Review of Anna Zayaruznaya, The Monstrous New Art: Divided Forms in the Late Medieval Motet (Cambridge University Press, 2015)

Justin Lavacek

KEYWORDS: Ars nova, motet, Vitry, Machaut, medieval, text, musicology, disunity

Copyright © 2016 Society for Music Theory

[1] Anna Zayaruznaya’s book, The Monstrous New Art: Divided Forms in the Late Medieval Motet, presents an intriguing new perspective on a relatively small, complex, and much-scrutinized repertoire. The book is an expansion of the concept behind her important 2009 article, which portrays voice crossing in Machaut’s motets as Fortune turning the tables on the usual position of voices, just as in the composer’s poetry she is wont to level kings and raise the ignoble. In The Monstrous New Art, Zayaruznaya expands her purview to ars nova motets generally, and beyond voice crossing to any atypical patterning that effects (audible) divisions in a motet. For the author, “features which seem strange or unusual are places to look deeper rather than anomalies to gloss over” (20) and “the lens through which [she has] chosen to examine this repertory magnifies rifts and fissures, allegorical as well as psychological” (220). Zayaruznaya thus carves out a new subgenre of the ars nova motet that flourished in the half century between Fauvel (1310) and the 1360s, a significant bestiary comprising some twenty out of ninety extant ars nova motets (173). “Monstrous” here are those works whose text(s) treat themes of division and disunity, broadly construed to reference the character of historical people, mythological creatures (chimera, centaur, siren), allegorical figures (Fortune, Love, courtly lady, triune God), objects of piecemeal construction, and more subtly the stratified organization of “bodies” like medieval civil and clerical classes. Her vital connection is made when “motets whose upper voices dwell on a series of fragmented creatures

[2] Zayaruznaya stresses that the relation between hybridity in textual subject matter and musical organization is an abstract one. Ars nova motet composers pursued what she calls the broader congruence of “form-idea relations,” driven by analogy and allegory (18). Zayaruznaya situates this relationship as an “important early chapter in the history of musical hermeneutics” (234) before the more direct mimesis of Renaissance text painting.

[3] The first chapter is devoted to a question upon which the acceptance of the monstrous subgenre is predicated: how can a motet have a body? Zayaruznaya finds ample evidence of this creaturely ontology. Not only do medieval bestiaries align meaning with morphology (21), “medieval music treatises are replete with body parts” (25). We are reminded of familiar analogies like Guido’s hand, Grocheio’s likening of the tenor to a skeleton that gives structure to the whole, the varying note heads of mensural notation, and tails [caudae] tacked on to the end of antiphons.(1) Having established a concern for taxonomy and the proper arrangement of parts, Zayaruznaya brings an eye for division to bear on musical structure, showing in the case studies that follow how composers explored and exploited the new compositional possibilities afforded by an increasingly well-ordered motet genre.(2)

[4] As ars nova composers developed tenor isorhythm, an early form of intrinsically musical structure not based upon a poetic scheme (as in the formes fixes), they experimented with boundaries as a natural process in the very effort of defining them (see 222–25). Because the ars nova motet was an organic whole made up of interdependent parts, it could be conceived of as bodily. And if bodily, anything but the perfect alignment and coordination of all parts can be interpreted as deformity. Matching their potential for hybridity in form, many ars nova motets are also polytextual and speak from (or embody) three unique voices simultaneously. While the upper-voice poetry of many motets serves to amplify and interpret the classical subject of the tenor voice, it may also contradict the tenor, dividing the whole.(3) Exploiting unity as a norm in the greater quantity of non-monstrous motets, motets based upon divided materia could play with that expectation as a means of expressivity; they could distort, subvert, and otherwise comment upon wholeness. As Zayaruznaya observes, “new standards of unification present new opportunities for division” (225).

Figure 1. Fauvel holding court, a familiar example of medieval monstrosity (BnF fonds français 146, fol. 15v )

(click to enlarge)

[5] Some motet texts are straightforward in their descriptions of bifurcated or deformed creatures. Consider the essential example of Fauvel—“the ars nova’s equine Godfather” (100)—a monster who is drawn in manuscript along a spectrum of horse-man: figuring as a centaur, a horse, and a horse-headed man (as in Figure 1). Divided creatures in medieval art, musical and otherwise, were usually negative exempla, examples what not to do, and they require a habitat of normative expectations to flourish (see 94, 175, and 222). The very embodiment of corruption and vice in fourteenth-century France, Fauvel is a low beast raised up by the vicissitudes of Lady Fortune (another monster of disparate body and schemes) to prominence in the royal household. He is depicted with hybrid form because he is a living representation of division; indeed, Fauvel’s very name is an acronym (of sins: Flaterie, Avarice, Vilainie, Variété, Envie, and Lascheté).

