Review of John Franceschina, Music Theory through Musical Theatre (Oxford University Press, 2015)

Brian D. Hoffman

KEYWORDS: pedagogy, textbooks, musical theatre

Copyright © 2017 Society for Music Theory

[1] In today’s saturated market, creating a music theory textbook with a truly novel perspective is both rare and difficult. For this reason, John Franceschina’s Music Theory through Musical Theatre (MTMT) is a true achievement: it is the first music theory textbook aimed at college-level musical theatre students and suitable for a four-semester sequence.(1) Furthermore, MTMT’s singular focus on the application of music theory to a life on stage makes this an unprecedented tool for its target students and instructors. Franceschina establishes the book’s raison d’être in his introduction for teachers: “Not simply a traditional music theory text using musical theatre examples, this book tackles the theoretical foundations of musical theatre and musical theatre literature with an emphasis on what students will need to know in preparation for a professional career” (3). While MTMT achieves its overall goals, it is pedagogically hindered by problematic definitions and a lack of creative exercises. After introducing the book’s features, I will highlight three issues: Franceschina’s commitment to linking music-theoretical concepts with stage drama, differences between MTMT and traditional textbooks in terms of topics covered, and problems with the book’s treatment of core concepts.(2)

[2] Franceschina organizes the book into three units that represent a song’s journey from composition to performance: “Lead Sheet,” covering scales, rhythm, and intervals; “Arrangement,” dealing with chord spelling, functional harmony, and song form; and “Performance,” relating analyses of complete songs to performance. Each chapter includes exercises that can be completed in or out of class, and each unit concludes with a series of cumulative tests that can be used for review. A coordinated website offers MIDI playback of most musical examples.

[3] He supplements the first two units with sporadic keyboard and sight-singing exercises, but these are neither frequent enough nor sufficiently tiered to be a useful feature of the book. For example, Chapter 2 introduces the concept of movable-do solfège syllables; one of the first sight-singing exercises in that same chapter contains a tritone leap and consecutive leaps of a perfect fourth all within the first measure. Chapter 4 presents all chromatic solfège syllables at once and immediately assigns melodies that incorporate chromatic passing tones and outlines of secondary dominant harmonies. Typically, such melodies do not appear until the end of the second semester of a college sight-singing course; in MTMT, they appear just two chapters after students sing “do re mi” for the first time. The banks of sight-singing melodies disappear altogether after Chapter 5.(3) Thus, MTMT does not offer enough material for an integrated course in music theory and sight singing. Furthermore, it does not contain any other ear-training exercises.

[4] In his introduction, Franceschina is somewhat vague about his intentions for these portions of the book: “The sight-singing components in MTMT are designed to correlate with any ear-training requirements in the musical theatre curriculum and to assist students in thinking critically and analytically about the notes on a page and associating them with specific points of musical theory” (5). If he simply intends the exercises in MTMT as supplements to an independent sight-singing text, then the banks of sight-singing melodies early in the text are unnecessary. The inclusion of these melody banks places MTMT awkwardly between a fully integrated text and a stand-alone text on written music theory.

Music Theory and the Drama of a Song

[5] The highlight of MTMT is its final unit, which achieves Franceschina’s stated goal of emphasizing professionally relevant knowledge. Each chapter in the unit includes detailed analyses that synthesize music-theoretical concepts with the dramatic context of a song within a musical. In addition, he provides historical background for each show discussed. The seven composers highlighted in this unit appear chronologically: George Gershwin and Richard Rodgers represent the 1930s–1940s, Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim the 1950s–1970s, and Andrew Lloyd Webber, William Finn, and Jason Robert Brown the period since 1980.(4) In these three chapters, Franceschina’s considerable experience as a music director and author shines through. Focusing on form, motive, and key, he shows students how to discern dramatic cues in the music itself. Readers are treated to clear and insightful passages such as the following: “In ‘What a Waste’ the syncopated figure evokes the restless energy of New York City in much the same way as the ever-changing harmonic figure in the accompaniment to Sondheim’s ‘Another Hundred People’ paints an aural portrait of the fast-paced urban environment” (378).

[6] In addition to the excellent prose, the assignments in this unit facilitate real-life integration of the concepts from the first two units with the daily activities of a musical theatre performer. Franceschina achieves this in part by asking students to consider the same six elements of a song in every assignment: creating a mood or tone, identifying character, playing subtext, establishing locale, creating emphasis, and establishing the rhythm of the dramatic event.(5) This repetition transforms mere textbook assignments into a protocol for approaching any song the student may encounter. He encourages application by inviting students to draw from their own repertoire for analytical examples, but limits this suggestion to songs written before 1950. Presumably such songs pose less risk of having unidentifiable forms or harmonies.

[7] Although the third unit’s essays offer a welcome change from the traditional textbook format of the first two units, they do not consistently use the terminology introduced earlier. For example, Franceschina opts not to label an 11th chord in Jason Robert Brown’s “It’s Hard to Speak My Heart” despite an earlier chapter on extended harmonies. Instead, he describes its “raised fourth . . . with an added major seventh” (415). By missing an opportunity to model proper terminology, he may cause students to question the value of having learned the terms in the first place.

