Review of Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Julian Horton, eds. Rethinking Schubert (Oxford University Press, 2016)

Jonathan Guez

KEYWORDS: Schubert, music analysis, song

Copyright © 2017 Society for Music Theory

[1] In the last two decades, Schubert has come to occupy a central position in Anglo-American and European music theory and musicology.(1) That the composer should find himself in such a position may seem unsurprising to future historians of theory; after all, many of the recent shifts in academic musical discourse—the interest in sexuality and identity studies, the emergence of neo-Riemannian theory, and the revival of Formenlehre—would seem to have created the ideal soil for renewed interest in him to take root.

[2] And yet, the figure of Schubert is not at the “center” of some monolithic discursive field. Indeed, the very notion of centrality belies a vast array of diverse approaches to Schubert scholarship. There have been new theories, analyses, and interpretations of his works; updated biographies; histories of his political milieu and social circle; studies of his relationships and sexuality; renewed attention to documentary sources; examinations of his working habits; emphases on neglected repertoire; and more. As Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Julian Horton write in their introduction to Rethinking Schubert (RS), “the contemporary Schubert is vibrant, plural, transnational and complex” (10).

[3] Nowhere is the vibrancy of the current figure of Schubert more clearly on display than in Byrne Bodley and Horton’s recent tome, whose twenty-three essays reflect the fertile diversity of contemporary Schubert studies even as they promise to bear nourishing fruit. There is no question that, through subjecting “recurring issues in historical, biographical, and analytical research to renewed scrutiny,” RS does indeed “yield new insights into Schubert, his music, his influence and his legacy, and broaden the interpretative context for the music of his final years” (3).

[4] But the book is also representative of Schubert studies in that the level of engagement is uneven. To continue the metaphor: in this compendium-cum-arboretum, some essay-plants grow to majestic (and magisterial) heights, while others suffer from various ailments. Some are undernourished; more often, overgrown foliage renders their crowns opaque, permitting no light to shine through. Below, I discuss RS’s genesis and structure, give a brief account of some of its chapters, and offer a few words of critique.

*

Example 1. Rethinking Schubert, Table of Contents

(click to enlarge)

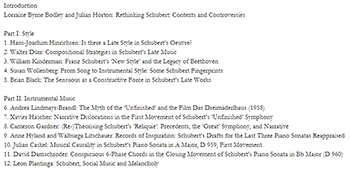

[5] RS has its origin in an international conference that took place at Maynooth University in October 2011. The conference, entitled “Thanatos as Muse? Schubert and Concepts of Late Style,” has proven fecund; its 66 papers have yielded no fewer than four print volumes, one of them a 20-chapter companion volume published by Cambridge University Press.(2) The 23 papers included in RS were selected by Byrne Bodley and Horton with two goals in mind: to “integrate very detailed technical analyses with more general scholarly issues of Schubert reception,” and to “include leading German-language and francophone Schubert research in an English-language volume of essays” (xi).(3) RS’s table of contents is given in Example 1.

[6] Three areas in particular are given special attention: “matters of style, the analysis of harmony and instrumental form, and text setting” (3). “Each of these fields,” the editors write, has “received fresh stimulus in recent years through the development of new hermeneutic and theoretical approaches and the discovery of fresh source materials.” RS seeks primarily “both to affirm and to extend these developments through a thematic exploration of Schubert’s compositional style (in Part I) and [through addressing] issues in tonal strategy and form in Schubert’s instrumental and vocal music (in Parts II and III)” (3).

*

[7] Part I of RS is devoted to the challenging question of whether one can “speak of late style for a composer who died at the age of thirty-one” (4).(4) Its five essays address the question to greater and lesser degrees. But if they are not unified around the tricky aesthetic problem of “late style” per se, these essays nevertheless center around a small but important set of Schubert’s “late works”: the Quartettsatz D. 703; the Piano Trio in E-flat major, D. 929; the last three piano sonatas D. 958, 959, and 960; and the Cello Quintet D. 956.

[8] The common repertoire creates points of contact between the essays in Part I, but there are also points of friction. And here—as always—it is the disagreements, not the consensuses, that kick up the instructive questions. Did Schubert’s music undergo an identifiable style change or compositional “maturity”? Was it in 1818 (Wollenberg), 1820 (Kinderman), 1824 (Hinrichsen), or 1826 (Dürr)? What social, biographical, and physiological factors led to the change? Is the “new style” informed by Schubert’s experience in writing song (Kinderman, Wollenberg)? And to what extent does the shift represent a move away from Schubert’s “old style,” versus a “consolidation of existing positions” (Dürr)?