[6] As the Roman de Fauvel was interspersed with motets, and the fourteenth-century French mind attuned to allegorical depiction, Fauvel’s hybridity was not only presented visually and narratively, but also musically. Diagnosing abnormality in the disparity between its text and musical organization, Zayaruznaya pins down one particular motet from Fauvel for dissection. With its first-person tenor, whose isoharmonic repeat suggests an ABA setting, the motet Fauvel/Autant m’est embodies the very palindromic thing it names: Fauvel himself (46–52).(4) Indeed, “neither the horse nor those grooming him can tell his head from his ass” (50).

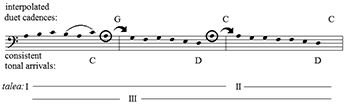

[7] Such corporeal framing of musical structure continues to the present. Hepokoski and Darcy evoke a bodily composition when they speak of the deformation of sonata organization, a form type teeming with monsters and that proffers no textual license to musical disunity.(5) A. B. Marx, too, conceived of the sonata organically, with a bifurcation of masculine and feminine themese that function together interdependently.(6) Hermaphroditic hybridity was included in medieval bestiaries and decried as monstrous in the fourteenth-century ballade Contre les hermaphrodites, by Eustache Dechamps. While a motet that features male/female hybridity may fall under Zayaruznaya’s purview, the subject is not broached by The Monstrous New Art. Machaut’s motet 7 (Lasse! / Ego moriar pro te) is such a specimen nonetheless, with its simultaneous feminine upper voices and masculine tenor.(7) David’s lament in the tenor that he would die for his son, Absalom, prompts easy association with the ubiquitous fin’amor trope of a suitor so burning with desire that he would die for his lady. Such textual hybridity, we now know, often correlates with musical division, and there is much to be found here. Linking duets, which audibly reduce motet 7’s texture, conclude the first three of six taleae (measures 33–39, 71–77, and 109–115 in Schrade’s edition). These three taleae fill only two colores, and the duets at their joints draw attention to the uneven alignment of the motet’s dependent parts. Such a 3:2 isorhythmic ratio in itself is not monstrously uncommon, but the duets also effect tonal hybridity. All three cadence without the leadership of the ostensibly foundational tenor voice because they distend their taleae beyond the chant’s last note. Furthermore, while talea boundaries are an expected place to cadence, not one of the duets’ cadences align with any other cadence in the motet(8).

Example 1. Tonal monstrosity in the tenor of Machaut’s motet 7

(click to enlarge)

[8] This audible accentuation of misaligned and swollen components by the upper-voice pair occurs on top of Machaut’s tonally divisive segmentation of the chant tenor. While his (pre-compositional) isorhythmic plan leaves off the first two taleae on A (circled in Example 1 below), Machaut’s polyphonic setting closes on the prior notes (C and D, respectively). In both cases, he orphans a pitch at the end of a talea that could more naturally begin the following one. And while these initial taleae end on A, their extending duets close on C and G.(9) Talea III ends with a stepwise descent to D, ripe for cadence, but then the third duet spills over this boundary, cascading down another step to conclude the first half of the motet on C (measure 114). Example 1 summarizes the tonal monstrosity in Machaut’s motet 7, wrought through deformational segmentation of the tenor and its polyphonic realization, which resonates abstractly with the hybridity of its texts.

Example 2. Range and Implied modal orientation with the color of Cum Statua/Hugo (Zayaruznaya, example 3.4, p. 115)

(click to enlarge)

[9] In a motet tenor, structural hybridity and uncertain origin can be the bared teeth of a monster. Zayaruznaya’s Example 3.4 characterizes the tenor of Vitry’s motet Hugo/Magister invidie as monstrous by demarcating three zones “differentiated by range and modal orientation” (114–15).(10) Her example shows both bi- and tripartite divisions of the color, analyzed by range and presumed final. Both cases of the bipartite division are problematic because the final makes tritones with salient melodic pitches. Her example is reproduced as Example 2.

