Review of Jeffrey Swinkin, Performative Analysis: Reimagining Music Theory for Performance (University of Rochester Press, 2016)

Daphne Leong

KEYWORDS: performance, analysis, Schenker, theory

Copyright © 2017 Society for Music Theory

[1] Despite the recent surge of scholarly work on musical performance, monographs devoted to the relationship between analysis and performance are still scarce.(1) Stein 1962, Cone 1968, and Berry 1989 (along with Rink’s 1995 edited collection) provide precedents. Among more recent literature, Klorman 2016 interprets musical structure in Mozart’s chamber music as performative social interplay, and De Souza 2017 reads structure within an interplay of instrument, body, and cognition. And Cook 2013 addresses relationships of analysis and performance in the context of reconceiving “music as performance.” But direct book-length treatment of the relationship between analysis and performance remains rare.

[2] How does one construe rigorous analysis—Schenkerian analysis in particular—so that it becomes useful for performance? Jeffrey Swinkin answers this question by “reimagining music theory for performance.” With an introduction, two theoretical chapters, and three analytical ones, he depicts Performative Analysis—analysis that unearths structural ambiguities and delineates physical and emotional metaphors—ambiguities and metaphors to which a performer responds.

[3] The book takes on a number of knotty philosophical issues: work ontology, the function of musical analysis, the role of the performer, and the construction of musical meaning.(2) Swinkin views the musical work as based in the score, elucidated by analysis, and completed by the performer. The score—the object of analysis—becomes, through analysis, “a set of structural and emotional potentials that the performer grapples with and fulfills.” That is, analysis “consolidates the score’s performative implications: if a material trace allows for multiple potential relationships, particular music-analytical models circumscribe this set, indicating what in particular the performer-listener is to imagine about that trace” (37). Analysis is therefore a “crucial interlocutor between score and performer or perceiver” (38).

[4] Furthermore, analysis implicitly recommends “how to hear, and by extension, perform a piece” (16); it neither describes actual hearing nor prescribes hearing or performance, but suggests hearing and playing “as if.” In this way the interpreter—both analyst and performer—“creates or constructs meaning from notational potentials paired with an analytical apparatus” (18). Such meaning is emergent and multiple: a given musical event can give rise to divergent analytical readings with different performance implications, each realizable in many ways (7).

[5] But music is presentational rather than discursive: it presents or embodies internal experience. Hence performance does not communicate analytical assertions, but may embody them in such a way that the listener hears the music as meaningful and coherent. The listener then understands the music implicitly, without explicitly understanding its structure (26).

[6] Swinkin’s primary analytic methodology is Schenkerian analysis. He uses it to examine a solo piano piece, a string quartet movement, and a song: Chopin’s Nocturne in C minor, op. 48, no. 1; the first movement of Beethoven’s String Quartet in C minor, op. 18, no. 4; and “Du Ring an meinem Finger” from Schumann’s Frauenliebe und -leben. The first analysis relies most heavily upon Schenkerian methodology; the second examines aspects of form, motive, and rhythm as well as tonal structure and voice leading; and the third reads against its Schenkerian interpretation to “resist” the meaning of Schumann’s “Ring.”

[7] Swinkin sets Schenkerian theory against a backdrop of Goethean organicism, Kantian transcendental apperception, and Freudian dream theory—understanding it as organic growth from background to foreground, as a unifying consciousness (the Ursatz) binding tones in time, and as hidden deep structure illuminated by inspired analysis. His concern is with how the unity created by the background manifests in the foreground—not, in performance, with the elements of the background or middleground per se, but with the ways in which they “imbue the foreground with particular dynamic qualities” (16). These dynamic qualities evoke bodily schemata and, through cross-domain mapping, the expressive connotations of such schemata; analytical observations thus function as physical-affective metaphors.(3) One such physical-affective metaphor is “tension”; another, “search for closure and the many obstacles and digressions encountered along the way” (68–71, 94). Imagining such metaphors (and more specific ones), an interpreter weaves an overarching narrative that can be embodied in performance (72).