Choice of Topics

[8] Franceschina has jettisoned music-theory topics that he considers superfluous to a career in musical theatre, while retaining essential ones and adding specialized content. Specialized topics include sonorities such as major and minor sixth chords (e.g., C6 and Dm6), “add2” and “sus4” chords, and alternative “backdoor” cadences such

[9] Many sections conclude with the names of around ten musical theatre songs that illustrate a topic. Augmenting the ample number of piano-vocal excerpts in the text, these lists of song titles provide more than one hundred extra examples without raising the price of the textbook due to added copyright fees. While it may be idealistic to imagine a student looking up the score of Richard Rodgers’s No Strings simply to find an example of a passing tone, the lists provide instructors with additional material for in-class examples and homework. This is an especially valuable resource for an instructor without an encyclopedic knowledge of the musical theatre repertoire.

[10] Franceschina further emphasizes these specialized topics by eschewing any material not deemed immediately relevant to life on the stage, such as figured bass, classical form, and four-part voice leading. Yet in doing so, he has underestimated the pedagogical value of creative “doing” as opposed to mere mechanical spelling and labeling. This becomes particularly evident in the chapters on harmonic function, form, and counterpoint.

[11] For example, in Chapters 7 and 8, he introduces the rules of all five species of counterpoint at a level of detail similar to that in traditional textbooks. However, he never asks the student to write a single counterpoint exercise, complete an error-detection task, or engage analytically with the principles of counterpoint. Even his own analyses point out only remnants of species counterpoint, stopping short of demonstrating its utility to a performer. These chapters might leave instructors wondering whether their students should learn the detailed rules at all—and, if so, how they should practice the species or implement them in preparation for a professional career. In contrast, other counterpoint texts generally employ compositional exercises and error detection as the primary means of reinforcing concepts.(6)

[12] One could rationalize that composing counterpoint or voice leading lies outside the daily activities of a musical theatre performer and is therefore superfluous given the author’s goals. However, these practical activities are pedagogically crucial to acquiring the level of comprehension that Franceschina requires of students in the final unit of his book. As textbook authors Jane Piper Clendinning and Elizabeth West Marvin write in the preface to their workbook, “The study of music theory is not a spectator sport. To learn musical elements and how to analyze them requires action” (2016, vii).(7)

Opaque Wording and Misleading Definitions

[13] On top of MTMT’s paucity of opportunities for creative practice, students may find its wording misleading or opaque. For example, Franceschina offers this guideline for determining interval quality: “If the upper note [of an interval] would naturally appear in the scale of which the lower note is the tonic, then the interval is either perfect or major” (79). He describes the perfect unison as follows: “A repetition of pitches involving no half steps, the perfect prime interval, most commonly known for its ubiquitous use in Antonio Carlos Jobim’s ‘One-Note Samba,’ has long been a staple of music theatre literature because of its consonant and emphatic reiteration of a single tone” (76). In both cases, Franceschina’s syntax requires that the student translate rather than simply absorb the information.

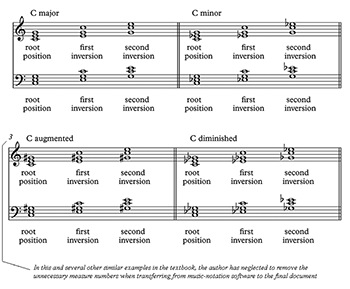

[14] MTMT sometimes compounds difficult wording with misleading or inaccurate explanations. The instructions regarding chord inversion serve as a representative example: “When presented with an inversion of a triad in the accompaniment of a musical theatre work, simply reposition the tones of the inversion to create a triad in thirds (the root position): when the third is on the bottom (first inversion), drop the top note (the root) down an octave; when the fifth is on the bottom (second inversion), raise the bottom note an octave” (106). Franceschina never informs the student that this is a procedure to identify the root and quality of a chord, even though that is the goal. Furthermore, for a beginning student, phrases like “reposition the tones of the inversion” might take repeated readings to understand. In contrast, Steven Laitz’s explanation of the same concept is clear: “A triad is in root position if the root is the lowest-sounding pitch. . . . If the third or the fifth of a triad appears in the bass, the triad is in first inversion or second inversion, respectively. It doesn’t matter how the pitches above the bass are distributed; the pitch in the bass determines whether the chord is in root position or an inversion” (2015, 64).

