Review of L. Poundie Burstein and Joseph N. Straus, Concise Introduction to Tonal Harmony (W. W. Norton, 2016)

Mary I. Arlin

KEYWORDS: harmony, analysis, part writing, figured-bass realization, ebook

Copyright © 2016 Society for Music Theory

[1] The past ten years have seen a proliferation of undergraduate music theory textbooks—most of which are revisions of earlier editions—that fall into two categories: those that integrate written work, listening, and ear training, such as The Complete Musician by Steven Laitz or The Musician’s Guide to Theory and Analysis by Jane Clendinning and Elizabeth Marvin, and those devoted solely to tonal harmony such as Revisiting Music Theory by Alfred Blatter, Harmony in Context by Miguel Roig-Francolí, or Harmony and Voice Leading by Edward Aldwell, Carl Schachter, and Allen Cadwallader.

[2] The newest music theory textbook devoted exclusively to tonal harmony is Concise Introduction to Tonal Harmony (hereafter CITH) by L. Poundie Burstein and Joseph N. Straus. The authors’ purpose is made clear in the Preface: “no frills and no nonsense—just the essentials. . . . This is a text that students will be able to read and comprehend” (xiii). Within the 370 pages, the authors succeed in focusing on general underlying principles in a way that is both precise and concise yet without diluting the material or seeming to condescend.

[3] I do not mean to imply that this book is flawless; I do not agree with all the musical and pedagogical choices. The big picture is good, however. For the remainder of this review, I will write more specifically about the book’s content.

Example 1. Contents of Chapter 15

(click to enlarge)

[4] CITH is divided into five parts: Fundamentals (4 chapters), Overview of Harmony and Voice Leading (5 chapters), Diatonic Harmony (16 chapters), Chromatic Harmony (10 chapters), and Form (5 chapters). Each chapter (Example 1) is divided into between two and five sections, some with subheads; each closes with “Points for Review” (a concise chapter summary in list form) and a “Test Yourself” activity. The answers for the “Test Yourself” activity are provided in the back of the textbook, followed by a glossary and an index of musical examples.

[5] CITH is in an attractive format with the main topics in the chapter captioned in orange type; the subheads are in bold face, as are the key terms. Boxed annotations above and below the musical examples draw attention to key features in each example.

[6] For models of correct harmonic usage, the authors have assembled examples from a cross-section of musical styles and genres and from numerous composers not normally included in theory textbooks. Examples by Anna Bon, Fernando Sor, Louis-Claude Daquin, Sophia Dussek, Mauro Giuliani, Stephen Foster, Jean-Joseph Mouret, Louise Reichardt, Étienne Méhul, and Scott Joplin are intermingled with the more widely-known composers. The authors’ examples show the students common part-writing mistakes, with the mistakes highlighted in a colored box and clearly annotated.

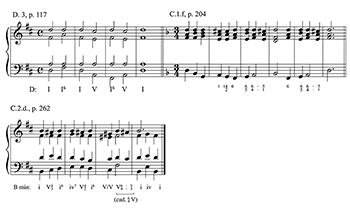

[7] The ebook, included with the textbook, contains links to recordings of all of the examples in the textbook. The student can also click on the bold-faced key terms to reveal definitions. Beginning in Chapter 15, twelve chapters in the ebook have “A Closer Look” link that gives more information on selected topics, e.g. Cadential ![]()

![]()

![]()

[8] The video tutorials elucidate key learning objectives and show the students how to work through the problems in the workbook. The adaptive online quizzes challenge the students to demonstrate the skills they will need to complete the assignments. To complete the online quizzes, the student must answer a specific number of questions to reach a target score. Up to 100 points can be gained or lost on each question, depending on the selected level of confidence, which the student can adjust between questions; bonus points can be earned by answering consecutive questions correctly.

[9] The workbook contains copious exercises of varying length that include a mix of chord spelling, realizing Roman numerals and figured basses, melody harmonization, composition (within specified guidelines), and analysis of musical examples. Some of the writing exercises are to be completed in SATB format, others in keyboard format with the three upper voices in the right hand. The exercises can be completed using Noteflight and submitted to the instructor electronically or they can be submitted in hard copy.

[10] Part 5, the chapters on form (35–39), takes on the Herculean task of introducing sentences and other phrase types, periods and phrase pairs, binary form, ternary, rondo, and sonata forms all within thirty-three pages. Missing from Part 5 is any discussion of motives, texture, harmonic rhythm, variation forms, and contrapuntal genres.

