Glenn Gould, Spliced: Investigating the Filmmaking Analogy

Garreth P. Broesche

KEYWORDS: Glenn Gould, music and technology, recording, filmmaking, ontology, Walter Benjamin, aura, Sergei Eisenstein, Johannes Brahms

ABSTRACT: Glenn Gould often drew an analogy: live theater is to film as concert performance is to studio recording. In his writings, Gould cites one finished “performance” created by splicing together two contrasting interpretations of a piece; through editing, the finished version somehow becomes more than the sum of its parts. Here Gould’s use of editing appears to invoke montage technique in a manner similar to one of its uses in film: contrasting images (interpretations) are juxtaposed, bequeathing responsibility to the viewer (listener) to infer meaning not explicitly present in either. To paraphrase Walter Benjamin, the use of montage technique separates filmmaking from live theater, altering the ontological status of the former and elevating it to an independent art form. Do the ways in which Gould employs technology support the claim that there is a similar relationship between live and studio music?

For all the extant literature on Gould, there is little that discusses—in detail—his actual studio process. Scholars have tended to take Gould at his word. However, I believe that only by placing the focus squarely on the historical truth may we evaluate his recording/filmmaking analogy. This paper centers on a detailed audio analysis of one Gould performance: his 1981 recording of a Brahms Ballade. I will present original research into archival documents and clips of studio outtakes, and I will discuss my own re-creation of Gould’s splicing scheme.

My research allows me to make two claims regarding Gould’s studio process. First, Gould’s understanding of the function of studio recording is quite different from the commonplace notion that that recording studio is a means to create a simulacrum of the live event. And, second, his use of montage technique is quite a bit “weaker” than his own words on the recording/filmmaking analogy might lead one to believe.

Copyright © 2016 Society for Music Theory

Part 1. The filmmaking analogy

[1.1] In “The Prospects of Recording,” his 1966 essay for High Fidelity magazine, pianist Glenn Gould discusses his 1956 recording of the A-minor Fugue from Book I of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier (Gould 1992a). For the recording, he set down two complete takes—Takes 6 and 8—that were deemed technically acceptable. However, Gould later discovered that, as he wrote, “both had a defect [of] which [I] had been quite unaware in the studio: both were monotonous” (Gould 1966, 52). Gould concluded that

The somewhat overbearing posture of Take 6 was entirely suitable for the opening exposition as well as the concluding statement of the fugue, while the more effervescent character of Take 8 was a welcome relief in the

. . . center portion. (1966, 52)

Example 1. Mm. 13–15 of Bach’s A-minor Fugue, showing the location of the first tape splice in Glenn Gould 1956 recording of the work

(click to enlarge)

Two splices were made: Take 6 opened the recording, was swapped out for Take 8 at m. 14, and cut back in towards the end of the piece. It is difficult to hear the second splice and Gould’s only clue (given in “The Prospects of Recording”) is that it occurred “at the return of A minor” (53). He claims to have forgotten exactly where but invites the listener/reader to search for it. Taking up his challenge, Paul Sanden believes he has located the second splice just before the downbeat of m. 55 (2003, 78). Gould writes “what [was] achieved was a performance . . . far superior to anything we could . . . have done [live] in the studio” (1966, 53). The result is a montage of interpretations: a performance that never occurred was constructed after careful evaluation of the rough material. At the edge of a razor blade, two acceptable but monotonous performances are transformed into one superior recording. Example 1 presents mm. 13–15 of this fugue; the vertical line locates the first splice (the splice occurs thirty seconds into the recording).

Audio Example 1

[1.2] Listening to Gould’s recording of the A-minor Fugue in light of his explanation, the first edit becomes audible. It is not easy to hear the splice exactly—that remains silent—and only a very attentive listener would register the shift in interpretation without having been alerted to it.(1) The character of the playing, however, does change palpably at the moment indicated in Example 1, above. The upright, mechanical regularity of Gould’s playing is replaced by a more free and flowing style; it is almost as if a second character taps the first on the shoulder and abruptly takes over the telling of a narrative. This portion of music is presented as Audio Example 1, which provides roughly the first forty-five seconds of the recording.

[1.3] Gould quit the concert stage in 1964 in order to devote himself entirely to recording and other media. This decision, of course, was radical in its time. Gould argued that he was able to speak to his audience more intimately, that he had found “a much more direct means of communication” through recording (Monsaigneon 2002). Further, Gould dismisses the positive aspects listeners enjoy about the concert-going experience: “there is simply no scientific-acoustical-human way in which [live events], no matter how glamorous, no matter how dramatic, can equal what one [can achieve] in the privacy, in the hermetically-sealed privacy, of this studio” (Monsaigneon 2002).

[1.4] Gould’s rationale—that the recording studio allows for greater intimacy than the concert hall—was just as radical as his decision to retire from the stage. In order to defend himself from both real and imagined attacks, Gould—and his intellectual allies—frequently drew an analogy between filmmaking and studio recording.(2) Just as a filmmaker need not be confined by the conditions of live theater, Gould argued that a recording musician need not follow the conventions of the concert hall.

[1.5] As Jonathan Sterne writes, it is often thought that live music maintains a special element, a “fullness and self-presence in the

[1.6] Early twentieth-century filmmaker Sergei Eisenstein was aware of the problem of loss of aura as it relates to the relationship between live theater and film. He writes:

[In cinema] there is no physical reality, only the grey shadow of its reflection. Therefore in order to make good the absence of the principal factor—the live, immediate contact between the person in the auditorium and the person on stage—we have to find ways and means other than those used in theater. (Eisenstein 2010, 134)

How might a director compensate for the loss of presence? Eisenstein offers, then immediately rejects, an approach that might seem to be the most naturalistic manner in which to transpose the staged scene to the screen: that of a single camera in long take. As Eisenstein writes, such an approach “turns out to be a hopeless failure on the screen” (2010, 134). Eisenstein instead advocates for adding further layers of mediation in order to achieve the effect of the original, unmediated performance:

Let us take the scene of a murder. Shot head-on in “long shot,” it would produce about 25 percent of the effect that it produced on stage. Let us try and present it in another way. Let us break it down into close-up and medium shot, and into the whole ... series of shots of “hands gripping throat,” “eyes starting from their sockets,” and so on and so forth. “Cunningly” edited, skillfully set in the appropriate tempo, graphically put together, these shots as a whole can produce exactly the same 100 per cent effect as that produced on stage. (2010, 134)

In filmmaking, more mediation is the means to compensate for the loss of physical proximity, first-hand experience, and the uniqueness of the live event. Contrasting shots and multiple cameras are employed; events are captured in an order dictated by exigencies of production rather than the script. Only when the director puts the pieces together is the emotional impact of the scene recreated for the screen.

[1.7] Eisenstein argues that such a way of presenting a story calls upon the viewer to be more actively involved in the experience:

These separate fragments function not as depiction but as stimuli that provoke associations. [This approach]. . . forces our imagination to add to them and thereby activates to an unusual degree the spectator’s emotions and intellect. (2010, 134–35)

This approach—pioneered by Eisenstein—has come to be called intellectual montage (Bordwell and Thompson 2004, 503). This is a compensatory strategy for the Russian director: presence or no, he argues, such a presentation is every bit as involving as live theater. Benjamin seems to agree with Eisenstein on this point. He writes that what is delivered in film is “an equipment-free aspect of reality [that the viewer is] entitled to demand from a work of art” (Benjamin 2008, 35). But there is a paradox at work, as this approach delivers its impact “precisely on the basis of the most intense interpenetration of reality with equipment” (35). I call this notion the dialectic of mediation; in filmmaking, the poison has become the cure, as that which has endangered the aura of the live event—technological mediation—becomes the same means by which its recovery is attempted.