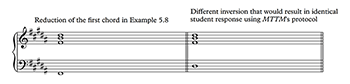

Example 1. Second-inversion triad from MTMT, Example 5.8 and my revoicing of the chord

(click to enlarge)

Example 2. Example 5.7 from MTMT

(click to enlarge)

[15] Franceschina’s procedure is not just hard to unpack, however; for textures other than three-note voicings in close position, it is misleading. Example 1a reproduces an exercise in MTMT that asks students to identify the root and quality of a second-inversion B-major triad in a keyboard texture. When a student attempts to apply the textbook’s methodology, one of two mistakes could happen. In attempting to follow Franceschina’s instructions to raise the bottom note an octave when it is the fifth, the student may raise the

[16] Some explanations in this textbook are overgeneralizations, such as the description of a major triad: “From a dramatic perspective, major triads are positive and sturdy. They create musical declarative sentences” (103). Others are simply not correct. In the section on modes, Franceschina misidentifies the mode of the melody in David Yazbek’s “Big Black Man” as Dorian. The tonal center of the song is G and the underlying harmony—which not shown in the textbook—is G7. Thus, it is an example of the Mixolydian mode. Similarly, he lists Richard Rodgers’s “Climb Ev’ry Mountain” (misspelled in the textbook) as an example of the Lydian mode despite the tonal context of

[17] Experienced musicians certainly know what Franceschina means. However, the unclear passages would be likely to perpetuate rather than resolve the very common mistakes and misunderstandings of an undergraduate student. The book would be stronger with simplified definitions, accurate depictions of concepts like mode, and concrete musical examples in place of overgeneralized descriptions.

Conclusion

[18] Music Theory through Musical Theatre is a much-needed addition to existing pedagogical resources, given the increased prevalence of collegiate musical theatre programs with dedicated music theory courses. This book is at its best when it reflects Franceschina’s considerable experience as a music director and author. Beginning students may struggle to fully understand music-theoretical topics due to difficult wording and some marginally correct statements, but an experienced educator could mitigate some of these pedagogical shortcomings. Overall, MTMT provides students with a blueprint for becoming informed interpreters and performers of the musical theatre literature.

Brian D. Hoffman

Cincinnati, OH

hoffmaba@gmail.com

Works Cited

Bell, John, and Steven R. Chicurel. 2008. Music Theory for Musical Theatre. Scarecrow Press.

Clendinning, Jane Piper, and Elizabeth West Marvin. 2016. The Musician’s Guide to Theory and Analysis, 3rd ed. Norton.

Colletti, Carla R. 2013. “The Silent Professor: Enhancing Student Engagement through the Conceptual Workshop.” Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy 1. http://flipcamp.org/engagingstudents/colletti.html.

Hoag, Melissa. 2013. “Hearing ‘What Might Have Been’: Using Recomposition to Foster Music Appreciation in the Theory Classroom.” Journal of Music Theory Pedagogy 27: 47–70.

Kostka, Stefan, Dorothy Payne, and Byron Almén. 2012. Tonal Harmony with an Introduction to Twentieth-Century Music, 7th ed. McGraw-Hill Education.

Laitz, Steven G. 2015. The Complete Musician: An Integrated Approach to Tonal Theory, Analysis, and Listening, 4th ed. Oxford University Press.

Roig-Francoli, Miguel. 2011. Harmony in Context, 2nd ed. McGraw-Hill.

Schubert, Peter. 2008. Modal Counterpoint, Renaissance Style, 2nd ed. Oxford University Press.

—————. 2013. “My Undergraduate Skills-Intensive Counterpoint Learning Environment (MUSICLE).” Engaging Students: Essays in Music Pedagogy 1. http://flipcamp.org/engagingstudents/schubert.html.

Stempel, Larry. 2010. Showtime: A History of the Broadway Musical Theater. Norton.

Footnotes

1. Bell and Chicurel 2008 is aimed at collegiate musical theatre students, but serves as a supplement to a traditional textbook. It is not suitable (or intended) for a four-semester sequence.

Return to text

2. To determine a benchmark for a “traditional textbook,” I have consulted Roig-Francoli 2011; Kostka, Payne, and Almén 2012; Clendinning and Marvin 2016; and Laitz 2015. While this is not an exhaustive list, it is representative of the commonly used literature.

Return to text

3. Chapters 7 and 8 contain only species counterpoint exercises, which are not idiomatic to musical theatre style. From Chapter 9 forward, Franceschina invites students to sight-sing whichever musical examples appear in the course of the chapter and occasionally asks them to perform the accompaniment on piano.

Return to text

4. Franceschina acknowledges that several notable composers do not appear in the final unit of MTMT. He explains that their songs “exhibited musical and dramatic issues similar to those pieces [already] examined in the book” (400). Each composer included holds an integral place in the musical theatre canon according to both performance practice and recent histories such as Stempel 2010.

Return to text

5. The last of these elements appears in many subtle variations throughout the unit: “establishing the dramatic rhythm of the musical” (375), “establishing the rhythm of the musical or dramatic event” (391), and “establishing the rhythm of the dramatic event” (398, 404, 417). It is unclear whether the variations convey different meanings or instead result from editorial oversight. The exact meaning of this phrase can perhaps be inferred from the analyses in the chapter, but is never explicitly stated.

Return to text

6. See, for example, Roig-Francoli 2011 or Schubert 2008. Peter Schubert (2008) has since demonstrated how to teach modal counterpoint through vocal improvisation, a skill that would be particularly relevant to Franceschina’s intended readers.

Return to text

7. In addition to the textbooks listed in note 2, articles such as Colletti 2013 and Hoag 2013 echo the pedagogical importance of creative music-writing exercises.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2017 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason, Managing Editor

Number of visits:

7333