Review of Ian Bent, David Bretherton, and William Drabkin, eds. Heinrich Schenker: Selected Correspondence (Boydell Press, 2014)

Jan Miyake

KEYWORDS: Heinrich Schenker; digital humanities

Copyright © 2015 Society for Music Theory

[1] In this age of digital humanities, how does engagement with an online clearinghouse of documents influence a beautifully curated book of primary source documents? Heinrich Schenker: Selected Correspondence, edited by Ian Bent, David Bretherton, and William Drabkin, represents one outcome made possible by digital humanities. It builds upon Schenker Documents Online to accomplish more than the website, yet only through the twelve contributors’ participation in the online project could this volume have come to fruition.(1) Additionally, the act of collecting items for Schenker Documents Online and the possibilities for labeling and linking documents on a website has enabled and possibly inspired the enterprise of choosing a subset of Schenker’s 7000+ known documents to publish.

[2] Published by The Boydell Press and meticulously edited, Heinrich Schenker: Selected Correspondence presents twenty-six narratives, or storylines, from Schenker’s writings with translations, when available, from Schenker Documents Online, and with added commentary, interpretation, and insight from the contributors.(2) For this print volume of correspondence, Bent, Bretherton, and Drabkin have chosen and organized approximately 450 documents, spanning 490 pages, into twenty-six chapters that are grouped into six broad sections: The Early Career, Schenker and his Publishers, Schenker and the Institutions, Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, Contrary Opinions, and Advancing the Cause. They provide forty-four prefatory pages that include information on editorial method, abbreviations, and biographical notes, as well as a general introduction that sets the context for the work and describes the challenges inherent in engaging with Schenker’s massive output. Thirty-three pages of bibliography, transcription and translation credits, and index conclude the volume; the entire enterprise is supplemented by forty-three plates collected into two sets of unnumbered pages.

[3] Selected Correspondence and Schenker Documents Online share editorial styles, labels for cataloging Schenker’s correspondence, and English translations (identical except for a comma or two), yet the connections between these resources include some surprises. For example, the documents presented in this volume are not completely represented on the website. Although the documents published in Selected Correspondence have been transcribed and translated, many have not yet been uploaded to Schenker Documents Online. One hopes and assumes that eventually all of the documents in Selected Correspondence will find their way onto Schenker Documents Online.(3) The website also offers no way to read the documents in the print volume as a narrative. Finally, the electronic medium of Schenker Documents Online offers the following benefits: side-by-side translation; easy navigation to encyclopedia-like entries on persons, institutions, works, and places; and the potential to add newly discovered materials to Bent, Bretherton, and Drabkin’s storylines.(4)

[4] In both the website and the book, the editors translate documents in a way that allows their English-speaking audience to develop a sense of the ideas, persons, and relationships in Schenker’s life. Three editorial decisions in support of this translation philosophy stand out. First, they prioritize idiomatic English over literal translation. To accomplish this, they occasionally allow themselves poetic license to “enlarge slightly” upon the text, though to be sure they meticulously document such liberties (xvii). Second, they provide the complete texts of letters, even when they include discourse tangential to the chapter’s main thread. The editors believe that the comprehensive text “enables the reader to get a fuller sense of the interchange between correspondents and a better feel for the psychology of the writer (and the recipient)” (xvii). Finally, they represent missing pieces of correspondence as completely as possible. When the final version of a letter is not available they present the best version of the draft, if available. Likewise, Schenker’s abundant diary entries are used to supplement information.

[5] Bent, Bretherton, and Drabkin embrace a variety of storylines throughout the volume. In wrestling with how to choose documents from the 7000+ known documents, the editors have valued depth over breadth and have “arranged the selections in such a way as to show off Schenker’s correspondence in many different lights: artistic, intellectual, business, professional, polemical, and private, and encompassing his work in composition, performance, editing, source studies, theory, pedagogy, and analysis” (xxxi). For example, within the first of the book’s six sections, “The Early Career,” the editors present 102 documents on five topics: (1) Schenker’s early identity as a composer; (2) the reception, over a three-year span, of his composition Syrian Dances; (3) the artistic impact of performing with Johannes Messchaert; (4) Schoenberg’s music and his interest in Schenker participating in The Society for Creative Musicians; and (5) Schenker’s early, and not repeated, attempt to be an agent for a publisher that resulted in his deep engagement with the work of C.P.E. Bach.

[6] One of the book’s most compelling assets is located within the front matter (xxxii–xliv), where Bent, Bretherton, and Drabkin offer “some interpretation of and broader reflection upon the material contained in each of [the] sections with the occasional speculation that goes beyond the scope of the individual chapter introductions and the footnoting of the correspondence items” (xxxii). These reflections and occasional speculations allow readers to glimpse expert thoughts on the subject. It is unfortunate that these twelve pages of material are so sequestered; placing all of these insights within the general introduction makes it somewhat impractical to take advantage of Bent, Bretherton, and Drabkin’s knowledge on Schenker’s life and correspondence while reading a chapter.

[7] Here are overviews of two powerful insights that impact how a chapter could be read. In Section 2, “Schenker and his Publishers,” each of the four chapters’ introductions (74–75, 93–94, 106, 130–31) provides background information about the publisher, an overview of Schenker’s relationship with that publisher, and a sense of how the presented correspondence fits in with the overall correspondence.(5) By contrast, in the general introduction (xxxiv–xxxvii), Bent, Bretherton, and Drabkin summarize the different types of relationships that Schenker had with his publishers as well as the overarching thread of the publishing storyline. This background knowledge can illuminate this section’s 104 documents for the reader. The second example is drawn from Chapter 5 (“Julius Röntgen: Editing and Ornamentation”), which describes Schenker’s service as an agent and how this role led him to work on C.P.E. Bach’s music. In the general introduction, the editors advance the powerful notion that the Röntgen correspondence dating from “the years 1901 to 1903, when [Schenker’s] aspirations as composer and performer still lingered, might be seen in a new light, as the period during which editing and theorizing began to converge as the parallel, inter-related activities that were to dominate his work as a mature music scholar” (xxxiv). Owing to these twelve pages of insights, one particularly fruitful—yet cumbersome—way of enjoying this book is to flip back and forth between corresponding sections of the general introduction and the threads of correspondence within each section. In this way, a reader could draw upon and engage with the considerable expertise of the editors, using their thoughts as one lens through which to view the correspondence.

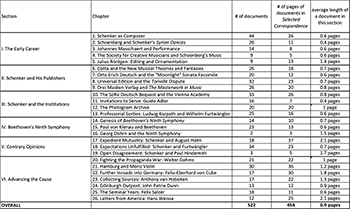

Table 1. Overview of Selected Correspondence Contents

(click to enlarge)

[8] Table 1 provides an overview of the book’s contents. Organized by section, each chapter is described in terms of number of documents, number of pages, and average length of a document.(6) This table reveals that the correspondence items with Halm, Cube and Weisse are particularly lengthy while those with Schenker’s publishers are not. It also shows that the materials considered in the chapters range from two documents (Chapter 16, “Georg Dohrn and the Ninth Symphony”) to forty-four (Chapter 1, “Schenker as Composer”). Chapters with a high volume of items certainly have the potential to tell a rich story, but what is the rationale for the chapters with only two or three documents? Chapter 16, “Georg Dohrn and the Ninth Symphony,” is remarkable for two reasons. First, translator John Rothgeb’s introduction relates a tale of discovery (251). Hellmut Federhofer, an Austrian scholar of Schenker’s life and correspondence, serendipitously found Schenker’s holograph letter to Dohrn while browsing in a bookstore. Federhofer corresponded with Rothgeb, and together they were able to identify the sender, recipient, and an inkblot-caused transcription error. Second, Dohrn and Schenker’s nuanced discussion of the famous octave motive from the second movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony results in an unusually long and comprehensive letter from Schenker that makes a strong argument for the importance of the manuscript. This two-document chapter both allows a current scholar to share a story of acquisition and provides an outstanding example of Schenker’s musicality, attention to detail, and belief in manuscript studies.

[9] The other remarkably brief chapter contains two letters and one diary entry. According to translator Arnold Whittall, Chapter 19 (“Open Disagreement: Schenker and Paul Hindemith”) is significant because “this material is the only known exchange in writing between Schenker and a leading contemporary composer to address technical and aesthetic matters” (318). Hindemith initiated the correspondence after Schenker singled him out in The Masterwork in Music I, stating “Supposing Beethoven wrote music ‘today’ like Hindemith—well then, he would be bad like him” (1994, 121). In addition to being the important contribution that Whittall describes, this brief chapter illustrates the advantages of including Schenker’s diary entries.(7) The diary entry from 30 October 1926 documents how Schenker processed what Hindemith had to say, explaining his view that Hindemith “feels hurt,

