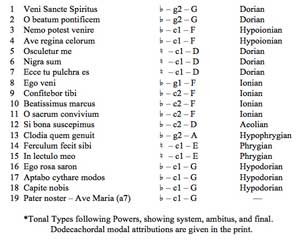

[8] In the course of this address I will share some observations that I hope may lead to a degree of reassessment of Zarlino and his work, and in so doing, I will offer some suggestions about how we approach the history of music theory and what the importance of that history is. Along the way, I would like to turn our thoughts yet again to a perhaps perennial point of discussion: the relationship of theory and practice. More specifically I will speak to the relationship of theory and composition, and yet more narrowly, how we understand that relationship as manifest in the works of a single individual. In doing so, I will take advantage of the opportunity to introduce Zarlino’s compositions, works you may be likely to know something about, but less likely to actually know or have experienced.

Illustration 2a. Photograph: Ian Bent

(click to enlarge)

Illustration 2b. Photograph: Harold Powers

(click to enlarge)

[9] Two keynote addresses that preceded mine helped to frame this talk, and I would like to acknowledge them here. They have remained of particular importance to me, perhaps because they appeared at a formative moment in my career, but also because they sounded themes mapping out a life of scholarship to which I aspired. Both were given by scholars who subsequently were generous and gracious mentors to me. So I would like to use those keynotes as a touchstone of sorts for this talk. The addresses to which I refer are Ian Bent’s 1992 keynote to the SMT, entitled “History of Music Theory: Margin or Center,” subsequently published in Theoria (Bent 1992), and Harry Powers’ keynote presented to a joint meeting of the AMS, SMT, and SEM in 1990, entitled “Three Pragmatists in Search of a Theory,” which appeared in print in Current Musicology (Powers 1993). (And it seems only fair, since I included Zarlino’s mug shot, that I should also provide portraits of Ian and Harry [Illustrations 2a and 2b].)

[10] Coincidentally, in fall 1993, near the time when both of these essays were published, I began my first year on the tenure track as an assistant professor at the University of Pennsylvania—that timing may also have helped cement these essays in my intellectual genealogy.

[11] I’d like to share an extended passage from Bent’s address:

As a subject, the history of theory is today something of an orphan. It does not quite belong in full membership of the professional world of music theory. Symptomatic of this situation is the legitimacy of a question such as the following, which a young and bright music theorist with a penchant for the historical might ask himself: “Will I damage my career prospects if I publish disproportionately in history of theory? Will I become suspect of a lack of commitment to expanding and advancing the body of contemporary compositional theory, or suspect of a disinterest in analytical practice?” (Bent 1992, 2)

He later continues:

But the same thing goes on in the field of music history. The budding historian with a penchant for the theoretical may ask herself the counter-question: “Will I damage my career prospects if I publish disproportionately in history of theory? Will I become suspect of a lack of commitment to music itself as the central concern of music history?” (Bent 1992, 3)

About both perspectives, he suggests a legitimacy to what might be perceived as paranoia underlying the question. And, although in his gender assignments, Bent may merely have been being even-handed—even attempting gender neutrality—as an aside, I am struck that the assignment of a male pronoun went to the music theorist (“a young and bright music theorist with a penchant for the historical might ask himself . . . ”) and the female to a music historian (“the budding historian with a penchant for the theoretical may ask herself . . . ”), distinctions that were representative then—as now—of real gender imbalances in the music theoretic world and its subfields.

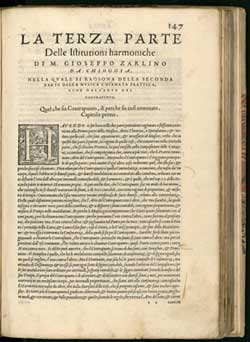

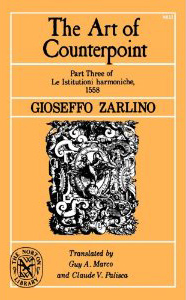

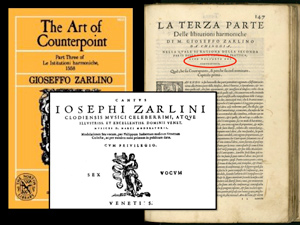

Illustration 3. Ian Bent, “History of Music Theory: Margin or Center” (1992) with annotation

(click to enlarge)

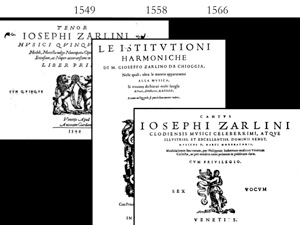

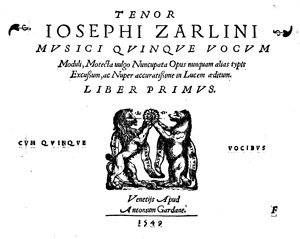

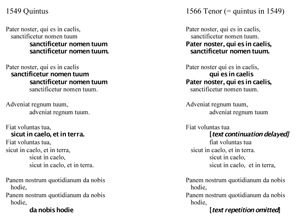

[12] Bent’s article is one that I often assigned in history of theory seminars in a class session that might loosely be described as focused on considerations of the “state of the discipline.” As I prepared this keynote, I pulled out my original copy of Theoria rather than the well-worn photocopy in my teaching files. I confess that I was stunned to see in the margins of this article—itself concerned with marginalia and marginalization—that I had scrawled beside the paragraph describing a theorist worried about career prospects—“Is this me?” (Illustration 3). I don’t think my question was about the “young and bright” part but rather about potentially damaging career prospects. Or even more to the point, my own meditations on just what sort of hybrid I was and what path that put me on. More on that in a moment . . .

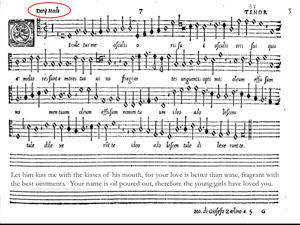

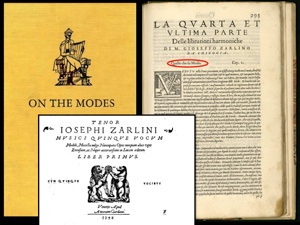

[13] I would not dare by association to claim anything like the astonishing virtuosity that attended Harry Powers’s work, but a particular statement in his keynote (Powers 1993) about where and how he placed his work continues to ring true in my own work, and that, too, I’d like to quote in extenso as background:

The distinction between the modal categories of theory and the melodic or tonal types of practice [in Indian classical music and in Gregorian chant, as in Renaissance polyphony] is not one of superordinated and subordinated levels in a single hierarchy. It is a distinction between rational idea and empirical experience, and those two need to be confronted one with the other, not just assimilated one to the other. Musical theories have cultural significance in their own right, as part of the history of ideas; music-theoretical traditions can be and should be investigated independently of practical traditions. Relationships between theory and practice are not a priori, they are ad hoc, so any eventual confrontations of theory and practice ought to be pragmatic, and on a case-by-case basis. We cannot naively adduce the writers on music in a given musical culture as straightforward testimony to musical practice. They, like we, are more likely to be handing on traditional theory, or making their own theories, rather than just objectively reporting what practical musicians are doing.” (Powers 1993, 14–15)

[14] Like almost everything Harry Powers ever wrote, this paragraph is densely packed with observations that we could spend the whole of this keynote and more unpacking it, but I want to focus in particular on this statement:

Relationships between theory and practice are not a priori, they are ad hoc, so any eventual confrontations of theory and practice ought to be pragmatic, and on a case-by-case basis.

