MTO at the Leading Edge

Eric J. Isaacson

KEYWORDS: Music Theory Online, technology

Copyright © 2014 Society for Music Theory

[1] As I sit with my feet propped up on my desk, typing on a wireless keyboard on my lap, a laptop computer and 23-inch monitor ahead of me, an iPhone recharging to the left, an iPad synchronizing to the right, and music streaming from Pandora quietly playing on Bluetooth-connected speakers across the room, it’s hard to picture how the technological landscape looked when the email announcing the first issue of MTO arrived twenty-one years ago. Many people didn’t have home computers yet. Some didn’t even have office computers. Windows 3.0, the first widely distributed version of that operating system, had been released less than three years earlier (May 1990). Email, stored on mainframe computers and accessed through terminal applications, was purely text-based—displayed in fixed-width fonts without modern adornments like italics. In contrast to today’s “always on” networks, going online from home required use of a dialup modem that tied up the household landline (cell phones were quite rare). Hypertext was in its infancy. Among the myriad things that grew out of this primordial Internet soup was a little scholarly journal that was bold in its conception and that effectively navigated the rapid, almost continual, changes in its technological environment. The first issue of MTO predated the establishment of the WWW Consortium and the founding of Mosaic (whose Netscape Navigator became the first broadly distributed web browser) by a year, and the incorporation of Google by five years. Unlike Netscape, Alta Vista, MySpace, KaZaa, and countless other early entrants to the Web, it has weathered the changes in technology, adapted to the times, and grown in relevance to its constituency.

[2] This article will survey MTO ’s twenty-one-year technological history.(1) My primary focus will be on the technologies that have come and—in some cases—gone over these two decades. I will start, however, with a look at how the journal has grown in other ways.

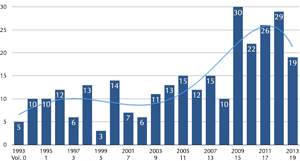

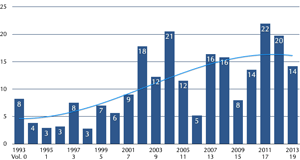

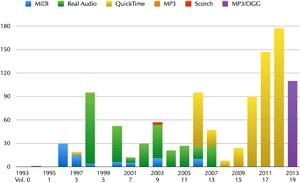

Figure 1. Number of articles published per year

(click to enlarge)

[3] At first, MTO’s normal publication pattern was to publish an issue when an article was ready for publication, to which would be added whatever reviews and announcements had been received at that point. The number of issues per volume thus varied in the early years, from four to as many as seven. Beginning in volume 8 (2002), however, the number remained steady at four issues per year. (One exception is that volume 15 [2009] had five numbers; nos. 3 and 4 formed a double issue, however, so there were in fact four issues that year, as well.) Although the number of issues per year has been steady, the number articles published per year has been increasing over time (Figure 1).(2) In volumes 0 (1993) through 8 (2002), MTO averaged one to two articles per issue. From volumes 9 through 14 (2003–08) the average jumped to 3–4. Beginning with volume 15 (2009), the average has been closer to six articles per issue. The number of articles often jumps in years when an issue has a special collection of articles. For instance, volume 6 included two such issues, one (no. 1) included five articles taken from the 1999 SMT plenary session, while another (no. 3) featured six articles derived from the plenary session of the 2000 Meeting of the New England Conference of Music Theorists. Volume 15, nos. 3–4 contained 15 essays on disabilities.

[4] What has not changed in a consistent way is the length of the articles published in MTO. During the first three years (volumes 0–1, 1993–95) the average article included about 22 paragraphs,(3) and in fact, if we exclude a 130-paragraph piece in volume 2, no. 6, the same is true of volume 2 (1996). After that, the articles in most volumes average 30–40 paragraphs, ranging from 26 in volume 6 (2000) to 47 in volume 8 (2002).

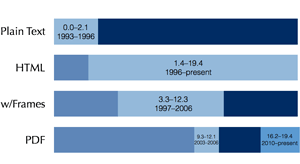

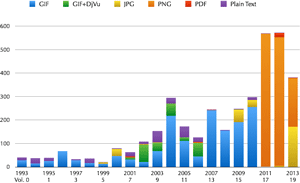

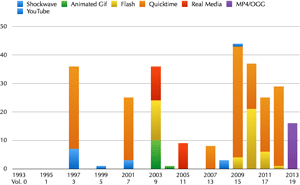

Figure 2. Publication formats

(click to enlarge)

[5] Figure 2 shows the formats in which MTO articles have been published. Of course, in the first three years, MTO was distributed via an email listserv, though these early volumes were subsequently retrofitted to the web. The first item to appear in HTML came in William Rothstein’s Commentary on an article by John Rothgeb in volume 1, no. 3, though the first article formatted in HTML, by David Løberg Code, did not appear until the following issue. It wasn’t until volume 2, no. 2, that an entire issue was provided in HTML. In 1997, HTML began supporting framesets, which made it possible to lock different areas of the screen and scroll them independently; MTO jumped right on the technology in volume 3, no. 4, as it made it possible to put links to figures in one frame, footnotes in another, and the body of the text in another. Articles were available in frames for ten years, by which time they had gone out of vogue on the web.