[9] In Part I, essays by Walther Dürr and Brian Black engage with a novel issue in Schubert scholarship: the extent to which “sonority”—the sensual sounding surface of the music—can be taken as an independent and potentially structural musical parameter.(5) In “Compositional Strategies in Schubert’s Late Music,” Dürr suggests that Schubert cultivated a “special interest” in sonority, and that in the late works, it “becomes significant for the structure of entire movements” (36). In “The Sensuous as a Constructive Force in Schubert’s Late Works,” Black echoes both of Dürr’s theses, assuming not only that Schubert was “acutely sensitive to the purely sensuous quality of sound” (77) but that he “takes the sensuous elements of his style and

[10] Ultimately, neither of these essays succeeds unequivocally in defining the “sensuous in Schubert” or in grounding this definition in analysis. And yet, taken together, they set a high-water mark for Part I because they invite readers to frame concepts they think they know well (harmony, chord configuration, modulation) in new ways—or even as epiphenomena. Indeed, Black’s prismatic notion of the sensuous is strong enough to refract even the light of historical critique: “All of the features attacked by Schubert’s critics are products of his cultivation of the sensuous” (90).

[11] In Part II, devoted to “analytical excursions into style, harmony and form” in the instrumental music (5), three essays with a strong historical component stand out as exemplary. In “The Myth of the ‘Unfinished’ and the Film Das Dreimäderlhaus (1958),” Andrea Lindmayr-Brandl “reveal[s] the circumstances

[12] In “Records of Inspiration,” Anne M. Hyland and Walburga Litschauer compare the extant continuity drafts of Schubert’s final trilogy of piano sonatas with the finished versions of these pieces. Hyland and Litschauer classify Schubert’s revision strategies into four categories (all of which result in added measures): the addition of exact repeats, the addition of octave repeats, the addition of sequences, and the addition of silent measures (181–85).(7) Especially compelling is that the authors use the results of their documentary source study to illuminate the hypermetric, proportional, and aesthetic effects wrought by Schubert’s revisions to the first movement of D. 960 (190–95). The reader may be loath to take, as Hyland and Litschauer do, all of Schubert’s revisions as aesthetic improvements or augmentations of “organic unity.” But we gain enormously from their demonstration of Schubert’s working methods, and their essay may also help to unsettle the myth of Schubert’s “somnambulism.”(8)

[13] Leon Plantinga’s luculent “Schubert, Social Music and Melancholy” marries two competing visions of Schubert—“the guileless composer of lilting songs” and the melancholic, tormented pessimist—with two similarly competing aspects of early-nineteenth-century Vienna: the “comfortable and carefree” Biedermeier and the repressive Metternich regime (237–38). Plantinga’s essay sensitizes the reader to the commingling of these realms in Schubert’s music. Of particular interest is the attention he gives to the characteristic elements of the Viennese soundscape—Ländler, tavern songs, and dance hall music—that permeate even Schubert’s most despairing movements, such as the Andantino of D. 959. For Plantinga, such admixtures are “an impressive and characteristic achievement of Schubert’s late big pieces” (241–42).

[14] The opening pair of essays in Part III give hermeneutic attention to some relatively neglected Schubert songs, but Mark Spitzer and Suzannah Clark have diametrically opposed views on the relevance of neo-Riemannian methods to Schubert analysis. In “Axial Lyric Space in Two Late Songs,” Spitzer argues that “Neo-Riemannian mania [in Schubert scholarship] has distorted as much as it has illuminated,” that it “[picks] out brute chords at the expense of the melodic, rhythmic and formal treatment which surely constitutes the essential fabric of Schubert’s musical language” (253). His analyses of “Im Freien” D. 880 and “Der Winterabend” D. 938 are designed to recuperate some aspects of Schubert’s style—most importantly of Schubert’s melodic constructions—that he sees as having been “lost amidst the furore over his tertial harmony” (272).