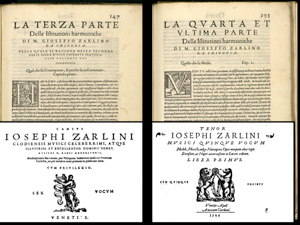

Illustration 4. Title page, Gioseffo Zarlino, Le istitutioni harmoniche (Venice: 1558)

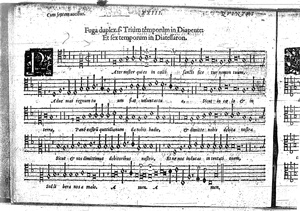

(click to enlarge)

[15] It won’t come as a surprise that the particular case I want to explore revolves around Gioseffo Zarlino. As a theorist, Zarlino’s name is well known to all in this room, although I suspect the depth of engagement with his work is considerably varied. (At this point, I am tempted to do one of those pedagogical “clicker” exercises where I throw up slides with true or false statements to find out just what the extent of knowledge is in the room before I forge ahead—but I’ll save any quizzes for the bar.) The likely point of connection for most will be his treatise, Le istitutioni harmoniche, first published in 1558 (Illustration 4). If I were a publisher bringing out a new edition of the Istitutioni harmoniche and looking for some puffs for the back of the dust jacket, I wouldn’t have a hard time finding suitable referees. Beethoven, for example, turned to Zarlino when he composed the Missa Solemnis (Kirkendale 1970). And Zarlino has certainly had reviews that many of us would covet on our book jackets. Just imagine a book cover that read like this:

no theorist since Boethius was as influential upon the course of the development of music theory – Robert Wienpahl, Journal of the American Musicological Society(1)

Zarlino alone was preeminently influential on later theorists in numerous countries. His formulations . . . were authoritative for musicians in Italy, France, Germany, and England – Joel Lester, Compositional Theory in the Eighteenth Century(2)

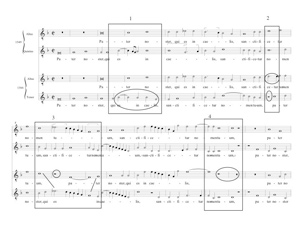

the prince of modern musicians – Rameau(3)

the theorist of his century and maybe of all centuries – Alfred Einstein(4)

I could go on to add encomia from Matthew Shirlaw, Hugo Riemann, and many, many others, but I think you get the drift.(5) I will just add one more for currency:

. . . the most famous music theorist between Aristoxenus and Rameau (Wikipedia)

[16] Notwithstanding how we as theorists might understand notions of “fame,” if Zarlino the theorist seems to have gotten stratospheric reviews, the same cannot so easily be said of Zarlino the composer, who has fared rather less well in the quantity of extravagant praise heaped upon his works. Claude Palisca, for example, described the compositions as: “learned and polished, [but] of secondary interest” (Palisca 2013). Gustave Reese, with wonderfully ambiguous, but ultimately damningly faint praise, described Zarlino as an: “estimable composer” (Reese 1954, 379). I could go on, but I think you get the drift. For consistency’s sake, I’ll again throw in Wikipedia’s opinion (which, in context, clearly owes more than a little to Palisca): “ . . . his motets are polished and display a mastery of canonic counterpoint.”

[17] My goal today is not primarily to rehabilitate Zarlino’s reputation as a composer, although I do want to explore that side of him and to understand something of the genesis of his reception as a composer. Rather, I hope to focus on that “confrontation” of theory and practice that Powers proposed and to use that as a way of making some broad claims about the “work” that theory does and the way in which it does it. However well or otherwise the Istititioni harmoniche is actually known to modern-day theorists, I suspect that many among the membership of the Society for Music Theory have at least a basic sense of the material it covers, and may have read all or part of at least book 3 and book 4 (on counterpoint and the modes) as well as encountering some of the more frequently quoted sections from the speculative books of the treatise. As for Zarlino’s compositions, I suspect it is a leap for many to have encountered anything beyond some of the counterpoint or modal duos in the treatise—I will not ask for a show of hands for those prepared to sing us a Zarlino tune.

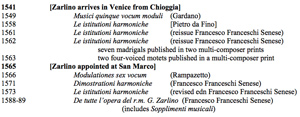

[18] Let me offer a brief timeline and quick primer of sorts on some important milestones in Zarlino’s life as a frame for the discussion which follows. Born in 1517, in Chioggia, a town on the southernmost edge of the Venetian lagoon, Zarlino was ordained as a priest and served as organist at Chioggia cathedral (where he had been a choirboy) before moving to Venice in 1541. There, in the 1540s he was a student of many things, among them Greek and Hebrew, but most notably, for our purposes, music with Adriano Willaert. What else he was doing for much of his first two decades in La Serenissima remains something of a mystery, but he did have a series of publications, including his first book of motets in 1549 and his theory treatise in 1558, which was then reissued twice in near succession (not, I would hasten to add, as a runaway bestseller, but most likely as leftover copies that were repackaged with new title pages). Several madrigals were published in 1562 and two four-voiced motets appeared in 1563. In 1565, Zarlino was appointed to the most coveted musical position in Venice when he was named maestro di cappella at the basilica of San Marco, a position he held for a quarter century until his death in 1590. Shortly after his appointment at San Marco, a second book of motets appeared, the Modulationes sex vocum, followed by six further madrigals. In 1571, he published a subsequent treatise, the Dimostrationi harmoniche, followed two years later by a substantially revised edition of the Istitutioni in 1573. Both treatises were published in revised editions in conjunction with the complete works edition appearing near the end of his life, which also included the Sopplimenti musicali. Illustration 5 summarizes these theoretical and musical publications.