[6] The PDF format has also been used. It made its first appearance in an article by John Roeder in volume 7, no. 1 (2001), in which five examples were rendered in PDF. In volumes 9–12 (2003–2006) two articles per year were published in PDF instead of HTML (including this one by Richard Cohn) because they featured extensive mathematical equations that were deemed too difficult to render in HTML at the time. As HTML became more sophisticated, these equations could either be rendered as individual graphics and embedded inline or rendered directly in HTML and publication of articles in PDF ceased. Since volume 17 (2011), however, all articles have included a link to a PDF version, which makes them easier to print (and, presumably, to include in dossiers for tenure and promotion).

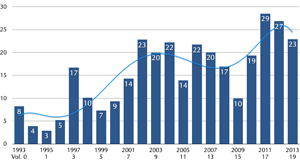

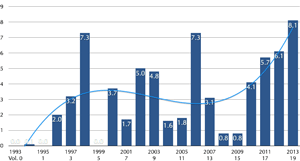

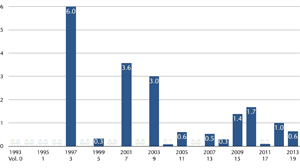

Figure 3. Total captioned items per article, per year

(click to enlarge)

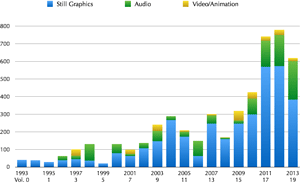

Figure 4. Total captioned items per year, by category

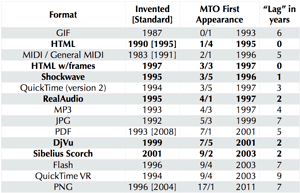

(click to enlarge)

[7] One of the great promises of the web was the ability, not just to link word and image as in traditional print media, but to include media in other formats, such as sound, animation, video, and even interactive elements. As it became easier to create media, the use of these media in MTO increased dramatically.

Figure 3 shows the average number of captioned items, e.g., figures, musical examples, and tables, appearing per article each

[8] Combine a dramatic increase in the number of articles with a dramatic increase in the number of captioned items per article and the growth rate becomes exponential. Figure 4 provides this picture, distinguishing between still images, audio files, and moving images. Still images have been present since the very first article in volume 0 (by David Neumeyer). We can see that audio files have been a consistent feature since first appearing in vol. 2 (1996). Animation and, more recently, video have grown increasingly common, appearing at least once a year beginning with volume 13 (2007). While more and longer articles contribute to this growth, more significant are improved and more accessible tools for the creation of media in various formats and their mastery by a growing segment of the submitting population. We will examine these three categories—still images, audio, and video/animation—in more detail in the paragraphs that follow.

Figure 5. Average number of still images per article, per year

(click to enlarge)

Figure 6. Total still images used per year, by file format

(click to enlarge)

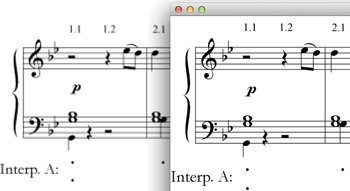

Figure 7. GIF (left) and DjV (right) versions of a musical example, in both cases scaled to 200%. Taken from Example 3 in Dodson 2002

(click to enlarge)

[9] By still images I mean those captioned items that neither move nor make sound. Figure 5 tells a story similar to that one above, one of growth over time in the number of items per article, an over-three-fold increase from the first years to the most recent. There are considerable variations from one year to the next, resulting from individually extreme articles (e.g., Walter Everett’s article in volume 10, no. 4 [2004], includes 83 captioned images, the most of any article to that point, and is the chief contributor to the spike in figures that year).

[10] Figure 6 provides the total number of still images used each year, now categorized by file format. As we explore this in detail, we can learn some things about the development of technology—and some related cautionary tales. Through volume 16 (2010), the predominant file format used for still images was GIF. Developed in 1987, it was a natural first file format to use. The GIF format is lossless, meaning that every pixel is preserved, but it also uses a compression formula to represent images very compactly. This was especially important in the early days of MTO when most people connecting to the Internet from home were using modems over a phone line that would download data at a maximum of 28.8 kilobits per second, the state of the art in 1994. (For comparison: a 10 megabyte file that today will download via a standard home cable modem in 3–4 seconds would have taken about 45 minutes to download using a 28.8k modem.)

