Rethinking Interaction in Jazz Improvisation *

Benjamin Givan

KEYWORDS: jazz, improvisation, interaction, Miles Davis, Horace Silver, Sonny Rollins, Jimmy Smith, Wes Montgomery, Art Blakey, Lee Morgan, Gerry Mulligan

ABSTRACT: In recent years, the notion that “good jazz improvisation is sociable and interactive just like a conversation” (Monson 1996, 84) has become near-conventional wisdom in jazz scholarship. This paper revisits this assumption and considers some cases in which certain sorts of interactions may not always be present or desirable in jazz performance. Three types of improvised interaction are defined: (1) “microinteraction,” which occurs at a very small scale (e.g. participatory discrepancies) and is not specific to jazz; (2) “macrointeraction,” which concerns general levels of musical intensity; and (3) “motivic interaction”—players exchanging identifiable motivic figures—which is a chief concern of today’s jazz researchers. Further, motivic interaction can be either dialogic, when two or more musicians interact with one another, or monologic, when one player pursues a given musical strategy and others respond but the first player does not reciprocate (as in “call and response”). The paper concludes by briefly considering some of the reasons for, and implications of, the emergence of interaction-oriented jazz scholarship during the late twentieth century.

Copyright © 2016 Society for Music Theory

[1] In the wake of Paul Berliner’s and Ingrid Monson’s landmark interview-based research of the mid-1990s, the notion that “good jazz improvisation is sociable and interactive just like a conversation” (Monson 1996, 84) has become near-conventional wisdom in the field of jazz studies.(1) Numerous other scholars have since demonstrated conclusively that spontaneous ensemble interaction is a prominent element of jazz, and in so doing have greatly enrichened our knowledge and understanding of this signal Afrodiasporic art form as both a musical and a social practice.(2) Some have even gone so far as to characterize jazz as “a music that demands interaction” (Doffman 2011, 213); it has been said that dialogical interplay between participants is “fundamental and always present” within the idiom (Szwed 2000, 65), that it is “continual” (Gratier 2008, 80) and “constant throughout a performance” (Iyer 2004, 394), and that “if [it] doesn’t happen, it’s not good jazz” (Monson 1996, 84). Yet the concept of interaction in jazz nevertheless remains somewhat undertheorized. More still needs to be said about what, exactly, it is, and about the various roles it plays in everyday performance practice.

[2] For the purposes of this discussion, I define musical interaction as involving one or more members of an ensemble improvising spontaneously in response to what other participants are playing.(3) Improvisation, in itself, need not necessarily be interactive. But interaction, as defined here, occurs extemporaneously, rather than being predetermined in the manner of a scripted conversation or, say, the contrapuntal interplay in a fugal Baroque composition.(4) Musicians’ statements and performance practices suggest that interaction, so conceived, can take a variety of different forms, some of which are ubiquitous in most any live performed music, including jazz, while others—including modes of interaction that are considered highly characteristic of jazz—are far from omnipresent in this particular idiom and can even at times be undesirable. If we can better understand when and why jazz musicians sometimes claim to prefer noninteractive performance conditions, we will be able to recognize more clearly the nature and limits of improvisatory interaction itself, as well as to differentiate more precisely between some of its various manifestations. We will also be positioned to briefly step back and consider why interaction emerged as a major focus of jazz scholarship at a particular point in time, and this trend’s consequences for how jazz is viewed within the academy today.

[3] Jazz musicians do not always regard ensemble interaction as essential. For one thing, the idiom has a long tradition of unaccompanied solo playing. Pianist Billy Taylor (1921–2010) once observed that:

Many keyboard players enjoy improvising alone because solo playing gives them the freedom to organize all the elements of their music completely on their own terms. When playing solo, they do not have to react or respond to musical phrases, harmonic tensions, or rhythmic patterns provided by other musicians, as they do in jazz groups. Sometimes this leads to self-indulgent music which is boring and formless, but on other occasions the player is able to create music which is meaningful to many listeners on many different levels (1982, 23).(5)

Needless to say, jazz is a diverse art form, and Taylor plainly depicts solo playing as an exception to the norm. Moreover, when playing unaccompanied, many jazz pianists tend to mimic the idiom’s typical interactive group format by enacting several ensemble roles concurrently. Taylor himself might treat a rubato unaccompanied ballad as an opportunity for unfettered pianistic self-expression, but when playing up-tempo alone he was more likely to support his right hand’s horn-like melodic lines with left-hand stride patterns, walking tenths, or chordal bebop comping, all strategies embodying the dynamics of a multi-person rhythm section.(6)

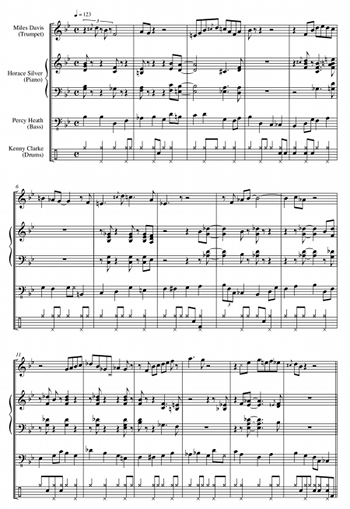

Example 1. Miles Davis, “Doxy” (0:32)

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 2. Horace Silver, “Doxy” (3:10)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[4] Unaccompanied playing, as described by Taylor, can of course be considered merely an exceptional—though quite widespread—limit case within a prevailing interactive jazz aesthetic. In ensembles, real-time improvised interplay is common, as many studies have demonstrated. But even among jazz players who directly cite the importance of collective ensemble interaction, musical practices vary considerably. Pianist and composer Horace Silver (1927–2014) described a good rhythm section as one that “really hit[s] it together” and “make[s] the horn players better” (Lyons 1983, 124). Yet it is not self-evident how, precisely, he might actualize this sort of collaborative, altruistic performance ethic, and whether it necessarily involves interactive techniques. While accompanying trumpeter Miles Davis’s first solo chorus on a 1954 recording of “Doxy”(7) (transcribed in Example 1), Silver undoubtedly coordinates temporally and stylistically with bassist Percy Heath and drummer Kenny “Klook” Clarke to create an effective “groove”(8) texture, but unambiguous moments or passages of interaction between the players are otherwise not easy to discern. The pianist himself said that synchronization and “groove” were aesthetic desiderata when working with this particular rhythm section, recalling that “Percy Heath told me to listen carefully to Klook’s cymbal beat so that I would be turned on and be able to groove with him” (Silver 2006, 60). He thought a jazz rhythm section’s primary obligation was to support a soloist with an inspiring, idiomatically appropriate musical environment—“we’ve got to raise our hands and uplift them to the sky” (Lyons 1983, 124); “when everything is cooking, the rhythm section is cohesive, everything is smooth,

[5] In some instances, jazz musicians have expressly stated that interactive musical processes can at times be undesirable or even creative hindrances. Davis (1926–91) recalled that, while he was playing in alto saxophonist Charlie Parker’s Quintet during the 1940s, Parker “used to turn the rhythm section around. Like we’d be playing a blues, and Bird [i.e., Parker] would start on the eleventh bar, and as the rhythm section stayed where they were and Bird played where he was it sounded as if the rhythm section was on one and three instead of two and four. Every time that would happen, [drummer] Max Roach used to scream at [pianist] Duke Jordan not to follow Bird, but to stay where he was. Then, eventually it came round as Bird had planned and we were together again” (Hentoff 1959, 90, quoted in Carr 1998, 35–36). By Davis’s account, such performances were most likely to turn out successfully if the rhythm section steadfastly adhered to the predetermined meter and harmonies without directly responding to Parker’s rhythmically complex solo lines—by, in effect, limiting their interaction with the saxophonist in certain crucial respects, so as not to become distracted or confused.

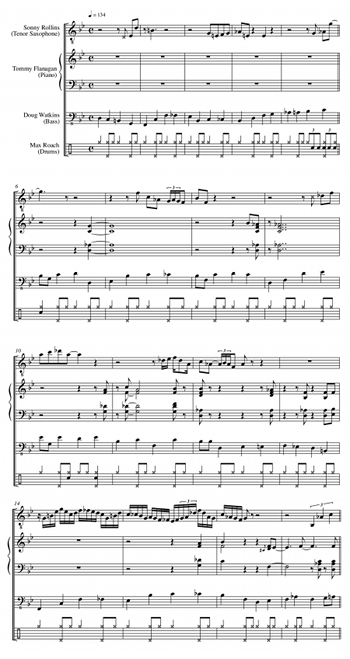

[6] Soloists, too, sometimes prefer that rhythm sections not interact much with the spotlighted individual improviser. “I’ve always thought that I want to have a steady bass player and a steady rhythm section,” reflects tenor saxophonist Sonny Rollins (b. 1930). “When I got those guys to just play steady, then I could play more abstractly.

[7] To be sure, the foregoing anecdotes tell only part of the story, and one reason the concept of musical interaction has proven so interpretatively fruitful is that it can be, and has been, applied to a much broader variety of jazz performance techniques than those mentioned so far. For the sake of precision, I find it helpful to distinguish between three different kinds of interaction which, though neither discrete nor exhaustive, all commonly occur during group performances in many musical idioms, including jazz. I call the first of these “microinteraction.”(13) Microinteraction takes place at a very fine level of musical detail, too small in scale to be quantified by standard Western notation, and includes such phenomena as the tiny adjustments in tempo, dynamics, pitch, and articulation that musicians make while playing together.(14) In any idiom, microinteraction is essential for live ensemble music making (Clayton 2013, 34)—Nicholas Cook notes that classical string quartet players interact spontaneously while collectively negotiating the musical parameters that their scores do not dictate: “the players listen to one another, each accomodating his or her intonation to the others’” (2013, 235),(15) and likewise “each is continuously

Example 3a. Wayne Shorter, “No Blues” (3:27)

Example 3b. Wayne Shorter, “No Blues” (4:40)

Example 3c. Wayne Shorter, “No Blues” (8:40)

[8] The Miles Davis Quintet engaged in some unusually tangible temporal microinteraction during some live performances that were recorded in late 1965 at the Plugged Nickel in Chicago. On a rendition of “No Blues,”(18) tenor saxophonist Wayne Shorter (b. 1933) begins his solo at a tempo of approximately quarter note = 180, so that his first twelve-bar blues chorus spans more than fifteen seconds (track time 3:27; Example 3a).(19) Gradually the ensemble—spurred by the rhythm section of pianist Herbie Hancock, bassist Ron Carter, and drummer Tony Williams—accelerates its tempo until, by Shorter’s ninth chorus, they together reach a pace of roughly quarter note = 336, with twelve bars elapsing in under nine seconds (4:58; Example 3b). Their tempo then starts to slow incrementally, subsiding to quarter note = 140 as Shorter’s solo ends (9:12; Example 3c). Clearly such steady, yet extreme, ensemble tempo changes require continual microinteractive synchronization, with all members of the group listening attentively to one another while adjusting their tempo at a rate that is almost imperceptible from each beat to the next (Rasch 1988; Goebel and Palmer 2009).