[15] Clark counters Spitzer not with a theoretical defense but with a demonstration of the mechanics, analytical power, and limits of neo-Riemannian theory so clear that it could (and will presently) be assigned to undergraduates. Her “Schubert through a Neo-Riemannian Lens” engages with “Schwanengesang” D. 744 from Schenkerian and neo-Riemannian perspectives, showing how each mobilizes a different hermeneutic interpretation. This approach highlights the idea that different analytic technologies mediate the musical object in different ways, causing some of its elements to rise to awareness while allowing others to pass unnoticed through the sieve.(9) In a wonderful touch, Clark marshals her neo-Riemannian reading of “Schwanengesang” as a possible explanation for why the song escaped the criticism of an unsympathetic historical reviewer (275–76, 289).(10)

[16] A trio of mutually implicative essays in the latter half of Part III addresses three songs from Schwanengesang. In “Dissociation and Declamation in Schubert’s Heine Songs,” David Ferris illustrates how “shifts in narrative perspective” in Heine’s “Der Atlas” and “Der Doppelgänger” depict “a process of psychological dissociation”—“a dividing and doubling of the self” (385). On Ferris’s reading, these dissociations are made manifest in the harmonic, voice-leading, and declamatory subtleties of Schubert’s settings.

[17] In “The Messenger of a Faithful Heart,” Richard Giarusso reaffirms the place of Schubert’s final song, “Die Taubenpost,” in Schwanengesang. Despite its tuneful, “pleasing” style (411)—“all sweetness and good humor” (Reed 1997, 200)—“Die Taubenpost” is nevertheless not to be read as an aberration as has been done historically, but as evidence for the “essential lack of unity in Schubert’s late style” (413). Indeed, “the style of late Schubert,” for Giarusso, “is predicated upon radical heterogeneity” (411).

[18] In his essay, Giarusso mentions Sontag’s caution that “one cannot use the life to interpret the work” (1972 , 111). If he had quoted the following sentence—“but one can use the work to interpret the life”—he would have elegantly captured Benjamin Binder’s approach in “Disability, Self-Critique and Failure in Schubert’s ‘Der Doppelgänger.’” Here Binder proposes a reading of “Der Doppelgänger” that is radically rooted in Schubert’s biography. The song is “a self-portrait of the composer in his final years, physically, psychologically and creatively crippled by the effects of

*

[19] As with Schubert’s late songs, the individual essays of RS are radically heterogeneous. Unlike Giarusso’s description of Schubert’s final song vis-à-vis the other songs of Schwanengesang, however, the essays differ not only in style and content (the metaphorical “Die Taubenposts” of the volume appearing cheek by jowl with its Heinelieder), but also in clarity, organization, and general readability.(11) Against this backdrop, the essays that emerge as exemplary are often simply those that are clearly written or organized. David Damschroder’s essay on “6-phase chords” in the finale of D. 960, for instance, distinguishes itself for its succinctness and concinnity, and Byrne Bodley’s essay on “Der Musensohn” may be praised for its lucid account of Goethe’s wanderer trope.(12) Still, many of the suggestive and promising essays in this volume are ultimately vitiated by turgidity or disorganization.

[20] Two further critiques are applicable at the editorial level. First, RS’s tripartite division—style, instrumental music, texted music—suggests a cleanliness of organization that its essays ultimately reject. The essays coalesce far more around the topic of Schubert’s late style, the theme of the conference from which they stem, than around the divisions imposed by the editors. Second, one may reasonably question the appropriateness of RS’s title, for the volume—as a whole, anyway—does not pursue a revisionist agenda. Few of its essays gesture toward “rethinking” aspects of the received image of Schubert, let alone reappraising or endeavoring to supplant the regnant forms of thought.

[21] Here, one must be fair to the editors, who explicitly state that RS has two goals: reevaluation and consolidation.(13) Still, even if the tension that emerges between essays will be productive for future dialogues, and even if RS is at bottom not a thesis-driven volume but a compendium of research, the title accrues an air of the disingenuous, as if it were chosen more for its flashiness than for its aptness. To my mind, these three critiques may be placed under a single umbrella: the volume does not transcend its origins as a set of conference proceedings.