[1.8] Not only is montage technique seen as a compensatory strategy, its application also has ontological consequences. Benjamin argues that what occurs on set—actor’s performances—are not in themselves works of art. Rather, he writes, “the work of art is created only by means of montage” (29). Filmmaker Robert Bresson elegantly makes much the same point:

My movie is first born in my head, dies on paper, is resuscitated by the living persons and real objects that I use, which are killed again on film but, placed in a certain order and projected onto a screen, come to life again like flowers in water. (quoted in Ascher and Pincus 1999, 346)

While Bresson does not explicitly evoke the work concept as Benjamin does, his point is much the same: film emerges only as the director takes hours of rough material and crafts the finished product, the work of art. The director is a sculptor and his clay is film stock.

[1.9] Gould saw similar potential in the tape splice; in his writings, he argues that not only can studio technology bridge the distance between artist and audience, but its application also transforms studio recording into its own artistic medium, distinct from concert performance. While Gould stops short of an ontologically tinged discussion of the distinctions between recording and concertizing, perhaps nowhere does he draw the filmmaking/recording analogy more clearly than he does in his 1974 article, “The Grass Is Always Greener in the Outtakes.” In the following quote, he makes it clear that he compares the recording musician to a movie actor, and the studio microphone to a film camera:

Let us assume that . . . some artists really do underestimate their own editorial potential, really do believe that art must always be the result of some inexorable forward thrust, some sustained animus, some ecstatic high, and cannot conceive that the function of the artist could also entail the ability to summon, on command, the emotional tenor of any moment, in any score, at any time—that one should be free to “shoot” a Beethoven sonata or a Bach fugue in or out of sequence, intercut almost without restriction, apply postproduction techniques as required, and that the composer, the performer, and above all the listener will be better served thereby. (Gould 1984, 359)

[1.10] Should we accept Gould’s narrative? How closely does his process resemble that of a filmmaker? Do Gould’s studio recordings employ Eisensteinian intellectual montage? To riff on Benjamin: for Gould, is the work of art produced only by means of montage? As I will show in the following analysis of another of Gould’s recorded performances, his words and actions do not always correlate unproblematically, as they seem to do in the example of the A-minor Fugue. It will become clear that the recording/filmmaking analogy does apply, and that the dialectic of mediation is operative (my hunch is that both of these statements would be true, at least to a degree, in all instances of edited recording). However, the bar that Gould sets is somewhat higher than the mere application of montage technique and the dialectic of mediation. Two questions are at the crux of this investigation: At what point does the musical interpretation emerge? And what consequences does this emergence have on the performer’s and listener’s understanding of the work’s ontological state? I will demonstrate below that a “weaker” sort of montage technique may indeed be used to build up the final studio product, but that a preexisting vision of the work guides the process. Montage technique in the “stronger” sense, as theorized by Eisenstein, does not appear to be operative in the recording discussed below. At the close of this essay, I will draw what conclusions I comfortably can in light of this new information.

Part 2. Gould’s recording of a Brahms Ballade: background information and critical approach

[2.1] Throughout most of the 1970s, Gould made his recordings in his hometown of Toronto, in a studio installed at Eaton Auditorium.(5) By the end of 1980, however, a change in ownership of Eaton necessitated that Gould move back to the recording studios of New York City, where his first major-label records had been made. Venue was not the only aspect of Gould’s recording process that changed; upon his move back to New York, Gould began recording with digital equipment, which was then a new technology.(6) In order to navigate these changes, Gould was assigned a new producer, Samuel Carter.

[2.2] There are some terms pertinent to the standard recording process that the reader will find helpful in order to follow the ensuing discussion. None of these terms are unique to Gould, but where appropriate I have clarified his particular understanding of a term. Take: Gould uses this term to describe either a complete performance of a piece or movement, or an attempt to replace a trouble spot in a complete piece or movement. Insert: This term generally refers to a small portion of music recorded to replace a passage identified as problematic in a piece or movement. Studio Talk-Back: Also commonly referred to as “studio monitoring,” the talk-back is a means of communication, present in nearly all professional studios, between the control room and studio floor (or “tracking room”). In Gould’s case, speakers were generally placed on the studio floor. These speakers are fed from the recording console, through which the engineer or producer (by means of a built-in microphone) can not only speak to the performer, but can also play “feeds” (defined below). The performer, in turn, speaks through the microphones set up for the recording itself—no additional microphones are needed on that end. Feed: Also commonly called “pre-roll,” a feed is a short bit of music played over the talk-back system that helps performers place themselves back into the musical moment—to be able to match tempo and volume—when creating inserts. Coverage: This term, also commonly used in filmmaking, refers to the creation of options for later editing. The performer and producer want to be sure that they have obtained useable material for each and every note in a piece or movement, so that every passage is “covered.”

[2.3] In what follows, I closely examine Gould’s 1982 recording of the Ballade, op. 10, no. 1 by Johannes Brahms (Gould 1992b).(7) I have chosen this particular piece for an entirely practical reason: I was able to obtain several sources unavailable for most of Gould’s recorded oeuvre that help tremendously in unraveling the specific process for the recording. I employ three primary sources for this investigation: the complete studio outtakes for the recording;(8) a copy of Gould’s marked-up score for the piece, accessed through the Gould Archives (Gould 1982b); and a copy of the producer’s log for the recording session (Carter 1982). These sources each provide certain bits of information, but also have their shortcomings. I will also employ a fourth resource, my own re-creation of Gould’s finalized performance of the piece; this will be explained below.

[2.4] Studio outtakes: The complete studio outtakes allow a listener to hear everything that occurred on the studio floor while the recording machines were running. These include two complete takes of op. 10, no. 1; all attempts at inserts; and a good deal of studio chatter between Gould and Carter. Sometimes this studio chatter is quite illuminating in terms of how the producer and performer viewed various takes. However, many—if not most—important decisions were made either in the control room, when the recording device was not running, or after the recording session had wrapped. These decisions include the rationales for choosing one basic take over another, for why certain passages were identified as requiring correction by means of an insert, and for choosing a particular take of an insert. There is no sure way to know how long these conversations between Gould and Carter lasted or to what extent Carter’s input was taken into consideration. Despite these shortcomings, there is no better resource for gaining an inside look at how Gould went about making this recording.

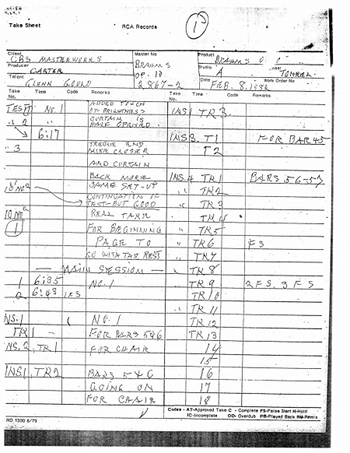

Image 1. A page from the producer’s log for Gould’s recording of the Ballade, op. 10, no. 1 (Carter 1982, 1). The handwriting is that of producer Sam Carter.