[10] If the first bipartite zone (pitches 1–12) is centered on

[11] Jennifer Bain’s (2008) study of multiple tonal centers in Machaut’s secular songs, which is not cited in the present book, nonetheless provides an enriching complement to Zayaruznaya’s musical philology. Bain’s exhaustive appendices tabulate how every polyphonic song of Machaut defines its (body) parts along the formes fixes; then, in cases we may now deem monstrous, shuffles and recontextualizes them. The polyphonic songs are “divided forms” indeed—only about a third of them begin and end on the same sonority—and hunting their texts for monsters may newly frame our interpretation of tonal and textural ingenuity within these fixed forms.

Example 3. Similar motet tenors in Machaut

(click to enlarge)

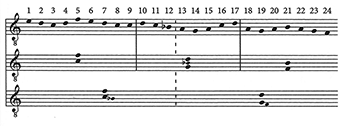

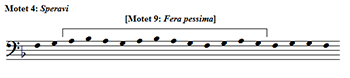

[12] Some motets are monsters not through a derangement of parts, but by the Janus-faced duplicity of them. Zayaruznaya demonstrates how voice crossing can be a musical representation of a textual reference to falsehood (119ff). Returning to Vitry’s Hugo/Magister invidie, the motetus’ second syllable “-go” is elongated to tenor-like duration and sounds lowest in the texture, evoking the common tenor “virgo.” In this case, the “impious” and “perverse” Hugo is posing in the motet as the blameless Virgin Mary (121). With an eye for hunting monstrous quarry, Machaut can be found arranging a comparable deception between his motets 4 (Puis que la douce/Speravi) and 9 (O livoris/Fera pessima).(12) The tenors of these motets are remarkably similar; M9 seems to be an excerpt of M4, as shown in Example 3.(13)

[13] M9 is overtly feral. Its tenor’s “most evil beast” refers to that paragon of monsters, Satan, who is further connoted by Machaut’s upper-voice poetry and arguably embodied by the triplum and tenor lines themselves.(14) The triplum’s introit names Lucifer the font of all pride [superbie], vividly depicting this sin through a lengthy solo, and later describing him as a dragon and a serpent. The serpentine undulations of the tenor melody corroborate this description, animating the beast of the texts. Given how forthright these voices are, the motetus need hardly hint that “the treachery of Iscariot lies hidden within.”(15)

[14] If the tenor of M9 is a beast, then it lurks also in the shadows of M4. There the fera pessima can be seen posing as hope [speravi], both the tenor of M4 and one of three gifts with which Love comforts the suitor in the triplum. Yet in fin’amor tradition, the deified lady is unattainable.(16) Her noble countenance veils a cruel heart and the “hope” of M4 is a sugared tenor.

[15] Zayaruznaya’s new book succeeds in renewing a venerable and familiar body of music. From The Monstrous New Art emerges a lively menagerie of motets, and a needed sense of normativity in the ars nova is more sharply defined by a lack of the disunity she describes. My analyses of Machaut’s motets 7, 4, and 9 above are only a modest demonstration of how her way of framing the fourteenth-century motet’s unique counterpoint of texts and musics can inform and expand our understanding of the period. While undoubtedly a contribution that will bear much fruit among medievalists, The Monstrous New Art is also an important study in the early developments of text-music relations, formal unity, and the ontology of the musical work.

Justin Lavacek

University of North Texas

1155 Union Circle #311367

Denton, TX 76203

Justin.Lavacek@unt.edu

Works Cited

Bain, Jennifer. 2008. “‘Messy Structure’? Multiple Tonal Centers in the Music of Machaut.” Music Theory Spectrum 30 (2): 195–237.

Bent, Margaret. 2003. “Words and Music in Machaut’s Motet 9.” Early Music 31 (3): 363–88.

Brownlee, Kevin. 2002. “La polyphonie textuelle dans le Motet 7 de Machaut: Narcisse, la Rose, et la voix feminine.” In Guillaume de Machaut: 1300–2000. Cerquiglini-Toulet, Jacqueline and Nigel Wilkins, eds., 137–46. Presse de l’Université de Paris–Sorbonne.

Burnham, Scott. 1996. “A. B. Marx and the Gendering of Sonata Form.” In Music Theory in the Age of Romanticism, ed. Ian Bent, 163–86. Cambridge University Press.

Busse Berger, Anna Maria. 2005. Medieval Music and the Art of Memory. University of California Press.

Clark, Alice V. 1999. “New Tenor Sources for Fourteenth-Century Motets.” Plainsong and Medieval Music 8 (2): 107–31.

—————. 1996. “Concordare cum Materia: The Tenor in the Fourteenth-Century Motet.” Ph.D. diss., Princeton University.