Illustration 5. Timeline of selected events and publications in Zarlino’s life

(click to enlarge)

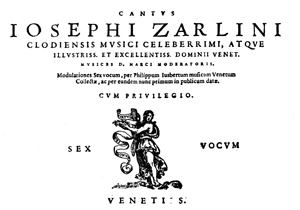

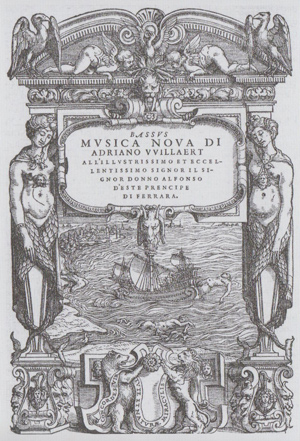

Illustration 6. Title page, Gioseffo Zarlino, Modulationes sex vocum. (Venice: 1566), Cantus partbook

(click to enlarge)

[19] The point of departure for my musings on the intersection of theory and practice (and professional career) is the publication of Zarlino’s second book of motets in 1566. This is apt, in part because I have been in the midst of an edition of these works, but also because the preface of the book provided the first part of my title on “discoursing learnedly” and “composing beautifully.”

[20] Gioseffo Zarlino’s second book of motets, the Modulationes sex vocum, appeared in 1566 (Illustration 6). Published by Rampazetto, the dedication of the print was signed by Philipo Zusberti, a recently hired singer in the choir of San Marco. Although somewhat lengthy, I would like to quote the complete dedication, from which I will highlight three passages.

To my most brilliant lord procurators of Saint Mark’s concerning those matters broached above. [May you have] felicity everlasting.

Having collected from various places certain extremely beautiful musical compositions, Most Brilliant and Most Noble Senators, composed once upon a time by the Most Famous musician Gioseffo Zarlino of Chiogga, I thought it would be worthwhile to make them public. For the author himself, being an utter stranger to any form of ambition, was so far from ever letting them get out that there is danger he may become angry with me for doing so.

But however that may be, it will nevertheless be beneficial to take thought, to the best of my ability, both for all musicians and especially for the reputation of my mentor; because long ago now he so taught me the arts of music as it will never come to pass that I could feel regret; besides which, so humane and pious is he that he will easily forgive me this offense, especially since he knows that I should not have done it except by reason of piety. But neither do I regard this as a rash deed, for after that distinguished book to which he gave the title On the Institutes of Harmony in which he seems to discourse on the discipline of music with such learning and eloquence that no one yet (and let this be said with the indulgence of all) has treated this particular subject more clearly or fully, who is there that would not long for the second book of compositions? And all the more so, because he very frequently makes mention of these matters in the earlier book? Another motive is that all should understand that this same artist is able to discourse learnedly on the theoretical aspects of music and to produce the most lovely of all compositions. But away with the rabble of backbiters and (to speak more truthfully) that pernicious pestilence that is never slow to detract from the fame of others; wherefore I thought it best to take refuge with you, excellent Senators, so that you might, by your unsurpassed authority, together with me protect from the venomous carping of these people the same man to whom you, not without God’s will, assigned such an office as the leadership of all the musicians in the Choir of Saint Mark’s. For with you as our patrons we shall have no fear of such barking sycophants.

And furthermore, lest anyone think that I am doing more on others’ behalf than on my own, I shall very shortly publish certain compositions of my own, such as they are, which are to be presented to you as by your right, you to whom just as before I now dedicate and commit both myself and all my possessions. That you will aid me by your patronage and protect me by your authority I ask you and trust that it will be so.

May God Almighty keep and protect you for your own good and that of the Republic. Farewell.

Venice, March 1566.

Your humble servant, Philippo Zusberti, musician in the Choir of San Marco. (Translation from Judd 2000, 248–49)

[21] Having begun by reference to this collection of beautiful compositions (“Having collected from various places certain extremely beautiful musical compositions”), Zusberti declares:

For the author himself, being an utter stranger to any form of ambition, was so far from ever letting them get out that there is danger he may become angry with me for doing so.

Here Zusberti alludes to Zarlino’s character in ways that would seem to be wishful thinking with regard to what we know about Zarlino (a kind of rhetoric of opposites): Zarlino’s career trajectory suggests that he was, in fact, highly ambitious. The comment that he was “far from ever” allowing these works out also seems to fly in the face of Zarlino’s penchant to publish, although perhaps it may be a way to link this collection to Zarlino’s mentor Willaert and the well-known history of the publication of the Musica Nova.

[22] Zusberti goes on to provide a three-fold rationale for the publication of the motets in this collection. It is a rationale that conveniently references Zarlino’s earlier works as well as his new appointment at San Marco: First, after directly referencing the Istitutioni harmoniche, Zusberti asks, “Who is there that would not long for the second book of compositions?” Secondly, Zusberti acknowledges that Zarlino very frequently makes mention of these motets in the earlier Istititioni, another reason to make the works known. And finally, he asserts “that all should understand that this same artist is able to discourse learnedly on the theoretical aspects of music and to produce the most lovely of all compositions . . . ” To “discourse learnedly” and “compose beautifully” (to which I will also add in a moment: “administer benignly” . . . ).

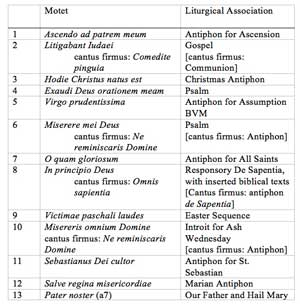

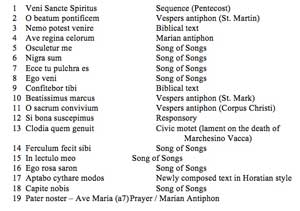

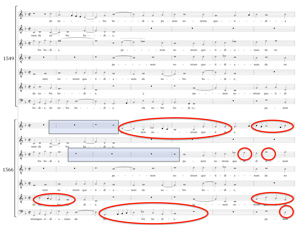

[23] Even had the 1566 motet print not survived, we would have had more than an inkling of what it contained (see Illustrations 7 and 8). Two motets had already been published in 1549. Another six that eventually appeared in this collection were cited in the 1558 edition of Le istitutioni harmoniche (which commensensically we might imagine to have been published in a now unknown print that preceded, or at least accompanied the publication of the treatise if we did not have Zusberti’s testimony about the works not being released). And two others were cited in the revised 1573 edition of the treatise. Finally, two of the motets not otherwise published or cited by Zarlino appeared in manuscript collections.

|

Illustration 7. Contents of Modulationes sex vocum (click to enlarge) |

Illustration 8. Citations and concordances for the motets in Modulationes sex vocum (click to enlarge) |

Illustration 9. Canons in the Modulationes sex vocum

(click to enlarge)

[24] So in the end, there is only one work in this collection whose existence would have been wholly unknown to us had this motet book not survived in its single known copy. The focus of this print is clearly on counterpoint, with canonic inscriptions for each work (see Illustration 9) that harken to the counterpoint book (Part III) of the Istitutioni. So strong, in fact, is the association of these works with the counterpoint section of the treatise, that it seems reasonable to assume that Zarlino may well have composed most of the works while he was actively engaged in the writing of the Istitutioni or perhaps even before, with the Istitutioni merely cataloguing a compositional exploration.