(click to enlarge)

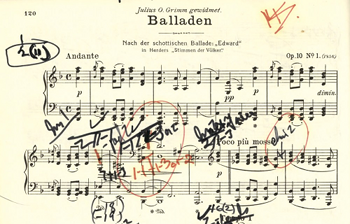

Image 2. Gould’s annotated copy of Brahms’s Ballade, op. 10, no. 1 (Gould 1982b, 120–22). Annotations pertain to Gould’s 1981 recording of the work.

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[2.5] Producer’s log: Image 1 presents a page from the producer’s log for Gould’s recording of the Ballade (Carter 1982, 1). The handwriting on this document is that of producer Carter. This sheet lists each take and occasionally provides a useful note for a take. For example, Carter writes that Insert 2 was created “FOR CHAIR,”(9) an indication that Gould’s (in)famous piano chair made excessive noise during this particular passage.(10) As the session continued, Carter’s comments grew less and less in-depth, so this document is not of tremendous value to my investigation. Nevertheless, it does provide a few key bits of evidence.

[2.6] Gould’s annotated score: Image 2a–c presents Gould’s annotated score for the Ballade (Gould 1982b, 120–22). It is clear that Gould’s notes were made on several different occasions: it is likely that Gould made some notes while in the studio in New York and more back home in Toronto.(11) Such scores, many of which are held in the Gould Archives, are a valuable resource, but not without their shortcomings. It is important to keep in mind that Gould never did his own editing; therefore, any given annotation merely represents his wish for the location of a tape splice, not its actual location. The final splicing scheme was determined by the engineer or producer for the particular project. In this case, it is most likely that Gould communicated his wishes to Carter by phone, who then executed the actual splicing scheme with the Sony PCM-1610. As the reader can also see, this score presents a researcher with another obstacle: Gould’s handwriting—especially on the third page—is extremely messy, bordering on illegible.(12) However, despite these obstacles, this document is a valuable resource for deciphering (approximately) where edit points are located, which takes Gould preferred, and occasionally other bits of pertinent information.

[2.7] My re-creation of Gould’s finished performance of op. 10, no. 1: Because of the shortcomings of these various sources, serious obstacles remain to making confident claims about the final splicing plan for this (or any) recording. When done well, tape splices and digital edits are not hearable. And Gould’s score, at best, merely puts us in the neighborhood of a given splice. In order to overcome these obstacles, I set out to produce a re-creation of the master version (the final performance as released on CD and record) of Gould’s recording of the Ballade. I posited that if I could take the raw material—the complete take used as the main source for the master and the various attempts at inserts—and edit together a performance that matches the version released on CD and record, I would know as definitively as possible which takes participate in the master and where the splice points occur. Accomplishing this, in turn, would allow me to make secure claims about the makeup of at least this one recording, something that (to my knowledge) has not previously been possible.

[2.8] My process was as follows. I loaded the master track into ProTools, a commonly used Digital Audio Workstation (DAW), panning it to play through the left channel. Next, I loaded Take 2 (the complete take that forms the backbone of the recording—more on this below) into ProTools and panned it to play through the right channel. I aligned these tracks to be synced from the beginning to the first splice point in measure 5. From there, my re-creation was assembled through a time-consuming process of trial and error. I placed each insert into a separate track, also panned to play through the right channel, and experimented with the “in” and “out” point until they, too, synced with the master. I eventually arrived at what I believe to be an accurate re-creation of Gould’s splicing scheme.(13)

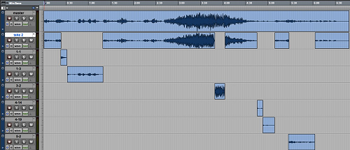

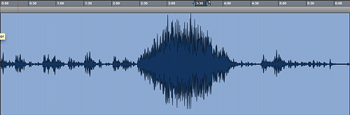

Image 3. Screenshot of ProTools file from my re-creation of Gould’s performance of the Brahms Ballade

(click to enlarge)

Audio Example 2

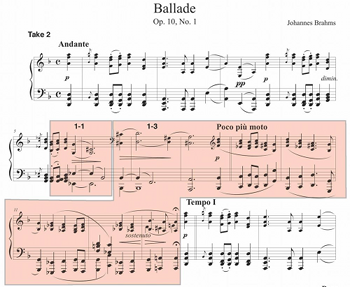

Example 2. Complete score of Brahms Ballade op. 10, no. 1, showing Gould’s finalized splicing scheme for his 1981 recording of the work

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[2.9] Image 3 is a screenshot of the ProTools file that contains my re-creation of Gould’s performance of the Ballade. The top track is the master; I have panned it to play through the left channel. Directly below this is Take 2, the complete take that was the basis for the master, which has been panned right. Below Take 2 are six additional tracks; these contain the inserts that participate in the master. These have been named with Gould’s usual numbering system and are also panned right.(14) I have arranged the six inserts in temporal order: Gould recorded 1-1 (“Insert 1, Take 1”) first, 1-3 (“Insert 1, Take 3”) next, and so on. Audio Example 2 presents a recording of my re-creation. I invite the reader to listen, noting how closely the two channels (master on the left, re-creation on the right) match.(15)

[2.10] I should make clear that in the early 1980s, this type of Digital Audio Workstation had not yet been created. Gould’s producers would not have edited in this manner, nor would they have had access to this sort of visual representation of the music. Be this as it may, viewing Gould’s performance of the Ballade in this manner is rather informative in itself. At a glance, it is easy to see that the original take that forms the backbone of the master (Take 2) was used extensively but was bolstered by six inserts. This image implies that the ultimate outcome of Gould’s editing, at least in this case, is a matter of improving one generally good take with a few inserts, as needed.

[2.11] Example 2a-c reproduces the score of op. 10, no. 1, on which I have indicated the final splicing plan. As with my ProTools file, I have used Gould’s usual numbering system to label takes and inserts. With the archival documents in hand and the final splicing plan revealed, I can posit answers to many questions that were previously unanswerable. What were the reasons for deciding to create inserts for various passages in the piece? Were these technical concerns or interpretative issues? In the process of making inserts, did Gould try out differing interpretations? Answering these questions will help us to understand not only Gould’s studio practices but his thought process as well.

Part 3. Gould’s recording of a Brahms Ballade: the recording session

Audio Example 3

[3.1] After sound-checking the piano, studio, and microphone placement, Gould played the complete movement through. His comments after Take 1 can be heard as Audio Example 3.

That was a hell of a basic take. I think it’s great. I’ll do it one more time but... There are lots of little things, but... It’s super. It had great character.(16)

This quote makes a few things clear. When evaluating this basic take, it was the overall “character” that mattered most. By “lots of little things,” Gould clearly means spots where an insert might be needed, but these are not of major concern at this point; the “little things” can be fixed so long as the character of the take is inspired.