[11] The presentation of binary form is limited to simple binary, rounded binary, and balanced binary, with no mention of sectional and continuous binary forms. In the discussion of sonata form, the authors state: “The secondary theme may present completely new material, or it may be a variant of the primary theme” (365). Haydn’s Piano Sonata in C major, Hob. XVI:10, I, which is monothematic, is used to illustrate an exposition. Granted, the authors were undoubtedly looking for a short example to illustrate the exposition, but as William Caplin (1998) points out, the second key area normally has “a distinct subordinate theme” (97). The exposition of Mozart’s Piano Sonata in A major, K. 333, II is a few measures longer than Haydn’s Piano Sonata in C, but it has two distinct themes, is aesthetically rewarding, structurally clear, and accessible.

[12] The ordering of the text is based on the ordering of these basic chord progressions: I–V–I is expanded first by inversions and by V7 and its inversions, next by the addition of the subdominant (I–IV–V–I) and the substitutions of ii6 and ![]()

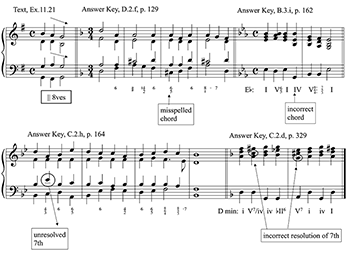

![]()

![]()

![]()

[13] Unfortunately, CITH is marred by problems of all sorts, many of which should have been eliminated in the editing stage. In the discussion of six-four chords in Chapter 23, the authors write: “Other ![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

Example 2

(click to enlarge)

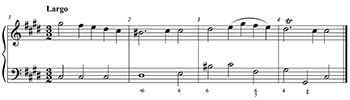

[14] Part Two, “Overview of Harmony and Voice Leading,” concludes with a chapter on species counterpoint (first, second, and fourth). When adding a counterpoint above the cantus firmus, the students are cautioned: “Like the cantus firmus, the counterpoint should have a single melodic climax or high point (which may not be the leading tone)” (94). Unfortunately, this is the one and only reference to melody writing and counterpoint in the text and workbook. The Answer Key contains exercise after exercise in which the melody has no “melodic climax,” and no heed is paid to the outer-voice counterpoint (Example 2). All is not lost, however. When the students are asked to supply a melody above a figured bass in the video for Chapter 12 (![]()

![]()

[15] The text contains statements that are subsequently contradicted in the selected repertoire. For example, the students are advised, “The instability of V7 makes it less well suited to serve as a resting point at a half cadence (HC), however. Accordingly, in basic four-part harmony a half cadence should arrive on V, not V7” (115). Despite this admonition, the authors include an excerpt from Schubert’s German Dances D. 783, no. 13 (Ex. 28.5, 267) in which there is a HC on V7 with no mention whatsoever of the anomaly.

[16] The authors continue, “If V7 were to move to V, the chordal dissonance would not resolve; thus a V7–V progression should be avoided” (116). In Chapter 28 (Ternary and Rondo Forms) in the workbook, the students are asked to label the Roman numerals and cadence types in the Trio (mm. 21–36) of Haydn’s String Quartet op. 20, no. 4, III. The half cadence in mm. 31–32 has a V7 to V progression. In light of their assertion that “a V7–V progression should be avoided,” the authors should have asked a relevant question about the musical effect of Haydn’s choice of a V7–V progression at the cadence.

Example 3

(click to enlarge)

[17] In Chapter 11 the authors write: “a I6–V6 progression is common, providing that the bass leaps down” (124). Example 13.9 (139), which is given as Example 3 below, quotes the opening measures of Handel’s Violin Sonata in E, HWV 373, II, which contains a bass leap up to from .(1) The authors point out the voice exchange of

[18] “Points for Review” in Chapter 12 remind the students: “![]()

![]()

![]()

[19] Performance indications directly affect analysis; yet none of the musical examples in the textbook has a tempo. In the Answer Key, the first musical examples to have a tempo indication are in Chapter 30: Schubert’s “Der Müller und der Bach” (336) and Chopin’s Waltz op. 34, no. 2 (337). Four chapters later a tempo indication is given for Liszt’s “Consolation no. 3” (375); beginning with the last example in Chapter 37 (Brahms, Waltz op. 39, no. 5), all of the remaining musical examples in the Answer Key (chs. 38–39) have tempo indications. Similarly, measure numbers for the repertoire are missing in the textbook until Chapter 39 (Sonata Form) and in the Answer Key until Chapter 34 (Chromatic Modulation, 373).

Example 4

(click to enlarge)

Example 5

(click to enlarge)

[20] The examples in both the textbook and Answer Key (Example 4) contain a maddening number of errors—parallel fifths and octaves, unusual doublings (e.g., doubling a note other than the bass in a ![]()

[21] For me, the authors’ treatment of modulation is the Achilles heel. The authors state, “Applied chords can create brief changes of key, known as tonicizations. A change of key that is lengthier and more substantial, and whose tonic is confirmed by a cadence, is known as a modulation” (257). Then they cite the opening eight measures from the second movement of Haydn’s Symphony no. 94 as an example of a pivot-chord modulation to the dominant that is “confirmed by a cadence in G” (260) in mm. 7–8. As Example 5 shows, the purported modulation in mm. 7–8 is a tonicization, a brief change of key, with a cadence on G. This movement is firmly rooted in C major.

[22] By focusing on “cadence” rather than “long and substantial,” the authors identify the majority of tonicizations at a cadence as modulations. Drawing a firm line between modulations and tonicizations in tonal music is not possible, but identifying a tonicization at the cadence as a modulation gives the students an inaccurate understanding of modulation.

[23] As of this writing, only two chapters of the ebook, with their accompanying video tutorials and online quizzes, were available for perusal. Anna Gawboy is creating the video tutorials and Inessa Bazayev the online quizzes; there are some differences in terminology between the textbook authors and the media authors. For instance, the textbook authors use “time signature”; the video uses “meter signature.” Whereas the text identifies major triads “with just their root,” the video uses CM; minor key tonal centers in the textbook are labeled E min, whereas the video uses Em. These issues aside, the videos are beautifully produced, informative, and visually appealing. To view the videos with an iPad, it must be in vertical position.

[24] The questions for the online quizzes have a mixture of learning levels: application, knowledge, comprehension, and analysis. All the questions are interactive: the students have to drag-and-drop elements from one place to another; find and click a choice or a part of an image (e.g., a chromatic sign); or type an answer to the question. The students receive immediate feedback after every click, drag/drop, or key press, including references to specific pages in the ebook. Although the textbook focuses exclusively on written common-practice harmony and form, some of the online questions use an aural stimulus.

[25] There are audio quality issues in the ebook that need to be resolved. Some of the examples have been created on an acoustic piano, others on an electronic piano. The beginning of the audio for 12.3 has an anticipation that is not in the score. The bass line for 12.5 is unclear, and the opening arpeggiation of 12.6 is missing.

[26] The problems mentioned here should not detract from the overall success of the book, however. Teachers can easily correct errors and respond to the anomalies in class. The chapters in CITH are only a few pages long and can easily be reordered to reflect a different topical sequence. CITH is comprehensive, elegantly written, well planned, and should prove a popular choice for teachers who embrace the flipped classroom: “instruction that used to occur in class is now accessed at home, in advance of class.”(3) With CITH, the music theory classroom can truly become a place to engage in collaborative learning: the teacher can dispense with the “what” and “where” and invoke questions similar to those posed by Michael Rogers (2004, 93–99) to help students “come to understand, from the inside out, why and how a piece of music works” (75).

Mary I. Arlin

School of Music

Ithaca College

953 Danby Road

Ithaca, NY 14850

arlin@ithaca.edu

Works Cited

Aldwell, Edward, Carl Schachter, and Allen Cadwallader. 2011. Harmony and Voice Leading. 4th ed. Cengage Learning.

Blatter, Alfred. 2007. Revisiting Music Theory: A Guide to the Practice. Routledge.

Caplin, William. 1998. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. Oxford University Press.

Clendinning, Jane and Elizabeth Marvin. 2016. The Musician’s Guide to Theory and Analysis. 3rd ed. W.W. Norton.

Duker, Philip, Anna Gawboy, Bryn Hughes, and Kris P. Shaffer. 2015. “Hacking the Music Theory Classroom: Standards-Based Grading, Just-in-Time Teaching, and the Inverted Class.” Music Theory Online 21 (1).

Laitz, Steven G. 2011. The Complete Musician. 3rd ed. Oxford University Press.

Rogers, Michael. 2004. Teaching Music Theory: An Overview of Pedagogical Philosophies. Southern Illinois University Press.

Roig-Francolí, Miguel. 2011. Harmony in Context. 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill.

Tucker, Bill. 2012. “The Flipped Classroom.” Education Next 12 (1): 82–83. http://educationnext.org/the-flipped-classroom/

Footnotes

1. The figured bass on the downbeat of m. 3 is given erroneously as 6/5 in Example 13.9.

Return to text

2. One of the InQuizitive questions (ch. 12) has a bass that leaps up to from .

Return to text

3. Tucker 2012, 82–83. Also, see Duker et. al. 2015.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2016 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason, Managing Editor

Number of visits:

13965