[25] However, the actual publication of the 1566 motet print may have more to do with a particular moment in Zarlino’s career. Following shortly after his appointment at San Marco, it would seem from the dedication of the print that at least some had voiced criticism about Zarlino’s appointment—perhaps even bringing his credentials into question—and the publication was intended to silence those critics (and perhaps even hold the procuratori responsible for his defense).

But away with the rabble of backbiters and (to speak more truthfully) that pernicious pestilence that is never slow to detract from the fame of others; wherefore I thought it best to take refuge with you, excellent Senators, so that you might, by your unsurpassed authority, together with me protect from the venomous carping of these people the same man to whom you, not without God’s will, assigned such an office as the leadership of all the musicians in the Choir of Saint Mark’s. For with you as our patrons we shall have no fear of such barking sycophants.

Illustration 10. Gentile Bellini, Procession in the Piazza San Marco, 1492, Gallerie dell'Accademia, Venice

(click to enlarge)

[26] It is not hard to imagine the source of at least some of these criticisms when one remembers that Zarlino had taken arguably the most prestigious musical post in all of Europe when he was appointed at San Marco (see Illustration 10). And it is also worth remembering that he assumed the position after Willaert’s long tenure (see Illustrations 11a and 11b) and Cipriano de Rore’s brief and tumultuous stint as maestro di capella. These were two men of extraordinary musical reputations in their lifetime. The last years of Willaert’s tenure were plagued by chronic absenteeism by musicians, who hired poorly-trained substitutes while they themselves slipped away for higher paying gigs. A five-month vacancy after Willaert’s death did not help matters, and the total reorganization of the chapel upon Rore’s appointment only exacerbated the eroding discipline and chaos. Zarlino’s appointment signaled an attempt to end nearly a decade of disarray.(6) When hiring Zarlino, the procuratori said they were looking for a person “not just excellent in the practice of music, but someone superior to the other musicians, prudent and modest in the fulfilling of his duties” (quoted in Edwards 1998, 393). His initial appointment was a two-year contract with the possibility of renewal for three additional years. Not a lot of time to turn around an unruly bunch of singers and instrumentalists! Throughout his tenure, from the records of the procuratori, we really learn about Zarlino, the administrator (a story I may be especially attuned to or sympathetic to as a present-day administrator).(7)

|

Illustration 11a. Anonymous 18th-century portrait of Adriano Willaert, possibly after the engraving in the Musica Nova. (Conservatorio Statale di Musica G.B. Martini, B 38530 / B 11861) (click to enlarge) |

Illustration 11b. Title page of Adriano Willaert, Musica Nova (Venice: Gardano, 1559) (click to enlarge) |

[27] If on its surface Zarlino’s motet book from 1566 was about establishing or cementing his credibility as maestro di capella at San Marco during the “probationary period” of his initial contract, it was also—explicitly through its preface as well as implicitly with its inclusion of works from the Istitutioni and the profusion of canons—a set of compositions with a clear theoretical bent and an overt association to a specific part of Zarlino’s theoretical oeuvre: Book III of the Istitutioni (Illustration 12a), known most familiarly to many of us through Guy Marco’s translation (Illustration 12b; Zarlino 1968 [1558]).

|

Illustration 12a. Gioseffo Zarlino, Le istitutioni harmoniche (1558), opening of Part III. (click to enlarge) |

Illustration 12b. Cover of Guy Marco, The Art of Counterpoint (click to enlarge) |

Illustration 13. Part III, Le istitutioni harmoniche, Marco translation, and Title page of Modulationes sex vocum

(click to enlarge)

[28] As I remarked earlier, Zusberti was a recently hired member of the choir (see Ongaro 1986). He would certainly have us believe from his preface that these works serve multiple functions: first and foremost illustrating that a composer who can “discourse learnedly” can also “compose beautifully.” And we might—given their many citations in Zarlino’s treatise and their appearance after its publication—be tempted to see in these works a kind of anthology to accompany the treatise. (One thinks for example of the modern day proliferation of bundled packages of accompanying materials for pedagogical textbooks, each of which has its own musicianship companion, accompanying anthology, instructor guide, website, and so forth; see Illustration 13.)

[29] Yet, Zarlino’s treatise sits in a complicated relationship to his compositions. The two books of motets effectively bookend the treatise equidistantly, the second published in 1566, some eight years after the treatise, and the first published in 1549, nine years before the treatise (Illustration 14). So I would like now to turn briefly to the predecessor of the treatise, the 1549 book and the compositions it contains (Illustration 15), before returning to the works from 1566.

|

Illustration 14. Zarlino’s two motet anthologies and Le istitutioni harmoniche (click to enlarge) |

Illustration 15. Title page of Gioseffo Zarlino, Musici quinque vocum moduli (Venice: Gardano, 1549) (click to enlarge) |

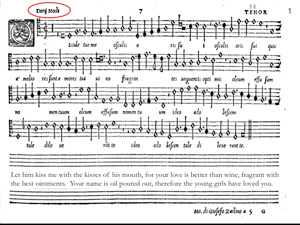

Illustration 16. Gioseffo Zarlino, Osculetur me (Musici quinque vocum moduli), tenor with modal indication

(click to enlarge)

Illustration 17. Gioseffo Zarlino, Musici quinque vocum moduli, Table of contents

(click to enlarge)

[30] In brief: the most striking feature of the 1549 print is the inclusion of printed dodecachordal modal labels in the tenor partbook (Illustration 16), connecting these works to Glarean’s Dodecachordon. Appearing a scant two years after the treatise’s publication, these labels hint at the genesis of Zarlino’s own twelve-mode theory, which was to be published almost a decade later. Other aspects of the print tie its works closely to the mid 1540s, the period after Zarlino arrived in Venice, when he was not only studying composition but also Greek, Hebrew, and theology. The collection contains thinly veiled autobiographical pointers and wears its learning anything but lightly: a civic motet connected to Chioggia; a pseudo-Horatian ode befitting Zarlino’s classical learning; antiphons proper both to St. Martin, patron of the Chioggia church where Zarlino was trained, and to St. Mark, patron of the basilica in Venice; overt references to compositions by Verdelot and Willaert, among others, and so forth (Illustration 17). But the umbrella under which all of this exists is a modal one. The works are ordered by what Powers has labeled as tonal types—that is, markers of system, ambitus, and final, which represent modes (Illustration 18). These are precisely the modal categories that Zarlino will take over as the subject matter of the fourth and final book of the Istitutioni, dropping Glarean’s Greek names and instead simply numbering them. Just as the preoccupation of the 1566 motet book is the counterpoint that makes up the third book of the treatise, so the modes are the overt signposts of this collection (Illustration 19).(8)