Example 4. Duke Ellington, “Ready Go!” (15:14)

[9] The more typical, everyday modes of temporal synchronization that jazz ensembles undertake when playing at more-or-less steady tempos can often be much harder for listeners to hear; as pianist Vijay Iyer has noted, these processes are most tangible to performers themselves, by means of embodied—rather than purely auditory—perception (2002, 391–407).(20) Indeed, players may not always be consciously aware of such processes while they are occuring (Schiavio and Høffding 2015). But sometimes even these subtler microinteractions can be quite perceptible to nonparticipants as well as performers. The Duke Ellington Orchestra’s rhythm section opens a 1959 recording of the uptempo blues “Ready Go!”(21) with bassist Jimmy Woode quite audibly playing at a markedly slower tempo (approximately quarter note = 190) than pianist Ellington and drummer Sam Woodyard (15:14; Example 4).(22) At the fifth bar (15:19), Woode begins to gather speed, and by measure 7 (15:21) Ellington’s keyboard comping is decisively pushing the tempo, with Woodyard closely following suit (15:22). By measures 9–10 all three players have begun to synchronize at a faster pace (15:24). As they reach the top of the second chorus (15:28), Woodyard initiates another slight tempo acceleration, shifting from his hi-hat to the ride cymbal, and the three players settle in at a pace of around quarter note = 224, joined by tenor saxophone soloist Paul Gonsalves.

Example 5a. Dizzy Gillespie, “Montreux Blues” (4:27)

Example 5b. Dizzy Gillespie, “Montreux Blues” (5:15)

Example 5c. Dizzy Gillespie, “Montreux Blues” (6:50)

[10] Another type of musical interaction, which I refer to as “macrointeraction,”(23) involves the broad sorts of collective coordination whereby improvising musicians play in unified (or at least compatible) stylistic idioms (Gratier 2008, 88) and at mutually coherent intensity levels.(24) For instance, if one ensemble member, mid-performance, starts playing louder, or with shorter rhythmic values, or with increasingly dissonant harmonies, others may follow suit by reinforcing, complementing, or otherwise accomodating this general musical strategy. Macrointeraction occurs quite demonstratively on “Montreux Blues,” a live 1975 recording featuring three leading jazz trumpeters: Roy Eldridge, Clark Terry, and Dizzy Gillespie.(25) As Gillespie (1917–93) begins his solo (4:27; Example 5a), pianist Oscar Peterson and drummer Louie Bellson drop out, leaving the trumpeter to “stroll,” with only bassist Niels-Henning Ørsted Pedersen accompanying, for his first five choruses. Peterson and Bellson then re-enter (5:25; Example 5b), whereupon the music’s energy gradually rises, with various fluctations, over the course of the next six or seven choruses, at which point Terry and Eldridge start riffing behind the soloist (6:56; Example 5c), ratcheting up the intensity level still further. According to Peterson (1925–2007), Gillespie habitually favored this sort of macrointeractive trajectory: “Dizzy loved brute force behind him when he was ready for it; however, he did not like to be forced down into it, preferring instead to have a few choruses of lighter rhythmic involvement, which allowed him to create his flights of linear fancy (many times with a mute) and then open up the floodgates of rhythmic impetus on the listener” (Peterson 2002, 213–14).(26) Affirming Peterson’s tacet restraint during the solo’s opening choruses, Gillespie himself remembered that, during his early days as a bebop innovator during the 1940s, he and other horn players often wanted “a piano player to stay outta the way” rather than to play “leading chords” that more decisively articulated a tune’s rhythms or harmonies (Gillespie 1979, 206–7).(27)

Example 6. Miles Davis, “Straight No Chaser” (3:40)

(click to enlarge and listen)

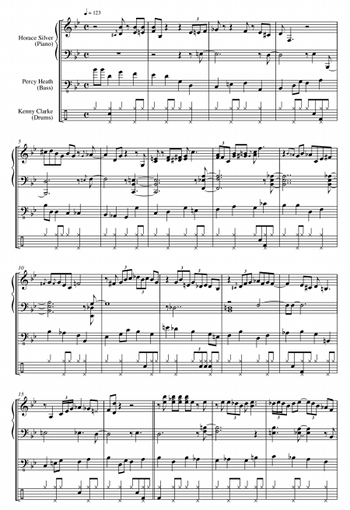

Example 7. Sonny Rollins, “Blue 7” (0:58)

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 8. Sonny Rollins, “Sonny Boy” (5:40)

[11] A third type of musical interplay, which I term “motivic interaction” (following Waters 2011, 57–59; see also Berliner 1994, 368–86), has in recent times drawn considerable attention from jazz scholars. It involves one musician playing a perceptible figure or gesture and others responding with gestures of their own;(28) when improvised in the moment, these sorts of dialogic exchanges clearly manifest real-time social communication. (Naturally, unless participants are available to provide corroborating testimony, external observers can do no more than impute intentionality to such gestural interactions based on evidence such as their temporal proximity and stylistic improbability (Meyer 1973, 73–74); without firsthand verification, we can only conjecture as to whether a given musician conciously meant to do one thing or another.) A fairly plausible instance occurs toward the end of Miles Davis’s solo on a 1958 studio recording of “Straight No Chaser,”(29) transcribed in Example 6. At measure 4 of the excerpt, as the trumpeter pauses between phrases, pianist Red Garland assertively interjects three six- or seven-note chords whose uppermost notes are F5,

[12] Spontaneous motivic interaction in jazz ensembles can often be much subtler than this, though; it may involve as little as echoing a single pitch or fleeting rhythmic pattern. Pianist Tommy Flanagan (1930–2001) provides several successive illustrations with his initial accompanimental chords on saxophonist Sonny Rollins’s 1956 recording “Blue 7”—a track analyzed in a widely read essay by Gunther Schuller (1958).(31) As transcribed in Example 7, Rollins begins his second chorus (measures 5–6) with a three-note melodic figure that ascends by a semitone and then a major seventh, G3–

[13] Motivic interactive responses need not be as directly imitative as Flanagan’s; they can instead complement or even be in tension with other performers’ musical gestures.(34) Herbie Hancock (b. 1940) recalls that, while playing in Davis’s rhythm section during the mid-1960s, he became aware of “the kind of sixth sense that Tony [Williams] had of what Miles might play, or what Tony chose to do to respond to the previous moment. Even when he chose to play something kind of against a rhythm that Miles was playing, it just seemed to fit in the perfect place” (Siegel 1997).(35) Some players consider complementary or oppositional interaction to be more effective than duplicative musical reinforcement: vocalist Dee Dee Bridgewater (b. 1950) tells of feeling creatively constrained by a piano accompanist who tended to anticipate or double too many of her sung phrases (Davis 2005, 51).

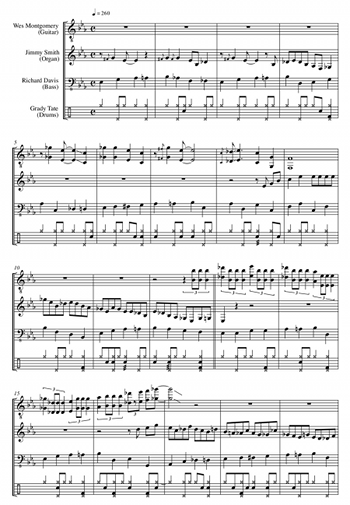

Example 9. Jimmy Smith and Wes Montgomery, “Down by the Riverside” (7:53)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[14] In any given collectively improvised performance, all three types of interaction—micro-, macro-, and motivic—may happen simultaneously.(36) Although each can occur as a two-way dialogic process, they can all just as easily be monologic, with one player pursuing a given musical strategy and another responding, but without the first reciprocating. Call-and-response interplay often exhibits this sort of asymmetrical interpersonal dynamic: one musician leads and another follows.(37) Organist Jimmy Smith (1925–2005) and guitarist Wes Montgomery (1923–68) illustrate while trading fours on their 1966 recording of “Down By the Riverside,”(38) transcribed in Example 9. What is more, they switch their responsorial roles midway through the passage. During their first chorus-and-a-half, Montgomery responds to Smith, imitating or transforming the organist’s motives or figuration: in measures 5–8 the guitarist modifies a riff that Smith introduced in measures 1–4, and in measures 13–16 he picks up on the minor-pentatonicism of Smith’s immediately preceding figure.(39) But then, in measures 17–20, the organist plays an ornate, highly chromatic stream of eighth-notes, upping the interactive ante, because such complex chromaticism is much harder to execute at high speed on a guitar than on a keyboard instrument, let alone to replicate on the fly.(40) Rather than try to replicate this complex figuration, Montgomery answers with a diatonicized version of Smith’s intricate passage—like the organist, he outlines a descending sequence of broken thirds, but he does so while adhering entirely to notes of the