Audio Example 4

[3.2] The second take is slightly slower than the first, but not noticeably so (Take 1 clocked in at 6:31, Take 2 at 6:39), and also quite lovely. After this take, Gould asks, “How about that?” to which Carter replies, “That’s beautiful... very beautiful take.” At this point, the session tapes do not help much as Gould and Carter quickly decide that one or the other take will work (Gould: “Let’s listen to both of them, I think”) as a basic take, and Gould leaves the piano to join Carter in the control room in order to listen to both complete takes. Without access to the conversation that occurred in the control room, I do not know why Take 2 was chosen over Take 1. Five passages were identified as requiring repair by means of inserts. Carter then set about cueing up feeds for each trouble spot as Gould headed back to the studio floor. I will discuss each of these problematic passages in turn. (Take 2 in its entirety has been provided as Audio Example 4.)

Audio Example 5

[3.3] Inserts 1 and 2: The producer’s log indicates that Insert 1 was created to replace “BARS 5+6.” This passage was identified as a trouble spot because of a technical issue with the piano—in Take 2, there is a buzz as Gould releases the

[3.4] As Ex. 1 indicates, another insert was used to replace m. 6.4 to the pickup to m. 14. This was identified as a trouble spot, according to the producer’s log, “FOR CHAIR.” Indeed, in Take 2, one can detect a slight bit of background noise—a sort of “rustling” or “creaking”—around mm. 9 and 10. For continuity’s sake, Gould and Carter must have felt that they would be better off replacing the entire phrase from mm. 9 through 13; they also ended up replacing the cadential gesture in mm. 7 and 8 that lies between the passages flagged for Inserts 1 and 2.

[3.5] The passages replaced by both Insert 1 and Insert 2 became linked together in the recording process. Immediately after playing 1-1, Gould announces that he would like to try Insert 2. Without hearing a feed, Gould plays from the pickup to m. 9 to the pickup to m. 14. He immediately expresses dissatisfaction with this take. Gould makes reference to a conversation he must have had in the control room with Carter. Gould seems confident that 1-1 took care of the trouble spot in m. 6, but says, “Let’s try Insert 1 again just for safety’s sake.” Carter seems to understand that Gould is going to “go on into the other area,” meaning the measures they had identified as needing to be replaced with Insert 2. 2-1 would be the only take labeled with a “2” as its first number, meaning that the trouble spot identified for Insert 2 became subsumed into Insert 1.

[3.6] For 1-2, Gould listens to the feed, starts at m. 4.4, and stops on the downbeat of m. 14. He remarks: “I have a feeling that the spot at bar 6 was a little bit louder than it had been before. Let’s try one more time.” This brings us to 1-3, which was included in the master. For this take, Gould again plays through the passages that were identified for Insert 1 and Insert 2—from the pickup to m. 5 up to the pickup to m. 14. “Well that certainly got it” was Gould’s immediate reaction to this take, which was used to replace the music from m. 6.4 up to the pickup to m. 14.

[3.7] In Insert 1-3, Gould takes a bit longer on the cadential gesture in mm. 6–8, but the two performances (Take 2 and 1-3) of the subsequent phrase, mm. 9–13, are almost identical in tempo and affect. The chair stays quiet this time. Perhaps Gould decided to approach the half-cadence at m. 8 a bit more deliberately than he had in Take 2, but given that the subsequent phrase is so similar to the original take, it can be assumed that these inserts were made primarily for the sake of technical issues—the buzz in the piano in m. 6 and excessive noise from Gould’s chair around mm. 9 and 10. The fact that the insert covered more measures than these can likely be attributed to retaining continuity of the phrase or for ease of editing.

[3.8] Insert 3: After the passages replaced by 1-1 and 1-3, Gould performs a long stretch of the Ballade in which no problems are identified—there would be no inserts from the pickup to m. 14 until m. 45.3. The producer’s log indicates that Insert 3 was needed “FOR BAR 45.”

[3.9] After arriving at satisfactory takes for the passages targeting for Inserts 1 and 2, Gould indicates that he is ready to move on, commenting to Carter, “I’ll show you a pair of minus a halfs.” The tape cuts off at this point, an indication that Gould again left the piano to join Carter in the control room. As Image 2c shows, the pianist wrote “-1/2” underneath mm. 45 and 46, but it is unclear what he meant. He seems to have identified beats 45.4 and 46.1 as problematic, and Insert 3 eventually replaced mm. 45.3 to 48.3.

[3.10] A thorough structural and hermeneutic analysis of this Ballade is beyond the scope of this essay. That said, my analytical view of the piece aligns closely with that presented in Hastings 2008. In her analysis, Hastings takes as a starting point the generally accepted view that Brahms’s Ballade began life as a setting of the eighteenth century English folk ballad “Edward.”(17) Hastings identifies the piece’s first phrase (mm. 1–8) as depicting the voice of Edward’s mother, and the second phrase (mm. 9–13) as a response in Edward’s voice. I accept that we could call this second phrase “Edward’s music.” I agree with Hastings, further, that the piece’s middle section (mm. 27–59) dramatically depicts Edward’s murder of his father.

[3.11] The dramatic climax of the piece occurs near m. 45. After a relentless buildup of tension and veiled references to Edward’s music in mm. 27–43, Edward’s tune emerges clearly at m. 44, placed an octave above its original statement (at m. 9) and given a thicker harmonization. The obsessive triplet figure that saturates mm. 27–43 remains in the left hand from m. 44 forward, providing the music with a sense of continued momentum. In the hands of most pianists (besides Gould, I sampled recordings by Rubinstein, Sokolov, Schliessmann, Kempff, and Biret), the passage receives a sustained dynamic apex coinciding roughly from the downbeat of m. 38 to the downbeat of m. 49. Many performers (Biret especially) are sensitive to the numerous crescendo markings, giving each downbeat that follows a bit of extra weight. Some performers begin to pull back the dynamic a few beats before the downbeat of m. 49, but for most, the intensity does not decrease noticeably until just after this arrival point.

Image 4. Screenshot of ProTools file from Gould’s performance of the Ballade in Take 2 (the passage that will be replaced by Insert 3 is indicated by the split arrow)

(click to enlarge)

[3.12] As he performed the passage in Take 2, Gould’s interpretation differs somewhat from this typical performance of the Ballade: he builds slowly through the middle section, reaching a clear apex at m. 40.1. From there, he allows the dynamic to fall off more quickly than most performers do; a decrease in volume—not perfectly linear but nearly so—occurs over the span of the next eight measures. Image 4 is another ProTools screenshot that helps to identify exactly where Gould placed the dynamic high points in Take 2. The prolonged dynamic high point just short of 3:30 coincides with mm. 39.1–49.1: Gould takes the crescendo marking into the fortissimo at m. 40 rather seriously.(18) One can see secondary moments of dynamic intensity, but the overall shape of the waveform clearly shows that the volume decreases after this ten-measure span. In Image 4, I have used a split arrow at the top of the image to indicate the passage that would ultimately be replaced by Insert 3. It is easy to see that this passage was taken considerably more softly than the dynamic apex around m. 40. Gould’s performance here breaks, if only subtly, with the typical interpretation of this Ballade.