[31] Yet as I have shown elsewhere (Judd 2000, 2001, and 2002), the relationship of these works and the treatise is far more complicated because the majority of the motets from the collection can be shown to belong to an aborted eight-mode Song of Songs motet cycle, an extraordinary theoretical and theological undertaking that was deliberately and effectively effaced in the publication of the works.

|

Illustration 18. Gioseffo Zarlino, Musici quinque vocum moduli, Tonal Types and Modal Labels (click to enlarge) |

Illustration 19. Part IV, Le istitutioni harmoniche, Cohen translation, and Title page of Musici quinque vocum moduli (click to enlarge) |

Illustration 20. Osculetur me (Musici quinque vocum moduli), Tenor

(click to enlarge and hear the audio)

Illustration 21. Part 3 of the Istitutioni harmoniche and Modulationes sex vocum 1566—the “counterpoint” pairing; Part 4 of Le istitutioni harmoniche and Musici quinque vocum moduli 1549 - the “mode” pairing

(click to enlarge)

Illustration 22a. Pater noster—Ave Maria, Tenor. Musici quinque vocum moduli

(click to enlarge)

Illustration 22b. Pater noster, Quintus. Modulationes sex vocum

(click to enlarge)

Illustration 23. Pater noster (1549). Opening canon: Fuga duplex. Trium temporum in diapente et sex temporum in diatessaraon

(click to enlarge)

[32] Osculetur me, the fifth motet in the book used above as an illustration for its modal attribution (see paragraph 30), is the first work of this cycle, and I have provided a recording of the prima pars of the motet—as a backdrop to our further discussions and as a chance to introduce Zarlino the composer. Illustration 20 is of the tenor voice part; a recording by Ensemble Plus Ultra accompanies the illustration. I have also provided a text translation on the illustration. The tenor starts after three breves of rest and is the third voice to enter the texture. Although I wish I could take time to discuss this piece (or at least play the secunda pars so as not to leave you hanging), I want to take us on to another, and so I will simply encourage you to check out my edition (Judd 2006) and the recording by Ensemble Plus Ultra!(9)

[33] At the very minimum, the relationship of Zarlino’s two books of motets to the treatise they frame chronologically is a complicated, layered, and non-linear one, even as one can see the ways in which Zarlino seems on the one hand to work out his theory in the compositions and at the same time to work out his compositions in the theory. Nevertheless, the priorities of the two compositional collections are clear—the modal preoccupations are nowhere in evidence in the 1566 collection, while the canonic virtuosity of the later book hardly features in the first book. And the relationship is a remarkably fluid one (Illustration 21).

[34] In that context, I have been fascinated with one work which offers a particular point of contact between the two motet books and the treatise. The seven-voice Pater noster – Ave Maria concludes both of Zarlino’s motet collections and was also the most frequently cited of his own works in Le istitutioni harmoniche (see Illustrations 22a and 22b). The motet is Zarlino’s longest and most complex, and one of the few works for which a manuscript copy is also known to survive. The context of the Pater noster is complicated: the motet belongs to a sixteenth-century tradition of Pater noster – Ave Maria motet settings ranging from Josquin to Lasso and beyond, and the 1549 and 1566 versions of the motet provide evidence of significant reworking.(10)

[35] Like the settings by Josquin and Willaert to which it gestures, Zarlino’s motet relies on a cantus firmus set canonically, and this most basic compositional decision would seem to gesture overtly to both works. But if gesturing overtly, there is also the sense of one-ups-manship in Zarlino’s creation of a canon that generates not one, but two additional voices, resulting in a composition notated for five voices and realized for seven voices.

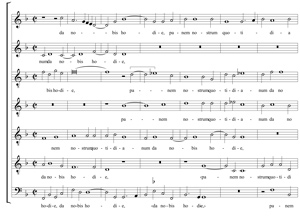

[36] Zarlino explains when he refers to this piece in the Istitutioni that “the subject of the three voices that sing in fugue is the second rather than the first to be heard” (Zarlino 1968 [1558]). You can see the rubric from each of the set of partbooks. Note that in the 1549 partbook, two voices appear on a single page (Illustration 22a); in 1566, these appear in separate partbooks (Illustration 22b). Illustration 23 shows that the soggetto appears in the tenor “at pitch”; the sextus anticipates by three breves at the fifth above, while the septima vox follows by three breves at the fourth above. As you can see from the opening of the realization of the canonic scaffold, the cantus firmus is set in relatively long note values and the three-breve distance results in minimal overlap of the canonic voices, generally for only a minim or a breve. Similarly, new phrases of the chant dovetail with previous phrase, if at all, for only a minimal span, as can be seen by the opening of the canonic framework.

[37] Of a total of 254 measures in the modern transcription of Zarlino’s Pater noster, more than two-thirds (174) of the 1666 version exhibit some change from the 1549 version. The variants between the two versions do not lend themselves to easy comparison via a collated edition or the usual mechanisms of critical commentary. The stable element of the composition is the underlying canon responsible for three of the seven voices. There is one change to the cantus firmus, and even this distributes the cantus firmus over exactly the same number of breves, leaving the underlying scaffold unchanged.

[38] Some of the changes to the two versions of the Pater noster may be grouped broadly into general categories such as correction (e.g., voice leading or dissonance treatment) or “updating” (e.g., the use of cadential ornaments), but the element associated with most of the changes has to do with text: its distribution, underlay, articulation, and rhythmic declamation. I have made this argument in much greater detail in an article in a Festschrift for Eugene Narmour (Judd Forthcoming), but I would like to just highlight a few such examples for you as support for claims I would like to advance about the two versions of this piece.

Illustration 24. Pater noster, opening duo, measures 1–18 (1549 and 1566)

(click to enlarge and hear the audio)

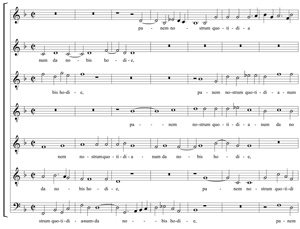

[39] The opening duo between a pair of non-canonic voices, the altus and quintus, offers a good opportunity for illustrating the nature of the revision between the two versions. I have highlighted four examples of changes in pitch and rhythm in Illustration 24.