[15] As the next chorus begins (measure 25), Smith imitates Montgomery’s broken thirds, reversing the musicians’ preceding interactive roles. The guitarist takes the initiative thereafter. At measures 29–32 he quotes Red Garland’s composition “Blues by Five,” and Smith replies with a developmental passage springing from the same motivic pattern (measure 32); Montgomery then starts the next chorus with a short repetitive riff (measures 37–40) that the organist again replicates, with drummer Grady Tate joining in the interplay by reinforcing their syncopated accents with his bass or snare drum at two-bar intervals (measures 38, 40, and 42).(41) The remaining sixteen measures (measures 45–60) consist of Montgomery and Smith passing back and forth a descending arpeggiated melodic pattern. Only during this final passage and at the earlier fleeting moment when the call-and-response relationship reverses (measures 21–29) are they both concurrently interacting motivically with each other; elsewhere either one or the other is clearly taking an initiating role. Naturally, the initiating player could be said to be interacting motivically in the sense that he may expect a “response” to his “calls,” but even so, the relationship would not be symmetrical.(42)

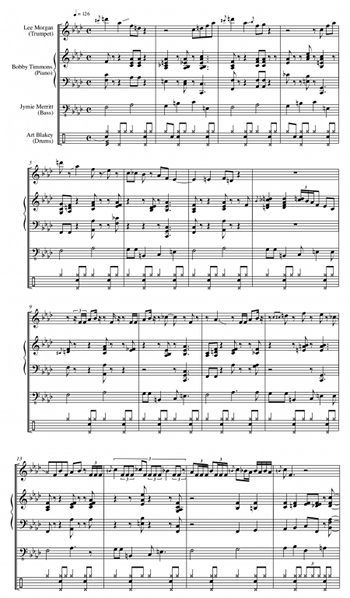

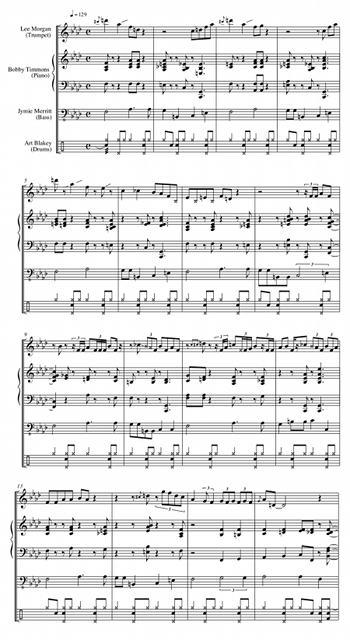

Example 10a. Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, “Moanin’ ” (0:59), Master take

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 10b. Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, “Moanin’ ” (0:59), Alternate take

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 11. Gerry Mulligan, “Bernie’s Tune” (0:37)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[16] Whereas microinteraction is necessary in any successful live group performance and macrointeraction is a straightforward precondition for competent collective improvisation, motivic interaction is only intermittently present in jazz. The opening of trumpeter Lee Morgan’s 1958 solo on “Moanin’,”(43) recorded with Art Blakey’s Jazz Messengers, offers a clear-cut illustration, redolent of the above-cited remarks of Rollins, Donaldson, Lacy, and others. “Moanin’ ” was one of the Jazz Messengers’ greatest popular successes; Monson describes the trumpet solo as “just the kind of exuberant, bluesy playing that has earned Morgan [1938–72] the reputation of being the quintessential hard bopper and the absolute embodiment of ‘badness’ ” (2007, 76).(44) Moreover, Morgan crafted his solo fairly consistently each time the band played the tune, both in live performances and on the alternate and master studio takes, excerpts of which are transcribed in Examples 10a and 10b (McMillan 2008, 87–88). The many similarities between the two takes suggest that, though the players all certainly engage in micro- and macrointeraction, not much spontaneous motivic interaction takes place. The rhythm section lays down a groove and articulates the music’s harmonies and formal structure, but for the most part bassist Jymie Merritt and drummer Art Blakey do not directly respond motivically to Morgan’s melodic line nor to each other. In fact, aside from microinteractive alterations, Blakey executes his backbeat pattern almost identically from each measure to the next throughout both of the transcribed passages. Bobby Timmons’s piano comping engages antiphonally with the trumpeter’s phrases, though it is probably somewhat predetermined rather than spontaneously interactive, given that its rhythmic profile is quite similar in both renditions. Morgan, whose solo varies the most between the two versions despite its stable overall trajectory, could be interpreted as interacting with the rhythm section at a macro level, yet he does not respond motivically to the other players in any overt unequivocal way. Within these excerpts from “Moanin’,” the musicians mutually coordinate temporally, dynamically, and stylistically on the whole, but otherwise execute largely independent defined roles (see also Rinzler 1988, 156; and Love 2016, 71). In perhaps the most memorable moment from one of the most famous performances in postwar recorded jazz, there is almost no spontaneous motivic interaction at all.

[17] To be sure, the opening of Morgan’s solo is atypical in that it is much more predetermined than most postwar jazz improvisations. Ordinarily, mainstream post-bop ensemble performances involve sporadic episodes of motivic interaction interspersed within passages, sometimes quite lengthy, where musicians focus on fulfilling individual roles, adhering to a predetermined formal roadmap, staying rhythmically coordinated, and providing one another with a mutually agreeable, effective macrointeractive playing environment. Consider the Gerry Mulligan Quartet’s 1952 rendition of “Bernie’s Tune,”(45) which is transcribed, except for its opening and closing head statements, in Example 11. Collective interaction was certainly an element of the Quartet’s aesthetic: bassist Bob Whitlock spoke of the players as “musical conversationalist[s]” (Myers 2012), and drummer Chico Hamilton emphasized that all four musicians contributed significantly to the ensemble’s distinctive sound (Panken 2013). Yet at the same time, baritone saxophonist Mulligan streamlined the rhythm section’s accompanimental texture by eliminating the piano, which was customary at the time, and by asking Hamilton to use a pared-down drum kit; his aim was to allow himself and trumpeter Chet Baker greater improvisational latitude by reducing ensemble elements that he felt could potentially be intrusive or confining (Goldberg 1965, 9–10)?>, 27–28).(46)

[18] “Bernie’s Tune” exhibits only occasional moments of unequivocal motivic interaction. Toward the end of Mulligan’s solo, in measures 26–28, Hamilton responds with alacrity to the saxophonist’s fragmentary melodic gestures by interjecting short, incisive drum fills. Later on, at measures 66–67, when Mulligan initiates a chorus of polyphonic melodic activity by both horn players, Baker answers at measure 68 by echoing and then manipulating the leader’s incipit motive (two eighth notes and a quarter note, ascending stepwise).(47) Much of the ensuing macrointeractive texture springs motivically from this initial antiphonal exchange, with Mulligan and Baker concurrently developing similar melodic patterns, yet there are few, if any, unequivocal points of additional motivic interaction between them. Moreover, throughout the preceding separate trumpet and saxophone solo choruses, all four musicians tend mainly to treat their musical roles as functionally complementary but without much motivic interplay—just as Blakey’s Messengers do while accompanying Morgan.

[19] The musical evidence and players’ comments adduced here suggest that it is not uncommon to find jazz ensembles engaging in little or no motivic interaction; in such cases, spontaneous interplay is instead limited to the sorts of micro- and macrointeraction that can be found in almost any live group performance of any musical idiom (Gratier 2008, 82). This certainly does not mean that motivic interaction is not a common, prominent, and fundamental element of much jazz. But it at least raises questions about why theories of interaction in jazz emerged at a particular historical moment in music research. Although a thorough consideration of the various related intellectual trends and institutional changes would be beyond this essay’s scope, a few brief observations are in order.

[20] At least as long ago as the 1930s and ’40s, a number of influential critics identified spontaneous collective creativity as one of jazz’s cardinal traits while also concurrently characterizing the music’s social function as liberatory and egalitarian (Panassié 1936, 35; Goffin 1944, 222; Finkelstein 1948, 238). Before long, certain writers began drawing direct connections between these coexisting structural principles and cultural meanings, arguing that jazz musically exemplified human freedom and social equality. For Hugues Panassié, “the beauty of jazz music” was to be found neither in “the melodic quality of the solos [nor] the architecture of an arrangement,”(48) but rather in their collective “groove,”(49) whose tempo depends on ensemble members’ microinteractive coordination (1944, 46–47; discussed in Perchard 2011b, 36). And for Rudi Blesh, jazz performances were characterized by “profoundly interacting” rhythmic and melodic elements (1946, 30), representing “a conversation of people, all talking about the same thing” (105; quoted in Gennari 2006, 135) that, in turn, “sounds a summons to free, communal, creative living” (4). During the immediate postwar era, the literary scholar and historian Marshall Stearns, then one of jazz’s most prominent advocates, described the music as an “individual expression

[21] Over the course of the following decades, the notion that jazz exemplified non-hierarchical, collaborative social ideals became increasingly widespread.(51) In U.S. political discourse, the idiom was regularly cited as an emblem of American democracy (“H. Con. Res. 57” [1987] 1999).(52) In the private economic sector, it was routinely extolled as an instructive model for a relatively unregimented, collaborative corporate structure—illustrating the sort of “field for interaction” (Bastien and Hostager 1998, 598) that business organizations might emulate.(53) All in all, by the early 1990s it had become a commonplace that jazz improvisation embodied principles of individual freedom, equality, collective co-operation, and spontaneity, a view elegantly encapsulated by the theory of musical interaction, with its attendant metaphor of performance as dialogue or conversation.(54)

