From Me To You: Dynamic Discourse in Popular Music *

Matthew L. BaileyShea

KEYWORDS: persona, pronouns, distance, intimacy, narrative, popular music, point of view

ABSTRACT: Scholars have long recognized the complexities of song personas in popular music. Less well recognized is the way that the deployment of pronouns in pop song lyrics can create sudden shifts in the various currents of musical meaning. Although songs often commit to a single point of view, it is quite common for songs to feature complex shifts in discourse, sometimes aligned with important changes in the music. This paper addresses an especially important pattern, a shift from distance to intimacy.

Copyright © 2014 Society for Music Theory

[1] Johnny Cash’s 1963 recording of “Ring of Fire” begins with a short, provocative statement: “Love is a burning thing and it makes a fiery ring.” Although these could be the words of a distant, third-person narrator, it soon becomes clear that they are part of a first-person story: “Bound by wild desire, I fell into a ring of fire.” We also learn—in the second verse—that they are addressed to someone specific: “I fell for you like a child. Oh, but the fire went wild.” A distinct intimacy gradually emerges in the song’s lyrics. Even though the listener knows, in retrospect, that all of these words are addressed to the song persona’s lover, it takes time before that aspect of the song is fully unveiled.

[2] Similar examples abound. Percy Sledge begins his hit song “When a Man Loves a Woman” with seemingly distant ruminations about the troubles of men in love. But halfway through the song the lyrics shift into a far more intimate and expressive mode—“Well, this man loves you, woman”—and we quickly realize that the song persona is suffering under the same spell that he had been describing earlier from a distance. Unlike in “Ring of Fire,” the change to direct address is coordinated with a crucial shift in the music: it initiates a new formal section, a contrasting bridge, the song’s only deviation from the repetitive strophes of the preceding (and following) verses.

[3] The persona of Simon and Garfunkel’s “For Emily, Whenever I May Find Her” similarly delays the song’s eventual direct address, in this instance by recounting a dream of wandering alone down “empty streets” and “alley ways.” But the loneliness portrayed in these passages gives way to a more effusive, intimate expression with a sudden dynamic surge in guitar and vocals and a melodic leap to the song’s highest pitch: “And when you ran to me, your cheeks flushed with the night

[4] Scholars of popular music have long acknowledged the various complexities of song personas and narrative voice.(1) It is no secret that lyrics frequently involve changes in tone, character, and addressees, including both real and fictional audiences. As Simon Frith astutely observes, the question of “Who is singing to whom?” can be staggeringly complex (1996, 184). This complexity is often directly linked to the deployment of pronouns. David Brackett points out that Elvis Costello often uses pronoun shifters in a way that “creates a sense of multiple narrators or authorial voices” (2000, 194). Barbara Bradby’s seminal research on “girl group” discourse emphasizes the significance of various pronoun pairs, especially the way they position the persona as either subject or object: “active and passive pronoun sequences do not occur randomly, but can be correlated rather precisely with a structural opposition in the meaning of the songs between fantasy and reality” (1990, 350). Moreover, several scholars have shown how specific shifts in perspective can establish narrative complexity in lyrics and a corresponding change in the music. Nicholls suggests several connections between point of view and instrumentation in The Buggles’ “Video Killed the Radio Star” (2007, 303-7) and Negus shows how changes in perspective can affect narrative meaning in Steely Dan’s “Kid Charlemagne” (2012, 383).

[5] What I aim to show with this paper is that the specific movement that I’ve outlined in the songs above—a path from “distant” narration to more “intimate” discourse—is particularly important and deserves special scholarly attention.(2) It is a template that can guide us in our analysis and interpretation of countless songs. Manifestations of the pattern vary: in some cases, the movement towards intimacy is related to specific changes in the music—form, timbre, harmony, and so forth—while in others, it is an aspect of the lyrics alone. The effect on the song as a whole can range from trivial details to profound complexities. I begin by explaining how these shifts in discourse normally happen and conclude by looking at a number of specific examples.(3)

Everything in its Right Place

[6] For some readers, the idea that songs tend to move toward more intimate discourse will be intuitively obvious. Effusive emotional expression has always been a fundamental aspect of song. As Rosanna Warren writes, “after [the] early Greeks, the lyric cry rolls down the centuries, inflected differently in different eras and languages, but usually saying or pleading or insisting ‘I want’ and ‘I hurt’” (2008, 270). It is much less common, in other words, to encounter songs that tell us “he wants” or “she hurts.” As Alan Durant points out, the emphasis on “you” becomes especially prominent in rock music: “a density of second-person pronouns and imperatives . . . appears virtually without parallel in song-forms of any earlier periods” (1984, 203). Thus, if a song does begin from a somewhat distant vantage point, it is perhaps unsurprising that it would eventually move toward intimacy.

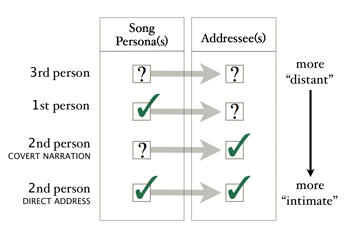

Example 1. Addresser/Addressee Relationships

(click to enlarge)

[7] Such movement directly relates to the way information is unveiled over the course of a song, especially with regard to two essential questions: Who is the song persona and who is being addressed? (See Example 1.)(4) In a consistent third-person narrative, such as Bob Dylan’s “Highway 61 Revisited,” there is no reference in the lyrics to the narrator, nor to any specific addressee. We might assume that Dylan’s song portrays an autobiographical narrator and every listener is an addressee, but nothing in the lyrics confirms those assumptions. Put simply, there is no distinct information about either side of the divide. If a verse were added that specifically acknowledged a narrator or addressee it would change the nature of the discourse.(5) Admittedly, the link between the real-life author and the narrator of a popular song is far more prominent than the link between the author and narrator in literary genres. When we read a third-person narrative by Henry James, we are unlikely to continuously imagine the autobiographical James as the narrator—indeed, in the absence of any unusual rhetorical shifts, a casual reader is unlikely to dwell on the nature of the narrator at all. But in “Highway 61 Revisited,” Dylan cannot simply disappear into the storyteller role; for most listeners, a familiarity with his voice and performance style will ensure that he remains an ever-present persona throughout the song. Nevertheless, the lack of any distinct lyrical “I” creates a sense of distance: Dylan’s song tells a story that the author appears not to participate in.(6)

[8] First-person narration adds a degree of intimacy, because it places the narrator into the song world as the central subject, but the target of the lyrics is left unacknowledged. When Mick Jagger sings, “I can’t get no satisfaction,” he takes on a persona that could be addressing a specific individual or a large group—maybe everyone who hears the song—but he doesn’t supply any information to clarify an intended audience. We have learned something about the song’s “I,” but nothing about a possible “you.” If he had added “Listen girl, I can’t get no satisfaction,” we would understand the song as a direct address to a particular individual rather than a general first-person narrative.