(1) A suspension figure ornamentation is removed and a semibreve changed to two minims in the tenor of 1566

(2) a semibreve is altered to a dotted minim and semiminim in the altus of 1566; a rest is inserted in the tenor

(3) the counterpoint has been reworked so that the voices have switched parts; a rest is inserted in the altus in 1566

(4) the altus ends early in 1566, with rests substituted

Illustration 25. Pater noster, text comparison 1549 and 1566

(click to enlarge)

Illustration 26. Pater noster, measures 64–70 (1549 and 1566)

(click to enlarge)

[40] Concern for textual placement and articulation provides a plausible motivation for these musical changes. Namely, the removal of the ornamented figure in (1) allows placement of additional syllables of text; the rests and voice exchange of (2) and (3) highlight the articulation of the repetition of the first phrase of text. The rests at (4) occur because the new underlay of text requires setting fewer syllables.

[41] Close comparison of passages like this in the two versions leads to the conclusion that the revisions are an accommodation of music to words, not words to music. An outline of the opening text highlights the principles that appear to have driven this re-accommodation of music to words in the later version. Text is repeated less frequently and repetition of small sub-phrases of text is generally eschewed (see Illustration 25). The musical corollaries to these general principles follow: overall, fewer syllables of text are set—and they are set more syllabically—with the result that voices sometimes drop out of the texture, which in turn becomes somewhat less dense. Beginnings of new phrases of text now have entries that are more carefully set apart and more clearly defined rhythmically. Deliberate effort has been made to align the phrases of text more nearly among voices.

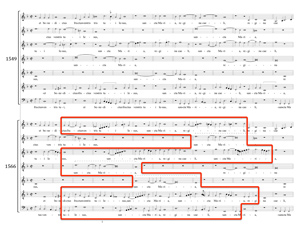

[42] Illustration 26, taken from measures 64–70, shows one of the more extended re-compositions, involving the redistribution of parts among the four non-canonic voices and the creation of a quasi imitative texture. The addition of rests has been highlighted with blue boxes and the revisions to parts with red circles. Illustrations 27a and 27b provide the two scores with linked sound files.

|

Illustration 27a. Pater noster, measures 64–70 (1549) (click to enlarge and hear the audio) |

Illustration 27b. Pater noster, measures 64–70 (1566) (click to enlarge and hear the audio) |

Illustration 28. Pater noster, measures 190–203 (1549 and 1566)

(click to enlarge)

[43] The compositional outcome is greater demarcation within the texture, both of the initial word of a phrase of text, and the emphasis on the larger textural unit. The motet moves fluidly in and out of these recomposed and adjusted passages, coming back together at points of articulation of new phrases of text in the cantus firmus, which, in turn, provides the scaffolding that defines the identifiable units or sections of the composition. The larger flow of the text itself is further highlighted in the placement of melismas, which are less frequent in the 1566 version.

[44] A single section of the secunda pars of the motet is completely recomposed; see the comparison in Illustration 28. In the later version from 1566, the cantus firmus has been slightly modified rhythmically and a pitch inserted. As counterpoint, a new clearly identified motive is used in imitation in the free voices, highlighting the opening of the second verse of text on the words “sancta Maria.” This is the only such complete re-composition in the motet and it has been carefully inserted within the original temporal framework of the canon. Illustrations 29a and 29b provide the two scores with linked sound files.

|

Illustration 29a. Pater noster, measures 190–203 (1549) (click to enlarge and hear the audio) |

Illustration 29b. Pater noster, measures 190–203 (1566) (click to enlarge and hear the audio) |

[45] As illustrated through these examples, the alterations are not of a single sort, nor do they seem to represent uniform musico-stylistic priorities: instances of filling in of lines with melodic ornamentation appear side by side with simplification or stripping away of melodic elaboration; cadential suspensions and dissonance figures are both added and removed, and so forth. If this represents an “updating” of the Pater noster, that updating seems to revolve around the way in which the text is distributed and the way in which the note values have been assigned to that text. This re-composition departs from a work in which the assignment of text syllable to music is remarkably unambiguous; nevertheless the music is altered in the service of the text.

Illustration 30. Pater noster (1549)—Le istitutioni harmoniche (1558)—Pater noster (1566)

(click to enlarge)

[46] And that brings me back to the ways in which this composition and the two books of motets in which it appears frame Zarlino’s theoretical text (Illustration 30). While the first motet book is focused on “mode” and the second on “counterpoint,” the substantial alterations to this composition have nothing to do with those concerns.

[47] The reworking of this motet in appearances seventeen years apart, within Zarlino’s relatively small compositional output, and the complicated means by which it interacts with different versions of Le istitutioni harmoniche, point to fascinating aspects of the interrelationships among the various pieces of Zarlino’s oeuvre.

[48] In this particular instance, despite the fact that the motet concludes an anthology overtly connected to mode as well as one on counterpoint, and despite the fact that it is cited in both the relevant sections of the treatise, I believe that it points us most directly to a different part of the treatise: the brief final chapters of Le istitutioni harmoniche which address a number of practicalities in relation to mensural polyphony. Here Zarlino addresses what the composer should observe when composing, how harmonies are accommodated to words, how note values are assigned, and so forth.(11) These chapters offer a concise compendium of practical advice to composers, while also firmly situating the preceding discussion of counterpoint and the modes. And attention to composers is always balanced by attention to performers or observers: what is necessary for composing, what is necessary for singing, what is necessary for judging. Like so many parts of books three and four of Le istitutioni harmoniche, these chapters present a prescriptive version of a situation that was clearly in flux. If the Pater noster can be taken in any sense to be exemplary, the compositional approach clearly shifted in significant ways between the publication of the first anthology and the publication of the motet book of 1566, but the particular role played by the intervention of the theory treatise is uncertain.

[49] What Zarlino actually has to say about setting texts is minimal and hard to put to either descriptive or prescriptive use given its lack of specificity. For example:

The whole task consists of assigning note values to given words, and it is essential in a composition that by this means the notes be described and notated in such a way that the sounds and tones can be performed in every melodic line. (Zarlino 1983 [1558], 97)

Illustration 31. Pater noster facsimiles of 1549 and 1566 in comparison

(click to enlarge)

It would seem that this is exactly the task represented in the later version of the Pater noster. That task included not merely fitting syllables of phrases to the notes that had already been provided nor simply of understanding how to allocate the syllables in the case of minimal or ambiguous underlay. Rather, this recomposition departs from a work in which the assignment of text syllable to music is remarkably unambiguous—indeed the 1549 print is exceptional for its clarity and I have elsewhere argued (Judd 2006 and 2007) for its preoccupation with the clear declamation of text by individual voices. Yet in 1566, the music is altered in the service of that same text. In that alteration, we have a rather unusual perspective, closely tied to changing preferences. Taken in their entirety, the two versions of the Pater noster betray significantly different approaches to text setting, neither of which is actually in conflict with what Zarlino says about text setting in the treatise, nor which can fully stand as an exposition of text setting principles. Illustration 31 removes the treatise from Illustration 30, placing the two versions of Pater noster side by side. As it turns out, the compositions in the “modal” motet anthology cannot be taken at face value to be an exposition on mode, nor those in the “counterpoint” anthology to be an exposition of counterpoint. In these two versions of the Pater noster, we see a wonderful complication of the theoretical exposition of text setting.