Image 5. Screenshot of ProTools file, finished master of the Ballade (the passage that was replaced with Insert 3 is indicated by the split arrow)

(click to enlarge)

[3.13] Take 2 must also have deviated from Gould’s own internal hearing of the Ballade. Image 5 is a ProTools screenshot of Gould’s performance as it appears in the master. Once again I have indicated with a split arrow the area that was replaced by Insert 3. This passage, in comparison with Take 2, has been increased in volume relative to m. 40. Although m. 40 is still the dynamic apex of the performance, the decrescendo is no longer so extreme as in Take 2. Analyzing the music in this way suggests the meaning of Gould’s “-1/2”: something to the effect of, “I played this passage just a bit more quietly than I meant to; I would like to create an insert that increases the volume of this passage by about a half dB.”(19)

Audio Example 6

[3.14] When the tape resumes after Gould’s visit to the control room to consult with Carter, the producer calmly intones, “This is Insert 3 for bar 45, Take 1,” then begins the feed. Gould listens to the feed, and plays from at m. 44.4 to the downbeat of m. 48. He stops abruptly and asks Carter, “How did that look?” Carter responds: “It looked OK.” Gould expresses that he would like to do one more take. For 3-2, Gould listens to the feed and plays from m. 45.1 to m. 49.1. He seems pleased, immediately commenting, “No question about that, eh?” The following conversation ensues (mm. 45 through 49.2 in 3-2, followed by studio chatter, is provided as Audio Example 6):

Carter: I think that’ll work fine. It still reads a little lower but I think if we take the several notes we’ll be fine.

Gould: Sure, and we can make a slight adjustment.

Carter: We can make... I can make good adjustments now on the Sony too so it’ll be OK.

This studio chatter supports my assertion that this passage was identified as needing replacement because it had been played too softly. After 3-1, Gould asks “How did that look,” an indication that Carter was monitoring volume meters on either the mixing board or the Sony PCM. After 3-2, the successful take, Carter says “It still reads a little lower,” but also saysthat a correction can be made in the editing phase.

Audio Example 7

[3.15] There is virtually no difference in the two interpretations of mm. 45.3–48.3 (Take 2 and master, presented as Audio Example 7). The timing is the same and there is no noticeable difference in terms of articulation or phrasing. There is no way to establish a difference in absolute volume between the two recordings; the best I can do is compare the volume of this passage against the volume of its surroundings, which is why I provided two ProTools screenshots of the passage (Images 4 and 5).(20)

[3.16] There are still a few unanswered questions in regards to this insert. I do not know why, if the Sony is capable of slight volume adjustments in the editing phase, they did not simply keep the original performance and alter the volume mechanically. I also do not know if “slight adjustments” were made after all to 3-2, either when it was spliced into the final performance or at the final stage of production, the mastering phase. Nevertheless, it seems safe to conclude that Insert 3 was created in order to fix the dynamic of the passage; my conclusion is that, as originally performed in Take 2, it did not quite match Gould’s internal audiation.

[3.17] Insert 4: Immediately following the exchange discussed in paragraph 3.14, Carter says, “This is Insert 4 for bars 56, 57, Take 1.” This indicates that they were comfortable with Insert 3 and wished to move on to the next trouble spot. The passage identified for Insert 4 is very short: just the two-chord gesture from mm. 57.3–58. However, Gould winds up replacing more than just this gesture; he also replaces what I call the “turnaround,” mm. 58.2–59.2. Although Gould plays through mm. 57.2–59.2 in every attempt at a retake, this passage became divided into two segments in the editing phase (“two-chord gesture” and “turnaround”); therefore, I will discuss these two short segments separately, starting with the two-chord gesture in mm. 57.2–58.1.

[3.18] Two-chord gesture: Gould’s motivation for replacing the music in Take 2 seems to be twofold: (1) there is a slight rolled effect on the F-major chord on the downbeat of m. 58, and (2) Gould played this passage more loudly than he intended. Gould’s comments support this explanation: after 4-5 he says, “The F-major chord was a little too loud. In my nervousness to make sure that they all spoke evenly I got ’em to speak evenly but at the risk of being a little louder than I wanted for the resolution.” Even for a pianist of Gould’s talent, an even attack at a very low dynamic seems to present a technical challenge.

[3.19] Turnaround: This passage was changed interpretively in the process of recording inserts. In the master, Gould plays the music at mm. 58.2–59.2—the diminished chord and downward scale passage that acts as a turnaround leading into the piece’s recapitulation—quite a bit more slowly than he did in Take 2. This is a key moment in the piece’s drama. As Hastings argues, here an imaginative listener can picture Edward slowly lowering his hands, loosening his grip on the bloody sword as he looks upon his now-dead father (Hastings 2008, 92). Whether Gould had this mental picture in mind certainly cannot be known, but it seems likely that Gould understood the weight of this moment and decided to interpret it with more gravity than he had in Take 2. Some recorded comments support this assertion. After 4-2, Gould can be heard saying, “That was a little too slow, I think.” The way he stresses the word “too” makes it clear that he wanted a slower interpretation than he delivered in Take 2, but not quite so slow as he had just played. Although there is no way to know whether the interpretive issues were discussed by Gould and Carter at some point in the control room, it seems safe to conclude that mm. 57.2 through 59.2 were identified as a trouble spot for a combination of piano technique (the two-chord gesture) and interpretive concerns (the turnaround).

Audio Example 8

[3.20] Simple though these passages look on paper, they caused Gould a great deal of trouble, requiring nineteen takes in all to repair. The first few takes were rejected for reasons of either volume or tempo. After nine attempts, the volume does not seem to match what he is after (either Gould sensed this himself, or Carter commented that the meters did not read as they should). After 4-10, Gould begins to complain about a mechanical issue he is having with the piano: he is hearing a sympathetic

in every respect it’s good except that I keep getting this bloody

G♮ sounding through. I mean I hear it for about two-thirds of the length of the tone and then it lets go. It’s something in the piano. I can only hope to get lucky.

Finally, in 4-19, Gould seems to get lucky. After this take, he does not comment on its quality, but simply says “All right, let’s do the last one then,” an indication that he is ready to move on to Insert 5.

[3.21] 4-14 and 4-19 were both included in the master: 4-14 was used for the turnaround—this take apparently got the tempo and expression just right—while 4-19 was used for the two-chord gesture. While 4-19 seems to have been needed for reasons of piano technique, in 4-14 Gould plays the turnaround gesture differently than in Take 2; this is the first truly noticeable interpretive change created in the editing process. Even here, the interpretive change is small-scale, contained to just two notes: in 4-19, the F and E at m. 58.1 and 58.2 are drawn out considerably compared to Take 2.

[3.22] Insert 5: The producer’s log for Insert 5 simply states “BAR 64.” This insert seems to have been created in order to repair the left-hand F at m. 64.3, which came out noticeably quieter than its surrounding context in Take 2—but in the process of fixing this note, Gould slightly alters his interpretation of the low C and A on m. 64.4. In Take 2, Gould pedals into the pianissimo diminished chord at the downbeat of m. 65; this has the effect of giving the low A and C a different affect than the other left-hand (incomplete) triplets in this passage. Comments made over the talk-back lead me to believe that Gould and Carter did not discuss this pedaling choice while conferring about Take 2, but that Gould independently decided to eliminate the pedal from this passage.

Audio Example 9

[3.23] The prepared feed for Insert 5 begins at m. 62. In each re-take, Gould plays along a bit, pauses, then circles back to m. 62.4 to try the take in earnest. For most of these takes, Gould continues playing well past the trouble spot—in 5-2, he even plays through the movement’s end and into the first few beats of op. 10, no. 2—but the insert included in the master does not include this much music. The first two takes go well; after 5-2, Gould states confidently that “we definitely got it between the two of them.” Carter, however, is not so certain and the following exchange ensues (provided as Audio Example 9):

Carter: Glenn, my only question is... I keep having kind of an annoying feeling [that] the right hand is a little more legato [in m. 64]. Now, I couldn’t exactly swear to it.