[9] The next two categories in Example 1 involve second-person address. The last of these, direct address, is the simplest: an addressee is specified and—especially in the case of songs about romantic love—the lyrics provide a clear sense of intimate expression from one person to another (e.g., “I want to hold your hand”). Both the song persona and the addressee are distinctly acknowledged. There is still a great deal that remains unknown about either individual, but the line of communication is clear.

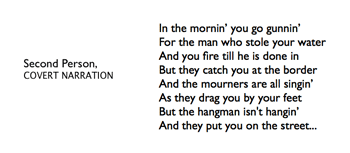

Example 2. Steely Dan, “Do It Again,” 1972

(click to enlarge)

[10] Direct address is by far the most common lyrical perspective and it doesn’t require a great deal of explanation. It should, however, be distinguished from what I refer to as “covert” second person, which focuses on the pronoun “you” but involves a hidden narrator, possibly in the mind of the song’s narrative subject, rather than a real, physical interlocutor. Example 2 shows the opening verse of Steely Dan’s “Do It Again,” which narrates the activities of a particular character using the pronoun “you.” In such cases, the second-person address is essentially a stand-in for what is, in effect, simply a more personalized version of third-person narration. Instead of a covert narrator telling about what happens to “him,” the narrator tells what happens to “you.”(7)

[11] Many songs consistently adopt one of these four perspectives from beginning to end. In an informal survey of the Rolling Stone top five hundred songs of all time (2011)—mostly classic rock songs—I found that nearly forty percent are consistently presented as second-person, direct address. Close to twenty percent are consistently sung from a first-person perspective. And only about one percent maintain third-person narration for an entire song (covert second person is exceptionally rare as a consistent mode of discourse for complete songs; it occurs somewhat more frequently in genres such as heavy metal, but it does not occur throughout any entire song on the Rolling Stone list). This leaves close to forty percent that shift modes of discourse at some point in the song. And of those songs, the shifts are almost always from a more “distant” perspective to a more “intimate” perspective.(8)

[12] As suggested above, this may be intuitively obvious simply because it is easier to add information about who is addressing whom than it is to take it away. The introduction of an addressee—whether an indefinite “you,” or a specific name such as “Ruby Tuesday” or “Peggy Sue”—conditions the audience to assume that subsequent lyrics are directed to that same person (even if it might be naïve to make such an assumption). Consider the case of Radiohead’s “Everything in its Right Place.” This song involves four lines of text sung consecutively. The first is an incomplete sentence: “Everything in its right place.” We don’t know who is singing to whom and there isn’t even a verb to clarify the utterance.(9) The next two lines introduce a first-person narrator: “Yesterday I woke up sucking a lemon,” and “There are two colours in my head.” But the song then moves on to second-person, direct address: “What was that you tried to say?” We thus have the gradual addition of the pronouns “I” and “you” in a way that shifts the song into a more intimate mode, and it does so just as the song becomes increasingly complex and frenetic, with significant metric displacements.

[13] These lines are somewhat Dadaistic and one could make a case that the ordering of the lyrics wouldn’t matter much in terms of the overall meaning of the song. But if the lyrics began with the question “What was that you tried to say?” it would condition us to hear the remaining text as additional direct address. In other words, the statement “There are two colours in my head” would likely be heard as an address to the same “you” from before, rather than interpreted as an isolated thought from a first-person narrator. The expressive shift that happens in the actual lyrics would be lost, from the “distant” opening statement to the final, desperate question asked of the song’s mysterious “you” (which some assume to be the digitally manipulated doppelgänger that appears in the background throughout the song [see Letts 2010, 227]).

[14] As already suggested, this type of motion toward direct address is extremely common. It reflects a long history of similar trajectories in lyric poetry. Shakespeare’s Sonnet 30 (Vendler 2002, 178) famously begins with a first-person narrator describing painful reminiscences:

When to the sessions of sweet silent thought

I summon up remembrance of things past,

I sigh the lack of many a thing I sought,

And with old woes new wail my dear time’s waste. . .

But the poem ends with a surprising turn toward direct address, an expressive move that completely overturns the loneliness and despair that inhabits the first twelve lines:

But if the while I think on thee, dear friend,

All losses are restored and sorrows end.

[15] The point I want to make, then, is that a shift in discourse toward greater intimacy is not only more likely to happen—by simply offering more information about who is communicating with whom—but also expressively significant.(10) Moving in the reverse direction—away from intimacy—is not impossible, but it is far less common. It requires, in effect, “erasing” previous assumptions about a song’s “I” or “you.” I will address several such examples below, but I first need to establish other crucial aspects of the movement towards intimacy, including two essential ways that shifts commonly occur.

Clarification vs. Substitution

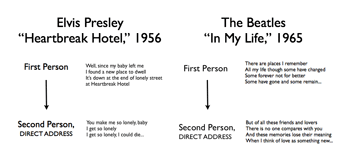

Example 3. a) Substitution in “Heartbreak Hotel,” Elvis Presley, 1956. b) Clarification in “In My Life,” The Beatles, 1965

(click to enlarge)

[16] Examples 3a–b present lyrics from two well-known songs: “Heartbreak Hotel” by Elvis Presley and “In My Life” by the Beatles. They both feature familiar shifts in discourse. In “Heartbreak Hotel,” the song’s persona initially addresses an unspecified audience, offering a first-person narrative about how his/her “baby” left. But the end of each verse switches to direct address: “You make me so lonely, baby. I get so lonely, I could die.” Quite obviously, there has been a substitution of addressee. The protagonist begins by addressing a person or group that presumably does not include his/her “baby,” but reserves the most urgent lament for the lover’s ears alone. This type of shift is extraordinarily common in popular music, often coinciding with formal divisions, frequently with verses in either third or first person and choruses with direct address.(11) Such songs move toward intimacy, but they repeat that cycle one or more times over the course of the song (assuming, as is typical, some number of alternations between verses and choruses).(12)

[17] “In My Life” also features a move toward more intimate discourse, but it does so in an entirely different fashion. The song begins with what appears to be a simple first-person narrative, but switches, after the first minute of music, to direct address: “But of all these friends and lovers, there is no one [who] compares with you.” Much like the Shakespeare sonnet above, we retrospectively understand that the entire text is addressed to a single person (this is true of all three examples in the introduction to this paper as well). But we still likely experience the moment—even if we’ve heard the song many times—as a dynamic and expressive shift. The abrupt change of focus forges an intimate bond between the singer and his lover. And it clarifies the overall mode of discourse rather than creating any substitutions.