Fuller, Sarah. 2011 “Concerning Gendered Discourse in Medieval Music Theory: Was the Semitone “Gendered Feminine?” Music Theory Spectrum 33 (1): 65–89.

—————. 1989. “Modal Tenors and Tonal Orientation in Motets of Guillaume de Machaut.” Current Musicology 45–47 (1989): 199–245.

Hartt, Jared C. 2010. “Tonal and Structural Implications of Isorhythmic Design in Guillaume de Machaut’s Tenors.” Theory and Practice 35: 57–94.

Hepokoski, James. 1994. “Masculine-Feminine.” The Musical Times 135 (1818): 494–99.

Hepokoski, James and Warren Darcy. 2006. Elements of Sonata Theory: Norms, Types, and Deformations in the Late-Eighteenth-Century Sonata. Oxford University Press.

Hoffman, Ruth Cassel. 1989. “The Lady in the Poem: A Shadow Voice.” In Poetics of Love in the Middle Ages: Texts and Contexts. Moshe Lazar and Norris J. Lacy, eds., 227–35. George Mason University Press.

Lavacek, Justin. 2014–15. “Contrapuntal Integrity in the Motets of Machaut.” Intégral 28/29: 125–80.

Leach, Elizabeth Eva. 2011. “A Collegial Colloquy?” Music Theory Spectrum 33 (1): 232–33.

—————. 2006. “Gendering the Semitone, Sexing the Leading Tone: Fourteenth-Century Music Theory and the Directed Progression.” Music Theory Spectrum 28 (1): 1–21.

Robertson, Anne Walters. 2002. Guillaume de Machaut and Reims: Context and Meaning in his Musical Works. Cambridge University Press.

Zayaruznaya, Anna. 2010. “Form and Idea in the Ars Nova Motet.” Ph.D. diss., Harvard University.

—————. 2009. “‘She has a wheel that turns

Footnotes

1. In our own time, Leach 2006 describes gendered semitones and sexed leading tones in this repertory. Although it won SMT’s 2007 Outstanding Publication Award, Leach’s arguments were sharply rebutted in Fuller 2011. Leach’s defense appears in the same issue (Leach 2011).

Return to text

2. Busse Berger 2005 persuasively explores the influence of medieval mnemonic pedagogy on the mental composition of isorhythm and other polyphony.

Return to text

3. A framework for interpreting both textual and tonal interactions among lines of counterpoint in Machaut’s motets, and their influence upon isorhythmic organization, is developed in Lavacek 2014–15.

Return to text

4. Motets are cited here by an incipit of the motetus, following medieval convention, and tenor. Zayaruznaya 2010, 11–32, considers the evolution and ramifications of motet naming conventions in valuable detail. The author herself names motets with the upper voices alone, as the more audible workers of division.

Return to text

5. See Hepokoski and Darcy 2006, 11, for a technical definition of deformation.

Return to text

6. See Hepokoski 1994 for a brief review of the gender controversy and Burnham 1996 for a more detailed discussion.

Return to text

7. Brownlee 2002 interprets both the triplum and motetus as the appropriately dual voice of Echo, who pines hopelessly for the love of Narcissus. His essay notes the manifold gender reversals involved in M7 as Machaut, a male poet, composes a female voice in the typical courtly role of a male. For a brief discussion of the construction of feminine identity in the Middle Ages through the traditionally male reference of the poetic voice, see Hoffman 1989.

Return to text

8. Hartt 2010 is a recent study of how Machaut planned his isorhythmic organization so as to maximally afford descending steps in the tenor through which to cadence each segment.

Return to text

9. The final and most frequent tonal center of motet 7 is D. Fuller (1989, 223–24) discusses tonal ambiguity between D and A while proposing a possible source chant that ultimately closes on G.

Return to text

10. Also finding this tenor an oddity, Clark (1999, 121–24), suggests that it may be partially borrowed and partially newly-composed.

Return to text

11. In an appendix, Zayaruznaya’s edition suggests inflection to

Return to text

12. For an account of M9’s tonal ambiguity, see Fuller 1989, 207–209.

Return to text

13. Yet an exact match for motet 9’s chant tenor exists; it is described by Clark (1996, 26) and Bent (2003, 372).

Return to text

14. Gen. 37:20 and 33. Zayaruznaya (34) reads the tenor as referencing the sin of envy, named explicitly in the motetus’s incipit.

Return to text

15. Translation from Robertson 2002, 308.

Return to text

16. The unattainability of the Lady seems the very engine of Machaut’s vast creative output in the genre.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2016 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Rebecca Flore, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

9252