[22] Meanwhile, within late-twentieth-century academia, theories of musical interaction were linked to several key intellectual developments. About three decades ago, jazz studies was starting to flower as a research field at more or less the same time that Western art music began to be subjected to increasingly stringent political critiques, its immanent values cast as markedly hierarchical (Ake 2016, 23).(55) During the same period, a number of influential academic literary critics were formulating new, Afrodiasporically grounded theories that construed aesthetic meaning in terms of the social conventions of conversational interaction (Baker 1984; Napier 2000); Henry Louis Gates, Jr., in particular, demonstrated how such perspectives could be productively applied to jazz (1988, 63–64, 104–5), throwing down a gauntlet that was adroitly taken up by music scholars such as Walser (1993) and Monson (1994 and 1996).(56) Interaction-oriented conceptual frameworks thus cleared new disciplinary space for jazz research by providing an illuminating interpretative toolkit that was geared toward the dialogical aesthetics of black American culture and methodologically independent from traditional approaches to Western classical music (Michaelsen 2013a, 11–12 and 25). What is more, interaction-based theories of jazz, in effect, one-upped an earlier generation of postwar formalist critics who had contended that jazz was classical music’s equal as a legitimate object of serious inquiry:(57) when viewed in terms of ensemble interaction, jazz implicitly emerged as politically and morally superior to Western art music insofar as it more fully expressed egalitarian or collaborative values such as respect, trust, deference, and altruism. These qualities came most clearly into focus when analytical attention was shifted away from exclusive focus on the individual soloist, which had typically been formalists’ main concern, and took into consideration the rhythm section’s collective role (Monson 1996, 1).(58)

[23] Interaction-focused perspectives on jazz have, if anything, gained still more currency in the early twenty-first century’s sociopolitical climate of flux, disruption, and instability.(59) With the rise of a collectivist popular ideology privileging “the wisdom of crowds” (Surowiecki 2004; Howe 2008) over individuals’ independent knowledge and expertise, jazz—and musical improvisation generally—has emerged as an empowering metaphor for humanity’s ability to solve problems through spontaneous, diffusely organized communal action. In a recent book devoted to the politics of free jazz and experimental music, Daniel Fischlin, Ajay Heble, and George Lipsitz contend that “improvisation functions

[24] It is also worth recognizing that academic jazz studies’ increased focus on musical interactivity has occurred concurrently with what George E. Lewis calls “the mainstreaming of interactivity as a consumer product” geared toward “information storage and retrieval strategies that late capitalism has found useful in its encounter with new media” (2009, 462).(63) Lewis may well be justified in arguing that “strong interactivity,” exemplified by the comparatively autonomous, idiosyncratic dimension of humanly improvised performance, can potentially counteract such commercial strategies (460–62). Nevertheless, music scholars’ discursive terms do not signify in a disciplinary vacuum; for all that interactive aspects of jazz improvisation have drawn attention by virtue of their inherent interpretative utility and positive sociopolitical value, their intrinsic appeal has likely been heightened because similar terms and concepts have been widely promulgated by corporations in society at large.(64)

[25] Interaction’s role in jazz may additionally have been somewhat overstated because overly broad generalizations have been drawn from unrepresentative case studies. Interaction-oriented studies have largely focused on players whose careers began since the 1940s—above all, practitioners of the subidioms loosely known as bebop, hard bop, free jazz, and their more recent offshoots.(65) (Jazz of the 1960s has an especially visible presence in recent scholarship (Solis 2006, 332, 349).)(66) Although these postwar subidioms’ degree of interactivity can greatly vary, as the preceding pages have shown, they are not necessarily typical of jazz in general—they tend to feature more motivic interaction than do some of jazz’s diverse performance practices (Michaelsen 2013a, vii, 27). The “interactively created African American jazz ideal,” Tom Perchard has recently argued, is essentially “an abstraction of post-bebop practice sometimes made metonym for a much longer, and much more variable ‘jazz tradition’ ” (2011a, 89). Interaction is, to be sure, often present in earlier jazz styles—it certainly occurs in New Orleans-style polyphony, when improvised.(67) But a great deal of pre-World-War II jazz, especially music from the swing era, placed less emphasis on spontaneous interplay and, at times, heavily emphasized composition and arrangement.(68)

[26] At any rate, by privileging postwar jazz styles as a research focus, scholars of interaction are in accord with the longstanding textbook narrative of jazz history that depicts the music as evolving from vernacular and commercial origins into a structurally complex elite music whose first artistic pinnacle was bebop (DeVeaux 1998; Gendron 2002).(69) This may not be coincidental. The sorts of motivic recurrence and complementation that are today frequently seen as jazz’s characteristic interactive social processes are often the very same features that formalist analysts have historically valorized, from a more abstract standpoint, as aspects of stuctural coherence, except that formalists have tended to focus on such strategies as pursued by a single improviser rather than as shared dialogically between multiple players. (Montgomery and Smith’s call-and-response interplay on “Down by the Riverside,” for example, could easily be heard as a succession of formal motivic transformations as well as a ludic conversational exchange.(70)) Both analytically- and ethnographically-oriented scholars have regarded bebop and post-bebop styles as the principal stylistic loci of these sorts of sociomusical practices. So for all that studies of motivic interaction ostensibly offer an alternative to formalist musical analysis (Monson 1996, 135–36), they have done so largely within the parameters of the prevailing jazz canon—a canon grounded in formalist conceptions of aesthetic progress.(71) If anything, their purview has been somewhat more limited.

[27] There is no question that theories of improvisational interaction have been powerful, illuminating tools for understanding jazz’s musical principles and their social meanings. But if we overemphasize interaction’s role in jazz, drawing attention away from contrasting performance techniques, the inevitable if unintended result is an overly narrow and homogeneous conception of the idiom.(72) For beyond Blakey’s “Moanin’ ” or Mulligan’s “Bernie’s Tune”—and beyond the post-bop styles that have been this article’s main focus—lies a wealth of music and a host of players, all squarely within the conventionally accepted jazz tradition, for whom motivic interaction has not always been an overriding musical concern. Jazz encompasses an unaccompanied piano school from the Harlem stride of James P. Johnson through the hyperindividualistic virtuosity of Art Tatum to the untrammeled invention of Cecil Taylor and Keith Jarrett.(73) Composers and arrangers from Jelly Roll Morton, Duke Ellington, and Fletcher Henderson to Gil Evans, Thad Jones, Carla Bley, and Maria Schneider all rank among the idiom’s most influential innovators.(74) The improvised melodies of early soloists such as Louis Armstrong, Sidney Bechet, and Coleman Hawkins do not, in many instances, tend to respond motivically to accompanying musicians(75)—Hawkins was in fact renowned for his ability to improvise brilliantly with minimal attention to his fellow ensemble members (Schuller 1989, 433; discussed in DeVeaux 1997, 268). And contemporary smooth jazz often emphasizes a combination of minimally-embellished melodies with fixed arrangements and recording production techniques typical of pop music, rather than improvisatory interaction (Washburne 2004, 127–37; Carson 2008, 2–5). These musics and musicians have remained enduring presences in jazz scholarship in spite of the rise of interaction theories—and not because such theories have, to date, shed significant light on them. Only when we recognize the limits of interaction theories, along with their strengths, and only once we acknowledge their disciplinary context and motivating ideologies, do we truly open our eyes to jazz’s infinite variety.

[28] “Jazz,” Langston Hughes once wrote, “is a great big sea. It washes up all kinds of fish and shells and spume and waves with a steady old beat, or off-beat” (1958, 493). If this extraordinarily pluralistic musical idiom can be sociably conversational, it can also just as easily be a medium for assertive individualistic self-expression.(76) It may be egalitarian and collaborative, yet also occasionally competitive, combative, and adversarial. It can require amiable co-operation, but can equally depend on inequitably divided responsibilities.(77) And however much we may idealize the jazz ensemble as embodying democratic values, we should not forget that, socially and musically, many jazz bands have in reality functioned far more hierarchically than collaboratively.(78) Jazz is, if anything, an ocean of complexities and contradictions, and to recognize these is only to appreciate more deeply its makers’ creative breadth and vision.

Benjamin Givan

Skidmore College

Music Department

815 North Broadway

Saratoga Springs, NY 12866

bgivan@skidmore.edu

Works Cited

Ake, David. 2016. “On the Ethics of Teaching ‘Jazz’ (and ‘America’s Classical Music,’ and ‘BAM,’ and ‘Improvisational Music,’ and

Al-Zand, Karim. 2005. “Improvisation as Continually Juggled Priorities: Julian ‘Cannonball’ Adderley’s ‘Straight, No Chaser.’ ” Journal of Music Theory 49 (2): 209–39.

Ashe, Bertram D. 1999. “On the Jazz Musician’s Love/Hate Relationship with the Audience.” In Signifyin(g), Sanctifyin’, and Slam Dunking: A Reader in African-American Expressive Culture, edited by Gena Dagel Caponi, 277–89. University of Massachusetts Press.

Baker, Houston A., Jr. 1984. Blues, Ideology, and Afro-American Literature: A Vernacular Theory. University of Chicago Press.

Barrett, Frank J. 2012. Yes to the Mess: Surprising Leadership Lessons from Jazz. Harvard Business Review Press.

Bartlett, Andrew W. 1995. “Cecil Taylor, Identity Energy, and the Avant-Garde African American Body.” Perspectives of New Music 33 (1–2): 274–93.

Bastien David T., and Todd J. Hostager. 1988. “Jazz as a Process of Organizational Innovation.” Communication Research 15 (5): 582–602.

—————. 1991. “Jazz as Social Structure, Process, and Outcome.” In Jazz in Mind: Essays on the History and Meanings of Jazz, edited by Reginald T. Buckner and Steven Weiland, 148–65. Wayne State University Press.

Bauman, Zygmunt. 2000. Liquid Modernity. Polity.

—————. 2007. Liquid Times. Polity.

—————. 2011. Culture in a Liquid Modern World. Polity.

Beal, Amy C. 2011. Carla Bley. University of Illinois Press.

Benadon, Fernando. 2006. “Slicing the Beat: Jazz Eighth-Notes as Expressive Microrhythm.” Ethnomusicology 50 (1): 73–98.

Berliner, Paul. 1994. Thinking in Jazz: The Infinite Art of Improvisation. University of Chicago Press.

Blesh, Rudi. 1946. Shining Trumpets: A History of Jazz. Knopf.