[18] Conceptually, these categories are fairly simple, but there can be a great deal of ambiguity and complexity in the way songs invoke either possibility. Some singers adopt multiple roles over the course of a song—a substitution of the persona rather than the addressee—and we might find that possible moments of “clarification” aren’t actually very clear at all. This depends, of course, on the various inconsistencies and ambiguities in any given set of lyrics. Though it is relatively easy to locate specific shifts in discourse in songs such as “In My Life,” things aren’t quite so well defined in songs like “I Am the Walrus.”(13) Some lyrics simply resist easy classifications. In that sense, one might imagine a spectrum of complexity, where, on one side, are songs that consistently adopt a single mode of discourse (with direct address being the most common), and, on the other, songs that feature explicitly protean personas that frequently change roles and addressees (consider, for instance, Eminem’s “Without Me,” which mainly addresses a general audience, but often targets specific individuals and seems to involve both the ‘Marshall Mathers’ persona and the ‘Slim Shady’ persona).(14)

Narrative Theory and Popular Song

[19] My Example 1 uses fairly simple terminology that most readers, I suspect, will find easily understandable; the many complexities of narrative theory are, for the most part, unnecessary to support the basic argument that I’m advancing here. There are a few broad issues, however, that should be tackled before moving forward. Perhaps the most important has to do with the nature of “song personas” in most popular music. On the one hand, singers often adopt the role of storytellers, such as when Gordon Lightfoot sings about the wreck of the Edmund Fitzgerald. On the other hand, singers often engage in mimetic role-playing, where they essentially present a monologue—or one half of a “dialogue”—from a limited “scene.” This tends to happen in most love songs, where the singer addresses someone directly (e.g., “Earth Angel, will you be mine?”). But this distinction—between storyteller and role-player—actually becomes quite blurred in many cases. A song like “Johnny B. Goode” is mostly a third-person narrative about a country boy who plays guitar. In that sense, Chuck Berry takes on a clear role as “singer/storyteller.” But the choruses, “Go, Johnny go!” involve a brief bit of mimetic role-playing. They not only imply direct address from someone within the story (someone cheering on Johnny directly), but the guitar licks also suggest that Berry takes on the role of Johnny himself. Similarly, even a simple mimetic love song such as “Earth Angel” features a certain amount of narration, a story within the “scene” (“I fell for you and I knew . . . ”).

[20] This fluidity between roles raises the question of whether or not it would be wise to incorporate more sophisticated terminology into the model that I’ve presented above. H. Porter Abbott, for instance, suggests that Gerard Genette’s concept of “focalization” better captures the dynamics of most literary narratives than the standard use of “first person” or “third person” perspectives (2008, 75). But focalization—a term usually associated with a distinction between “who sees” and “who speaks” (Genette 1980, 186)—has itself been the source of a great deal of debate and confusion (see Nelles 1990 and Fludernik 2001). And although focalization has been a highly attractive concept for scholars of novels and films, nobody has yet made a strong case for its application to popular music. More relevant to this study, perhaps, is Genette’s concept of “narrative mood,” which explicitly addresses aspects of narrative “distance” (specifically, the degree to which the narrator is involved in the storytelling). These concepts have considerable potential—there are undoubtedly significant benefits to re-thinking the role of Genette’s ideas with regard to popular music—but they aren’t necessary to explain the general motion from “distance” to “intimacy” that I’ve outlined here.(15)

Dynamic Discourse and the “Double Address”

[21] In 1985, during the Live Aid concert at Wembley Stadium, Bono, U2’s lead singer, initiated what would become a notorious moment in his career. In the midst of the song “Bad,” he jumped off the stage, pulled a fifteen-year-old girl out of the crowd, and began slow-dancing with her as the band impatiently waited above, looping a simple two-chord progression. The moment resonated with many people because of the extraordinary contrast between the intimacy of their “private” moment against the sheer size of the audience (both the thousands in the stadium itself and the millions watching worldwide on television). This would become a common theatrical stunt for Bono and it is undoubtedly effective—and affective—partly because it is a natural extension of what already happens with many pop songs. Singers perform in front of an audience, but they often sing with an intimate direct address that imagines an isolated, private experience.(16)

[22] This paradox allows singer-songwriters to take advantage of the constant opportunity for what we might think of as a “double address”: the possibility of addressing both the imagined characters in a song’s fictional world and the real audience of listeners, whether in a concert hall or elsewhere. We might think of this as similar to “breaking the fourth wall” in stage drama, but the analogy doesn’t quite work given how comparatively smoothly song personas tend to move between the different types of address (nothing seems to be “broken” when this happens). Comparisons with poetic personas are, perhaps, more apt, but even then the degree of fluidity isn’t precisely the same. Put simply, pop music personas seem to be unique in the extraordinary ease and smoothness with which they can shuttle back and forth between these two types of address.

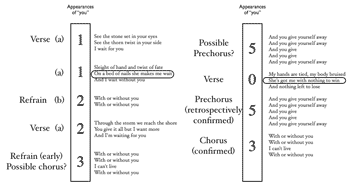

Example 4. U2, “With or Without You,” 1987

(click to enlarge)

[23] Consider U2’s “With or Without You,” which is fairly typical for the band in terms of its use of substitution (see Example 4).(17) The persona of this song, whether we think of him as Bono or some other fictional entity, primarily sings with second person, direct address: “See the stone set in your eyes / see the thorn twist in your side / I wait for you.” This, of course, is typical for songs about romantic love. But at two points in the song, he refers to his lover in the third person. We have, early on, the line, “on a bed of nails she makes me wait,” and later, “my hands are tied, my body bruised / she got me with nothing to win and nothing left to lose.”

[24] In the book Jokerman, Aidan Day discusses similar kinds of substitutions in various live recordings of Bob Dylan’s “Tangled Up In Blue” and seemingly suggests that it doesn’t necessarily matter that much: “it is all one to the soul,” he writes (1988, 65). We might feel the same about “With or Without You”; the song presents a suffering persona, laying bare his pain and torment in an obviously complicated relationship. This comes across whether the persona sings “she” or “you.” And we could certainly imagine performances of this song where these moments are kept consistent with the direct address of the rest of the song. The lyrics could easily become: “on a bed of nails you make me wait” and “you’ve got me with nothing to win.” If this happened during a live performance it’s hard to imagine that any but the most diehard fans would even notice the change.

[25] But this doesn’t mean that these pronoun shifts are unimportant. In fact, there are several ways in which the changes in perspective might be deemed significant. Perhaps the most obvious is that the song presents us with a persona who is suffering whether his lover is present or absent. The lyrics intensify that split by, on the one hand, featuring direct address, as if the woman is right there before him, but, on the other hand, referring to her twice in the third person. The discourse, in other words, reinforces the message.

[26] But the discourse also tilts the song more toward a sense of absence than presence. Is the lover present in this song at all? Despite all the use of direct address, the song not only slips twice into third person, but also includes the lines “I wait for you” and “I’m waiting for you.” This opens up the possibility that the song is an anguished cry within the psyche of the suffering persona. He’s addressing a mental image of her, but she isn’t there. This interpretation would be less convincing with consistent direct address, and would make the lines about waiting somewhat nonsensical.