[50] As Bonnie Blackburn trenchantly observed, in the relationship of words and music, both the specifics of the “connection between a syllable and a note or notes” and the broader sense of the way in which a text “is presented in music” are “aspects of that elusive concept that is central to an understanding of music in an age where autographs hardly exist and variant versions are the norm: the composer’s intention” (Blackburn 1989, 161).

[51] Zarlino’s modal theory as presented in Le istitutioni harmoniche represented an ongoing assimilation of tradition, practice, and his own creative theorizing. This is seen in his engagement with Glarean and others, sometimes acknowledged, more often not, and is intantiated by means of an eight-mode repertory versus twelve mode duos, among other means. Similarly, Don Harrán (1986) has shown Zarlino in dialogue with Lanfranco in his rules for text-setting, moving toward codification, while reinterpreting (or perhaps simply interpreting) inherited tradition. The Pater noster in its two versions offers the compositional equivalent of such assimilation of tradition, practice, creative theorizing, and changing priorities. The Audio Example below provides the Prima pars of the Pater Noster from 1566.

Audio Example. Pater noster (1566), Prima pars, Singer Pur 2013

[52] Reading from a theorist’s writings to a group of compositions is always a task fraught with difficulty, especially when there is a chronological separation in the appearance of the two. Equally challenging is the prospect of projecting from the works of a composer to the basis of a theoretical tradition. Although it might seem a less difficult process when the theorist and composer are a single person, it is important to resist the easy assumption that the relationship is transparent.

[53] Zarlino himself has explicit comments to offer about the relationship of theory and practice:

Accordingly, just as it would be insane to rely on a physician who does not have the knowledge of both practice and theory, so it would be really foolish and imprudent to rely on the judgment of [a musician] who was solely practical or had done work only in theory (Zarlino 1983 [1558], 106).***

Theory without practice is of small value, since music does not consist only of theory and is imperfect without practice. This is obvious enough. Yet some theorists, treating of certain musical matters without having a good command of the actual practice, have spoken much nonsense and committed a thousand errors. On the other hand, some who have relied only on practice without knowing the reasons behind it have unwittingly perpetrated thousands upon thousands of idiocies in their compositions. (Zarlino 1983 [1558], 226)

[54] Yet, at the same time we glimpse the explicit way in which Zarlino is prepared to remake or recast his own past and his own past work. In Zarlino’s works, we witness a complicated dance in the intersection of his life as an organist, composer, a writer about music, and an administrator of the cappella of San Marco, not to mention a priest.

Illustration 32. Interrelationships of Zarlino’s career and publications

(click to enlarge)

Illustration 33. Map of Zarlino’s career and publications highlighting the role of Le istitutioni harmoniche

(click to enlarge)

[55] So taking the Modulationes of 1566 as a starting point, the works on the one hand point to Zarlino’s recent employment at San Marco, but also back to the Istitutioni of 1558. At the same time they point specifically through the Pater noster to the motets of 1549. And they point forward to the Istitutioni of 1573. I have tried to represent these layers in Illustration 32.

[56] But even this suggests an illusory clarity, with its clearly drawn boundaries and Zarlino sharply drawn and foregrounded along with San Marco and the musical world it encompassed, when of course our reality has an idealized version of a treatise as the object most clearly in focus (Illustration 33).

[57] I confess that when I began reading Zarlino’s treatise through the lens of its music examples, I never imagined that the process would take me so deeply into his compositions, to reading sixteenth-century commentaries and translations of the Song of Songs, to editing the works, to a recording project, and to editing more works and, yet to another recording project, and from those back yet again to the treatise. I hope that my journey has not been a quixotic one, but I am reminded in this search for connecting and elucidating theory and practice of the Jorge Luis Borges short story, “Pierre Menard, Author of the Quixote.” Obviously we can never know “enough,” yet I do believe that understanding Zarlino as a composer can help us reimagine or at least more richly imagine him as a theorist, just as knowing Zarlino as a mathematician may also inform that perspective of his work and so forth. (I have not yet resorted to writing the paper entitled “Zarlino: the administrator,” which feels a bit too self-serving in my present occupation!) Above all, I would argue that this kind of exploration serves as a reminder that writings about music can function as transhistorical documents in ways which complicate the repertories they explicitly engage.

[58] I would like to conclude with a simple elliptical turn to the texts I referenced near the opening of this talk. I confess that I have not yet discovered whether, in Bent’s dichotomy, I am a music theorist who is interested in history or a historian who is interested in music theory. Fortunately, in my case the blurred boundaries seem to have been career-enabling and enriching rather than career ending. And returning to the 8 a.m. freshman theory class to which I made fleeting reference at the start of this address, it is perhaps revealing that the title of the rather unconventional textbook for the first class I took in college was Perspectives in Music Theory: An Historical-Analytical Approach (Cooper 1973), a title which in some ways sums up my career to date (the moral being: you never know just how much influence you wield in those 8 a.m. freshman theory classes!). This description reflects my own proclivity for working in detail at the local level and my sense that this allows the most profitable move to the bigger picture in a reflexive, interpretive turn. But it also stems from the pragmatic turn to which Powers alluded: “Relationships between theory and practice are not a priori, they are ad hoc, so any eventual confrontations of theory and practice ought to be pragmatic, and on a case-by-case basis.” I hope, at least in the case of Zarlino, that I have offered some new perspectives for contemplating that relationship.

[59] It remains, then, merely to conclude with one last quotation from Powers’s keynote address: “I must thank you, humbly at last, for indulging my self-indulgence. On to the bar!”

Cristle Collins Judd

Bowdoin College

Department of Music

cjudd@bowdoin.edu

Works Cited

Bent, Ian. 1992. “History of Music Theory: Margin or Center.” Theoria 6: 1–21.

Blackburn, Bonnie. 1989. Review of Word-Tone Relations in Music Thought from Antiquity to the Seventeenth Century by Don Harrán and Essays on Italian Poetry and Music in the Renaissance, 1350–1600 by James Haar. Journal of the American Musicological Society 42: 161–72.

Cooper, Paul. 1973. Perspectives in Music Theory: An Historical-Analytical Approach. New York: Dodd Mead.

Edwards, Rebecca. 1998. “Setting the Tone at San Marco: Gioseffo Zarlino amidst Doge, Procuratori and Cappella Personnel.” In La Cappella Musicale di San Marco nell’età moderna: Atti del convegno internazionale di studi, Venezia, 5–7 settembre 1994, ed. Francesco Passadore and Franco Rossi, 389–400. Venice: Fondazione Levi.