[11] Early GIF images were produced by monochrome scans or screenshots from low-resolution monochrome monitors. This gave them a pixelated appearance that was inferior to print. Beginning in 2001, MTO produced musical examples in both GIF and a new format called DjVu, which was capable of producing smoother-looking graphics that would scale more gracefully, rendering musical examples more visually attractive. Figure 7 demonstrates DjVu’s superiority in over GIF in a 2002 MTO article. Unfortunately, DjVu was never adopted as a standard and, perhaps as a result, was never supported natively by web browsers. Meanwhile, improvements in both scanning technology and graphics software improved the quality of GIF images and use of the DjVu format in MTO was thus discontinued with volume 13 (2007), following a six-year run. Fortunately, no examples were provided solely in DjVu format, so those articles that use it—it was used in 19 issues—can still be read without additional effort on the part of the reader. Although the links within MTO articles to DjVu plugins are currently broken, viewers for DjVu images are still available for those moved to expend the extra effort.(5) We can, however, consider this our first instance of functional obsolescence.

[12] With volume 17 (2011), the superior PNG format replaced GIF as the default for graphical examples. Among other formats, a small number of complex figures have been offered in PDF format. Relatively few items have appeared using JPG, which, as a “lossy” format, is better suited for photos and less effective in settings, like those involving music notation, that involve angled lines and sharp edges. Finally, numerous captioned items ranging from tables to timelines to lyrics could be represented as plain text and these can be found throughout MTO’s history, including this example by Alan Dodson. Nevertheless, in many instances, particularly where the layout is sensitive, authors have prepared text-based figures in another program and then exported them as a graphic file (GIF or other).

Figure 8. Average number of audio files per article, per year

(click to enlarge)

Figure 9. Total audio files used per year, by file format

(click to enlarge)

[13] Among the great promises of MTO was the ability to include audio and moving images. Figure 8 shows that audio files have been a regular feature to varying degrees since volume 2 (1996). Over the first fifteen years or so, the average article included three audio examples, though there were years with fewer, balanced by a small number of audio-intensive articles in volumes 4 (1998) and 12 (2006). Beginning with volume 16 (2010) nearly every score example, regardless of length, had a corresponding audio file, which is of course the way it should be.

[14] Figure 9 breaks down the number of audio files used each year by file type. Here we find more dramatic evidence of the effects of technology changes in an online journal. In the early years, MIDI files provided a compact way to provide simple musical examples. Unfortunately, in another instance of functional obsolescence, web browsers have not supported MIDI for many years. The last use of MIDI in MTO was in volume 12 (2006). In any case, digital audio is generally superior to MIDI for the applications found in MTO. We take streaming audio for granted now, but it seemed magical in the mid-90s. Unfortunately, it was also not standardized. Two systems in particular were emerging at the time—Apple’s QuickTime and RealAudio. RealAudio had certain advantages over QuickTime for MTO at the time—it was easier to deliver from our server and it wasn’t clear that QuickTime was going to be free to end users—so RealAudio became the format of choice in MTO for a decade from volume 4 (1998) to volume 13 (2007). In the meantime, however, QuickTime became the industry standard, while RealAudio receded into obscurity. Over the course of volumes 12 and 13 (2006–07), MTO converted, and from volumes 14 through 18 (2008–12), Quicktime was used exclusively for audio files in MTO. Beginning with volume 19 (2013), audio has been provided in both MP3 and OGG Vorbis formats, with a new HTML5-based media player provided.

Figure 10. Average number of animation/video files per article, per year

(click to enlarge)

Figure 11. Total video/animation files used per year, by file format

(click to enlarge)

Figure 12. Technology adoption

(click to enlarge)

[15] Even more exciting than still images is the possibility of moving images, whether animated graphics or actual video. Figure 10 shows the average number of captioned animated or video items per article, per year. The use of moving images has clearly been less regular than other formats, as their use is the exception rather than norm. We see clusters in volumes 3 (1997), 7 (2001), and 9 (2003) resulting from extensive use in one or two articles. The record for a single article is still held by Brinkman and Marvin for an article in volume 3 (1997) that included a total of 36 animations.

[16] The overall use of video and animation has increased considerably since volume 15 (2009). This can be seen in Figure 11, which shows the file formats used for animation or video in MTO. The first moving images in MTO appeared in volume 3 (1997), using Shockwave and QuickTime video. This was just two years after the Shockwave browser plugin was first available and three-years after the introduction of QuickTime 2.0, the first version to support both Macintosh and Windows platforms. Articles in volumes 9 (2003) and 11 (2005) included video using RealMedia player, while articles in volumes 9 (2003) and 10 (2004) included animated GIFs. Flash made its first appearance in volume 9 (2003) as well, and was used multiple times in volumes 15–18 (2009–12). In volume 19 (2013), MTO switched to support multiple file formats for each image, including MP4 and Ogg Vorbis.

[17] Since its inception, Music Theory Online has been at the forefront of online scholarship. In the wild-and-wooly world of the early Internet, as new capabilities emerged, they could often be found quickly in MTO. These are summarized in Figure 12. This figure requires multiple asterisks, particularly in the second column, which indicates the year each format was “invented” and when it was adopted as a standard by some body. Invention dates are hard to pin down and, in any case, are of varying meaning, since the lag time between invention and widespread use is measured in months in some cases, but years in others. Likewise, while approval of a “standard” form of a format imputes a certain cachet, it does not necessarily signal its availability or suitability in a special way. Nevertheless, we can glean some highlights from this information. While the first specifications for HTML were developed in 1990, the first standard wasn’t adopted until 1995—the very year it was first used for MTO (volume 1, number 4). Support for frames was introduced in 1997, and they appeared in MTO that same year (volume 3, number 3). Shockwave, the browser plugin to play animation developed in Macromedia Director, was released in 1995, and was used in MTO already in 1996 (volume 3, number 5). When audio and video were needed, the two-year-old RealAudio and three-year-old QuickTime were ready. Meeting the desire for higher-quality graphics, DjVu (created 1999, first used in 2001) provided a solution. And the only use of the Scorch format in MTO, used to display music notation files created with Sibelius, appeared within two years of the release of that format.

[18] The flipside of rapid adoption is the risk of obsolescence, as I alluded to earlier. As new technologies emerge and supplant established ones, or as one technology emerges from a field of competitors, some technologies inevitably find themselves in the scrap heap of history. Three technologies fall into this category for MTO. While all of these media can still be played, doing so requires some effort, and they can therefore be considered functionally obsolescent. The affected technologies are RealAudio and RealVideo, which involve 22 and 2 issues, respectfully, spanning volumes 4 through 13 (1998–2007); DjVu, which affects 19 issues in volumes 8–12 (2002–6), and MIDI, which affects 11 issues in volumes 0–12 (1994–2006).

[19] Given that MTO was there at the start of the Internet, it is remarkable that things have gone as smoothly as they have. We cannot know what technologies will exist twenty more years in MTO’s future, nor can we know what technologies MTO has employed will cease to function. What seems beyond question, however, is that MTO will continue to be a thriving vehicle for the presentation of innovative scholarship.

Eric J. Isaacson

Indiana University Jacobs School of Music

1201 E Third Street

Bloomington, IN 47405.

isaacso@indiana.edu

Works Cited

Code, David Løberg. 1995. “Listening for Schubert’s ‘Doppelgängers’.” Music Theory Online 1, no. 4.

Dodson, Alan. 2002. “Performance and Hypermetric Transformation: An Extension of the Lerdahl-Jackendoff Theory.” Music Theory Online 8, no. 1.

Gauldin, Robert. 2004. “Tragic Love and Musical Memory.” Music Theory Online 10, no. 4.

Footnotes

1. Though we celebrate the start of volume 20 with this issue, this is actually year 22 of the journal, as the provisional volume 0 spanned two years (1993–94). In the figures that accompany this summary, I will treat the volume 0 years separately.

Return to text

2. I am counting as articles items labeled “Target Article” (a term used through volume 4, no. 5), “Article,” and “Essay.” I am omitting 66 items labeled “Commentary,” though some of these are longer than some of the articles and some also include multimedia elements. I am also omitting 132 “Reviews.”

In this and several other figures, I have added a trendline that smoothens the inevitable year-to-year variations. Several trendline formulas are available and I’ve tried to choose the one in each case that seems to me to most accurately tell the “story. ”

Return to text

3. The paragraph is of course a crude measure of length as authors have different styles where paragraph construction is concerned. Since MTO paragraphs are numbered, however, they are easy to count and one can assume that, over a number of articles, these things tend to normalize a bit.

Return to text

4. Counting captioned items is tricky in some cases and resists methodological consistency. For the most part I have tried to count actual image files used. Some examples with a single caption contain multiple pages (e.g., three pages of score with individual links); in these cases each image was counted. Some images contain multiple examples or parts of examples (e.g., this single image from Code 1995 includes five captioned examples); such cases were counted as one. On the other hand, some multi-part examples contain a separate graphic image for each part (here is an extreme example from Gauldin 2004); in these cases each image file was counted separately. Where two versions of the same graphic or audio file were offered, I counted this only once, however. Increasingly, mathematical formulas are being simply embedded as graphics in the text without captions; I have not counted these. Had I done so, figures for recent volumes would have been considerably higher.

Return to text

5. See http://djvu.org/ for links.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2014 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Carmel Raz, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

10916