[27] The pronoun shifts also reinforce the overall wave-like dynamic of the song’s evolving form.(18) The song has several loose sections that progressively swell in texture and dynamics over a continuous, looping chord progression. A gradual sense of verses, choruses and prechoruses emerges, but these distinctions aren’t clearly defined for much of the song. Of particular interest is the “you give yourself away” section, which suggests the energy build-up of a typical prechorus, but only functions as a “real” prechorus on its second appearance.(19) As shown in Example 4, a distinct pattern gradually emerges regarding repetitions of the word “you.” For the first two sections, the word occurs once in each. For the next two sections, it occurs twice in each. “You” then occurs three times in the chorus and five times in the prechorus, all of this over a gradual crescendo. But, as mentioned above, the first prechorus doesn’t lead toward a climax; rather, it withdraws into another verse with the third-person appearance of “she” and no occurrences of the word “you.” This is a critical moment: there is a sense that the song temporarily avoids the emotional climax and withdraws from direct address, but this withdrawal only serves to emphasize the subsequent insistence on “you” in the returning prechorus section (the “real,” functional prechorus) and the inevitable buildup to a climax. The third-person moments, then, are temporary retractions from the emphasis on “you,” which help articulate the overall wave-like trajectory.(20) The more the song turns toward direct address, the more emotional and pained the expression becomes.(21)

[28] Finally, as many people have pointed out, the very act of singing puts the performer in a deeply vulnerable position.(22) The climax of “With or Without You” is a perfect example. Listeners no doubt often experience this music by identifying strongly with the song persona in an empathic way. This is relevant to the pronoun substitutions because they allow for a double expression: a confession of pain and suffering both to the lover herself and to a general audience. In the crudest sense, the persona is saying, “you hurt me,” but also exposing himself to a much larger group and saying, “see how much she hurts me.” The expressiveness and emotional vulnerability, in other words, are amplified by the sense of a double address.(23)

The “Distant → Intimate” Template

[29] Lyrics can turn toward more intimate discourse at any point in a song. It sometimes happens very early on, as in Bruce Springsteen’s “Thunder Road”:

The screen door slams, Mary’s dress waves

Like a vision she dances across the porch as the radio plays

Roy Orbison singing for the lonely

Hey that’s me and I want you only. . .

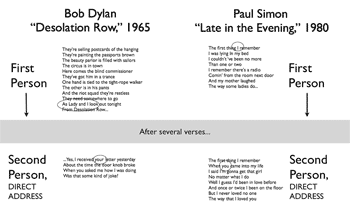

Example 5. a) Bob Dylan, “Desolation Row,” 1965. b) Paul Simon, “Late in the Evening,” 1980

(click to enlarge)

It is also quite common for songs to shift perspective closer to the end. Examples 5a–b present excerpts from lyrics by Bob Dylan and Paul Simon. In very different ways, the songs become considerably more intimate in the final verses. Such “end-oriented” moves are very common. They allow for an expressive twist that can change the entire dynamic of the song. Neil Young’s “Cortez the Killer” is a particularly interesting case. It begins with six verses of third-person, historical narrative, somewhat in the form of a traditional ballad. The first two verses set the scene:

He came dancing across the water

With his galleons and guns

Looking for the new world

and the palace in the sun.

On the shore lay Montezuma

With his coca leaves and pearls

In his halls he often wandered

With the secrets of the worlds.

But the final verse makes a startling shift into reflective, first-person reminiscence:

And I know she’s living there

And she loves me to this day

I still can’t remember when

Or how I lost my way.

[30] This last verse is striking not just because it introduces a personal love story into the wider historical narrative, but also because the singer suddenly takes on the role of a diegetic character.(24) The song is no longer sung by Neil Young as a contemporary narrator, but by a survivor of the Spanish conquest. The song hinges on the contrast between human suffering on a massive scale versus the individual pain of lost love.

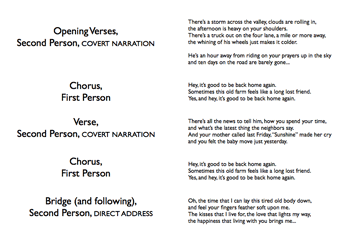

Example 6. John Denver, “Back Home Again,” 1974

(click to enlarge)

[31] Especially interesting are songs that seem to be entirely structured by carefully controlled changes in the singer’s subject position. This can happen even in otherwise “simple” songs. Consider John Denver’s “Back Home Again” (Example 6). The first two verses feature covert, second-person narration. This creates a more intimate atmosphere than third person, but it ultimately has a similar effect. The song introduces a particular character from the standpoint of a hidden narrator: the narrator speaks of a woman who waits for her loved one, presumably her husband, to return from the road, but instead of referring to “her,” the narrator uses the more intimate pronoun “you.”

[32] The subsequent chorus involves a substitution of the song’s persona. In place of covert narration, the diegetic song now comes from the perspective of the homecoming protagonist. Although it isn’t made clear yet, it is possible that the narrator has now taken on the role of the trucker—the man referred to as “him” in the prior verse. Yet if that is the case, the song does not proceed in chronological order (which is not uncommon in verse-chorus forms). The subsequent verse returns to the covert narration, and the song’s “camera” re-focuses on the woman waiting for her husband to reveal a fuller picture—learning about her neighbors, her mother, and the baby in her belly. The first chorus, then, is a jump-cut to the future, or perhaps even a fantasy in the mind of the waiting woman.

[33] The second chorus returns to the trucker’s perspective (“Hey, it’s good to be back home again”). This time, however, the substitution sticks. The bridge section that follows confirms this with the first appearance of both “I” and “you.” The song’s central idea (homecoming) is thus reinforced dynamically with the narrative switch from a “distant” narrator to a fully present, diegetic character. Throughout the song, John Denver adopts a persona that consistently refers to the woman with an affectionate “you,” first as a narrator, then as a partner. But the progression towards greater intimacy is unmistakable.

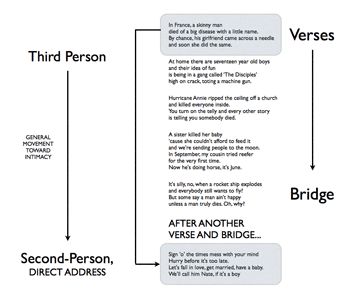

Example 7. Prince, “Sign O’ the Times,” 1987

(click to enlarge)

[34] Another example of a gradual progression occurs in Prince’s “Sign o’ the Times” (Example 7). The initial verses dispassionately catalogue various global and domestic tragedies. The narrator first sings about a couple that dies of AIDS in France and then begins a move toward greater intimacy by turning attention toward “home,” where we learn about gang violence, a deadly hurricane, poverty, matricide, and drug addiction. The last of these—addiction to heroin—is something that happens to the narrator’s cousin. This reference to a family member is significant, because it begins to draw all of these large-scale calamities into the orbit of the narrator himself. It is a subtle turn toward intimacy that ultimately prepares for the bridge, a clear shift in expressive register, where the singer breaks out of the limited melodic range of the verses and begins to adopt a more reflective, philosophical first-person stance, despite avoiding the pronouns “I” or “me.” Instead of a simple list of terrible facts, he begins to use the interrogative voice: “It’s silly, no?” And all of this leads to the direct address at the end: “let’s fall in love, get married, have a baby.”