*

[22] Before closing, I wish to identify a deeper, and potentially more problematic, issue in Schubert studies at large: our seeming inability to relinquish a set of inherited discursive habits, even when they are at odds with the state of the field. An acute instance of this sort of rhetorical reflex may be found in RS’s introduction, which begins by proclaiming a new era in Schubert studies, marked by a productive “flowering of theoretical and analytical engagement with his music,” but which then moves on to mention a “habitual critical hostility” that has attached itself to his music.(14)

[23] Yet these two of the editors’ claims cannot both be true (at least not at the same time): that Schubert’s music has been integral “to the burgeoning theoretical and analytical literature on nineteenth-century harmony and form” and “has played an even more significant role in the recent evolution of harmonic theory”—in short, that “Schubert’s importance for the present condition of musical scholarship is hard to overstate” (2)—and that it suffers from a critical neglect. The hostility mentioned by Byrne Bodley and Horton is characteristic of an earlier era of Schubert studies; it is no longer a part of the field.(15)

[24] I mention the point here not because such tropes ring false (although they certainly do). Still less do I wish to allege that they are deliberate red herrings. It is more that the new era in Schubert studies proclaimed by RS—and which RS helps to usher—will be most productive if it is characterized not by an unreflective reliance on the discursive habits of a bygone age, but by a willingness to recognize Schubert’s current, privileged position “at the centre of mainstream music theory” (1).

*

[25] RS’s concluding chapter, written by Graham Johnson, is as much a memoir as it is an homage to Walther Dürr. Writing about some Schubertiana that occupy his bookshelves, Johnson mentions some Dover reprints of the Breitkopf und Härtel Schubert Gesamtausgabe that he acquired in the early 1970s. “Despite some inevitable mistakes and misapprehensions,” he writes of Mandyczewski’s edition, “(this was 1894, remember

[26] With these words, Johnson might equally well be describing RS, a compendium that will continue to be valuable for future scholars even as it bears the indelible marks of its own era—the era in which Schubert came to occupy a privileged position in the theoretical and analytical discourse at large. As with Mandyczewski (and with all texts, ultimately), RS contains some “inevitable mistakes and misapprehensions.” But its most successful essays give a glimpse of the bright future of Schubert studies. To return to the language of my opening, they show us new ways of turning over new leaves.

Jonathan Guez

Scheide Music Center

525 E. University St.

Wooster, OH 44691

jguez@wooster.edu

Works Cited

Burnham, Scott. 2016. “Beethoven, Schubert and the Movement of Phenomena.” In Schubert’s Late Music: History, Theory, Style, ed. Lorraine Byrne Bodley and Julian Horton, 35–51. Cambridge University Press.

Byrne Bodley, Lorraine, and Julian Horton, eds. 2016. Schubert’s Late Music: History, Theory, Style. Cambridge University Press.

Byrne Bodley, Lorraine, and James Sobaskie, eds. 2016. Special issue, Nineteenth-Century Music Review 13 (1).

Clark, Suzannah. 2011a. “On the Imagination of Tone in Schubert’s Liedesend (D473), Trost (D523), and Gretchens Bitte (D564).” In The Oxford Handbook of Neo-Riemannian Theories, ed. Edward Gollin and Alexander Rehding, 294–321. Oxford University Press.

—————. 2011b. Analyzing Schubert. Cambridge University Press.

Drabkin, William, ed. 2014. “Schubert’s String Quintet in C major, D. 956. Papers Read at the Conference ‘Schubert and Concepts of Late Style,’ National University of Ireland, Maynooth 21–23 October 2011.” Special issue, Music Analysis 33 (2).

Guez, Jonathan. 2015. Schubert’s Recapitulation Scripts. PhD diss., Yale University.

Hatten, Robert. 1993. “Schubert the Progressive: The Role of Resonance and Gesture in the Piano Sonata in A, D. 959.” Intégral 7: 38–81.

Pascall, Robert. 1974. “Some Special Uses of Sonata Form in Brahms.” Soundings 4: 58–63.

Reed, John. 1997. The Schubert Song Companion. Mandolin.

Rothstein, William. 2008. “Common-Tone Tonality in Italian Romantic Opera: An Introduction.” Music Theory Online 14.1. http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.08.14.1/mto.08.14.1.rothstein.html

Samarotto, Frank. 2009. “‘Plays of Opposing Motion’: Contra-Structural Melodic Impulses in Voice-leading Analysis.” Music Theory Online 15.2. http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.09.15.2/mto.09.15.2.samarotto.html

Sontag, Susan. 1972. Under the Sign of Saturn. Vintage Books.

Footnotes

1. For a list of developments in Schubert scholarship and a useful bibliography, see Byrne Bodley and Sobaskie 2016, 3–9, and Rethinking Schubert, 1–14.

