Review of Matthew Bribitzer-Stull, Anthology for Analysis and Performance (Oxford University Press, 2014)

Mary Wennerstrom

KEYWORDS: analysis, performance, musical scores anthology

Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory

[1] Anthologies of musical scores for use in theory classes (as distinct from music history classes) have at least a fifty-year publishing history. One of the earliest, Charles Burkhart’s Anthology for Musical Analysis, appeared first in 1964, and was arranged chronologically. It included works from the late seventeenth century (Purcell) to the middle of the twentieth century (Babbitt), and was soon integrated firmly into the undergraduate curricula of many schools. After a decade or more of use, instructors began to worry that music students would know only a prescribed canon of musical compositions: heavy on piano repertoire with sonata form best modeled by the piano sonatas of Beethoven (particularly the first movement of op. 53, “Waldstein”) and with the nineteenth-century character piece best represented by Brahms’s Intermezzo in A major, op. 118, no. 2.

[2] Subsequent anthologies, and later editions of the Burkhart anthology, broadened the scope of repertoire to include music by women, examples from jazz and the popular music repertoire, and an expanded chronology: as far back as plainchant and as current as 2000 and beyond. Anthologies also grouped works by form and/or contrapuntal procedure, and arranged excerpts by harmonic content. Selected anthologies and editions published in the last ten years are listed at the end of this review.

[3] One of the newest anthologies is Matthew Bribitzer-Stull’s Anthology for Analysis and Performance (hereafter AAP), for use in the theory classroom. The author’s purposes are made clear in a Preface for the Instructor: the compositions included broaden the types of medium and genre by including a wide range of instrumental music and deemphasizing piano, string quartets, and lieder. Bribitzer-Stull believes that the vast majority of his selections can be performed live in class, requiring “only the performing forces and technical abilities present among students in freshman and sophomore theory courses” (xiv). Such live musical experiences can facilitate reciprocal analytical and performance insights.

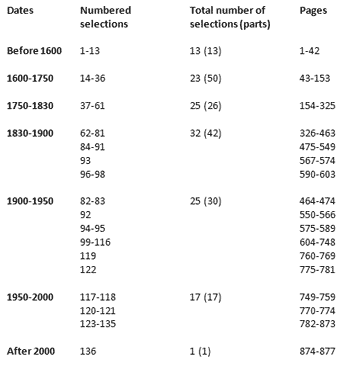

Example 1. Distribution of selections by dates of composition

(click to enlarge)

[4] Bribitzer-Stull has assembled a huge number of examples, which are presented basically in chronological order. Example 1 shows the distribution of selections by date of composition, indicating the numbered selections from the chronological list of pieces by composer, the total number of pieces (and in parentheses the number of movements or separate sections) in each time grouping, and the page numbers. There are 136 numbered selections, over half of them written since 1830. At 910 pages (877 pages of music plus appendices), AAP is certainly one of the largest anthologies available (and at over five pounds, one of the heaviest!).

[5] Each composition is preceded by brief commentary, including short references to analytical procedures and connections to performance. The Preface for the Instructor (xv) suggests several ways to relate performance and analysis, and the Appendix applies these ideas to a 50-minute lesson plan for Robert Schumann’s “Widmung,” including a performance at the beginning and end of the class interwoven with textual, formal, motivic, harmonic, and tonal analysis. Additional sections at the end of AAP include a glossary of foreign terms, a bibliography (“Works Cited”) of books and articles about analysis and performance (unfortunately not mentioned in the Contents, and buried on pages 884–885 under a heading of “Credits,” which are not included), an index of pieces by instrumentation, and a very long index of compositional materials and techniques. This last index requires double referencing: the item (term, chord type, form, etc.) is referenced by number in the chronological list of pieces by composer and by measure number, requiring the reader to refer back to the Contents for page numbers.

[6] The anthology includes works by composers not normally studied in music theory classes. Compositions by Giovanni Battista Pescetti, Anton Reicha, Ferdinand David, Jean-Baptiste Arban, Alexandre Guilmant, and Victor Ewald share space with those of more widely-known composers. Bribitzer-Stull is obviously intent on expanding the kinds of instrumental repertoire studied, with an emphasis on wind and brass solo and chamber music. He is not so interested in other kinds of diversity: no jazz, musical theater, or popular excerpts are included and there are only four compositions by women. Piano works are downplayed: Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven are represented by a total of four movements from piano compositions, Chopin’s only entry is two preludes from op. 28, and no piano music by Robert Schumann is included. The author comments in the Preface:

The pieces selected are ones many undergraduates will already know from work in private lessons or ensembles. Some of these lie outside what most would consider the established canon of masterworks, but two merits of these peripheral repertories come to mind: they engage the rich bodies of works often known only to players of the instruments for which they were written, and they may provide negative examples (many of us in selecting music for analysis forget that bad music provides different opportunities for learning and growth than does good). (xiv)

The author’s desire to relate analysis and performance is certainly laudable, although the benefits of presenting “bad music” for analysis are less clear.