[35] The ending offers a clear contrast with the opening story about the French couple that dies of AIDS. Whereas they were introduced from a distant, third-person perspective, the couple at the end is fully present with second-person, direct address. In fact, the ending presumably offers a “clarification” in that all of the lyrics might be interpreted as an address to the song persona’s lover—a setup for the eventual proposal at the end. But notice that this proposal is sung with the same dispassionate voice heard from the beginning. And the silliness of the final rhyme—“if it’s not too late

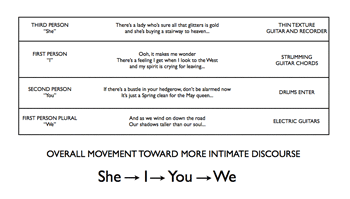

Example 8. Led Zeppelin, “Stairway to Heaven,” 1971

(click to enlarge)

[36] A more complex example is Led Zeppelin’s “Stairway to Heaven.” As shown in Example 8, the song generally conforms to the “distant → intimate” template, but it also resists the pattern in some significant ways. Up until the famous entrance of John Bonham’s drums, the progression toward intimacy is fairly obvious, with each shift accompanied by a specific change in the music. It begins with a thin, “early music” sound, complete with a lament bass and a mournful recorder, all of which reinforce the third-person, “once-upon-a-time” aspect of the lyrics. The song’s persona then adopts a more reflective, first-person perspective when the song shifts into strumming guitar chords and brief suggestions of a major key. Roughly two minutes after that, Bonham’s drums initiate the move toward direct address, completing the progression from “she” to “I” to “you.”

[37] But the song soon shifts toward the first-person plural (e.g., “as we wind on down the road”) and the overall crescendo in texture and dynamics suggests a gathering of forces. There is, perhaps, something “intimate” about this turn toward “we”—it invites the listener into the song’s Tolkienesque world—but the overall shift toward the explosive electric guitars seems strikingly less intimate than the thin, quiet texture of the opening. Moreover, the song ends with a return to the third-person narration from the beginning, except now with a lonely, unaccompanied solo voice (a reminder of how far we have come). The entire song, then, involves formal divisions that are closely linked with important shifts in narrative perspective: although the “distant → intimate” template is a salient part of the process, it involves complexities that resist any easy classification.(25)

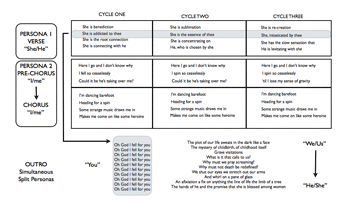

Example 9. The Patti Smith Group, “Dancing Barefoot,” 1979

(click to enlarge)

[38] A final example of address that moves toward intimacy, also quite complex, is “Dancing Barefoot,” from the Patti Smith Group’s 1979 album Wave. This is a song about hypnotic obsession, drawing together themes of sex, drugs, and religion. As shown in Example 9, the main body of the song features three cycles through a familiar verse→ prechorus→ chorus pattern. The verses are sung by a darkly seductive persona who tells of the narcotic obsession between two lovers. Especially noticeable is the repetitive and ungrammatical use of the pronouns “she” and “he,” which help reinforce the strange, incantatory feel of the music. The characters have essentially been reduced to one-syllable names—“she” and “he”—possibly suggesting the universality and consistent historical recurrence of this situation. Smith primarily adopts the position of a third-person narrator, telling what happens to “she” and “he,” but she also uses the word “thee,” which suggests an initial direct address to the male lover: “she is addicted to thee.” It is an archaic term, resonating with some of the other religious words and phrases that appear elsewhere in the lyrics. Its appearance here is surely motivated, at least in part, by the obsessive rhyming with long-e sounds: “she,” “he,” and “thee.” (In practical terms, it would sound clumsy to repeat “he” at the end of both the second and fourth lines.) But it also suggests that the narrator isn’t entirely removed from the story. Though she narrates as if from a distance, she is also capable of addressing the lovers directly.

[39] This initial direct address to the male lover eventually resonates with the climactic direct address at the song’s end: “Oh God I fell for you.” At that point in the song, there has been a clear substitution of the singing persona: “she” has been replaced with “I,” and “thee” has been replaced by “you.” But this crucial movement—from an external narrator to the addicted woman herself—first happens with the move from the verse into the prechorus. The contrast is unmistakable. Whereas the persona in the verses articulates confident declarative sentences, the persona of the prechorus and chorus is full of doubt, confusion, and powerlessness. She isn’t in control of her own body.

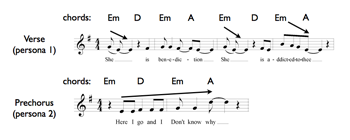

Example 10. Verse and Prechorus melodies in “Dancing Barefoot”

(click to enlarge)

[40] This substitution from “persona 1” to “persona 2” is reflected in the music. The chords in the prechorus are the same as the verse, but the melody is considerably different. In the verses, the narrator is melodically grounded in the tonic of E minor (See Example 10). Each line of text features descending gestures from G to E and B to E. The tonic note is articulated with each utterance of “she,” “thee” and “he.” But when the prechorus begins—when the singer adopts the position of the entranced woman—the music makes a dramatic shift. The melody breaks the prior pattern with a vigorous ascent, capped by an energetic leap up to D, the highest note of the vocal line (and a dissonant, non-chord tone). This is especially expressive in contrast with the prior descending gestures that were so strongly anchored to the E-minor tonic. Eventually, this prechorus will be associated with a loss of gravity, an idea that is already foreshadowed here (although, ironically, it is also the melody that sets “Oh God I fell for you.”).

[41] The energy of the ascending pre-chorus melody surges into the chorus, which now features both a new melody and a new chord progression. But the only remaining shift in perspective occurs in the outro when Smith’s voice splits in two. On the one hand is the repetitive direct address: “Oh God I fell for you.” This is an extension of the persona from the prechorus and chorus (those sections describe a present-tense process, but here the past tense suggests that the hypnosis is complete). On the other hand, a second persona simultaneously speaks abstract poetry with a heavy emphasis on the first-person plural pronouns “we” and “us.” This could be interpreted in several ways: it could be heard as an epilogue of sorts, with Smith-as-narrator now addressing the audience directly (“we” referring to everyone). It could be interpreted as the continued voice of the obsessed woman—perhaps a future version of herself—speaking to her lover directly (“we” referring to the couple). It could also be a return to the first persona, the narrator of the verses. This latter possibility seems to be confirmed at the very end of the song with the reappearance of “she” and “he”: “the hands of he and the promise that she is blessed among women.” At the very least, the emphasis on “we” and “us” suggests a circular return of sorts, perhaps even a resolution of the song’s many shifting perspectives.

[42] Rather than explore any of these particular interpretations in depth, I simply want to emphasize here the importance of the “distant → intimate” template for this song. Like many others, it is structured by crucial shifts in lyrical perspective that ultimately move in the direction of a climactic direct address. The song has much more to it than that singular trajectory, but its unique realization of the pattern is especially expressive.

