Unpacking the Box in Frescobaldi’s Ricercari of 1615

Massimiliano Guido and Peter Schubert

KEYWORDS: ricercare, keyboard improvisation, counterpoint, pedagogy, Frescobaldi, Diruta, Banchieri, Burmeister, Sancta Maria

Copyright © 2014 Society for Music Theory

Introduction

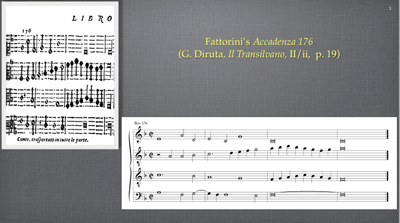

[1] “Unpacking the box” means first composing a four-part progression and then extracting voices to be sounded imitatively. The first explicit appearance of the concept is in Burmeister (1606). Our presentation focuses on a collection of “cadences” included by Diruta in Il Transilvano (1609). These cadences repay close study, for they show how a progression can contain contrapuntal ideas of a high degree of sophistication: the four voices provide all the material needed for making a point of imitation, with several lines in invertible counterpoint and imitation. Diruta’s schemata constitute only a first step for learning this technique through improvisation. Examples from Frescobaldi’s music reveal how he might have used this didactic method as a basis for a ricercar. However, a skilled composer such as he was would go far beyond Diruta, recombining themes at different time intervals, varying melodies through inganno and other techniques.

[2] Diruta’s examples provide a set of refined compositional tools, with almost no verbal explanation. The young organ student would have had to spend many hours of practice on these cadences to remember the four melodies, to be able to recombine them in their various transpositions, and to shorten them if needed. In other words, the student would have to feel comfortable handling the “box.” Our presentation recreates a learning session, with the maestro explaining the art of counterpoint and his student realizing it at the keyboard.

[3] The instrument heard in this video is an important musical personality in its own right. It was built in Italy during the seventeenth century by an anonymous maker and bears the signature “F.A. 1677” on its lowest key. Typical of many Italian harpsichords of the time of Frescobaldi, the keyboard has a range of four octaves (short octave C/E to c''') and the instrument has two 8-foot registers. It is not known where it passed the 17th and 18th centuries, but at some point it crossed the Atlantic. It was found in an antique shop in Cambridge Mass. in the early 1950s, by Frank Hubbard and William Dowd (then partners) who restored it in their newly founded shop there. Frank Hubbard made drawings of it during the restoration which served as Plates I through III of his ground-breaking book, Three Centuries of Harpsichord Making (Hubbard 1965). It was acquired by Kenneth Gilbert in 1965 and spent some years in Montreal before going to Europe where it was housed in Chartres Museum; it was used many times during its tenure there for commercial recordings. Legend has it that it once belonged to James McNeill Whistler, who painted it several times, once with his famous Mother; there are also the Whistler dragonflies on the outer case. It has just recently arrived at McGill as part of the Kenneth Gilbert Harpsichord Collection. Hearing Frescobaldi’s music on a contemporary artifact tuned in quarter comma meantone temperament is about as close as we can get to hearing a recording made in the 17th century–it opens a window on a long-lost and fascinating soundscape. The instrument and this short history are courtesy of Kenneth Gilbert.

Dialogue, Day 1

(click to watch the video)

Dialogue, Day 2

(click to watch the video)

Dialogue, Day 3

(click to watch the video)

Slides (PDF file)

Massimiliano Guido

Schulich School of Music

McGill University

555 Sherbrooke St. W

H3A 1E3 Montreal, QC

Canada

massimiliano.guido@mail.mcgill.ca

Peter Schubert

Schulich School of Music

McGill University

555 Sherbrooke St. W

H3A 1E3 Montreal, QC

Canada

peter.schubert@mcgill.ca

Works Cited

Primary Sources

Primary Sources

Banchieri, Adriano. 1983 [1614]. Cartella musicale. Bologna: Forni.

Burmeister, Joachim. 1993 [1606]. Musical Poetics. Translated, with Introduction and Notes, by Benito V. Rivera. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

de Sancta Maria, Thomas. 1991 [1565]. The Art of Playing the Fantasia, 1565. Translated by Almonte C. Howell, Jr. and Warren E. Hultberg. Pittsburgh: Latin American Literary Review Press.

Diruta, Girolamo. 1997 [1593, 1609]. Il Transilvano. Bologna: Forni.

Frescobaldi, Girolamo. 2005 [1615] Recercari et canzoni franzese fatte sopra diversi oblighi in partitura : Libro primo (1615). Edited by Gustav Leonhardt. Vol. 9, Monumenti musicali italiani, 24. Milano: Suvini e Zerboni. Facsimile ed. Farnborough: Gregg Press, 1967.

Zarlino, Gioseffo. 1965 [1558]. Le institutioni harmoniche. Facs. New York: Broude Bros.

Secondary Sources

Secondary Sources

Guido, Massimiliano. 2012a. “Counterpoint in the fingers. A Practical approach to Girolamo Diruta’s Breve & Facile Regola di Contrappunto.” PhilomusicaOnline 11, no. 1: 63–76.

—————. 2012b. “Rethinking Counterpoint through Improvisation. A Multidisciplinary Conversation with Edoardo Bellotti, Michele Chiaramida, Michael Dodds, Andreas Schiltknecht, Peter Schubert, and Nicola Straffelini.” PhilomusicaOnline 11, no. 1: 5-9.

—————. 2013. ”‘Con questa sicura strada:’ Girolamo Diruta’s and Adriano Banchieri’s Instructions on How to Improvise Versets.” The Organ Yearbook 42: 40–52.

Hubbard, Frank. 1965. Three Centuries of Harpsichord Making. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press: Plates I–III.

Schubert, Peter. 2002. “Counterpoint Pedagogy in the Renaissance.” The Cambridge History of Western Music Theory. Edited by Thomas Christensen. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 503–33.

—————. 2006. Baroque Counterpoint with Christoph Neidhöfer, Upper Saddle River, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

—————. 2007a. “Hidden Forms in Palestrina’s First Book of Four-Voice Motets.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 60, no.3: 483–556.

—————. 2007b. Modal Counterpoint, Renaissance Style. New York: Oxford University Press, 2nd edition.

—————. 2012. “From Voice to Keyboard: Improvised Techniques in the Renaissance.” Philomusica on-line 11, no. 1: 11-22.

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2014 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Michael McClimon, Editorial assistant

Number of visits:

25070