[8] This methodology is demonstrated in Swinkin’s analysis of Chopin’s nocturne. Swinkin provides a Schenkerian reading and interprets it (together with features of the musical surface) metaphorically. The analysis is illuminating and the interpretation suggestive. They paint a portrait of a weakly, melancholic, and quietly desperate person yearning for stability in the midst of crisis. In the opening A section, the absence of linear progressions suggests weakness and hopelessness while the presence of linear progressions represents clarity and groundedness. In the B section, the awkwardness of the widely spread rolled chords in the left hand hints at tension within a generally reassuring and perhaps transcendent scene.(4)

[9] Swinkin accompanies his analytic interpretation with detailed performance suggestions. For example, he suggests “slightly unstable timing” to convey the irresolute nature of the opening phrase (82). But he also states that “the more overtly hermeneutic and experiential the analysis, the more naturally it will affect the performer, in ways that cannot and should not be precisely prescribed” (75). And he emphasizes that “although a broad correlation exists between Schenkerian analysis and performance in that both thrive on physical and expressive qualities, no exact, predictable, or measurable correlation does. In this lies an inexhaustible source of interpretive richness that we would not want, despite its messiness, to wish away” (95). Indeed, I frequently found myself disagreeing with particular performance suggestions (e.g., slowing down to indicate structural expansion, accelerating to accompany rhythmic acceleration), although not with the overall thrust of Swinkin’s approach.

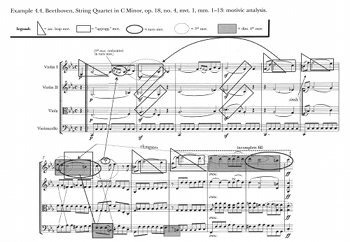

Example 1. Swinkin’s Example 4.4

(click to enlarge)

[10] For the first movement of Beethoven’s String Quartet op. 18, no. 4, Swinkin “coaches” an imaginary student string quartet, proceeding through the movement in sections. The exploration is thought-provoking and the comparisons with passages from Beethoven’s piano sonatas, concertos, symphonies, and other string quartets informative. Swinkin interprets formal, motivic, rhythmic, and tonal details, and follows each analytical point with hypothetical performance experiments. For instance (see Swinkin’s Example 4.4, reproduced in Example 1), Swinkin and the imagined students discuss the degree to which the continuation (mm. 5–13) of the movement’s opening sentence is novel with regard to the presentation. Since it contains both new and continuing elements, Swinkin has the students experiment both with highlighting the novelty of m. 5 through timing and color, and with emphasizing its connections to earlier material by accentuating its “sigh” figures. The students also discuss the multilayered expansion found in the continuation, and try expressing this expansion with a slight allargando.

[11] In this way, the chapter’s “coaching” format facilitates performance exploration of Swinkin’s analytical observations. It also provides opportunity to address real-life performing concerns: the practicality of such a time-consuming interpretive process, the concrete meaning of “all this esoteric explanation,” the distinction between “audacious” and “triumphant” in a particular interpretation. Swinkin is sensitive to the problem of overthinking performance: “If you are listening to what we talked about, you will respond in some meaningful way.

[12] Swinkin, with vocalist Jennifer Goltz, presents a different kind of perspective on Schumann’s “Du Ring an meinem Finger.” In two different readings, Swinkin and Goltz critique the song performatively, “resisting” its potentially “misogynistic” and “oppressive” implications. They interpret (1) features of the musical foreground (contrary motion, motivic inversion, a descending chromatic line, a physically awkward trichord, etc.) and (2) aspects of melody and harmony (that subvert the dominance of deeper Schenkerian levels) as clues to the female protagonist’s empowerment—her protest against the entrapment symbolized by “the ring on her finger.”

[13] Swinkin extrapolates from gendered oppression to other potential arenas of music-interpretive oppression. Music theory, especially “hierarchical hegemony,” applied in a dogmatic manner can act oppressively; “the transcendent work” that demands the “subservience” of the performer can do the same. In response, “the performer maintains his presence simply by not losing his interpretive voice, by not allowing it to be silenced by the work and the score and the institutions that secure their authority” (218). S/he can “assert his or her presence

[14] In light of these statements, I find two aspects of Swinkin and Goltz’s video performances ironic. (Their three performances—a pre-analysis baseline, and the two readings discussed in prose by Swinkin—are found at http://jswinkin.com/publications/performative-analysis-reimagining-music-theory-for-performance/.) The analysis is largely Swinkin’s, with Goltz responding to it and suggesting modifications.(5) On video, Swinkin, the analyst and pianist, is invisible; only Goltz, the singer, is shown.(6) Thus the “performer” Goltz embodies the analyst’s vision, while the “analyst” Swinkin remains hidden, his performing body absent.(7) The appearance of both of these aspects—performer Goltz ceding interpretive primacy to analyst Swinkin, and the invisibility of analytical authority and of performer Swinkin—ironically plays into the essentialism on which Swinkin’s “Ring” analysis draws so heavily.

[15] I present this observation as comment rather than critique; Swinkin’s invisibility seems an inadvertent result of the desire to highlight Goltz’s facial expressions. I also do not quibble with the collaborative relationship per se, as cooperation is one of the most basic tenets in chamber performance and it is only collegial for a performer to help present (and develop) a colleague’s interpretation. But the video, however unintentionally, does communicate a message—a clear “subtext,” to use Swinkin’s term—before any note is sounded.