[43] The following section discusses songs that move in the opposite direction (away from intimacy), but this must be prefaced with a necessary caveat: “distance” and “intimacy” are highly subjective terms; they suggest an emotional relationship that can be conveyed in ways that have nothing to do with the rhetorical complexities of shifting pronouns. Moore, for instance, draws on the psychology of “interpersonal distance” to formulate a variety of ways that songs project different degrees of intimacy and distance. This includes different “zones” that range from “intimate” to “public,” each determined by detailed features such as dynamics, vocal articulation (whispers vs. shouts), and the balance between voice and accompaniment (2012, 186-87). My overall argument—that songs frequently move toward more intimate discourse—is based on a narrow, but significant, part of this broader picture. Songs such as “Stairway to Heaven” show how movement toward intimacy in one domain—a switch from third-person to direct address—can be challenged by a move away from intimacy in other domains (following Moore, we might identify a shift into a more “public” zone based on the gradual increase in texture and dynamics along with the emphasized first-person plural).(26) Thus, although many of the songs that conform to the “distant → intimate” template will do so in obvious and unequivocal ways, we should never close ourselves off to more subtle and ambiguous interpretations. My argument here is based on general features that appear across a great many songs, but any individual close readings would require attentiveness to much more than the deployment of pronouns.(27)

Alternatives

[44] The pervasiveness of the “distant → intimate” template sets in relief a variety of songs that markedly reverse the pattern by moving away from intimate discourse. Such songs are rare, but not to the point of insignificance. “The Boxer,” by Simon and Garfunkel, is a fairly clear representative. The majority of the lyrics involve first-person narration—“I am just a poor boy though my story’s seldom told”—but the final verse switches to a more distant third-person narrator: “In the clearing stands a boxer and a fighter by his trade.” We don’t know who sings this last verse (it could be the same narrator from before, only now telling a story within a story), but the switch to a more distant perspective reinforces the loneliness and despair that can be heard throughout the rest of the song. A similar effect happens in “(Don’t Fear) The Reaper” by Blue Öyster Cult. The first two verses are a direct address: “we can become like they are

[45] Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” is famous for its many alternative sets of lyrics. Though the studio version from the 1984 album Various Positions contains only four verses, Cohen often sings additional verses in live performances and recordings. Most of these verses are addressed to various shifting individuals (e.g., “I used to live alone before I knew you.”). But Jeff Buckley’s famous cover from the 1994 album Grace ends with a verse that is somewhat of an exception: the “you” appears to be a generic, impersonal you (pronounced “ya” in the Buckley version). It isn’t addressed to anyone in particular, other than the likely possibility that he’s addressing himself (with “ya” replacing “me”):

Maybe there’s a God above

But all I’ve ever learned from love

Was how to shoot somebody who outdrew ya

It’s not a cry you hear at night

It’s not somebody who’s seen the light

It’s a cold and it’s a broken Hallelujah

Buckley’s version is far more somber than the Cohen original, and the prevailing sense of isolation is reinforced by this fifth and final verse. The effect is of an unmistakable retraction, a sense of movement away from the intimacy of direct address. Like the other songs above, the final gesture, a “stepping backward,” accentuates the overall melancholia of the entire song.

Concluding Thoughts

[46] In his monograph Performing Rites Simon Frith argues that “the use of language in pop songs has as much to do with establishing the communicative situation as with communicating” (1996, 168). This is a broad statement that covers far more than the specific shifts in perspective that I explain above. It addresses all of the complexities that inhere in pop songs in general, including the tangled relationships between autobiographical singers, their “star” personas, their fictional song personas, and the various shifts in language, vocal timbre, gesture, and theatricality that inevitably arise in almost every song. But Frith’s insistence on the importance of “the communicative situation” is instructive. As we have seen, basic questions about who is singing to whom can become a fruitful catalyst for analytical engagement. Each of the songs referenced above could be explored in far more depth—and using the “distant → intimate” template as a foundation for close readings of individual songs is an obvious possibility for future work in this area—but there are also two other critical areas to consider: one statistical, the other historical.

[47] In terms of statistics, we still know very little about how often songs engage in the kinds of dynamic discourse that I have outlined above. Unfortunately, providing such information is no easy task. The inherent ambiguities in many song lyrics make it difficult to provide any clear, objective data about how many songs engage in substitutions or clarifications with regard to the singer’s perspective or the nature of the addressee(s). Nevertheless, even a loose, tentative accounting would be a step forward. Corpus studies on this topic would help form a necessary backdrop against which we could understand the particulars of any given song. Are certain patterns characteristic of particular singer-songwriters? Are there discernible trends across genres? And do these patterns change over time?

[48] This last question relates to broader historical issues. My focus thus far has been primarily with classic rock songs from the 1960s, 1970s, and 1980s. But when did it become common for songs to feature distinct shifts in lyrical discourse? We know that such shifts have been a part of lyric poetry for centuries, but when did they become a common aspect of contemporary song lyrics? Do these shifts relate to prior traditions in folk music or the blues? Are they a common feature in the songs of Tin Pan Alley? Were they related to the late ‘60s interest in beat poetry? An in-depth study of these historical trends would help provide context for the analysis of music-lyric interaction in more recent repertoire,(28) and would also help provide a foundation for similar research on other genres, including country, heavy metal, and hip hop.

[49] Most importantly, though, a focus on the various changes in the “addresser/addressee” relationship simply offers new ways to approach the complicated interaction between music and lyrics in general. Analysis of lyrics inevitably generates questions of meaning: What is the song about? But song lyrics are more than just riddles to be solved, and the way they affect us often has less to do with any concrete meanings than it does with a general expressive stance: someone telling us a story, confessing their jealousy, or professing their love. As demonstrated above, this can involve considerable complexity. For Frith, “to sing a lyric doesn’t simplify the question of who is speaking to whom; it makes it more complicated” (1996, 184). These complications can be vexing, but they are also an invitation for deeper engagement—an invitation to track the various paths from “me” to “you.”

Matthew L. BaileyShea

University of Rochester and the Eastman School of Music

Rochester, NY 14534

matt.baileyshea@rochester.edu

Works Cited

Abbott, H. Porter. 2008. The Cambridge Introduction to Narrative. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Assayas, Michka. 2005. Bono: In Conversation. New York: Riverhead Books.

Brackett, David. 2000. Interpreting Popular Music. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

Bradby, Barbara. [1988] 1990. “Do-Talk and Don’t-Talk: The Division of the Subject in Girl-Group Music.” In On Record: Rock, Pop, and the Written Word, ed. Simon Frith and Andrew Goodwin, 341–68. New York: Pantheon Books.

—————. 2005. “She Told Me What to Say: The Beatles and Girl-Group Discourse.” Popular Music and Society 28, no. 3: 359–90.