Return to text

2. See Byrne Bodley and Horton 2016, Byrne Bodley and Sobaskie 2016, and Drabkin 2014.

Return to text

3. RS introduces Anglophone readers to the work of Hans-Joachim Hinrichsen, Xavier Hascher, William Kinderman, and Walther Dürr (to whom the volume is dedicated). It also includes essays by William Kinderman and Lorraine Byrne Bodley that were previously published in German. American readers will find these chapters (as well as those by British authors) valuable, not only as windows onto the European perspective, but also for their bibliographies, which are treasure troves of European sources.

Return to text

4. Summaries of all of RS’s essays are given on pp. 3–10.

Return to text

5. The image is of Schubert as a sort of “calligraphic” composer who gave unprecedented attention to the materiality of his medium. Important precedents here are Hatten (1993) and Burnham (2016, 41), who writes, “In [the opening of the G-Major Quartet, D. 887] we hear

Return to text

6. One wonders, in this regard, how Dürr’s and Black’s notion of “sonority” interacts with what Pierluigi Petrobelli has called “sonorità”; Rothstein (2008) and Clark (2011a; 2011b, 99ff.; and RS, 290) would provide compelling links between the two ideas.

Return to text

7. The only example they give of a finished version that is shorter than the continuity draft is the development section of the first movement of D. 959, which is one bar shorter than the draft (178–80). This, however, is an “isolated instance”; “Tables 9.1 and 9.2 [demonstrate] more or less unequivocally that Schubert’s more usual revision process involved the expansion

Return to text

8. Still, will the discovery that Schubert unfailingly expanded his sonata forms result in higher valuations of his music?

Return to text

9. Her essay ought also to remind Spitzer that analytic techniques are not good or bad in themselves, but are always deployed by an analyst. In Clark’s hands, neo-Riemannian theory is made to address melody, and certainly there have been Meyerian analyses of “axial melodies” that overlook important elements of the compositional language.

Return to text

10. Clark’s essay also responds to Spitzer’s in a deeper way. Spitzer asks: “Why

Return to text

11. RS’s clarity is further compromised by an abundance of errors. Some of these are typographical and mildly peeving: e.g., the mislabeled Example 8.3 (156), the repeated “textural”/“textual” toggle in Caskel’s essay (209, 212, 213), and the omission of the double-flat symbol in Gardner’s essay (158). Others make analyses slightly difficult to follow: e.g., Clark’s “R” for “RP” (287) and “LP” for “LR” (284). Larger errors take away significantly from the experience of reading. Stein’s essay, for instance, features misspellings (of words, song titles, and authors’ names), misattributions of sources, examples whose numbers are misidentified in the text, music examples that are not uniformly engraved, music examples that do not have the features mentioned in the text, a sentence that ends with two periods instead of one, a subheading that appears in the main text, and an incorrect title that appears on the recto side of each page.

Return to text

12. Damschroder reads the finale as a sonata rondo whose recapitulation begins at m. 312 and “offers no surprises” (234). Is it possible, though, that this is not the beginning of the recapitulatory rotation, but rather its resumption, after a 56-measure interpolation? This reading, advanced by Pascall (1974), has the additional benefit of situating the movement among Schubert’s other “expanded bi-rotational” finales, such as those of D. 956 and 804 (cf. Guez 2015, 292–313).

Return to text

13. Revisionism is given pride of place in the volume’s title and first sentence—“The time is propitious for a re-evaluation of Schubert scholarship” (1). But the editors wish also “to consolidate the gains” of recent work in Schubert studies (2). On the one hand, then, RS seeks to “assemble a portrait of the artist that reflects the different ways in which Schubert has been misunderstood over the past two hundred years, and provide a timely reassessment of Schubert’s compositional legacy” (4). On the other, it aims to offer a “conspectus of current scholarship” (10). These two enterprises mirror the conflicting positions on Schubert’s late style laid out in Dürr’s essay (29).

Return to text

14. “Most striking” about RS, Byrne Bodley and Horton write, is “the depth of thought that attaches to the instrumental works,” whose reception history “has proved uncongenial to musical analysis” (10).

Return to text

15. Another trope that continues to permeate the Schubert discourse but that has long since lost its truth value: “it is no longer acceptable to dismiss Schubert’s instrumental forms as flawed lyric alternatives to Beethoven” (10).

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2017 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Samuel Reenan, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

7146