[7] Bribitzer-Stull mentions that “all but a few scores in this anthology have been reset” (xv) and that “a listening list has been established on Naxos Music Library under ‘Music Anthology for Analysis and Performance’” (xi). In September 2013 the author sent a message to the members of the Society for Music Theory, apologizing that the Naxos playlists were available only for those who have a University of Minnesota account. He also mentioned that Oxford University Press was going to launch a website for discussion of the book. As of this writing, the website is not active and the playlists are not available.

[8] The resetting of scores provides a uniform, generally clear typeface throughout and presumably avoids some copyright issues. An anthology that emphasizes the interaction of performance decisions and analysis, however, should have scores that are accurate and should indicate any editorial decisions that have been made. Unfortunately, AAP is marred by problems of all sorts in the scores, and sources for editions and transcriptions are non-existent. The kinds of obvious errors include C clefs on wrong lines (No. 2, Dies Irae) or missing altogether (No. 8, Dufay’s Nuper rosarum flores), a wrong note in the contratenor at the beginning of No. 10, Ockeghem’s Missa Prolationum (confusing the description of the canon at the unison), the jumble of incorrect right-hand lines in the development of No. 54, Beethoven’s “Waldstein” sonata (creating impossible harmonic patterns), and a wrong metronome marking and several wrong notes in both the saxophone and the piano reduction at the beginning of No. 122, Bernhard Heiden’s Moderato from Diversion for Alto Saxophone and Band (half note instead of quarter note = 120).(1)

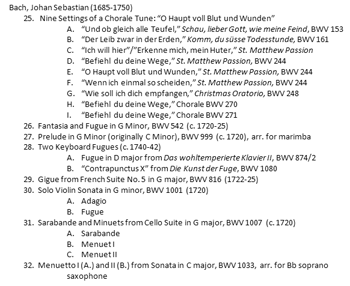

Example 2. Compositions in AAP by Johann Sebastian Bach

(click to enlarge)

[9] In order to look more closely at particular sections of the anthology, Examples 2 and 3 list works that Bribitzer-Stull chose for two repertoires included in most undergraduate core music theory curricula: compositions by Johann Sebastian Bach (Nos. 25–32) and compositions by Schoenberg, Webern, and Berg (Nos. 102–4, 110, and 112). Titles are as they appear in the chronological list of composers at the beginning of the book. The Bach selections (Example 2) illustrate the range of instruments included: chorales, an organ work (BWV 542), keyboard works, solo works for violin and cello, and arrangements for marimba and saxophone. Unfortunately no texted works are included; even the nine settings of “O Haupt voll Blut und Wunden” do not include the text. The author suggests that the chorales use an easily singable melody “rather than aiming for recondite word-painting figures.” However, the chromatic harmonization of “Und ob gleich alle Teufel dir wollten widerstehn” (“Tho’ all the fiends are striving o’er Heaven to prevail”), with its unstable beginning on a major-minor 4/2 chord, enlivens the text as contrasted to the diatonic and comforting harmonization of “Erkenne mich, mein Hüter, mein Hirte, nimm mich an” (“Remember me, and take me, my Shepherd, home to Thee”). If German and English texts were included, class performance could explore affects of certain chords and cadences, as well as various text continuations through fermatas. Even more problematic are the wrong notes in AAP that appear in seven of the nine versions.

[10] The organ Fantasie and Fugue begins on a clearly incorrect major ninth above a G minor chord and includes no performance indications. In contrast, the violin and cello movements are heavily edited, although no editor is referenced. The marimba and saxophone selections do not indicate the arranger, nor, in any of these instrumental works, how these movements fit into the complete composition. Although in the Preface Bribitzer-Stull says he has decided not to include specific performance suggestions, the detailed articulation marks in certain scores (such as some of these instrumental movements) are in fact performance decisions. It would be clearer to indicate the source of the edition and to listen to various performances to see how the markings are followed or contradicted. The cello suite as edited by Janos Starker, for instance, could be compared with his various recordings of the work and with other cellists’ performances, including in-class performances.