Caws, Mary Ann. 1988. “Strong-Line Poetry: Ashbery’s Dark Edging and the Lines of Self.” In The Line in Postmodern Poetry, ed. Robert Frank and Henry Sayre, 51–59. Urbana and Chicago: University of Illinois Press.

Clercq, Trevor de. 2012. “Sections and Successions in Successful Songs.” PhD diss., Eastman School of Music.

Covach, John. 2005. “Form in Rock Music: A Primer.” In Engaging Music: Essays in Music Analysis, ed. Deborah Stein, 65–76. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Culler, Jonathan. 1975. Structuralist Poetics: Structuralism, Linguistics, and the Study of Literature. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Day, Aidan. 1988. Jokerman: Reading the Lyrics of Bob Dylan. Oxford and New York: Basil Blackwell.

Durant, Alan. 1984. Conditions of Music. London: MacMillan.

Elicker, Martina. 1997. Semiotics of Popular Music: The Theme of Loneliness in Mainstream Pop and Rock Songs. Tübingen: Gunter Narr Verlag.

Everett, Walter. 1999. The Beatles as Musicians: Revolver Through the Anthology. New York and Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fludernik, Monika. 2001. “New Wine in Old Bottles? Voice, Focalization, and New Writing.” New Literary History 32, no. 3: 619–38.

Frith, Simon. 1996. Performing Rites: On the Value of Popular Music. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Genette, Gérard. 1980. Narrative Discourse. Trans. Jane E. Lewin. Ithaca: Cornell University Press.

Griffiths, Dai. 2003. “From Lyrics to Anti-Lyric: Analyzing the Words in Pop Song.” In Analyzing Popular Music, ed. Allan F. Moore, 39–59. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hennion, Antoine. 1983. “The Production of Success: An Anti-Musicology of the Pop Song.” Popular Music 3: 159–93.

Jakobson, Roman. 1971. “Shifters, Verbal Categories, and the Russian Verb.” In Selected Writings II. The Hague: Mouton.

Jespersen, Otto. 1924. The Philosophy of Grammar. London: Allen and Unwin.

Lacasse, Serge. 2006. “Stratégies narratives dans ‘Stan’ d’Eminem: le rôle de la voix et de la technologie dans l’articulation du récit phonographique.” Protée 34, nos. 2–3: 11–26.

Letts, Marianne Tatom. 2010. “‘I’m Not Here, This Isn’t Happening’: The Vanishing Subject in Radiohead’s Kid A.” In Sounding Out Pop: Analytical Essays in Popular Music, eds. Mark Spicer and John Covach, 214–43. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

McHale, Brian. 2009. “Beginning to Think About Narrative in Poetry.” Narrative 17, no. 1: 11–30.

Moore, Allan F. 2012. Song Means: Analysing and Interpreting Recorded Popular Song. Burlington and Surrey: Ashgate.

Murphey, Tim. 1992. “The Discourse of Pop Song.“ TESOL Quarterly 26, no. 4: 770–74.

Neal, Jocelyn. 2007. “Narrative Paradigms, Musical Signifiers, and Form as Function in Country Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 29, no. 1: 41–72.

Negus, Keith. 2012. “Narrative, Interpretation, and the Popular Song.” The Musical Quarterly 95: 368–95.

Nelles, William. 1990. “Getting Focalization into Focus.” Poetics Today 11, no. 2: 365–82.

Nicholls, David. 2007. “Narrative Theory as an Analytical Tool in the Study of Popular Music Texts.” Music & Letters 88, no. 2: 297–315.

Petrie, Keith J., James W. Pennebaker, and Borge Sivertsen. 2008. “Things We Said Today: A Linguistic Analysis of the Beatles.” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 2, no. 4: 197–202.

Rolling Stone. 2011. http://www.rollingstone.com/music/lists/the-500-greatest-songs-of-all-time-20110407.

Simon, Julia. 2013. “Narrative Time in the Blues: Son House’s ‘Death Letter’ (1965).” American Music 31, no. 1: 50–72.

Stephan-Robinson, Anna. 2009. “Form in Paul Simon’s Music.” PhD diss., Eastman School of Music.

Summach, Jay. 2011. “The Structure, Function, and Genesis of the Prechorus.” Music Theory Online 17, no. 3.

Tagg, Philip. 2012. Music’s Meanings: A Modern Musicology for Non-Musos. New York and Huddersfield: The Mass Media Music Scholar’s Press.

Temperley, David. 2007. “The Melodic-Harmonic ‘Divorce’ in Rock.” Popular Music 26, no. 2: 323–42.

Vendler, Helen. 2002. Poems, Poets, Poetry: An Introduction and Anthology. Boston: Bedford and St. Martin’s.

Vickers, Nancy J. 1988. “Vital Signs: Petrarch and Popular Culture.” Romantic Review 79, no. 1: 184–94.

Warren, Rosanna. 2008. Fables of the Self: Studies in Lyric Poetry. New York and London: W.W. Norton & Company.

Footnotes

* I’d like to thank a number of friends and colleagues for providing helpful feedback, including Seth Monahan, Robert Lagueux, Jay Summach, Sumanth Gopinath, Benjamin Givan, and John Covach. I’m also deeply grateful to Nicole Biamonte and Karen Bottge for their many helpful suggestions throughout the editorial process.

Return to text

1. The literature on this topic is too vast to offer a comprehensive survey. Some recent work that has been especially influential includes Frith 1996, Brackett 2000, Moore 2012, and Tagg 2012, which offer excellent introductions. Griffiths 2003 surveys general issues with the analysis of song lyrics. Nicholls 2007, Negus 2012, Simon 2013, and Neal 2007 provide important discussions of narrative in popular song.

Return to text

2. To my knowledge, there has never been an extensive scholarly treatment of this topic. There has, however, been significant research that deals with the importance of pronoun usage in popular music, sometimes touching on questions regarding “distance” and “intimacy” even if only in an ad hoc way. Antoine Hennion (1983) and Alan Durant (1984) explain how pronoun shifters, such as “I” and “you,” form a crucial component of listener identification in popular music. The topic also comes up in both Martina Elicker’s research on loneliness in popular music (1997) and Nancy J. Vickers’ work on Petrarch and popular song (1988). Barbara Bradby’s work (1990 and 2005) is essential reading on this topic, but she primarily addresses questions regarding gender and identity rather than the kinds of “dynamic discourse” that I outline in this paper. As discussed above, Nicholls 2007 and Negus 2012 both include sensitive considerations of pronouns and point of view in individual songs, but only as part of larger arguments about the role of narrative in popular music. Moore 2012 discusses the importance of distance and intimacy, but with a primary focus on how different aspects of the “sound-box” create certain effects (summarized in paragraph 43 below). More statistically oriented research on pop music pronoun usage can be found in Murphey 1992, and Petrie, Pennebaker, and Sivertsen 2008.

Return to text

3. Throughout this paper, I frequently refer to “song personas,” which typically signifies a complex merger of the real-life singer(s), their star personas, and the constructed characters that they embody in any particular song. For more on this topic, see Frith 1996, 183-85.