Borgo, David. 2006. Sync or Swarm: Improvising Music in a Complex Age. Continuum.

Bourdieu, Pierre. 1977. Outline of a Theory of Practice, translated by Richard Nice. Cambridge University Press.

Brand, Gail, John Sloboda, Ben Saul, and Martin Hathaway. 2012. “The Reciprocal Relationship Between Jazz Musicians and Audiences in Live Performances: A Pilot Qualitative Study.” Psychology of Music 40 (5): 634–51.

Brinner, Benjamin. 1995. Knowing Music, Making Music: Javanese Gamelan and the Theory of Musical Competence and Interaction. University of Chicago Press.

Brothers, Thomas. 1994. “Solo and Cycle in African-American Jazz.” The Musical Quarterly 78 (3): 479–509.

—————. 2006. Louis Armstrong’s New Orleans. Norton.

—————. 2014. Louis Armstrong: Master of Modernism. Norton.

Burford, Mark. 2014. “Mahalia Jackson Meets the Wise Men: Defining Jazz at the Music Inn.” The Musical Quarterly 97 (3): 429–86.

Butterfield, Matthew. 2010. “Participatory Discrepancies and the Perception of Beats in Jazz.” Music Perception 27 (3): 157–75.

Caines, Rebecca, and Ajay Heble. 2015. “Prologue: Spontaneous Acts.” In The Improvisation Studies Reader: Spontaneous Acts, edited by Rebecca Caines and Ajay Heble, 1–5. Routledge.

Canonne, Clément. 2013. “Focal Points in Collective Improvisation.” Perspectives of New Music 51 (1): 40–55.

Canonne, Clément, and Nicolas B. Garnier. 2011. “A Model for Collective Free Improvisation.” In Mathematics and Computation in Music: Third International Conference, MCM 2011, Paris, France, June 2011: Proceedings, edited by Carlos Agon, Moreno Andreatta, Gérard Assayag, Emmanuel Amiot, Jean Bresson, and John Mandereau, 29–41. Springer.

—————. 2012. “Cognition and Segmentation in Collective Free Improvisation: An Exploratory Study.” In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on Music Perception and Cognition and the 8th Triennial Conference of the European Society for the Cognitive Study of Music, edited by E. Cambouropoulos, C. Tsougras, P. Mavromatis, and K. Pastiadis, 197–204. Thessaloniki: School of Music Studies, Aristotle University.

Caporaletti, Vincenzo. 2014. Swing e Groove: Sui Fondamenti Estetici delle Musiche Audiotattili. Libreria Musicale Italiana.

Carr, Ian. 1998. Miles Davis: The Definitive Biography. Thunder’s Mouth Press.

Carson, Charles D. 2008. “ ‘Bridging the Gap’: Creed Taylor, Grover Washington Jr., and the Crossover Roots of Smooth Jazz.” Black Music Research Journal 28 (1): 1–15.

Clark, Gregory. 2015. Civic Jazz: American Music and Kenneth Burke on the Art of Getting Along. University of Chicago Press.

Clark, Suzannah. 2007. “The Politics of the Urlinie in Schenker’s Der Tonwille and Der freie Satz.” Journal of the Royal Musical Association 132: 141–64.

Clayton, Martin. 2013. “Entrainment, Ethnography, and Musical Interaction.” In Experience and Meaning in Music Performance, edited Martin Clayton, Byron Dueck, and Laura Leante, 17–39. Oxford University Press.

Cohen, Aaron. 2008. “Jazz Impact Brings Improvisation to Corporate Communications.” Down Beat, July: 16.

Cook, Nicholas. 2004. “Making Music Together, or Improvisation and its Others.” The Source: Challenging Jazz Criticism 1: 5–25.

—————. 2005. “Prompting Performance: Text, Script, and Analysis in Bryn Harrison’s être-temps.” Music Theory Online 11 (1).

—————. 2007. The Schenker Project: Culture, Race, and Music Theory in Fin-de-Siècle Vienna. Oxford University Press.

—————. 2013. Beyond the Score: Music as Performance. Oxford University Press.

Coolman, Todd F. 1997. “The Miles Davis Quintet of the Mid-1960s: Synthesis of Improvisational and Compositional Elements.” Ph.D. Diss., New York University.

Corbett, John. 2016. A Listener’s Guide to Free Improvisation. University of Chicago Press.

Curth, Oliver. 1990. “Untersuchungen zu Big Band Arrangements von Thad Jones für das Thad Jones–Mel Lewis Jazz Orchestra.” Jazzforschung 22: 53–117.

Davis, Bob. 2005. “A Vocalist’s Best Friend: Pianists and Singers Discuss the Art of the Accompanist.” Down Beat, September: 48–52.

De Pree, Max. 1992. Leadership Jazz. Dell.

Dean, Roger T., and Freya Bailes. 2010. “The Control of Acoustic Intensity During Jazz and Free Improvisation Performance: Possible Transcultural Implications for Social Discourse and Community.” Critical Studies in Improvisation 6 (2): 1–22.

DeVeaux, Scott. 1997. The Birth of Bebop: A Social and Musical History. University of California Press.

—————. 1998. “Constructing the Jazz Tradition.” In The Jazz Cadence of American Culture, edited by Robert G. O’Meally, 488–99. Columbia University Press.

Doffman, Mark. 2005. “Groove! Its Production, Perception, and Meaning in Jazz.” M.A. Thesis, University of Sheffield.

—————. 2011. “Jammin’ an Ending: Creativity, Knowledge, and Conduct among Jazz Musicians.” Twentieth-Century Music 8 (2): 203–25.

—————. 2013. “Groove: Temporality, Awareness, and the Feeling of Entrainment in Jazz Performance.” In Experience and Meaning in Music Performance, edited by Martin Clayton, Byron Dueck, and Laura Leante, 62–85. Oxford University Press.

Dunkel, Mario. 2012. “Marshall Winslow Stearns and the Politics of Jazz Historiography.” American Music 30 (4): 468–504.

Dybo, Tor. 1999. “Analyzing Interaction During Jazz Improvisation.” Jazzforschung 31: 51–64.

Ellison, Ralph. 2001. “The Charlie Christian Story.” In Living with Music: Ralph Ellison’s Jazz Writings, edited by Robert G. O’Meally, 34–42. Modern Library.

Elsdon, Peter. 2013. Keith Jarrett’s The Köln Concert. Oxford University Press.

Enright, Ed. 2009. “Louie Bellson, Roy Haynes, Elvin Jones, and Max Roach: Once in a Lifetime.” In Down Beat: The Great Jazz Interviews, edited by Frank Alkyer and Ed Enright, 295–98. Hal Leonard.

Enstice, Wayne, and Paul Rubin. 1992. “Chico Hamilton.” In Jazz Spoken Here: Conversations with Twenty-Two Musicians, 185–96. Louisiana State University Press.

Evans, Sara M., and Harry C. Boyte. 1992. Free Spaces: The Sources of Democratic Change in America. University of Chicago Press.

Finkelstein, Sidney. 1948. Jazz: A People’s Music. The Citadel Press.

Fischlin, Daniel, and Ajay Heble. 2004. “The Other Side of Nowhere: Jazz, Improvisation, and Communities in Dialogue.” In “The Other Side of Nowhere”: Jazz, Improvisation, and Communities in Dialogue, edited by Daniel Fischlin and Ajay Heble, 1–42. Wesleyan University Press.

Fischlin, Daniel, Ajay Heble, and George Lipsitz. 2013. The Fierce Urgency of Now: Improvisation, Rights, and the Ethics of Cocreation. Duke University Press.

Floyd, Samuel A., Jr. 1995. The Power of Black Music: Interpreting Its History from Africa to the United States. Oxford University Press.

Gates, Henry Louis, Jr. 1988. The Signifying Monkey: A Theory of African-American Literary Criticism. Oxford University Press.

Gendron, Bernard. 2002. “Moldy Figs and Modernists.” In Between Montmartre and the Mudd Club: Popular Music and the Avant-Garde, 121–41. University of Chicago Press.

Gennari, John. 2006. Blowin’ Hot and Cool: Jazz and Its Critics. University of Chicago Press.

Giddins, Gary, and Scott DeVeaux. 2009. Jazz. W. W. Norton.

Gillespie, Dizzy, with Al Fraser. 1979. To Be, or Not

Givan, Benjamin. 2014. “Gunther Schuller and the Challenge of Sonny Rollins: Stylistic Context, Intentionality, and Jazz Analysis.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 67 (1): 167–237.

Gleason, Ralph J. 2016. Conversations in Jazz: The Ralph J. Gleason Interviews. Yale University Press.

Goebel, Werner, and Caroline Palmer. 2009. “Synchronization of Timing and Motion Among Performing Musicians.” Music Perception 26 (5): 427–38.

Goffin, Robert. 1944. Jazz: From the Congo to the Metropolitan, translated by Walter Schaap and Leonard G. Feather. Doubleday, Doran, & Co.

Goldberg, Joe. 1965. “Gerry Mulligan.” In Jazz Masters of the Fifties, 9–23. Macmillan.

Golson, Benny, and Jim Merod. 2016. Whisper Not: The Autobiography of Benny Golson. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Gratier, Maya. 2008. “Grounding in Musical Interaction: Evidence from Jazz Performances.” Musicae Scientiae 12 (1): 71–110.

Greenland, Thomas H. 2016. Jazzing: New York City’s Unseen Scene. University of Illinois Press.

Gross, Terry. 1997. “Remembering Saxophonist Steve Lacy.” Fresh Air. Radio Broadcast. WHYY, Philadelphia, November 20.

Gushee, Lawrence. 1998. “Improvisation of Louis Armstrong.” In In the Course of Performance: Studies in the World of Musical Improvisation, edited by Bruno Nettl and Melinda Russell, 291–334. University of Chicago Press.

“H. Con. Res. 57” [1987]. 1999. Reprinted in Keeping Time: Readings in Jazz History, edited by Robert Walser, 332–33. Oxford University Press.

