Review of Virtual Library of Musicology (ViFaMusik), (http://www.vifamusik.de)

Henry Hope

KEYWORDS: research tools, digital humanities

Copyright © 2014 Society for Music Theory

[1] Before the advent of computers, the internet, and cheap travel, many music historians made a name for themselves by discovering previously unknown materials and making them available to the wider scholarly community for the first time. Profiting from a rapid increase in the availability of information, both historians and theorists of the twenty-first century are faced with a different, but equally great challenge: even though currently unknown research objects undoubtedly continue to remain hidden from sight, one of the crucial tasks of scholars today is to establish ways of managing and querying the expanse of information. Nowadays, scholars are obliged less to find new materials than to make sure not to miss those already available. As academics, we are called to have in view our research fields in their entirety, yet with the ever-growing number of new music theorists entering the discipline, the attempt to keep track of the wealth of new publications and resources demands more and more time and attention from scholars. Though enabling a plethora of new research and constituting valuable contributions to musicology in themselves, online publications, editions, and databases often prove particularly elusive: gone are the days when keeping a watchful eye on the new acquisitions shelf in the library would have ensured that one was aware of the world of music theory at large.

Figure 1. ViFaMusik English start-up page

(click to enlarge)

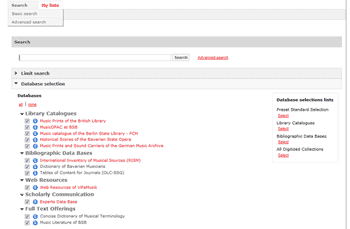

Figure 2. ViFaMusik’s search function

(click to enlarge)

[2] Jointly hosted by the Gesellschaft für Musikforschung (GfM), the Staatliches Institut für Musikforschung Preußischer Kulturbesitz (SIM), and the Bayerische Staatsbibliothek (BSB), and supported by funds from the Deutsche Forschungsgesellschaft (DFG), the Virtuelle Fachbibliothek Musikwissenschaft (ViFaMusik) has been set up to make this seemingly impenetrable wilderness of musicological research accessible. Available online at www.vifamusik.de, the project ambitiously describes itself as “the central portal for music and musicology, [which] allows you to access an extensive digital library containing the latest scholarly research and online resources. Using a single search engine you can find bibliographical data, full text data, and information about experts in musicology.” Though designed in German, the website is also available in English (http://www.vifamusik.de/home.html?L=1, or by clicking on the “English” link at the top right; see Figure 1).

[3] The centrepiece of ViFaMusik is its sophisticated ‘meta’-search-engine, which enables a simultaneous query across multiple catalogues, each of which can be selected or deselected to fit the user’s needs (see Figure 2). The list of included resources is extensive. The library catalogues included are the catalogue of printed music at the British Library (BL), the catalogues of music literature at the BSB and at the Staatsbibliothek Preußischer Kulturbesitz in Berlin (SBPK), the catalogue of historical performance materials at the Bayerische Staatsoper in Munich, as well as prints and sound recordings at the Deutsches Musikarchiv (DM). Further bibliographic information is obtained through the Répertoire International des Sources Musicales (RISM), the online encyclopaedia of Bavarian musicians, and a pool of content-listings from selected journals. The search also encompasses the website’s own materials as well as ViFaMusik’s catalogue of researchers. Finally, it also allows a full-text search of the Handwörterbuch der musikalischen Terminologie (HmT), and the literature fully digitised by the BSB. The advanced search further allows users to refine their query by exact or approximate title, author, keyword, year (also year-range), and ISBN.

Figure 3. ViFaMusik’s search results with built-in WorldCat function

(click to enlarge)

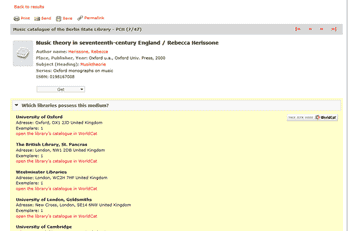

[4] A title-term query for “music theory” dated between 2000 and 2014 across all available catalogues and databases, for example, renders a wide range of results: 178 entries in the catalogue of the BSB, 5 among the prints at the BL, 4 at the DM, 47 at the SBPK, and 127 in the database of journal articles. In some cases, the search results can be accessed through WorldCat, allowing users to find the copy of a given item in their local library (as long as the library is part of the WorldCat project). Clicking on the WorldCat link for Rebecca Herrisone’s monograph Music Theory in Seventeenth-Century England, for example, reveals that there is a copy close to my current location, at the Bodleian Library in Oxford (see Figure 3). Unfortunately, this function is not available for all search results. Likewise, the feature of linking users through to articles that are openly available online is also not yet fully functional: when trying to access Jeff Perry’s 2007 article “Music Theory as Conversation” in Music Theory Online (MTO), users are redirected to an interstitial page (in German), which forwards them to MTO’s generic start page, rather than Perry’s article.

[5] Of particular value to music theorists is the range of journals indexed and searchable through ViFaMusik, as these include not only specific theory journals such as the Journal of Music Theory, Music Analysis, and Music Theory Spectrum, but also non-subject specific journals which may nonetheless include relevant publications. A search for the term “Riemann” in the titles in the issues of these 153 content-searchable journals that were published since the great music theorist’s 150th anniversary in 1999 yields not only a number of reviews of recent monographs on Riemann’s legacy, but also lists two articles by Kevin Mooney (Journal of Music Theory) and one by Alexander Rehding (Music Theory Spectrum) as well as an article by Elmar Seidel (in German) on Riemann’s understanding of Anton Bruckner’s Te Deum, published in the more obscure Kirchenmusikalisches Jahrbuch, which music theorists are unlikely to have encountered otherwise, since this journal is not searchable by other tools such as JSTOR.

Figure 4. Immediate access to Türk’s discussion of “Trugschluss” through ViFaMusik

(click to enlarge)

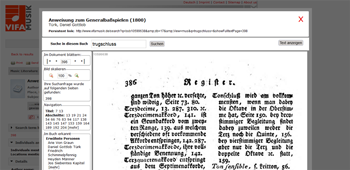

[6] Equally usefully, the search engine enables queries of the Bavarian State Library’s fully digitized music publications of the nineteenth century, which include a wide range of invaluable theory treatises. Searching this resource for the term “Trugschluss” (deceptive cadence), for example, produces a stunning 190 results, ranging from Daniel Gottlob Türk’s instruction in continuo playing of 1800 (“Anweisung zum Generalbaßspielen”; see Figure 4) to Christian Heinrich Hohmann’s 1870 study guide to musical composition (“Lehrbuch der musikalischen Composition”). From ViFaMusik, users can access the queried term in any of these texts by a simple click on the button “Read online.”

[7] ViFaMusik also features a number of other useful heuristic tools: via the start page, users can access a list of music-related journals, which are ordered by their sub-discipline. The site also provides links to a wealth of databases and other sites of musical interest: in addition to the library catalogues and full-text databases available in the search-engine, these links include the Répertoire International d’Iconographie Musicale (RIdIM), biographical resources, manuscript collections, and libretti. Audio and audio-visual projects are also catalogued on ViFaMusik. In addition, the website hosts digitized versions of research dissertations and conference proceedings. It currently features a sub-site on World Music, which is, however, not yet available in English. This sub-site brings together relevant literature and information for researchers and students in this particular area of research. The number of such sub-sites is supposed to be expanded in the future.

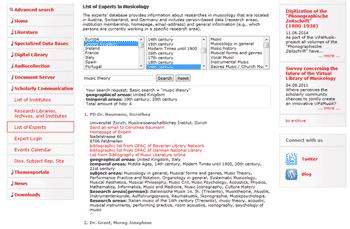

Figure 5. Search results from “List of Experts”

(click to enlarge)

[8] Especially noteworthy is the website’s category with the slightly cumbersome heading “scholarly communication.” These pages list institutions of musical study and link to an overview of music archives/libraries in the German-speaking countries hosted by the Deutsches Musikinformationszentrum in Bonn. Both are particularly useful to researchers from outside these countries, pooling information and facilitating initial stages of research and contact by including contact addresses and links to the institutions’ web-pages. In addition, ViFaMusik provides its own database of music scholars. Academics can register with the site and note their institutional affiliations, research interests, and contact details. This information is fully searchable and allows scholars to seek out potential collaborators, or experts in a specific area who may be able to assist them with complex research questions. The database currently lists 955 music scholars from a range of countries and sub-disciplines: even a relatively specific search for scholars working on British music of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, with an interest in music theory, yields as many as four scholars employed in three different countries (see Figure 5): Dorothea Baumann (Switzerland), Morag J. Grant (Germany), J. P. E. Harper-Scott (UK), and Petra Weber-Bockholdt (Germany). Similarly rich is the amount of information that can be obtained from the database of doctoral theses to which ViFaMusik directs its users.