Return to text

4. Example 1 is based on information about whether or not singing personas and addressees are explicitly acknowledged over the course of a song. It does not, however, cover the various complex ways that listeners identify with different personas in the song (e.g., the “I” or the “you”). Although listener identification is strongly related to the various issues I address here, it is too complex a topic to cover in this paper. For some excellent observations on the issue, see Moore’s chapter on “persona” (2012, 179-214).

Return to text

5. These shifts in perspective are a significant concern in the field of linguistics. Research on pronouns and other deictics can be traced primarily to the work of Otto Jespersen (1924) and Roman Jakobson (1971).

Return to text

6. As will be discussed below, consistent third-person narratives are remarkably rare in popular music. Although many songs have third-person stories, they typically shift toward some form of address eventually (e.g., the Beatles’ “Eleanor Rigby” is primarily a third-person song, but there is a notable shift toward general address with the line “Ah, look at all the lonely people”).

Return to text

7. It isn’t always clear in such cases whether or not the subject of the address can actually hear the narrator. In the first verse of “Do It Again,” we might imagine the narrator as an externalized version of the subject himself (in other words, he is speaking to himself, using the pronoun “you”). In that situation, he would, of course, be able to “hear” himself. But we might also imagine the narrator simply floating above the character, using “you” instead of “he” but not actually addressing this character in an audible way. Ultimately, as “Do It Again” progresses, the lyrics shift more toward direct address, especially with the introduction of the pronoun “us” in the third verse (“you swear and kick and beg us”).

Return to text

8. There are obvious limitations to using any specific list as a basis to make generalizations about rock music. Moreover, it is essentially impossible to produce decisive, objective data about narrative modes given the degree of ambiguity in many rock lyrics (hence the loose percentages given above). Nevertheless, the Rolling Stone list provides a useful starting point for an informal investigation.

Return to text

9. Perhaps the most obvious assumption is that “is” is the missing verb (“Everything is in its right place”) but one of several other verbs could also be missing (e.g., “Put everything in its right place” or “Everything belongs in its right place”).

Return to text

10. The existence of this pattern in lyric poetry should sensitize us to the many notable shifts toward intimate discourse in nineteenth- and twentieth-century art songs. Consider, for instance, the haunting shift toward direct address at the end of Schubert’s “Der Doppelgänger,” which coincides with a dramatic modulation from B minor to D-sharp minor.

Return to text

11. Anna Stephan-Robinson makes a similar point about changes in perspective at the chorus section (2009, 240). Temperley argues that many rock songs fit a “loose-verse/tight-chorus” pattern in which the verses feature a “melodic-harmonic divorce” and the choruses feature greater coordination between melody and accompaniment. He associates this with a sense of individual freedom in the verses contrasting with greater unity in the choruses (2007, 337). Although this doesn’t necessarily have anything to do with pronoun shifts, it certainly has the potential to be aligned with a move toward greater intimacy. More generally, the idea that the chorus is often the emotional center of the song is supported by these shifts toward more intimate discourse.

Return to text

12. Other famous examples of this pattern include “Don’t Stand So Close to Me” by the Police, “Shooting Star” by Bad Company, “I Want to Know What Love Is” by Foreigner, and “You Can Call Me Al” by Paul Simon. For overviews of common formal sections and their functions in rock, see Covach 2005 and de Clercq 2012.

Return to text

13. Everett discusses how Lennon intentionally wrote the lyrics for “I Am the Walrus” to be as puzzling as possible (1999, 133).

Return to text

14. Note that complexity with regard to shifts in discourse is not necessarily related to complexity in other domains. Simple tunes can shift lyrical points of view quite often and songs with staggeringly complex music and lyrics can maintain a consistent mode of discourse throughout.

Return to text

15. Nicholls (2007) is right to complain that popular music has been underrepresented in narrative theory, but—probably non-coincidentally—literary scholars seem to feel the same way about a perceived lack of research on narrative in poetry (see McHale 2009). Also, though there has been scant research on narrative theory and popular music in Anglophone publications, there have been a number of important studies in other languages. See Lacasse 2006 for a representative example.

Return to text

16. Bono recalled this event in a conversation with Michka Assayas saying, “I’m not content with the distance between the crowd and the performer. I’m always trying to cross that distance. I’m trying to do it emotionally, mentally, and, where I can, physically” (2005, 210).

Return to text

17. In a survey of seventy-seven U2 songs, I found that roughly forty-four percent involved at least one clear shift in the relation between song persona(s) and addressee(s).

Return to text

18. I’m indebted to Jay Summach for his thoughts on the song’s form, many of which I’ve adopted here.

Return to text

19. See Summach 2011 for an excellent introduction to the role of the prechorus in popular music. Also, though I interpret the “you” in this section as a reference to the persona’s lover, it is also entirely plausible for the “you” to represent the persona himself (a form of internal address).

Return to text

20. The sense of retraction is underscored by Bono audibly inhaling at the start of the second third-person verse on the studio version of the song.

Return to text

21. Although this song twice shifts into third-person narration, I don’t see it as a reversal of the normative pattern (i.e., movement away from, rather than toward, intimacy). There are some songs, discussed below, which convincingly move toward a more distant perspective, but here the movement is only temporary and only serves to accentuate the ultimate return to more intimate discourse.

Return to text

22. Frith’s discussion of this aspect is especially illuminating (see 1996, 172-73).

Return to text

23. We might also consider that the shifting pronouns simply offer more ways for listeners to identify with the song in general. Mary Ann Caws discusses pronoun shifts in a poem by John Ashbery by saying, “The switching back and forth between pronouns

Return to text

24. “Diegetic” refers to situations where the song’s persona is a character in the story world of the song (as opposed to “extra-diegetic” or “non-diegetic,” where the persona takes on the role of an external narrator).

Return to text

25. As Seth Monahan pointed out in private correspondence, we might also conceive of this song as a temporal switch from distance to proximity, a movement from a mythic past (represented by the “early music” sounds of the opening and the third-person narration) to a modern present (with the heavy, electric-guitar vamp at the end). The persona begins with a story from the past, but ends by emphasizing its meaning in the present.

Return to text

26. Durant (1984, 205-6) discusses the move toward plural direct address in the choruses of “We Are Family” by Sister Sledge (“get up everybody and sing”), arguing that it provides a way of establishing group identity.

Return to text

27. Moore offers several nuanced discussions of movement between distance and intimacy, often focusing on timbre, vocal delivery, and spacing with regard to the overall sound-box. A good example is his discussion of Hendrix’s “If Six Was Nine” (2012, 290).

Return to text

28. In private correspondence, Benjamin Givan pointed out the presence of the “distant → intimate” template in Bing Crosby’s “White Christmas” and George and Ira Gershwin’s “A Foggy Day.” My sense is that such shifts are indeed quite common in the Tin Pan Alley repertoire, but I have not yet done an extensive corpus study.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2014 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Rebecca Flore, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

17826