Haney, Joel. 2013. “Musicking in the ‘Between’: Player-Directed Form and Contemporaneity in Hindemith’s Duo Sonatas.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Musicological Society, Pittsburgh, Penn.

Harker, Brian. 2011. Louis Armstrong’s Hot Five and Hot Seven Recordings. Oxford University Press.

Hentoff, Nat. 1959. “Miles Davis: Last Trump.” Esquire 51 (March): 88–90.

Hirsch, Ira J. 1959. “Auditory Perception of Temporal Order.” Journal of the Acoustic Society of America 31: 759–67.

Hobson, Vic. 2014. Creating Jazz Counterpoint: New Orleans, Barbershop Harmony, and the Blues. University Press of Mississippi.

Hodeir, André. 1956. Jazz: Its Evolution and Essence, translated by David Noakes. Grove Press.

Hodson, Robert. 2007. Interaction, Improvisation, and Interplay in Jazz. Routledge.

Horn, David. 2000. “The Sound World of Art Tatum.” Black Music Research Journal 20 (2): 237–57.

Howe, Jeff. 2008. Crowdsourcing: Why the Power of the Crowd is Driving the Future of Business. Three Rivers Press.

Howland, John. 2009. Ellington Uptown: Duke Ellington, James P. Johnson, and the Birth of Concert Jazz. University of Michigan Press.

Hughes, Langston. 1958. “Jazz as Communication.” In The Langston Hughes Reader, 492–94. George Braziller.

Iverson, Ethan. 2014. “Interview with Bob Cranshaw.”

Iyer, Vijay. 2002. “Embodied Mind, Situated Cognition, and Expressive Microtiming in African-American Music.” Music Perception 19 (3): 387–414.

—————. 2004. “Exploding the Narrative in Jazz Improvisation.” In Uptown Conversation: The New Jazz Studies, edited by Robert G. O’Meally, Brent Hayes Edwards, and Farah Jasmine Griffin, 393–403. Columbia University Press.

Jackson, Travis A. 2012. Blowin’ the Blues Away: Performance and Meaning on the New York Jazz Scene. University of California Press.

Jankowsky, Richard C. 2016. “The Medium is the Message? Jazz Diplomacy and the Democratic Imagination.” In Jazz Worlds/World Jazz, edited by Philip V. Bohlman and Goffredo Plastino, 258–88. University of Chicago Press.

Keil, Charles. 1966. “Motion and Feeling through Music.” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 24: 337–49.

—————. 1987. “Participatory Discrepancies and the Power of Music.” Cultural Anthropology 2: 275–83.

Keil, Charles, et al. 1995. “Special Issue: Participatory Discrepancies.” Ethnomusicology 39: 1–104.

Kelley, Robin D. G. 2001. “In a Mist: Thoughts on Ken Burns’s Jazz.” Institute for Studies in American Music Newsletter 30 (2): 8–10, 15.

Kernfeld, Barry. 2002. “Sonny Rollins.” In The New Grove Dictionary of Jazz, edited by Barry Kernfeld, 3: 444–47. Macmillan.

Kingsbury, Henry. 1988. Music, Talent, and Performance: A Conservatory Cultural System. Temple University Press.

Krugman, Paul. 1995. Development, Geography, and Economic Theory. MIT Press.

Lajoie, Steve. 2003. Gil Evans and Miles Davis: Historic Collaborations: An Analysis of Selected Gil Evans Works 1957–1962. Advance Music.

Laver, Mark. 2016. “The Share: Improvisation and Community in the Neoliberal University.” In Improvisation and Music Education: Beyond the Classroom, edited by Ajay Heble and Mark Laver, 232–57. Routledge.

Le Guin, Elisabeth. 2002. “ ‘One Says That One Weeps, But One Does Not Weep’: Sensibile, Grotesque, and Mechanical Embodiments in Boccherini’s Chamber Music.” Journal of the American Musicological Society 55 (2): 207–54.

Lee, Newton. 2014. Facebook Nation: Total Information Awareness. Springer.

Lewis, George E. 2009. “Interactivity and Improvisation.” In The Oxford Handbook of Computer Music, edited by Roger T. Dean, 457–66. Oxford University Press.

Littlefield, Richard, and David Neumeyer. 1992. “Rewriting Schenker: Narrative—History—Ideology.” Music Theory Spectrum 14 (1): 38–65.

Love, Stefan Caris. 2016. “The Jazz Solo as Virtuous Act.” Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism 74 (1): 61–74.

Lyons, Len. 1983. The Great Jazz Pianists. William Morrow.

Magee, Jeffrey. 2005. The Uncrowned King of Swing: Fletcher Henderson and Big Band Jazz. Oxford University Press.

Magrini, Tullia. 1998. “Improvisation and Group Interaction in Italian Lyrical Singing.” In In the Course of Performance: Studies in the World of Musical Improvisation, edited by Bruno Nettl and Melinda Russell, 169–98. University of Chicago Press.

Margulis, Elizabeth Hellmuth. 2014. On Repeat: How Music Plays the Mind. Oxford University Press.

Martin, Henry. 2005. “Balancing Composition and Improvisation in James P. Johnson’s ‘Carolina Shout.’ ” Journal of Music Theory 49 (2): 277–99.

Massimo, Rick. 2008. “Great as He Is, Sonny Rollins Still Searching.” Providence Journal, August 8.

Maultsby, Portia. 1990. “Africanisms in African-American Music.” In Africanisms in American Culture, edited by Joseph E. Holloway, 185–210. Indiana University Press.

McClary, Susan. 1987. “The Blasphemy of Talking Politics During Bach Year.” In Music and Society: The Politics of Composition, Performance, and Reception, edited by Richard Leppert and Susan McClary, 13–62. Cambridge University Press.

—————. 1991. “Sexual Politics in Classical Music.” In Feminine Endings: Music, Gender, and Sexuality, 53–79. University of Minnesota Press.

McMillan, Jeffery S. 2008. Delightfulee: The Life and Music of Lee Morgan. University of Michigan Press.

Meyer, Leonard B. 1973. Explaining Music: Essays and Explorations. University of California Press.

Michaelsen, Garrett. 2013a. “Analyzing Musical Interaction in Jazz Improvisations of the 1960s.” Ph.D. Diss., Indiana University.

—————. 2013b. “Groove Topics in Improvised Jazz.” In Analyzing the Music of Living Composers (and Others), edited by Jack Boss, Brad Osborn, Tim S. Pack, and Stephen Rodgers, 176–91. Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Monson, Ingrid. 1994. “Doubleness and Jazz Improvisation: Irony, Parody, and Ethnomusicology.” Critical Inquiry 20 (2): 283–313.

—————. 1996. Saying Something: Jazz Improvisation and Interaction. University of Chicago Press.

—————. 1999. “Riffs, Repetition, and Theories of Globalization.” Ethnomusicology 43 (1): 31–65.

—————. 2001. “Jazz.” In The Garland Encyclopedia of World Music, Volume 3: The United States and Canada, edited by Ellen Koskoff, 650–66. Garland Publishing.

—————. 2002. “Jazz Improvisation.” In The Cambridge Companion to Jazz, edited by Mervyn Cooke and David Horn, 114–132. Cambridge University Press.

—————. 2007. Freedom Sounds: Civil Rights Call Out to Jazz and Africa. Oxford University Press.

—————. 2009. “Jazz as Political and Musical Practice.” In Musical Improvisation: Art, Education, and Society, edited by Gabriel Solis and Bruno Nettl, 21–37. University of Illinois Press.

Myers, Marc. 2012. “Interview: Bob Whitlock (Part 3).” August 8.

Napier, Winston, ed. 2000. African American Literary Theory: A Reader. New York University Press.

Nettl, Bruno, and Ronald Riddle. 1973. “Taqsim Nahawand: A Study of Sixteen Performances by Jihad Racy.” Yearbook of the International Folk Music Council 5: 11–50.

Nettl, Bruno. 1974. “Thoughts on Improvisation: A Comparative Approach.” The Musical Quarterly 60 (1): 1–19.

—————. 1995. Heartland Excursions: Ethnomusicological Reflections on Schools of Music. University of Illinois Press.

Palmer, Caroline. 1997. “Musical Performance.” Annual Review of Psychology 48: 115–38.

Panassié, Hugues. 1936. Hot Jazz: The Guide to Swing Music, translated by Lyle and Eleanor Dowling. M. Witmark & Sons.

—————. 1944. Histoire des Disques Swing: Enregistrés à New-York par Tommy Ladnier, Mezz Mesirow, Frank Newton, etc. Grasset.

Panken, Ted. 2013. “R.I.P. Chico Hamilton.” November 26.

Perchard, Tom. 2006. Lee Morgan: His Life, Music, and Culture. Equinox.

—————. 2011a. “Thelonious Monk Meets the French Critics: Art and Entertainment, Improvisation, and its Simulacrum.” Jazz Perspectives 5 (1): 61–94.

—————. 2011b. “Tradition, Modernity, and the Supernatural Swing: Re-Reading ‘Primitivism’ in Hugues Panassié’s Writing on Jazz.” Popular Music 30 (1): 25–45.

Peterson, Oscar. 2002. A Jazz Odyssey: The Life of Oscar Peterson. Continuum.

Porter, Lewis, and Michael Ullman. 1993. Jazz: From Its Origins to the Present. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Prouty, Ken. 2013. “Finding Jazz in the Jazz-As-Business Metaphor.” Jazz Perspectives 7 (1): 31–55.

Raeburn, Bruce Boyd. 2009. New Orleans Style and the Writing of American Jazz History. University of Michigan Press.

Ramsey, Guthrie P., Jr. 2001. “Who Hears Here? Black Music, Critical Bias, and the Musicological Skin Trade.” The Musical Quarterly 85 (1): 1–52.

—————. 2013. The Amazing Bud Powell: Black Genius, Jazz History, and the Challenge of Bebop. University of California Press.