[11] Each of the Bach compositions is preceded by some commentary, suggesting analytical approaches (harmonic, tonal, and contrapuntal) and some performance sources, such as Joel Lester’s (1999) Bach’s Works for Solo Violin: Style, Structure, Performance. The keyboard works receive the least commentary. The text before the 12/16 Gigue from the French Suite No. 5 includes a statement that “The gigue is a lively simple-triple-meter dance that features leaping figures” (126), a metric comment that will need explanation from an instructor.

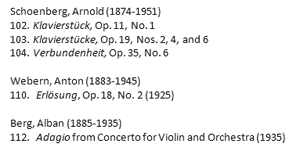

Example 3. Compositions in AAP by Schoenberg, Webern, and Berg

(click to enlarge)

[12] Works by the Second Viennese composers (Example 3) are less extensive and include six short pieces and the last section of Alban Berg’s

Concerto for Violin and Orchestra. The author identifies Nos. 104, 110, and 112 as serial compositions; other serial works in the anthology are by Krenek, Babbitt, and Boulez (although the last two are hardly within the technical range of most beginning undergraduate students). Besides wrong notes (particularly in Schoenberg’s op. 11, no. 1), these examples illustrate another problem in AAP. There is often no clear indication when a part is written in transposition (as, for example, the Alto Saxophone in

[13] The resetting of the Berg score is particularly curious. Although Bribitzer-Stull mentions the Bach chorale “Es ist genug” as related to the end of Berg’s twelve-tone row (not given), the score as printed completely eliminates Berg’s inclusion of the chorale text throughout the theme of the Adagio. Also missing are Berg’s markings of

Hauptstimme, Nebenstimme, and Choralmelodie and his indications of breath marks (as in the opening solo violin line, matching the words of the chorale). Surely these are important performance indications that directly affect analysis. The score is given at concert pitch (although the first two clarinets indicate clarinet in

[14] Bribitzer-Stull provides a wide variety of works for the classroom, with many accessible works (such as Mozart’s Ave Verum Corpus, a good example of chromatic chords and modulations) and a considerable number of complete twentieth-century works (such as George Crumb’s Black Angels). The bulkiness of the volume, however, makes it difficult to consider carrying to class every day. Any user should check every score for accuracy and should compare other available editions for markings which have been added or omitted in AAP. A teacher may decide on balance to access the many available public domain scores, and to concentrate on analyzing compositions suggested by class members from their current repertoire. Bribitzer-Stull reminds us to broaden the focus of the music theory core curriculum to include genres we often forget. Still, it is reassuring that he, just as Burkhart did in 1964, includes the first movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata op. 53 and Brahms’s Intermezzo op. 118, no. 2. Some compositions are too aesthetically rewarding and structurally fascinating to ignore.

Mary Wennerstrom

Indiana University

Jacobs School of Music

1201 E. Third St.

Bloomington, IN 47405

wennerst@indiana.edu

Works Cited

Lester, Joel. 1999. Bach’s Works for Solo Violin: Style, Structure, and Performance. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Selected anthologies/editions published since 2003

Selected anthologies/editions published since 2003

Benjamin, Thomas, Michael Horvit, Robert Nelson. 2010. Music for Analysis: Examples from the Common Practice Period and the Twentieth Century. 7th ed. New York: Oxford University Press. Excerpts arranged harmonically; also complete pieces and model analyses. CD.

Briscoe, James R. 2004. New Historical Anthology of Music by Women. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. With 3 CDs. Chronological from ancient Greece to late twentieth century. Biographical and critical essays.

Burkhart, Charles and William Rothstein. 2012. Anthology for Musical Analysis. 7th ed. Belmont: Schirmer/Cengage. With 7 CDs. Arranged chronologically from Plainchant through Beyond Modernism (late twentieth century).

Clendinning, Jane P. and Elizabeth West Marvin. 2011. The Musician’s Guide to Theory and Analysis. Accompanying anthology. 2nd ed. New York: W.W. Norton. 3 CDs. Arranged alphabetically by composer (from c. 1700 to twentieth century).

Kostka, Stefan and Roger Graybill. 2004. Anthology of Music for Analysis. Upper Saddle River: Pearson/Prentice Hall. Compositions from late seventeenth century to late twentieth century. Arranged chronologically.

Roig-Francolí, Miguel. 2008. Anthology of Post-Tonal Music. Boston: McGraw-Hill. Accompanies Understanding Post-Tonal Music. Anthology matches the chapter ordering of the text (roughly chronological from Debussy c. 1900 to Saariaho 2000).

Footnotes

1. Actually the Heiden example is the complete Diversion, and not just the Moderato section.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2013 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason, Managing Editor

Number of visits: