Review of Joe Mulholland and Tom Hojnacki, The Berklee Book of Jazz Harmony (Berklee Press, 2013) and Dariusz Terefenko, Jazz Theory: From Basic to Advanced Study (Routledge, 2014)

Keith Salley

KEYWORDS: jazz theory, jazz pedagogy, chord-scale theory, harmonic function, hypermeter, form

Copyright © 2015 Society for Music Theory

[1] Jazz theory texts have certainly come a long way since the 1970s and 1980s, when generalities and street talk often took precedence over serious academic rigor. The textbooks under review here are both robust volumes with much to offer the educated musician. Joe Mulholland and Tom Hojnacki primarily address jazz harmony—though they cannot avoid touching upon other fronts—in a way that is at once both conservative and forward-looking. They are the chairs of the Harmony Department at the Berklee College of Music, and their textbook, The Berklee Book of Jazz Harmony, presents a system that has been taught there since the 1960s.(1) The scope of Dariusz Terefenko’s Jazz Theory: From Basic to Advanced Study is considerably broader. It addresses topics that do not always appear in jazz theory texts, such as jazz rhythm, music fundamentals (a very thorough treatment), and even post-tonal jazz with a primer on pc-set theory.

[2] Both books include digital audio resources. Terefenko provides a play-along DVD and a companion website.(2) The website is open to everyone, requiring no password and stipulating no window of time for user access. It features ear-training exercises, recordings of examples, appendices, and an extensive workbook of written exercises. Mulholland and Hojnacki provide a CD with recordings of original compositions that serve as examples in the text. The Berklee Book would benefit from including some opportunities for readers’ self-assessment. However, for the present edition such objectives are somewhat beyond (or peripheral to) the intent of the book, which is simply to introduce Berklee’s harmonic system to new readers.

[3] Despite their differences, these books do have enough in common to invite comparison. Consider the following passages, excerpted from relatively early chapters in each, where the authors differentiate jazz from other tonal musics. Mulholland and Hojnacki do this at the very outset:

One thing that distinguishes mainstream jazz harmony from other tonal styles is the tremendous amount of harmonic color that arises due to the pervasive use of tertian extensions of the basic chord types. Jazz musicians refer to these notes as tensions. Jazz harmony is also characterized by a strong progressive drive or forward propulsion analogous to the rhythmic character of the music. (1)

While the authors dedicate most of their energy to explaining jazz’s “tremendous amount of harmonic color,” they pay more than lip service to the “forward propulsion analogous to the rhythmic character of the music.” In several cases, they even go so far as to consider how that propulsion works within jazz’s rhythmic framework (a topic addressed in more detail below).

[4] Terefenko makes a comparable statement that summarizes an introduction to tonic, pre-dominant, and dominant functions:

As will be demonstrated time and time again, functional tonality in jazz has different properties than that of common-practice classical music. These properties are represented by a unique set of rules dictating the unfolding of harmonic function, voice-leading conventions, and the overall behavior of chord tones and chordal extensions. (26)

Shortly thereafter, he makes the following observation about the relationship between harmony and rhythm, which further aligns his theory of jazz with that of Berklee’s method:

In this early exposition of harmonic progressions, we cannot ignore other important factors that contribute to the concept of tonality, such as metric placements and duration of chords. (31–32)

[5] Claims that jazz is a different kind of tonal music are hardly profound. However, they are significant simply because jazz theory texts do not normally make such observations. These authors use similar differentiations to situate their discourses within spaces that allow critical inquiry from academically informed readers. In doing so, they establish points of departure for presenting innovative ideas on such topics as harmony and form. This review compares these two texts by addressing their ideas on these topics. In the harmonic domain, I consider the authors’ views on tonal function and chord-scale theory. In the domain of form, I explore their comments on both phrase models (and their combinations) and the relationships between harmony and meter that influence our perception of larger-scale rhythm.

[6] A positive attribute of both texts is that they dedicate a significant amount of space to tonal function.(3) This subject is particularly relevant to jazz, where function and chord type can have very close yet quirky relationships. And though the concept of tonal function is not elusive in itself, it is broad enough for different musicians to interpret and explain it differently. The texts under consideration offer quite dissimilar explanations. To Mulholland and Hojnacki, harmonic function accounts for “the relationship of a chord to its tonal center” (3). The authors introduce tonic, subdominant, and dominant functions, noting the primary representatives (Imaj7, IVmaj7, and V7) for each. At first, this seems innocuous enough. However, their explanation of the subdominant function cites the voice-leading tensions that arise when IVmaj7 resolves to Imaj7 (even contrasting it to a resolution from V7 to Imaj7), rather than addressing the inclination of subdominant chords to lead to dominant chords. Of course the authors are aware of this tendency, but to them, chordal behavior does not define harmonic function.

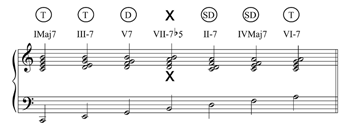

Example 1. Mulholland and Hojnacki, The Berklee Book of Jazz Harmony, Ascending Cycle 3 Pairs, page 11

(click to enlarge)

[7] “Functional groups” account for functional roles of other diatonic chords, with iii7 and vi7 substituting for tonic, and ii7 for subdominant. What follows is a discussion of six patterns or “cycles” of root motion (ascending and descending 2nds, 3rds, and 5ths) in which diatonic harmonies pass through the key of C, exhausting all possibilities for diatonic chord succession. Example 1 shows an ascending “cycle 3,” with harmonic functions shown above the chords.(4) Within each cycle, the authors discuss functional relationships between pairs of adjacent chords, noting whether progression, retrogression, prolongation, or resolution occurs, as well as commenting on the musical effects of those connections.

[8] While Mulholland and Hojnacki do not conceptualize function in terms of the common-practice T–(P)–D–T phrase model, Terefenko does. His hierarchy has more levels as well, with dominant defined in terms of its tendency to resolve to tonic, and pre-dominant in terms of its tendency to progress from tonic to dominant. Thus, functions are presented in terms of harmonic behavior, and against a background that acknowledges the tonic’s overall influence. Membership in “functional families” (roughly analogous to the Berklee method’s “functional groups”) is also based on common tones, but here Terefenko allows chords whose roots lie a diatonic third above or below a function’s primary representative (I, IV, and V).(5) As a result, the families overlap so that vi belongs to tonic and predominant families, and—to be consistent, if not particularly reflective of practice—iii belongs to tonic and dominant families.

[9] Terefenko’s discussion of function probably agrees more with the ways most readers understand its application to tonal music in general, but rhetorically, his argument is not as easy to defend as the one in The Berklee Book. Mulholland and Hojnacki introduce each function’s representative chord and describe how active scale degrees within subdominant- and dominant-functioning chords relate to the tonic. On the other hand, Terefenko’s discussions of function (chapters 3 and 4) do not address active scale degrees and their voice-leading tendencies. In this way, he provides definitions in the manner of descriptions of chordal behavior, but offers no explanations of the factors that give rise to harmonic function.

[10] Mulholland and Hojnacki’s chord-scale theory is different from Terefenko’s in that it is initially monotonal, allowing only diatonic “tensions” (extensions beyond sevenths) on chords. In practice, this results in a more varied range of chord types in comparison to what one usually encounters in jazz theory texts. For example, some chord-scale theories recognize equivalence among all minor seventh chords, and introduce a standard or generally accepted array of extensions to sound over them. But according to The Berklee Book, extensions over iii should differ from those that sound over ii or vi. Moreover, extensions on secondary dominants should also follow this rule, so that while V/iii and V/ii both have minor seventh target chords, the former would have altered ninths (

[11] While The Berklee Book’s diatonic basis is simple in principle, complexities arise from such an enlarged harmonic palette. Mulholland and Hojnacki consider tensions that appear a half step above a chord’s root, third, fifth, or seventh in a chord scale as “harmonic avoid tones” that readers should not incorporate into voicings (21). “Avoid tones” are certainly not new to jazz theory, but here they are defined broadly enough to conflict with any of these four fundamental tones of any chord type.(6) Almost as soon as the authors introduce the idea, they allow for exceptions such as extended dominants with lowered ninths or thirteenths, as these extensions would conflict with chord roots and fifths, respectively. However, such “conflicts” are very common in practice. As a result, the authors abandon their diatonic basis for extensions on dominant chords within the first chapter and introduce five different optional dominant chord scales—possibly the earliest entrance of altered dominants in any jazz theory text (33–36). Such an early divergence from the diatonic basis is bewildering, and it is no more reassuring when the authors return to it in the following chapter to discuss extensions on secondary dominants.

[12] In generating such complexity at such an early stage, The Berklee Book raises the question of whether a simpler system of selecting harmonic extensions could exist—one, perhaps, that is not based on chord scales. After all, chord-scale theories typically recognize chords and scales as different manifestations of the same thing, reflecting in some ways the interrelated properties of dual states in quantum mechanics.(7) But Mulholland and Hojnacki do not need to have it both ways. They do not use chord scales to recommend appropriate collections in melodic improvisation, but only as a convenient way to present harmonic extensions.(8) Therefore it would seem easier to cast chord scales aside and set general preference rules, such as one that recommends raising elevenths on any major chord type unless the third is omitted. This would be simpler than assigning a scalar array of chord tones that contains a perfect eleventh while proscribing the use of that tone—or, in a more problematic case, assigning the Phrygian mode to iii7 while proscribing its characteristic tones,

[13] Terefenko’s stance on chord-scale theory differs considerably from that taught at Berklee. He acknowledges jazz’s diversity of chord types from the start, and makes no attempt to explain harmonic derivation in terms of scales. He groups four-part chords (consisting of a chord’s root, third, fifth, and either sixth or seventh) according to quality (major, minor, dominant 7th, and intermediary), and discusses the functions those qualities can fulfill. Only after imparting this information does Terefenko situate these chords within scales to illustrate relationships between function and scale degree—but he still does not use scales to illustrate or generate extensions. Even the following chapter on extended chords discusses unaltered and altered extensions without recourse to scales. Terefenko’s approach manages to avoid the issue of directly mapping chords and scales onto each other while still providing a preliminary explanation of jazz harmony that is clear.

[14] When Terefenko finally broaches chord-scale theory in Chapter 8, readers find that the topic occupies a special place in his pedagogy. In contrast to Berklee’s system, Terefenko does believe in the dual state, claiming that “any melodic line can be represented by a chord and/or harmonic progression and, conversely, any chord or harmonic progression can be horizontalized with a melodic line” (93). But beneath the surface, his theory is not as rigid as it might seem. He allows that a single scale may correspond to more than one chord, and that a single chord may correspond to more than one scale. In this light, Terefenko’s chord-scale theory is not simply prescriptive. It is also descriptive, providing a metric with which one can gauge the degree to which the harmony and melody of a passage interact with and complement each other to express a single and cohesive collection:

The interplay between the melodic line and the underlying harmonies unifies both musical dimensions. Not only does chord-scale theory control the relationship between lines and chords, but it also suggests a particular melodic and harmonic vocabulary derived from the structure of specific chords and scales. (94)

This information allows further prescriptive application, too. If a harmonic environment fails to completely express the character of a chord scale because certain tones of a mode are omitted, a musician who has read Terefenko will know to incorporate or even feature those tones in melodic improvisation.

[15] Terefenko does not define avoid tones as broadly as Mulholland and Hojnacki do, and he cites only natural elevenths on major chord types (and, inversely, major thirds on suspended dominants) and major thirteenths on minor seventh pre-dominant chords. This allows Terefenko to present a number of viable harmonic and melodic options at once for each chord type, thereby demonstrating the principle behind avoid tones in a way that is not overwhelming. The simplicity of his stance is perhaps most evident in a later chapter that discusses six-note collections. Here, he inverts the concept by supplying general aggregates (chromatic repositories of eight or ten usable tones) for each chord type from which readers can create their own chord scales.(9)

[16] Still, given such a profusion of viable collections, Terefenko advises, “when a chord does not clearly project the sound of a mode, the corresponding melodic line has to supply the missing notes from the correct scale” (103). This raises two questions. First, why is the complete expression of a chord scale always necessary in jazz improvisation? Experienced musicians have heard and played “incomplete” textures, and while these textures can seem sparse, they are hardly impoverished. Second, if a chord symbol elicits multiple chords and scales, what is the likelihood that a group of musicians will converge upon the same collection for each given chord symbol throughout a performance? Successful examples of non-convergence are unquestionably abundant in the recorded repertoire. Unfortunately, Terefenko does not address these questions in the “Basics” section where they arise, or in later “Intermediate” and “Advanced” sections.

[17] Although Mulholland and Hojnacki do not dedicate specific chapters to either rhythm or form, they refer frequently to effects created by the placement of harmonies within measures and larger metric groupings. This calls attention to a dynamic rarely considered in jazz theory. The authors do not use the terms “hypermeasure” or “hyperbeat,” but they touch upon higher-level accent patterns in the first chapter, asserting that “when the harmonic rhythm is regular but slower than the beat, the listener will still sense an alternation of strong and weak stresses” (15). Shortly thereafter, they encourage readers to be sensitive to this phenomenon: “Understanding the expectation of the listener (stable chords on strong stresses, unstable chords on weak stresses),” they advise, “affords us the opportunity to play with that expectation” (16). Chapter 2 urges readers to observe how occurrences of dominant-seventh chord types in weak metrical positions “create a sense of strong forward motion” (40). When the authors address this at a level beyond the measure, they argue that the same effect is achieved (47). This leads them to claim that secondary dominants are more likely to occur on weak metric and hypermetric stresses than on strong ones.

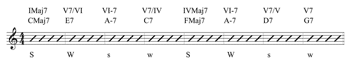

Example 2. Mulholland and Hojnacki, The Berklee Book of Jazz Harmony, Secondary Dominant on a Strong Stress, page 48

(click to enlarge)

[18] This claim is certainly a valuable contribution to jazz theory and analysis, and while there is presently no statistical evidence (i.e., no corpus analysis) to support it, such information is not necessary in a pedagogical context. To the authors’ credit, they address two notable exceptions. The first, involving V7/V in phrases that end on V, is shown in Example 2. The second exception involves tunes that begin on V7/V before progressing to V, such as Frank Loesser’s “If I Were a Bell” or George Gershwin’s “But Not for Me.” The second exception is particularly valuable, because it shows a syntactical harmonic motion that is very common in jazz but rare in other tonal musics. It hardly refutes the authors’ claims about the ways that harmony affects forward motion; rather, it bolsters the authors’ initial claim about jazz’s distinctive harmonic and rhythmic character (1). The authors return to this topic in later chapters that discuss modal interchange (124) and modal harmony (193). Such observations show how the “forward propulsion” of jazz harmony is not merely “analogous” to jazz’s rhythmic character. More accurately, that propulsion arises from it, through the interaction of harmony and form.

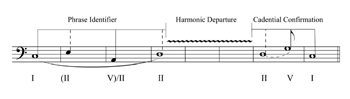

Example 3. Terefenko, Jazz Theory: From Basic to Advanced Study, Phrase Model 6, page 307

(click to enlarge)

[19] Terefenko’s chapters on form are among the book’s most valuable contributions to jazz theory. Chapter 21 takes as a point of departure eight-measure sections, which typically manifest a harmonic opening, or “phrase identifier,” a “harmonic departure” in which virtually any tonicizations or prolongations may occur, and a “cadential confirmation” (see Example 3). Terefenko parses phrases according to their identifiers. He recognizes thirteen unique phrase models and provides extensive repertoire lists for each. The purpose of these phrase models is not only to develop readers’ sensitivity to pattern recognition, thereby increasing their ability to categorize and even memorize tunes; it is also to inculcate a deeper understanding of both the variety and peculiarity of harmonic progression in standard jazz repertoire.(10) Terefenko enables readers to synthesize this understanding in three following chapters. Chapters 22 and 23 discuss AABA and ABAC song forms, qualifying those forms by key relationships among the phrase models that occupy each eight-measure section. Chapter 24 treats extended and unusual forms. Each chapter provides a detailed analysis of a standard that considers the interaction of phrase models, melody, larger-scale form, and, quite often, lyrics. This holistic approach illustrates how an integrated understanding of repertoire can inform a comprehensive performance.

[20] In addressing jazz’s ubiquitous hypermeasure, both texts draw attention to relationships between harmony and form. Because Terefenko’s phrase models are not specific with respect to harmonic rhythm, each of them is general enough to account for a variety of actual phrases. For this reason, the repertoire lists are indispensable. On the other hand, Mulholland and Hojnacki are keen to point out the specific differences that result from the harmonic placement of chords within measures and hypermeasures. They illustrate these effects in a number of original examples and compositions, but refer to standard repertoire as well. By integrating these ways of thinking about phrase structure, a dedicated student may acquire an especially sensitive understanding of form in jazz.

[21] While both texts offer much more than what I have been able to address here, this review has touched upon common topics that they treat in remarkably different ways. Those differences pertaining to chord-scale theory and form could be due to the fact that the texts address different audiences. Although improvising accompanists will find value in The Berklee Book, Mulholland and Hojnacki primarily address the developing composer/arranger who already has a strong background in traditional tonal and chord-scale theories. Terefenko addresses jazz performers in general across all levels of expertise, with much of the material in his “Advanced” section appropriate for the professional performing jazz musician with a strong theoretical bent. Bearing this difference in mind, the reader who wishes to gain a more complete understanding of jazz theory should definitely acquire both texts.

Keith Salley

Shenandoah Conservatory

Shenandoah University

1460 University Drive

Winchester, VA 22601

ksalley@su.edu

Works Cited

Coker, Jerry. 1964. Improvising Jazz. Simon & Schuster, Inc.

Jaffe, Andy. 2009. Jazz Harmony. 3rd ed. Schott Music.

Levine, Mark. 1995. The Jazz Theory Book. Sher Music Co.

Nettles, Barrie. 1987. Jazz Harmony. 3 vols. Berklee College of Music.

Nettles, Barrie and Richard Graf. 2002. The Chord Scale Theory and Jazz Harmony. 2nd ed. Advance Music.

Footnotes

1. For this reason, the book’s content and structure overlap considerably with earlier publications by Barrie Nettles (1987 and 2002), who also taught at Berklee. In general, Mulholland and Hojnacki may be credited with clarifying, extending, and making more widely available the same approach.

Return to text

2. The DVD has no video content. The companion website is available at

http://www.routledgetextbooks.com/textbooks/9780415537612/default.php.

Return to text

3. Texts such as Coker 1964 and Nettles and Graf 2002 introduce function but do not explain the forces that give rise to them. A notable exception is a brief passage in Jaffe 2009 (29–31).

Return to text

4. While VII–7

Return to text

5. Terefenko introduces tonal function in terms of triads rather than seventh chords.

Return to text

6. In contrast, Levine (1995) limits avoid tones over major harmonies to natural elevenths that sound against thirds.

Return to text

7. For example, see Levine, who claims that “the scale and the chord are two forms of the same thing” (1995, 33).

Return to text

8. The authors seem to make an exception to this in Chapter 6, “Blues in Jazz,” where the melodic and harmonic orientations of chord scales are on relatively equal footing.

Return to text

9. Given the limitations of six-note collections in terms of interval content and cardinality, the single eight-note aggregate omits

Return to text

10. An implicit insight is that the varying sizes of the lists reflect the relative distributions of different phrase models across standard jazz repertoire.

Return to text

http://www.routledgetextbooks.com/textbooks/9780415537612/default.php.

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2015 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Tahirih Motazedian, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

10679