Rasch, Rudolf A. 1988. “Timing and Synchronization in Ensemble Performance.” In Generative Processes in Music: The Psychology of Performance, Improvisation, and Composition, edited by John A. Sloboda, 70–90. Clarendon Press.

Reinholdsson, Peter. 1998. “Making Music Together: An Interactionist Perspective on Small Group Performance.” Ph.D. Diss., Uppsala University.

Rinzler, Paul. 1988. “Preliminary Thoughts on Analyzing Musical Interaction Among Jazz Performers.” Annual Review of Jazz Studies 4: 153–60.

—————. 2008. The Contradictions of Jazz. Scarecrow Press.

Ross, Alex. 2009. “The Music Mountain.” The New Yorker, June 29: 56–65.

Sarath, Ed. 2005. “Jazz Lessons for the Boardroom.” Newsday, May 14.

Sawyer, R. Keith. 1997. “Improvisational Theater: An Ethnotheory of Conversational Practice.” In Creativity in Performance, edited by R. Keith Sawyer, 171–93. Ablex.

—————. 2003. Group Creativity: Music, Theater, Collaboration. Lawrence Earlbaum Associates.

—————. 2005. “Music and Conversation.” In Musical Communication, edited by Dorothy Miell, Raymond MacDonald, and David J. Hargreaves, 45–60. Oxford University Press, 2005.

Schenker, Heinrich. 1997. “Rameau or Beethoven? Creeping Paralysis or Spiritual Potency in Music?,” translated by Ian Bent. In The Masterwork in Music: A Yearbook, Volume III (1930), edited by William Drabkin, 1–9. Cambridge University Press.

Schiavio, Andreas, and Simon Høffding. 2015. “Playing Together without Communicating? A Pre-Reflective and Enactive Account of Joint Musical Performance.” Musicae Scientiae 19 (4): 366–88.

Schuller, Gunther. 1958. “Sonny Rollins and the Challenge of Thematic Improvisation.” Jazz Review 1 (1): 6–11, 21.

—————. 1968. Early Jazz: Its Roots and Musical Development. Oxford University Press.

—————. 1989. The Swing Era: The Development of Jazz 1930–1945. Oxford University Press.

Schütz, Alfred. 1951. “Making Music Together: A Study in Social Relationship.” Social Research 18 (1): 76–97.

Seddon, Frederick, and Michele Biasutti. 2009. “A Comparison of Modes of Communication between Members of a String Quartet and a Jazz Quartet.” Psychology of Music 37: 395–415.

Sennett, Richard. 2012. Together: The Rituals, Pleasures, and Politics of Cooperation. Yale University Press.

Sidran, Ben. 1995. Talking Jazz: An Oral History. Expanded Edition. Da Capo Press.

Siegel, Robert. 1997. “Interview with Herbie Hancock/Tony Williams Obituary.” All Things Considered. Radio Broadcast. National Public Radio, February 25.

Silver, Horace. 2006. Let’s Get to the Nitty Gritty: The Autobiography of Horace Silver, edited by Phil Pastras. University of California Press.

Small, Christopher. 1998. Musicking: The Meanings of Performing and Listening. Wesleyan University Press.

Smith, Hazel, and Roger T. Dean. 1997. Improvisation, Hypermedia, and the Arts Since 1945. Harwood.

Solal, Martial. 2011. “Entrevue avec Martial Solal.” Gruppen 2 (Winter): 71–83.

Solis, Gabriel. 2006. “Avant-Gardism, the ‘Long 1960s,’ and Jazz Historiography.” Journal of the Royal Musical Association 131 (2): 331–49.

—————. 2008. Monk’s Music: Thelonious Monk and Jazz History in the Making. University of California Press.

Spring, Evan. 1999. “Review of Ingrid Monson, Saying Something.” Annual Review of Jazz Studies 10: 291–308.

Stanbridge, Alan. 2008. “From the Margins to the Mainstream: Jazz, Social Relations, and Discourses of Value.” Critical Studies in Improvisation 4 (1).

Stearns, Marshall W. 1956. The Story of Jazz. Oxford University Press.

Steinbeck, Paul. 2008. “ ‘Area by Area the Machine Unfolds’: The Improvisational Performance Practice of the Art Ensemble of Chicago.” Journal of the Society for American Music 2 (3): 397–427.

—————. 2016. “Talking Back: Analyzing Performer–Audience Interaction in Roscoe Mitchell’s ‘Nonaah.’ ” Music Theory Online 22.3.

Stern, Chip. 1996. Liner Notes (“Pictures of Infinity”) accompanying Sonny Rollins, Silver City: A Celebration of 25 Years on Milestone. Milestone. 2MCD-2501-2.

Stewart, Alex. 2007. Making the Scene: Contemporary New York City Big Band Jazz. University of California Press.

Stewart, Milton L. 1986. “Player Interaction in the 1955–1957 Miles Davis Quintet.” Jazz Research Papers 6: 187–210.

Surowiecki, James. 2004. The Wisdom of Crowds: Why the Many Are Smarter Than the Few and How Collective Wisdom Shapes Business, Economies, Societies, and Nations. Doubleday.

Szwed, John F. 2000. Jazz 101: A Complete Guide to Learning and Loving Jazz. Hyperion.

Taylor, Billy. 1982. Jazz Piano: History and Development. William C. Brown.

Tomlinson, Gary. 1992. “Cultural Dialogics and Jazz: A White Historian Signifies.” In Disciplining Music: Musicology and Its Canons, edited by Katherine Bergeron and Philip V. Bohlman, 64–94. University of Chicago Press.

Ulanov, Barry. 1952. A History of Jazz in America. Viking Press.

Vaidhyanathan, Siva. 2011. The Googlization of Everything (And Why We Should Worry). University of California Press.

Walser, Robert. 1993. “Out of Notes: Signification, Interpretation, and the Problem of Miles Davis.” The Musical Quarterly 77 (2): 343–65.

—————. 1997. “Deep Jazz: Notes on Interiority, Race, and Criticism.” In Inventing the Psychological: Toward a Cultural History of Emotional Life in America, edited by Joel Pfister and Nancy Schnog, 271–98. Yale University Press.

Washburne, Christopher. 2004. “Does Kenny G Play Bad Jazz? A Case Study.” In Bad Music: The Music We Love to Hate, edited by Christopher Washburne and Maiken Derno, 123–47. Routledge.

Waters, Keith. 2011. The Studio Recordings of the Miles Davis Quintet, 1965–68. Oxford University Press.

Weick, Karl E. 1998. “Improvisation as a Mindset for Organizational Analysis.” Organization Science 9 (5): 543–55.

Wilf, Eitan Y. 2014. School for Cool: The Academic Jazz Program and the Paradox of Institutionalized Creativity. University of Chicago Press.

Zbikowski, Lawrence M. 2004. “Modelling the Groove: Conceptual Structure in Popular Music.” Journal of the Royal Musical Association 129 (2): 272–97.

Blakey, Art, and the Jazz Messengers. 1959. Moanin’. Blue Note 4003. LP.

Davis, Miles. 1957. Bags’ Groove. Prestige 7109. LP.

—————. 1958. Milestones. Columbia CL 1193. LP.

—————. 1995. The Complete Live at the Plugged Nickel. Columbia Legacy CK 66955. Compact disc.

Earland, Charles. 1971. Living Black! Prestige 10009. LP.

Eldridge, Roy, Clark Terry, and Dizzy Gillespie. 1975. The Trumpet Kings at Montreux ’75. Pablo 2310-754. Compact disc.

Ellington, Duke. 1959. Jazz Party. Columbia CL 1323. LP.

Evans, Bill. 1993. Marian McPartland’s Piano Jazz with Guest Bill Evans. The Jazz Alliance 12004. Compact disc.

Mulligan, Gerry. 1952. “Bernie’s Tune.” Pacific Jazz 601. 78rpm single.

—————. 1996. The Complete Pacific Jazz Recordings. Pacific Jazz 7243 8 38263 2. Compact disc.

Roach, Max. 1959. Deeds Not Words. Riverside 1122. LP.

Rollins, Sonny. 1957a. Saxophone Colossus. Prestige 7079. LP.

—————. 1957b. Tour de Force. Prestige 7207. LP.

Smith, Jimmy, and Wes Montgomery. 1966. The Dynamic Duo: Jimmy and Wes. Verve 8678. LP.

Taylor, Billy. 1999. Ten Fingers—One Voice. Arkadia Jazz 71602. Compact disc.

Burns, Ken. 2001. Jazz. PBS DVD.

Footnotes

* For their advice and assistance, I thank Matt Butterfield, Joel Haney, Gayle Murchison, Lewis Porter, and Gabriel Solis.

Return to text

1. Berliner 1994; Monson 1996. Two brief, though significant, studies of interaction in jazz that predate these contributions are Stewart 1986 and Rinzler 1988. See also Rinzler 2008, 101–9.

Return to text

2. Reinholdsson 1998; Dybo 1999; Al-Zand 2005; Benadon 2006; Borgo 2006, 59–82; Hodson 2007; Steinbeck 2008; Butterfield 2010; Jackson 2012, 155–204; Michaelsen 2013a.

Return to text

3. Michaelsen opts for a definition that is more generalized, objective, and disembodied, but that otherwise accords with the present formulation; in his view, “interactions are moments of intervention in which the collision of two separate streams results in an alteration of either or both of their paths” (2013a, 49). Needless to say, this article deals only with interaction between collaborating musicians, and not interaction involving extra-ensemble elements, such as the relationship between performers and a live audience (discussed in Ashe 1999; Jackson 2012, 151–54 and 187–215; Brand et al. 2012; Steinbeck 2016; and Greenland 2016, 139–68).

Return to text

4. The conversational dimension of Baroque counterpoint is noted by Monson (1996, 80–81). Pre-composed musical interaction is also discussed in Cook 2013, 260–63; and in Haney 2013. Naturally, even spontaneous improvisation is not based on purely ex nihilo creativity—it typically involves predetermined elements or strategies (see Smith and Dean 1997, 29; quoted in Dean 2010, 18).