[10] One individual essential to understanding Schenker’s correspondence is underrepresented in Selected Correspondence: his wife Jeanette Schenker, also referred to as “Lie-Liechen.” Even though her presence is felt throughout this volume, outside of the approximately 100-word profile the editors provide (xxvi), they include no additional overview of the role that she played in Schenker’s life or the significance of her contributions to his correspondence.(8) The index reports sixty-four references to her, twenty-four of which are within footnotes. Most footnotes containing her name use some form of the following information: “written/draft in Jeanette’s hand with extensive/significant/many alternations by Schenker.” References to her in the body of the work occur in introductions (general and chapter) or diary entries until the late chapters on Moriz Violin and Hans Weisse. As the Schenkers were friends with the Violins, correspondence between Heinrich and Moriz typically included conventional well wishes towards each other’s spouses. The final chapter on Weisse closes solely with letters he wrote to or about Jeanette, as she was key in seeing Heinrich’s projects through at the end of his life and after his death. Throughout this volume we see many additional indications of her importance. On the topic of the Kaiser, Koslovsky writes that Dahms and Schenker’s conversation “might have become a full-blown row had it not been for the watchful eye of Jeanette” (326). In a diary entry, Heinrich relates “Lie-Liechen has a good idea to suggest a middle course between two points of view [on a publishing conundrum]!” (128). On some unusually formulated German, Bent notes “Jeanette herself seemed to doubt the latter by placing question marks over two words” (118n). And in a letter directly to Jeanette, Weisse shares “It comforts me greatly that you, having been trained in collaboration over a period of many years, and being the person most trustworthy to carry out his intentions, wish to, and will, undertake the correction of Free Composition and the music illustrations that belong to it” (480–81). It is regrettable that deeper attention was not paid to Jeanette’s significant presence and influence.

[11] In closing, Heinrich Schenker: Selected Correspondence leaves relatively little to be desired. A reader will enjoy cultivating a sense of Schenker’s presence and thoughts on topics carefully chosen by Bent, Bretherton, and Drabkin. This volume also demonstrates a benefit of Schenker Documents Online: the thousands of documents that have been collected but not yet all published in the online project have been curated into storylines and contextualized by highly regarded scholars. Heinrich Schenker: Selected Correspondence represents one possible outcome of a digital-humanities project because it interprets the data that has been amassed. It also suggests possibilities of two future initiatives for Schenker Documents Online: threads—virtual tours of a topic—that could be accessed through a tagging or filtering system, and invitations to experts to provide introductions to these threads that both set context and provide insight.

Jan Miyake

Oberlin College and Conservatory

77 W. College St.

Oberlin, OH 44071

jan.miyake@oberlin.edu

Works Cited

Schenker Documents Online, http://www.schenkerdocumentsonline.org/index.html

Schenker, Heinrich. [1925] 1994. The Masterwork in Music, Vol. 1 (Das Meisterwerke in der Music), ed. William Drabkin, trans. Ian Bent et al. Cambridge University Press.

Footnotes

1. Schenker Documents Online currently lists twenty-two contributing scholars under the leadership of Bent and Drabkin. It aims to offer “a scholarly edition

Return to text

2. There is one particularly significant difference between the two resources: Schenker Documents Online provides side-by-side translations; Selected Correspondence provides only the English texts.

Return to text

3. To locate a document from Selected Correspondence on Schenker Documents Online, search for a notable phrase or the date of the correspondence, placing the entire search string within quotation marks (e.g., “The moment I started writing, your second letter arrived”).

Return to text

4. The front matter on pages xxi–xxviii, “Biographical Notes on Correspondents and Others,” presents abbreviated versions of fifty-three of the profiles included on Schenker Documents Online.

Return to text

5. For example, the correspondence between Schenker and Cotta, the topic of Chapter 6, “Cotta and the New Musical Theories and Fantasies,” occurs over approximately fifteen years and comprises 325 items. Bent, Bretherton, and Drabkin selected twenty-six of these items, including a particularly illuminating letter from Cotta to d’Albert, who intervened on Schenker’s behalf after Cotta initially declined to publish Schenker’s “New Musical Theories and Fanatasies by an Artist.”

Return to text

6. My total of 522 documents is much higher than the 450 that Bent, Bretherton, and Drabkin claim. The likely reason for the discrepancy is that I included diary entries in my count whereas they did not.

Return to text

7. Bent, Bretherton, and Drabkin take care to remind us in the General Introduction that “diaries are as fallible as any other human document; this is particularly so in Schenker’s case, for we know his diaries were written up not daily but typically weekly and sometimes even months later

Return to text

8. Schenker Documents Online provides an extensive profile of Jeanette Schenker.

(http://www.schenkerdocumentsonline.org/profiles/person/entity-000771.html) accessed 22 October 2015.

Return to text

(http://www.schenkerdocumentsonline.org/profiles/person/entity-000771.html) accessed 22 October 2015.

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2015 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Rebecca Flore, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

7179