[16] Two practical comments: first, Swinkin writes for theorists, musicologists, performers, and scholars in related disciplines, but he states, “those who are not professional music analysts will probably want to skip over the rigorous analytical parts, especially chapters 3 and 4” (17–18). These chapters, on Chopin’s nocturne and Beethoven’s string quartet, form the analytical core of the book—the chapters in which Swinkin’s theory of performative analysis finds its deepest working out. I believe that performers would find them worthwhile.(8) Second, the score examples (Example 3.1, Example 5.3, and various passages in chapter 4) are often too small to be played from comfortably. Readers who wish to try out Swinkin’s suggestions may want to have regular-format scores of the Chopin, Beethoven, and Schumann pieces at hand.

[17] Swinkin has performed an admirable act of translation in “reimagining” analytic methodology “for performance.” The endeavor needs to be understood within the purview that Swinkin has set out—“theory for performance”—else it risks being criticized for what it is not: a performance- or performer-centered approach. The analysis is chronologically prior and something to which the performer responds, even as it incorporates performative input and is itself performative in its metaphorical, bodily, affective mode.

[18] In Performative Analysis Jeffrey Swinkin presents an original theory of how analysis—Schenkerian analysis and analysis of tonal music in particular—can be conceived for performance. By framing analysis as indicative of interpretive ambiguities and problems, metaphorical of physical states and associated emotional ones, and suggestive of ways to hear and perform “as if,” he demonstrates how analysis can be “performative” in ways akin to actual performance—and perhaps, even more, to the process of developing a performance through coaching, rehearsal, and practice. Any performer will be familiar with Swinkin’s meta-analytic process of locating problems, internalizing and embodying details and narrative trajectories, and suggesting particular meanings to oneself and to one’s audience. Swinkin’s methodology is indeed performative in a meaningful and practical sense. His “reimagining of music theory for performance” makes a courageous contribution to the field of analysis and performance.

Daphne Leong

College of Music, 301 UCB

University of Colorado Boulder

Boulder, Colorado 80309

daphne.leong@colorado.edu

Works Cited

Berry, Wallace. 1989. Musical Structure and Performance. Yale University Press.

Cone, Edward T. 1968. Musical Form and Musical Performance. Norton.

Cook, Nicholas. 2013. Beyond the Score: Music as Performance. Oxford University Press.

De Souza, Jonathan. 2017. Music at Hand: Instruments, Bodies, and Cognition. Oxford University Press.

Johnson, Mark. 1987. The Body in the Mind: The Bodily Basis of Meaning, Imagination, and Reason. University of Chicago Press.

Klorman, Edward. 2016. Mozart’s Music of Friends: Social Interplay in the Chamber Works. Cambridge University Press.

Rink, John, ed. 1995. The Practice of Performance. Cambridge University Press.

Stein, Erwin. 1962. Form and Performance. Faber and Faber.

Swinkin, Jeffrey. 2015. Teaching Performance: A Philosophy of Piano Pedagogy. Springer.

Zbikowski, Lawrence. 2002. Conceptualizing Music: Cognitive Structure, Theory, and Analysis. Oxford University Press.

Footnotes

1. By analysis I mean analysis that takes as its object the score and what it represents, in distinction to empirical analysis of sound or movement, analysis of performance-related processes such as rehearsal or memorization, analysis of cognition, and so on.

Return to text

2. Swinkin’s Teaching Performance: A Philosophy of Piano Pedagogy (2015) treats many of these issues as well. See the chapters on “Musical Autonomy and Musical Meaning” and “The Performer’s Role” for a clear and succinct presentation of his position and its historical context.

Return to text

3. Swinkin (233n75) cites Zbikowski 2002, and mentions George Lakoff and Mark Johnson only secondarily, as influencing Zbikowski. Swinkin’s mappings among Schenkerian constructs, bodily schemata, and emotive connotations might be clarified by drawing more directly on the concept of image schemata, as presented by Johnson 1987.

Return to text

4. I wondered whether these widely spread rolled chords, especially in tandem with the section’s dotted rhythms, might also tinge consolation with heroism or majesty and thus signal growing strength.

Return to text

5. Swinkin writes, “My working method was to analyze the music, construe the results metaphorically, as symbolic of emotional states, then concretize those states in the form of an inner monologue. I presented this to Goltz, who developed her interpretation in response to it. In some cases she suggested modifications to my subtextual thoughts” (181).

Return to text

6. This seems strange since Lieder are generally considered partnerships between vocalist and pianist.

Return to text

7. In double irony, Goltz also holds a PhD in music theory.

Return to text

8. I am judging hypothetically by the doctoral performance students in my analysis-and-performance seminar.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2017 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Samuel Reenan, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

6355