Return to text

5. Another pianist, Bill Evans, expressly states that he prefers playing unaccompanied to working with a bass-and-drums rhythm section (“Conversation/Demonstration: The Touch of Your Lips—Evans Solo,” Marian McPartland’s Piano Jazz with Guest Bill Evans [The Jazz Alliance 12004], recorded Nov. 6, 1978), discussed in Michaelsen 2013a, 10. Apparently Evans was not initially enthusiastic about the interactive, non-walking accompanimental style of Scott La Faro, the bassist in his famous trio of the early 1960s (Golson and Merod 2016, 111).

Return to text

6. Examples include Taylor’s solo piano recordings of “In a Sentimental Mood” and “Laura” (slow rubato ballads), “Easy Like” (stride), “Night and Day” (walking tenths), and “Joy Spring” (bebop comping), all from his album Ten Fingers—One Voice (Arkadia Jazz 71602), recorded August 6–8, 1996. Taylor’s ethnographic authority is discussed in Ramsey 2001, 28–30. The use of a dialogic approach to solo playing is directly indicated by the title of drummer Max Roach’s unaccompanied recording “Conversation,” Deeds Not Words (Riverside 1122), recorded September 4, 1958, discussed in Porter and Ullman 1993, 265.

Return to text

7. Miles Davis, “Doxy,” Bags’ Groove (Prestige 7109), recorded June 29, 1954.

Return to text

8. Scholarship on the concept of “groove” in jazz includes Monson 1996, 26–72; Zbikowski 2004; Doffman 2005; Michaelsen 2013b; and Caporaletti 2014.

Return to text

9. One of the few possible, though equivocal, instances of motivic interaction occurs in measure 12, where Clarke fleetingly reinforces some of the eighth-note triplets that Silver initiated a bar earlier.

Return to text

10. Quoted in Stern 1996. Along the same lines, Rollins explains that his longtime bassist “Bob Cranshaw was a person I always hired because he maintained the fixed portion of it, and that would allow me to extemporize freely” (Massimo 2008). Cranshaw concurs, explaining that “because I’m really trying to play the changes in the bottom, I usually stay where I am. I can hear [Rollins] if he’s in another place” (Iverson 2014). For a historical perspective on the “fixed group—variable group” Afrodiasporic musical principle, which is implicit in these musicians’ remarks, see Brothers 1994; Brothers 2006, 286–88; and Brothers 2014, 6–7. Barry Kernfeld proposes that “if ever there was an argument for conceiving of jazz group playing not as a process of democratic, interdependent, musical conversation, but as being dominated by a great individual artist, that artist is Rollins” (2002, 446). See also Spring 1999, 296.

Return to text

11. For more examples of jazz improvisers expressing similar views, see Berliner 1994, 404–9.

Return to text

12. While playing alongside Haynes in Monk’s quartet, tenor saxophonist Johnny Griffin also found the drummer’s accompaniment to be overly active and complex (Sidran 1995, 207).

Return to text

13. This phenomenon is discussed in Berliner 1994, 348–52. Berliner’s work is my point of departure for the conceptual distinctions proposed here.

Return to text

14. Charles Keil’s well-known theory of participatory discrepancies, for example, is concerned with this sort of subtle temporal interplay between ensemble musicians (Keil 1966, Keil 1987, Keil et al. 1995). For a critique, see Butterfield 2010. For empirically grounded case studies, see Doffman 2011, 221–23; and Doffman 2013.

Return to text

15. Cook (2013, 237) cites Frederick Seddon and Michele Biasutti’s research on string quartet performance practice (Seddon and Biasutti 2009). See also Le Guin 2002, 220; discussed in Cook 2013, 257–58.

Return to text

16. Cook calls attention to John Potter’s description of a similar process of microinteraction occurring between classical vocalists as they mutually adjust their intonation when singing a Renaissance mass (Cook 2004, 17). See also Cook 2005; and Cook 2013, 225–26. Pianist Emanuel Ax characterizes classical chamber-music performance practice as a situation in which “no one leads and no one follows” (quoted in Ross 2009, 60). For a sociological perspective on collaborative interaction among classical chamber musicians, particularly in rehearsal, see Sennett 2012, 14–22.

Return to text

17. Humans cannot even detect which of two sounds occurs first unless they occur at least fifteen milliseconds apart. See Hirsch 1959. For an overview of empirical research on various aspects of timekeeping in musical performance, see Palmer 1997. For a phenomenological analysis of “the pluridimensionality of time simultaneously lived through by man and fellow man

Return to text

18. Miles Davis, “No Blues,” The Complete Live at the Plugged Nickel (Columbia Legacy CK 66955), recorded December 23, 1965 (third set).

Return to text

19. Michaelsen mentions this track in the course of an extensive discussion of tempo fluctuations in the Davis Quintet’s performance of “The Theme” from the Plugged Nickel recordings (2013a, 169–72).

Return to text

20. According to Doffman, “within jazz, the aesthetic seems to demand a very open approach to shared time; the discursive positions that the players adopt are about looseness, flexibility and fluidity” (2013, 81).

Return to text

21. Duke Ellington, “Ready Go!” (from Toot Suite), Jazz Party (Columbia CL 1323), recorded February 19, 1959.

Return to text

22. “Ready Go!” begins at track time 15:14 (rather than 0:00) because it is the final section of Ellington’s Toot Suite, whose six sections were all programmed together as a single digital track on the album’s compact disc edition.

Return to text

23. Various musicians’ comments on this sort of interaction are quoted in Berliner 1994, 353–68.

Return to text

24. Macrointeraction includes, but is not limited to, what Paul Rinzler describes as a rhythm section “responding to the ‘peaks’ of the soloist” (1988, 157), as well as two phenomena discussed by Michaelsen: “interaction with ensemble roles and functions” (2013a, 115) and “interaction with musical styles” (2013a, 148). See also Michaelsen 2013b.

Return to text

25. Roy Eldridge, Clark Terry, and Dizzy Gillespie, “Montreux Blues,” The Trumpet Kings at Montreux ’75 (Pablo 2310-754), recorded July 16, 1975.

Return to text

26. Likewise, the ensemble’s drummer, Bellson, reflects that “I was always taught to be an accompanist until it was time to solo. I learned that from Dizzy, too. To be able to hear a soloist, what they’re playing, so that you can give them proper backing. Sometimes, in the rhythm section, if the piano and the bass and the drums are all comping at the same time, it’s too busy and the soloist has to turn around and say, ‘Wait a minute, what’s going on? Where are the fundamentals?’ ” (Enright 2009, 298).

Return to text

27. Partly quoted in Ramsey 2013, 137. See also Gleason 2016, 77.

Return to text

28. My concept of “motivic interaction” is somewhat broader than what Rinzler calls “common motive” interaction, which is restricted to “the exact repetition of a phrase either rhythmically or melodically” (1988, 157).

Return to text

29. Miles Davis, “Straight No Chaser,” Milestones (Columbia CL 1193), recorded February 4, 1958.

Return to text

30. Because the piano is quite far back in the recording mix, my transcription of Garland’s comping is only an approximation. I am relatively confident, however, about the notation of the uppermost piano notes in measure 4.

Return to text

31. Sonny Rollins, “Blue 7,” Saxophone Colossus (Prestige 7079), recorded June 22, 1956. For more on this recording, and on Schuller’s analysis, see Givan 2014.

Return to text

32. See, for example, Maultsby 1990, 193; and Floyd 1995 95–96 and passim.

Return to text

33. Sonny Rollins, “Sonny Boy,” Tour de Force (Prestige 7207), recorded December 7, 1956.

Return to text

34. Musical interaction involving elements that are in tension with one another is somewhat akin to the sort of “divergent” group creativity described by Sawyer 1997, 187 and discussed in a musical context by Steinbeck 2008, 402 and Michaelsen 2013a, 59–61.

Return to text

35. For more on Williams’s interactive performance strategies with the Davis Quintet, see Coolman 1997, 77–85; and Waters 2011, 73–74 and passim.

Return to text

36. For instance, in “Blue 7,” as Flanagan interacts motivically with Rollins, the players also engage in macrointeraction insofar as their individual contributions are stylistically compatible and are at similar intensity levels. And at the same time, they engage in microinteraction in order to stay temporally coordinated.

Return to text

37. For a thorough theoretical overview of various varieties of call-and-response interaction, see Reinholdsson 1998, 213–18.

Return to text

38. Jimmy Smith and Wes Montgomery, “Down by the Riverside,” The Dynamic Duo: Jimmy and Wes (Verve 8678), recorded September 23, 1966.

Return to text

39. Elizabeth Hellmuth Margulis notes that “the ability to repeat another person’s musical utterance lies at the heart of what we understand as musical communication” (2014, 136).

Return to text

40. At this point in the performance, Smith and Montgomery’s interplay is suggestive of two of the general classifications of interaction that Canonne and Garnier identify in their theory of collective free musical improvisation: Montgomery first adopts a “playing along” strategy by “play[ing] what he is implicitly expected to play,” whereupon Smith chooses a “densification strategy” by “deliberately creat[ing] complexity” (2012, 202).

Return to text

41. One of the anonymous reviewers of this article notes that this riff is quite similar to Charles Earland’s blues head, recorded several years later, “Key Club Cookout,” Living Black! (Prestige 10009), recorded September 17, 1970.

Return to text

42. For an empirical perspective on symmetrical musical interactions, see Canonne and Garnier 2011, 39–40.

Return to text

43. Art Blakey and the Jazz Messengers, “Moanin’,” Moanin’ (Blue Note 4003), recorded October 30, 1958.

Return to text

44. On the reception of “Moanin’,” see McMillan 2008, 87; see also Perchard 2006, 87.

Return to text

45. Gerry Mulligan, “Bernie’s Tune” (Pacific Jazz 601), recorded August 16, 1952.

Return to text

46. See also Chico Hamilton’s comments on playing with pianoless groups (Enstice and Rubin 1992, 194).

Return to text