Gould: No, you’re absolutely right. I was deliberately... Well, I don’t know if it’s the right hand so much what I was doing on the basic take was pedaling into the pianissimo diminished chord and I was trying not to do that because it spoiled the sardonic effect. I was actually trying to pick up two points for one.

Carter: So that is what you wanted then?

Gould: Quite deliberate.

What Carter was hearing, as Gould notes, was not a change in the right-hand articulation, but in the left: in 5-2 he plays the C–A gesture as short-long, rather than Take 2’s more legato interpretation (long-long).

[3.24] Although Gould seems to like 5-2, he clearly decided to give himself more options in the editing phase. He made two more recordings of the passage, for a total of four takes of this insert. In both of the remaining takes, he performs the C–A gesture at m. 64.4 in a similar manner to 5-2, articulating the C cleanly and elongating the A slightly. 5-2 ended up being the take of choice, replacing mm. 63.4–68.2, but judging from Gould’s marked-up copy of the score (Image 2c), he had a good deal of trouble settling on a take he preferred here. There are multiple spots where something was written and crossed out, and there is a note—probably to himself—pertaining to the choice of take. Gould wrote on the left side of the page, “Char[acter] is diff[erent] (as S[am] C[arter] observed) if this does not work, l[ea]v[e] 1 in; however, artic[ulation] is much better in 5-2” (Gould 1982b, 121). Gould clearly liked the articulation of 5-2, but was not certain that it would fit in with the surrounding material.

[3.25] I cannot be sure who made the final call regarding Insert 5; perhaps Gould had chosen it by the time he spoke on the phone with Carter to communicate his splicing plan, or perhaps Carter made the determination himself. It is also noteworthy that the actual out point of the insert, which occurs just before the right-hand F at m. 68.3, is not one of the choices marked on Gould’s score. Presumably, Carter chose this point for ease of splicing, cutting back to Take 2 a beat sooner than any of Gould’s options. In Take 2, Gould plays this two-note gesture (m. 68.2) as short-long, matching the similar gesture at m. 64.4, but he does the same in 5-2. There seems to be no technical or interpretive reason, therefore, to splice a beat early. Perhaps it was a matter of finding the space between the notes to make the splice, with the long G# perhaps making it difficult to fit in a splice just before the last beat of m. 68. Take 5-4, which went unused, was the last bit of material recorded for op. 10, no. 1, as Gould and Carter promptly moved on to op. 10, no. 2.

Part 4. An Evidence-Based Rejoinder to Gould’s Narrative

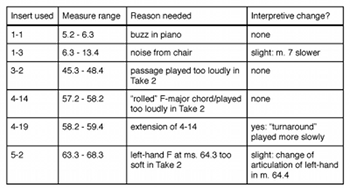

Table 1. Inserts for Take 2 of the Ballade, reasons they were needed, and any resulting interpretive changes

(click to enlarge)

[4.1] After recording and editing the Ballade was complete, very little was changed from Take 2 to the master in terms of musical interpretation. Table 1 shows each insert, why it was needed, and any resulting interpretive change from Take 2. Of the six inserts, three (1-3, 4-19, and 5-2) make an interpretive change. Of these, however, only one (4-19) makes a change of any significance, and this is confined to just two pitches. In all other cases, it seems that Take 2 did not match Gould’s own internal hearing of the piece, and that retakes were used not so much to try out different interpretations but, rather, to more accurately capture what he intended to do in the first place. Gould occasionally made technical errors, and it seems that he sometimes made interpretive “errors” also. Even in the case of Insert 4, Gould did not try out different interpretations in the process of making inserts. In all nineteen takes, he performs the turnaround gesture at the same slow, grave tempo.

[4.2] Gould put his recordings together like a film director would a film, synthesizing interpretively dissimilar takes in order to craft a performance that did not—and perhaps could not—take place in real time. This interpretation, moreover, may not have been envisioned in advance of the recording date. Critic Richard Kostelanetz, for instance, wrote that “Gould will record several distinctly different interpretations of the same score and then pick judiciously among the available results, even splicing two originally contrary renditions into the final integral version” (Kostelanetz 1983, 132). There is a significant difference, however, between using editing to correct problems with an interpretation that more or less stands on its own and using editing to synthesize or create an interpretation based upon what Gould often referred to as the “post-taping afterthought” (Gould 1966, 53). The first approach has been commonplace since the advent of magnetic tape as a recording medium,(21) while the second engages with practices that—to paraphrase Eisenstein—compensate for the loss of presence and—to paraphrase Benjamin—elevate film to an independent art form.

[4.3] As my research shows, Gould’s recording of this Brahms Ballade cannot be said to be a case of Eisensteinian intellectual montage. It would be far more accurate to say that Gould used splicing to correct technical issues and musical balances, perfecting a preconceived—if imperfectly executed—interpretation rather than crafting something emergent from the raw material. Indeed, in email correspondence with me, Gould’s long-time engineer, Lorne Tulk, firmly denies that Gould crafted interpretations via editing.(22) Tulk writes:

Glenn’s reasons for any edit was [sic] invariably to repair a problem. That might be a slurred note, or a hick-up [sic] or just an improper note (he did occasionally do that!). He seldom if ever used editing for interpretation, that was his domain . . . out there at the piano. (Tulk 2012–14)

Further, Tulk asserts that “if Glenn wanted to try different interpretations, he would make a second entire ‘version’ of the piece or movement” (Tulk 2012–14). He would go through the process of creating inserts for each version, treating them separately for the entire process. Gould would choose one or the other, but he would not routinely combine the different interpretations.

[4.4] If we accept Tulk’s account, and if we generalize based on my investigation of the Brahms Ballade, the example of the A-minor Fugue discussed at the beginning of this essay now seems like a rare exception rather than the rule. That said, Paul Sanden has recently uncovered another Gould recording, of the third movement of Beethoven’s Pathétique Sonata, wherein differing interpretations seem to have been combined as they were in the A-minor Fugue (Sanden 2014). While I believe Tulk and the evidence provided by my investigation of the Brahms Ballade, my conclusions are necessarily provisional and open to challenge based on further research. In the end, we can only build a complete picture of Gould’s work one piece at a time, and I want to state unequivocally that such research must not be based on what was written or said by Gould and others, but must be based on what actually occurred in the recording studio. Like many literary narrators (Holden Caulfield comes to mind), it seems that Gould was a rather unreliable reporter of the events of his own life.

[4.5] I began this essay by discussing what I call the problem of loss of aura: the idea that something goes missing when the live becomes canned. There is something special in the live performance, the thinking goes, and recording and playback technologies are largely focused on trying to compensate for the loss of this element. Like Eisenstein and other filmmakers, recording artists and producers are focused on using technology in order to bring an authentic experience—a simulacrum of the live performance—to those listening from the comfort of home. Was this Gould’s aim?

[4.6] In a 1974 interview, Gould was asked if the pianist ever “[felt] the need to have direct communication with the public”; he responded, “no, I don’t. I feel in fact that I have a much more direct means of communication through recording” (Monsaigneon 2002). The interviewer suggests that musical communication is a function of liveness and presence, but Gould’s response suggests that it is not. During the same interview, Gould states his goal as a recording artist:

If there’s one thing one does attempt to do in making a recording it’s to make one thing perfectly clear. That one thing being one’s concept of the work, permanently clear to everyone who cares to listen to it. (Monsaigneon 2002, emphasis added)

Gould does not say that the goal of making a recording is to return the listener to the concert hall. Indeed, on another occasion, Gould claims that the concert hall is “precisely what the recording got you out of. To put you back there and say that’s the ultimate achievement seems to me to defeat the purpose of the recording” (quoted in Cott 1984, 89). Tulk confirms this statement, writing “when Gould made the move from ‘live’ stage to the ‘electronic’ stage, it was absolute. I don’t believe he ever, in any way, tried to duplicate anything” (Tulk 2012–14).

[4.7] The recording studio is a compensatory strategy, but not in the way we might expect. Eisenstein admits that what he called “presence” is threatened by technology. Gould, however, denies this premise. For all that might be gained with live performance, there are obstacles to conveying musical works in a live setting: the potentially distracting element of the performer, performers’ mistakes, poor acoustics, external noise, inconsiderate audience members. As Gould biographer Kevin Bazzana writes, “the projection of pieces to a dispersed crowd in a large space was, for [Gould], the source of unnecessary nuances that had no justification in a structural event” (1997, 243). The musical work was Gould’s chief concern, not human-to-human contact, presence, or “liveness.” Via the recording studio, Gould sought to communicate the eternal work, not the realized moment or means of its re-creation.(23) For Gould, what Benjamin refers to as aura, and what the pianist might think of as “liveness” or “presence,” lies not in the moment of performance, but in the work itself.

[4.8] By removing the work from the imperfections of the concert hall, recording allows musicians and listeners to achieve an intimacy with the musical work of art. “The true recording artist,” writes Gould,

is someone who is looking at the totality—see[ing] it so clearly that it doesn’t matter if you start in the middle note in the middle movement and work in either direction like a crab going back and forth. The mark of a true recording artist is an ability to be able to cut in at any moment in any work. (quoted in Bazzana 1997, 242)

With such a complete conception of the work in place, Gould was able to put the picture together by whatever means he pleased. Such an ability is, of course, much like that of the filmmaker, who is not expected to produce a compelling movie in one long shot. However, Eisensteinian intellectual montage has a rather particular purpose—translating the emotional impact of the live event for the screen. At least in the case of this Brahms Ballade, this is not the way in which Gould used the studio: he used the studio to flawlessly execute his conception of the work. For Gould, the work of art is not produced by means of montage, but it is thus preserved.

Garreth P. Broesche

4513 Hummingbird Street

Houston, TX 77035

dr.broesche@gmail.com

Works Cited

Ascher, Steven, and Edward Pincus. 1999. The Filmmaker’s Handbook. Plume.

Bazzana, Kevin. 1997. Glenn Gould: The Performer in the Work. Oxford University Press.

—————. 2004. Wondrous Strange: The Life and Art of Glenn Gould. Oxford University Press.

Benjamin, Walter. 2008. “The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility.” In The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility and Other Writings on Media, ed. Michael W. Jennings, Brigid Doherty, and Thomas Y. Levin, trans. Edmund Jephcott and Harry Zohn, 19–55. Belknap Press.

Bordwell, David, and Kristin Thompson. 2004. Film Art: An Introduction, 7th ed. McGraw Hill.

Broesche, Garreth. 2015. “The Intimacy of Distance: Glenn Gould and the Poetics of the Recording Studio.” PhD diss., University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Canning, Nancy. 1992. A Glenn Gould Catalog. Greenwood Press.

Carter, Samuel H. 1982. Producer’s log from recording session for Johannes Brahms’s Ballades, Op. 10. Columbia Records. Obtained from Library and Archives Canada. Series: official records. Item number: 57 27 1.

Cott, Jonathan. 1984. Conversations with Glenn Gould. Little, Brown and Company.

Culshaw, John. 1967. Ring Resounding. Viking Press.

Eisenstein, Sergei. 2010. Selected Works, Volume 2: Towards a Theory of Montage, ed. Michael Glenny and Richard Taylor, trans. Michael Glenny. I.B. Taurus.

Gould, Glenn. 1966. “The Prospects of Recording.” High Fidelity (April): 46–63.

—————. 1982b. Personal score of Brahms’s Ballade, Op. 10, No. 1. Obtained from Library and Archives Canada. Series: scores. Item number: S22-1.

—————. 1982a. Complete studio outtakes from recording of Johannes Brahms’s Ballades, Op. 10. The studio outtakes are from a set of CDs comprising the complete original audio from the recording session of 8 February 1982, presumably dubbed from analog tapes formerly in Gould’s possession and now among the holdings at the Glenn Gould Archives at Library and Archives Canada (the Glenn Gould Archives, MUS 109). I obtained my copy from a private source.

—————. 1984. The Glenn Gould Reader, ed. Tim Page. Vintage Books.

—————. 1992a. Glenn Gould Plays Bach: The Well-Tempered Clavier, Books I & II (The Glenn Gould Collection, Vol. 4). Sony Classical 88725412692, compact disc.

—————. 1992b. Glenn Gould Plays Brahms: 4 Ballades Op. 10, 2 Rhapsodies Op. 79, 10 Intermezzi (The Glenn Gould Collection, Vol. 12). Sony Classical 88725412902, 2012, compact disc.

Hansen, Miriam Bratu. 2008. “Benjamin’s Aura.” Critical Inquiry 34 (2): 336–375.

Hastings, Charise. 2008. “From Poem to Performance: Brahms’s ‘Edward’ Ballade, Op. 10, No. 1.” College Music Symposium 48: 83–97.

Kazdin, Andrew. 1989. Glenn Gould at Work: Creative Lying. Dutton.

Kostelanetz, Richard. 1983. “Glenn Gould: Bach in the Electronic Age.” in Glenn Gould Variations, ed. John McGreevy, 125-141. Quill.

Monsaigneon, Bruno. 2002. Glenn Gould: The Alchemist. Directed by Francois-Louis Ribadeau. 1974. Toronto, CA: Classic Archive. DVD.

Payzant, Geoffrey. 1983. “Yes, But What Is He Really Like?” in Glenn Gould Variations, ed. John McGreevy, 77-82. Quill.

Roberts, John Lee. 1983. “Reminiscences.” in Glenn Gould Variations, ed. John McGreevy, 227-251. Quill.

Sanden, Paul. 2003. “Glenn Gould and the Beatles: Creative Recording, 1965-1968.” MA thesis, University of Western Ontatrio.

—————. 2014. “The Creative Splice: Glenn Gould’s Recording of Beethoven’s Pathétique Sonata.” Unpublished paper delivered at the Annual Conference of the Canadian University Music Society, Brock University, May 28.

Schenker, Heinrich. 2008. The Art of Performance. ed. Herbert Esser. trans. Irene Schreier Scott. Oxford University Press.

Sterne, Jonathan. 2003. The Audible Past: Cultural Origins of Sound Reproduction. Duke University Press.

Tulk, Lorne. 2012–14. Email correspondence with the author.

White, Glenn D. and Gary J. Louie. 2005. The Audio Dictionary, 3rd ed. University of Washington Press.

Footnotes

1. Our awareness of some trick of mediation can alter our perception of it to a surprising degree. While I likely would not have noticed the change on my own, once alerted to it, the juxtaposition of differing interpretations now seems rather clumsy.

Return to text

2. The Glenn Gould literature, both primary and secondary, is full of discussions of the recording/filmmaking analogy. I will draw the reader’s attention to a few examples. Geoffrey Payzant brings up the analogy in Payzant 1983 (78), as does John Lee Roberts (1983, 261). Gould’s own thoughts on the analogy will be discussed further below (paragraph 1.9).

Return to text

3. Benjamin’s essay is more commonly referred to as “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction.” Here I use the title given to the essay by the editors of the essay’s most recent English translation.

Return to text

4. Close readers of Benjamin’s work might object that the conception of aura I employ in this essay is overly simplistic. As Miriam Bratu Hansen writes, “the narrowly aesthetic understanding of aura rests on a reductive reading of Benjamin,” and thus a conception of aura derived primarily from the “Artwork” essay “is not particularly helpful” (Hansen 2008, 337). I disagree with Hansen’s assessment, at least in regard to what extent an aesthetic understanding of aura may or may not be “helpful.” I would ask: helpful to whom and to what ends? My interest in this essay is not a discussion of Benjamin qua Benjamin. I have far more interest in the ways in which his ideas might prove “helpful” to a conversation about music and mediation than I have in unpacking every nuance of his complex intellectual legacy.

Return to text

5. For a detailed discussion of Gould’s studio at Eaton, as well as his usual recording process, see Broesche 2015, 181–202.

Return to text

6. The New York City studios where Gould recorded in the early 1980s (RCA’s Studio A and Columbia’s 30th St. facility) were outfitted with brand-new Sony PCM-1600 series recording devices.

Return to text

7. This recording (Gould 1992b) was made in RCA’s Studio A; the session began in the evening of February 8, but dragged on well past morning of the next day (Canning 1992, 48). The recording was released by CBS Masterworks on March 1, 1983, some five months after Gould’s death (Canning 1992, 193).

Return to text

8. See Gould 1982a. Although this recording was made digitally, the machine used (Sony PCM-1610) was apt to certain malfunctions. In order to ensure that the sessions would not be lost because of a malfunction, the session was also captured on a reel-to-reel analog machine. This copy was the one that Gould took home to Toronto with him to listen to the session tapes and create his splicing plan. It is clear from listening to the studio outtakes that they were dubbed from the analog tapes, not the digital copy, which caused a bit of trouble when producing my re-creation (discussed below).

Return to text

9. Quotes from the producer’s log (Carter 1982) are written in all caps; this is how Carter wrote on the sheets themselves. For minimal disruption, I will not cite each instance separately.

Return to text

10. For a discussion of Gould’s chair, see Bazzana 2004, 108–9.

Return to text

11. Gould’s usual practice, whether recording in New York or in Toronto, was to take a copy of the session tapes (more than one machine was always recording at once) to his home, where he would listen critically and devise a splicing scheme which he would then communicate to the producer, usually by phone (see Kazdin 1989, 30).

Return to text

12. Kevin Bazzana seems to have developed a talent for reading Gould’s handwriting, and he was gracious enough to help me transcribe/translate a few of the notes on this score.

Return to text

13. The reader might wonder whether my re-creation is indeed accurate. In other words, is my re-creation the only possible re-creation of the splicing scheme for this recording? While admitting the possibility that I could have erred—it was a very difficult task—I believe that I have determined the actual splicing scheme used for this recording.

Return to text

14. In Gould’s usual numbering system, the first number refers to the insert number, the second to the take number. This is how Gould annotated his personal scores and also how he referred to inserts over the studio talk-back system. For example, “4-14” refers to “Insert 4, Take 14.”

Return to text

15. While the two tracks match very well, the reader will notice some considerable differences in sound quality between the two channels. This is because, as noted above, the Master was recorded digitally while the outtakes were taken from an analog reel-to-reel backup. This explains the existence of “flutter” and “wow” in the right channel (see White and Louie 2005, 155-6 and 425). In addition, the outtakes have presumably never been mastered, another source of changes in the tonal and timbral qualities of these recordings.

Return to text

16. All studio chatter and references to studio outtakes are taken from the complete studio outtakes (Gould 1982a). For minimal disruption, I will not cite each instance separately.

Return to text

17. A translation of the original poem into modern English can be found in Hastings 2008 (96) or online here: http://www.poemhunter.com/poem/edward-edward-a-scottish-ballad/.

Return to text

18. Unfortunately, ProTools offers no means of including a mensural timeline along with the clock-time shown here.

Return to text

19. It is generally accepted by researchers in psychoacoustics that the Just Noticeable Difference (JND) for volume is 1 dB, twice the 1/2 dB discussed here (see White and Louie 2005, 207), but certainly, Gould’s ears were exceptional.

Return to text

20. Many factors are involved in absolute volume, such as the different levels of the source CDs and the impact that editing and mastering may have had on the overall volume of the master. Once again, the fact that the outtakes were taken from the reel-to-reel backup, and that they appear to be unmastered, presents a challenge.

Return to text

21. As legendary classical-music producer John Culshaw writes, “since tape can be spliced, the era of the ‘assembled’ performance had come into being almost before anyone realized the implications” (Culshaw 1967, 10).

Return to text

22. Lorne Tulk is one of Gould’s longest-tenured musical associates. Tulk and Gould met in the 1950s and began working together formally when Gould began making recordings at Eaton Auditorium in Toronto in 1971. Although they remained friends up until Gould’s death in 1982, Tulk did not participate in the late recordings Gould made in New York (including the Brahms Ballade). Tulk’s role was entirely technical, his primary job being to help set up and take down the recording equipment at recording sessions. He was also a frequent companion of Gould’s when, after a recording session had wrapped, Gould would listen to raw studio material at home with the purpose of devising a splicing plan. During these listening sessions, Tulk made splices of the backup tape in order to help Gould determine the viability of his wishes for the final splicing scheme (the master tapes were taken back to New York with Gould’s long-time producer, Andrew Kazdin). There is probably no one still living who knows more about Gould’s recording practices. I am extremely grateful for having been able to communicate with him—this research project would not have been possible without his help.

Return to text

23. My reader may note a similarity between Gould’s thinking and ideas expressed by Heinrich Schenker. For example, in the polemical opening sentences of Art of Performance, Schenker writes: “basically, a composition does not need a performance in order to exist. Just as an imagined sound appears real in the mind, the reading of a score is sufficient to prove the existence of the composition. The mechanical realization of the work of art can thus be considered superfluous” (Schenker 2008, 1). Gould’s studio performances seek, in a different way, to remove the performer from the equation; in his case, the listener rather than the score-reader is given a direct line to the work. For a discussion of the ways in which Schenker’s thinking might enrich my discussion of music and mediation, see Broesche 2015, 18–23. For a discussion of the problematic nature of Gould’s attempt to disappear into the work, see Broesche 2015, 124–7 and 170–7.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2016 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Michael McClimon, Senior Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

15744