[9] In contrast to the rich pool of researchers and the wide spectrum of resources referenced on ViFaMusik, the “events calendar” is furnished rather poorly. Hosted, like the dissertation database, by the GfM, the site lists only a limited selection of upcoming conferences, and these are not searchable. In contrast to the meagre 30 conferences advertised on the GfM pages at the time of writing, the “Golden Pages” site hosted by J. P. E. Harper-Scott lists as many as 109 events and additionally provides direct links to other conference-listings (http://goldenpages.jpehs.co.uk/conferences/). More problematically, however, the link from the English ViFaMusik pages to the events listing on the GfM site is currently broken; the latter can be reached only from the German version of ViFaMusik.

Figure 6. ViFaMusik blog

(click to enlarge)

[10] The wordpress blog run by ViFaMusik (see Figure 6) provides updates on newly available online resources (http://vifamusik.wordpress.com/). The archive of blogposts reaches back to January 2011, and since then, new posts have been added almost every month. Users can subscribe to the blog or an RSS feed in order to be informed about new posts, and the website allows users to comment on blogposts and share them through twitter. The blog’s statistics suggest that its information is already reaching a large number of users: while the blog started off with 1,800 views in 2011, numbers strongly increased to 3,000 for 2012; the past year saw a slight decrease in usage to 2,500 views. Compared against the total of 955 researchers currently registered with ViFaMusik, however, these figures demonstrate the enormous potential that as yet remains unrealized. The most popular new post in 2013 was the information that the HmT was now available online: on the first day of its release, the post had 88 views—not even ten percent of the users registered with ViFaMusik. The project’s twitter account reveals a similar extent of unused potential: on twitter since January 2011, @ViFaMusik currently has 239 followers; the twitter account of the Digital Image Archive for Medieval Music (@diammpub), in contrast, has 366 followers although it went live at almost the same time (December 2010); within less than a year, @MTOJournal has managed to accumulate just under 100 followers. These figures suggest that an account such as @ViFaMusik—of interest to musicologists of all sub-disciplines, not just to medievalists or music theorists—should have a much larger following.

[11] The present review would like to suggest two ways in which ViFaMusik’s impact might be improved significantly in the future. First, the site would profit from being more consistently open to users without a strong proficiency in German. While the majority of German-speaking scholars are comfortable reading (and communicating) in English, many English-speakers sadly do not have sufficient language skills to read German. Since the blog and twitter accounts are presently German-based, they are inaccessible to many Anglophone scholars. The lacking English translations for some pages of ViFaMusik, alongside a number of cumbersome translations, broken or inconsistent links in the site’s English version, and lacking English keywords in the database’s search function add further barriers for potential Anglophone users. The blog’s statistics confirm this observation: of its 2,500 users in 2013, only 80 were based in the USA or the UK.

[12] Second, ViFaMusik’s current interface is overly complex and hides some of the site’s treasures from sight. A short video/guide to the website, for example, would help users to navigate the plethora of available resources. The distinction between “literature,” “spezialized data bases” (sic!), and “digital library” is not readily apparent, requiring users to browse around in order to find features of particular use to them. The orange/red color-scheme and the rather academic choice of font add to the generally uninviting appearance of the website.

[13] These suggestions notwithstanding, ViFaMusik constitutes a valuable research tool that enables scholars to retain an overview of the many digital resources already available to them. I would encourage anyone working in music to take an afternoon or two to explore the possibilities generated by ViFaMusik: this will certainly be time well-spent, for the site has the potential of improving the general awareness of research materials within musicology and music theory. The “work-in-progress” initiated by ViFaMusik is beginning to reap first fruits, and the promised continued expansion of the site’s features will render ViFaMusik an even more invaluable scholarly tool in the future.

Henry Hope

Madgalen College, University of Oxford

High St

Oxford

OX1 4AU

UNITED KINGDOM

henry.hope@music.ox.ac.uk

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2014 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Rebecca Flore, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

7716