Einstein, Alfred. 1971. The Italian Madrigal. Translated by Alexander H. Krappe, Roger H. Sessions, and Oliver Strunk. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Harrán, Don. 1986. Word-Tone Relations in Musical Thought from Antiquity to the Seventeenth Century, Musicological Studies and Documents 40. Neuhausen-Stuttgart: American Institute of Musicology.

Judd, Cristle Collins. 2000. Reading Renaissance Music Theory: Hearing with the Eyes. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

—————. 2001. “A Newly Recovered Eight-mode Motet Cycle: Zarlino’s Song of Songs Motets,” Théorie et analyse musicales 1450–1650, ed. Anne-Emmanuelle Ceulemans and Bonnie J. Blackburn. Louvain-le-Neuve: Université Catholique de Louvain, 229–70.

—————. 2002. “Renaissance Modal Theory: Theoretical, Compositional, and Editorial Perspectives,” in The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory, ed. Thomas Christensen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 364–406.

—————. 2006. Gioseffo Zarlino, Canticum canticorum Salomonis. Introduction and critical edition, Recent Researches in Music of the Renaissance. Madison, WI: A-R editions.

—————. 2007. Gioseffo Zarlino, Motets from Musici quinque vocum moduli (1549). Introduction and critical edition, Recent Researches in Music of the Renaissance. Madison, WI: A-R editions.

Judd, Cristle Collins. Forthcoming. “‘How to Assign Note Values to Words’: Gioseffo Zarlino’s Pater Noster – Ave Maria (1549 and 1566).” In Festschrift for Eugene Narmour, ed. Lawrence Bernstein and Alexander Rozin. New York: Pendragon.

Judd, Cristle Collins and Katelijne Schiltz, eds. Forthcoming. Gioseffo Zarlino, Motets from the 1560s. Recent Researches in Music of the Renaissance. Madison, WI: A-R Editions.

Kirkendale, Warren. 1970. “New Roads to Old Ideas in Beethoven’s ‘Missa Solemnis,’” The Musical Quarterly 56: 665–701.

Lester, Joel. 1992. Compositional Theory in the Eighteenth Century. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ongaro, Giulio. 1986. “The Chapel of St. Mark's at the Time of Adrian Willaert (1527–1562): A Documentary Study.” PhD diss., University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill.

Palisca, Claude. 2013. “Zarlino, Gioseffo.” In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. Accessed August 22. http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/.

Powers, Harold. 1993. “Three Pragmatists in Search of a Theory.” Current Musicology 53: 5–17.

Rameau, Jean-Philippe. 1971 (1722). Treatise on Harmony. Translated by Philip Gossett. New York: Dover.

Reese, Gustave. 1954. Music in the Renaissance. London: J.M. Dent.

Wienpahl, Robert. 1959. “Zarlino, the Senario, and Tonality.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 12, no. 1: 27–41.

Zarlino, Gioseffo. 1549. Musici quinque vocum moduli. Venice: Gardano.

—————. 1968 (1558). The Art of Counterpoint: Part Three of Le Istitutioni Harmoniche. Translated by Guy A. Marco and Claude V. Palisca. New Haven: Yale University Press.

—————. 1983 (1558). On the Modes: Part Four of Le Istitutioni Harmoniche. Translated by Vered Cohen. New Haven: Yale University Press.

—————. 1566. Modulationes sex vocum. Venice: Rampazetto. Facsimile available at http://daten.digitale-sammlungen.de/~db/0007/bsb00074378/images/.

Discography

Discography

| Ensemble Plus Ultra. 2007. Gioseffo Zarlino: Canticum Canticorum Salomonis. Michael Noone, director. Glossa GCD921406, compact disc. |

| Ensemble Plus Ultra. 2007. Gioseffo Zarlino: Canticum Canticorum Salomonis. Michael Noone, director. Glossa GCD921406, compact disc. |

| Singer Pur. 2013. Gioseffo Zarlino: Modulationes sex vocum. Oehms Classics, OC873, compact disc. (www.singerpur.de) |

| Singer Pur. 2013. Gioseffo Zarlino: Modulationes sex vocum. Oehms Classics, OC873, compact disc. (www.singerpur.de) |

Footnotes

1. “The most important advances in sixteenth-century harmonic theory were made primarily by one man, Gioseffo Zarlino (1517–90), and it is safe to say that probably no theorist since Boethius was as influential upon the course of the development of music theory” (Wienpahl 1959, 27).

Return to text

2. “Among the many excellent sixteenth-century writers on music, Zarlino alone was preeminently influential on later theorists in numerous countries. His formulations, transmitted via his own magnum opus, the Istitutioni harmoniche of 1558, via manuscript translations, and via the writing of his pupils and others influenced by him, were authoritative for musicians in Italy, France, Germany, and England by the early seventeenth century. More than 160 years after its publication, ideas from the Istitutioni permeate early-eighteenth-century writings in several different theoretical traditions. And as late as the end of the nineteenth century, Hugo Riemann cited Zarlino as a source of parts of his harmonic theories” (Lester 1992, 8).

Return to text

3. “Zarlino: A celebrated writer on music whom M. de Brossard calls ‘the prince of modern musicians’” (Rameau 1971 [1722], Table of Terms, lv, cited in Lester 1992, 7).

Return to text

4. “[T]he theorist of his century and maybe of all centuries” (Einstein 1971, I:453).

Return to text

5. For a longer history of the reception of Zarlino’s compositions, especially in the theoretical literature, see Judd and Schiltz Forthcoming.

Return to text

6. The summary given here of events leading up to Zarlino’s appointment relies on Edwards 1998, 389–400, especially 391–93.

Return to text

7. Edwards (1998) provides an excellent overview of Zarlino’s administrative work in San Marco over the course of his career there.

Return to text

8. The image on the left hand side of Illustration 19 is from Vered Cohen’s translation (Zarlino 1983 [1558]).

Return to text

9. I collaborated with Michael Noone, director of Ensemble Plus Ultra for the first modern performances of these works, using my editions (Judd 2006 and 2007), at the Coloquio sobre Zarlino y los teóricos, Gijon Spain, July 18, 2004 and the Annual Meeting of the Renaissance Society of America, Clare College Chapel, Cambridge, April 9, 2005. In addition to the edition, I provided liner notes for the recording (Ensemble Plus Ultra 2007).

Return to text

10. For a detailed discussion of this motet and its antecedents, see Judd Forthcoming.

Return to text

11. These precepts are widely cited. See for example Harrán 1986.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2013 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason, Managing Editor

Number of visits: