Analyzing Collaborative Flow in Rap Music *

Robert Komaniecki

KEYWORDS: Rap, hip-hop, rhythm, unity, popular music

ABSTRACT: This article is a study of the ways in which collaboration is signaled in the delivery of rap lyrics. I begin by describing the importance and prevalence of unified flow in music released by rap groups during the genre’s formative period in the 1980s and early 1990s. I follow this with a discussion of the continued importance of unified flow in tracks released by solo artists featuring guest rappers—a practice that has increased in frequency since rap’s inception, while rap groups have become less widespread. To illustrate this point, I analyze several songs that feature guest rappers, each exhibiting a level of flow cohesion that is exceptionally marked and uncommon when compared to most lead/guest rapper relationships. I conclude with some possible reasons for collaborative flow in rap music, as well as a discussion of unity as a theoretical concept. An understanding of the importance of unified flow in shared rap tracks enhances our understanding of the nature of collaboration and musical identity in rap music—a vital endeavor as music theorists strive to become increasingly conversant in the musical idioms and styles of hip-hop.

Copyright © 2017 Society for Music Theory

Introduction

Examples 1a–1d

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Figure 1. (Weingarten 2016)

(click to enlarge)

Example 2. A transcribed excerpt of Busta Rhymes’s performance in “#TWERKIT” (2013)

(click to enlarge, listen, and see the rest)

Example 3. A transcribed excerpt of Nicki Minaj’s guest verse in Busta Rhymes’s track “#TWERKIT”

(click to enlarge and listen)

Figure 2. Data was compiled using numerous webpages on Billboard.com depending on the year.

(click to enlarge)

[0.1] Since rap music’s beginnings in New York in the late 1970s, the concepts of group membership and collaboration have been inextricably attached to the genre. In hip-hop’s early years, collaboration was exemplified in a variety of different ways, ranging from rap “posses” engaging in freestyle rap competitions to organized rap groups writing, recording, and performing music as a team. Many of hip-hop’s most famous rap groups were formed by groups of friends during their teenage years; notable examples include De La Soul, Outkast, and The Lox. Allegiances to a specific city (or group of rappers within a city) were a crucial component of early “battle” rapping, in which rappers would compete against one another in displays of virtuosity and showmanship, for peer and audience approval. Often, rappers explicitly acknowledge a group that they feel allegiance to in their lyrics. Examples 1a–1d show a sampling of rap lyric excerpts in which rappers acknowledge their associations with groups based on various criteria, such as geographic location (Example 1a), membership of a musical group or collective (Example 1b), real or metaphorical gang allegiance (Example 1c), and a generalized entourage or posse (Example 1d). Each of these examples show a rapper’s connection to various subsets of what Justin Williams refers to as the “imagined community” of hip-hop—a complex and self-referential community “maintained through print and electronic media, solidifying traditions, histories, identities, and cultural objects that contribute to its continuity” (Williams 2013, 11).(1)

[0.2] Group cohesion and collaboration in hip-hop stretch beyond lyrical posturing. In the same way that pop/rock groups or bands often start or bolster the careers of solo artists,(2) rap groups and collectives are an integral part of a solo artist’s success in the genre. Figure 1 shows the three members of the rap group Run-D.M.C. dressed in similar attire—an aesthetic confirmation of their shared membership in the group, and an obvious display of cohesion similar to those seen in numerous rock and pop acts. Collaboration, unity, and group membership are such vital components of rap music that their influence can be perceived not only in lyrical content, fashion, etc., but also in the rhythmic, metric, and structural fabric of rappers’ cooperative performances. For the purposes of this article, I will focus only on structural aspects of flow (defined in [1.1] below), rather than also engaging with the semantics of lyrics.(3)

[0.3] As an introduction to my discussion of the significance and prevalence of unified flow in rap music, see Examples 2 and 3, transcriptions of rappers Busta Rhymes and Nicki Minaj’s performances on the Busta Rhymes’ track “#TWERKIT.” I will explain these separate verses, and some notational nuances, in detail below.(4) However, even a cursory glance at the two transcriptions reveals a remarkable level of similarity between the two verses. Busta Rhymes is considered the lead rapper on this track, while Nicki Minaj is featured as a guest artist.(5) Beyond this connection, the pair is ostensibly unaffiliated—yet specific features of their deliveries betray a close degree of collaboration. Both rappers tend to begin and end measures with the same rhythmic figure, given as Motive A in Example 2b: two sixteenth notes and an eighth note, beginning on the beat. Additionally, both rappers noticeably drop the general pitch of their delivery after exactly four measures of rapping. Perhaps most notably, both rappers’ performances utilize an approximation of Caribbean patois, a technique absent from most of their other recordings.(6) It seems obvious that these technical commonalities are the result of close collusion between the two artists.

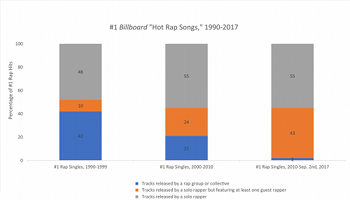

[0.4] The degree of similarity between the two performances transcribed in Examples 2 and 3 is indicative of a longstanding tradition of collaboration in hip-hop music. The importance of affiliation is both explicit and implicit in the history of rap.(7) During the genre’s formative years (the 1980s and early 90s), rap groups were extremely common. Groups such as Run-D.M.C., The Roots, the Beastie Boys, and A Tribe Called Quest dominated much of this early landscape. In recent years, rap groups have declined in prominence, but collaboration between solo rappers in hip-hop is still very frequent. Kyle Adams (2016, [8.4]) notes that “contemporary rap artists nearly always record as soloists, even as they frequently ‘guest’ on each other’s tracks.” Adams’s assertion is verified by examining sales charts in conjunction with track lists—for example, each of the ten best-selling rap albums of 2014 was released under the name of a solo artist, but all ten albums also featured multiple appearances from guest rappers (http://www.billboard.com/charts/year-end/2014/rap-albums). More generally, we can confirm this trend by examining rap singles that have reached the #1 position on Billboard’s “Hot Rap Songs” chart since 1990. Figure 2 shows the dramatic decrease in chart prominence of rap groups over time, and the increased share of overall chart-topping songs released by a solo rapper and featuring at least one guest rapper. The decrease in the overall number of rap singles in each consecutive column can be attributed to the increased staying power of singles in recent years, compared to the variability of chart-topping songs in the 1990s. In other words, a song that reached the top spot in the 1990s was less likely to occupy that spot for many consecutive weeks, as opposed to the 2000s and 2010s, where especially popular singles occasionally topped the charts for more than ten weeks at a time. Despite the decline in prominence of rap groups, the hip-hop industry is still peppered with collectives such as G-Unit, Black Hippy, ASAP Mob, and numerous other loosely-affiliated groups of rappers that regularly collaborate, both in the studio and on tours. Group affiliation extends beyond this explicit connection and into implicit designations, such as hip-hop’s well-known “East Coast vs. West Coast” dichotomy, referring to the competing “schools” of rap originating in New York and Los Angeles, respectively.

[0.5] It is important to acknowledge that nearly every contemporary rap track represents an accumulation of influence spanning decades. Intra-track relationships aside, rappers are often candid about the ways in which their deliveries and musical styles are shaped by their mentors or predecessors. In an interview, rapper Rock (half of the rap duo Heltah Skeltah) mused that “every rapper [

[0.6] Thus, the concepts of group membership, intra-genre references, and collaboration are fundamental components of the hip-hop genre. In what follows, I investigate the ways in which these connections between rappers manifest themselves musically. Through careful transcription of numerous rap tracks featuring multiple artists, I demonstrate the tangible ways in which the idea of collaboration—one central to the identity of hip-hop culture in general—is exemplified in the intra-track relationships between the performances of various rappers. I examine not only the extent to which collaboration can influence the delivery of lyrics on a rap track, but also the specific ways in which rappers signal the impact of their collaborators on a given track through the manipulation of their own flows.

1. Preliminaries, Terminology, and Analytical Precepts

[1.1] Before proceeding to my analyses, it will be useful to establish various notational and theoretical definitions, beginning with the term “flow.” Adam Krims defines “flow” as “an MC’s rhythmic delivery” (2000, 15). Kyle Adams states that flow is “all of the rhythmical and articulative features of a rapper’s delivery of the lyrics” (2009, [6]). Adams has divided flow techniques into two general categories: “metrical” and “articulative,” noting that his “metrical techniques of flow” are easiest to quantify (2009, [8–9]). He lists the metrical techniques of flow as follows (2009, [8]):

- The placement of rhyming syllables.

- The placement of accented syllables.

- The degree of correspondence between syntactic units and measures.

- The number of syllables per beat.

When writers describe a rapper’s flow, typically they are discussing parameters that would fall under the category of “metrical techniques,” such as rhyme schemes, end-rhyme technique, rapping speed, and rhythmic figures.(9) In the analyses that follow, I am primarily concerned with the metrical techniques employed by each rapper. I follow most recent rap scholars—including Adams—in not considering “articulative techniques” in my analyses because they involve characteristics such as legato, consonant articulation, and microtimings and are considerably more difficult to quantify (2009, [8]).

[1.2] As this project involves drawing connections between significant techniques employed by rappers, it is important to distinguish those techniques from what would be considered insignificant features of a rapper’s delivery. While many norms of rapping have long been generally understood, Nathaniel Condit-Schultz (2016) has worked to empirically confirm many of these principles via a corpus study of 124 rap tracks from the Billboard Top 100 chart between 1980 and 2015. Through Condit-Schultz’s analysis of this corpus, we can consider the following characteristics to be norms of rap:(10)

- The “typical pace of rap deliveries” is approximately 4.5 syllables per second (2016, Fig. 5).

- “Approximately one quarter of stressed syllables [

. . . ] are rhymed” (2016, Fig. 7).(11) - Rhymed syllables are most likely to occur on beat 4 (2016, Fig. 10).(12)

In light of Condit-Schultz’s study, I do not consider any of the above features to be significant or marked in my own discussion of collaborative flow in rap music, and instead focus my analytical attention on commonalities in rap flows that fall outside of these norms.

[1.3] This article features several examples of highly unified flow in select rap tracks, which is not typical of rap music. During my search for examples of closely collaborative flow techniques in tracks with two or more rappers, I discovered that it is much more common for rappers sharing a track to perform with differentiated flows that have little or no marked commonalities, with the exception of the rap norms identified by Condit-Schultz (2016) and Adams (2009).(13) It is possible—probable, even—that many listeners will hear most verses performed by guest rappers as sharing significant commonalities with those of the lead artist, but many of those commonalities are simply norms of the rap genre (Condit-Schultz 2016). Most rap verses indeed share characteristics, but drawing connections between normative flow techniques is no more significant or helpful than pointing out that two string quartets are similar in their instrumentation. The tracks in this article exemplify greater-than-normal unity of flow, with clear signs of rappers manipulating their deliveries to cohere with other artists on the track, presenting a cohesive series of verses reminiscent of early rap groups. My focus is on marked commonalities between rap flows, rather than aspects that are stylistically typical, though there are occasionally characteristics of flow that fall in between these two categories. Determining whether a rapping technique is due to stylistic norms or to a specific influence is at the heart of this study, and I hope to convince readers that the latter is at work in the analyses that follow.

[1.4] As a final note before proceeding to my analyses, I will explain my method of notating rap flows. Let us return to Example 3, which reproduces a section of Nicki Minaj’s guest verse in “#TWERKIT.” Color-coding designates rhymed syllables,(14) which are the driving force behind the organization of rap lyrics. While these syllables often stand out simply due to the fact that they rhyme, rappers also signal parallelisms between rhymed lyrics in any or all of the following ways:

- Rhyming groups are set in similar metrical locations.

- Rhyming groups are set to similar rhythmic figures.

- Rhyming groups are emphasized or articulated in similar ways.

My transcriptions highlight only rhymed syllables that have been additionally marked in one of these three ways. For example, while the syllables “see” (m. 1, beat 3.1) and “di” (m. 8, beat 1.2) technically rhyme, they are not marked in Example 3 because it is improbable that any listener would hear them as being connected—they occupy different metrical locations, are not stressed by Nicki Minaj in any marked way, and are simply separated by too much time for listeners to associate them. Ohriner (2016) asserts that there is likely an upper temporal limit beyond which listeners cannot perceive lyrics as being connected via rhyme. Likewise, he observes that there is an experiential lower limit for rhymed syllables occurring directly after one another. For example, the words “see” and “me” in Example 3 (m. 1, beats 3.1 and 3.2) are technically rhyming syllables, though they are not color-coded as such, because their immediate succession makes them unlikely to be perceived as a marked rhyme by listeners.

[1.5] I have placed numbers above certain syllables to denote compound (i.e., multisyllabic) rhymes when necessary: for example, the phrases “yuh fi do” and “heavy too” on the final beats of mm. 1 and 2 are three-syllable rhymes, and have been marked as such. Numbered syllables of similarly-colored polysyllabic rhymes will rhyme; for example, both of the syllables marked with a number “2” in the aforementioned three-syllable groups rhyme with each other.

[1.6] I refer to specific metrical locations using the decimal system “x.y,” in which x (a number between 1 and 4) denotes the beat within a given measure, while y (also a number between 1 and 4) refers to the sixteenth-note subdivision within given beat x. For example, the metrical location of the word “how” in m. 3 of Example 3 is beat 2.3—the third sixteenth-note subdivision of the second beat of that measure. The first syllable of the word “respect” in the same measure occurs at beat 1.1.

[1.7] Methods of notating rap flows have been impressively diverse amongst the music-theoretical community, including grid-based flow diagrams (Adams 2008, 2009, and 2016), linear timelines (Ohriner 2016), and rhythmically-oriented tables divided by metrical subdivision (Krims 2000).(15) Each of these methods of notating rap music is analytically useful in its own right, but for the purposes of my study, I have found that more conventional transcriptions of rap flows are the clearest way to demonstrate how specific metrical techniques are shared by multiple rappers performing on the same track.

2. Collaborative Flow in Early Rap Groups

[2.1] Rap groups such as Run-D.M.C., Public Enemy, Wu-Tang Clan, and A Tribe Called Quest played a large role in shaping rap music during its initial two decades.(16) Analysis of selected songs from relatively early rap groups reveals that unified flow techniques were commonplace during rap’s formative years.

[2.2] This overall unification of flow between rappers is apparent in the track “I’m Not Going Out Like That,” released in 1988 by Run-D.M.C, one of early rap music’s most influential groups.(17) Example 4 is a transcription of a verse from this track that is delivered solely by the rapper Run. Run’s method of organizing quatrains of text follows a normative pattern of ending four measures in a row with the same rhyming syllables(18)—note how the two-syllable word “whether” on beat 4.1 of m. 1 rhymes with the subsequent syllables occurring on beat 4.1 of the following three measures. Each of these end-rhymes is rhythmically unified as well. The seemingly more fluid rhymed groups that occur before beat 4.1 of each measure are less predictable. These are seemingly used indiscriminately, with little structural significance and no apparent connection to the rhymes on beat 4.1. Most striking about this passage is the rhythmic cell that Run relies on throughout his verse (Motive B, shown in Example 4b). Run vocally accents this six-note rhythmic motive in every measure of his verse. Motive B—with various unaccented additions to accommodate extra syllables before and after emphasized beats—is highly marked in this style, due largely to its incessant repetition from bar to bar.

Example 4a. Run’s verse in Run-D.M.C.’s “I’m Not Going Out Like That.” (click to enlarge and listen) | Example 4b. The principal rhythmic motive of the track “I’m Not Going Out Like That” (1988) (click to enlarge) |

Example 5. D.M.C.’s verse in “I’m Not Going Out Like That”

(click to enlarge and listen)

[2.3] Example 5 shows a transcription of D.M.C.’s subsequent verse. The commonalities between D.M.C.’s delivery and Run’s are immediately apparent: Motive B pervades every measure of D.M.C’s verse, and he structures his flow in a way that makes it rhythmically indistinguishable from his group mate’s performance in the previous verse.(19) D.M.C.’s flow can only be differentiated from Run’s via a rhyme-scheme analysis—while Run favors quatrains in his verse, D.M.C. relies on couplets in his. Nonetheless, both rappers employ the same technique of placing various rhymed syllables in each measure before the structural rhyme on beat 4.1.

Example 6. The Final verse of “I’m Not Going Out Like That,” performed by both Run and D.M.C. in unison

(click to enlarge and listen)

[2.4] The final verse of “I’m Not Going Out Like That” (Example 6) reinforces the notion that both rappers are intentionally performing with a strongly unified flow. While a high degree of collaboration was implicit throughout the earlier verses, in the last verse, the two rappers make their collaboration explicit, and rap the final sixteen bars in unison. Example 6 shows that the pair’s joint verse exhibits nearly all of the characteristics of the previous verses. This verse contains four rhymed quatrains structured around a two-syllable, rhythmically identical end-rhyme that occurs on beat 4.1.(20) Every measure is set to the same principal rhythm as the prior verses, Motive B. Significantly, each measure features a rhythmically “pure” version of Motive B—the rhythmic cell is heard sixteen times in a row, each time completely unadorned by the various unstressed additions that characterized the other verses. While each rapper’s metrical techniques of flow were relatively unified in the previous verses, it seems that their real-time collaboration in the final verse results in an even more unified structure: every measure in this verse has the exact same rhythm and number of syllables. In addition to these parallelisms, Example 6 also features the same flexible rhymed groups that appear before beat 4.1 in many measures, like those in Examples 4 and 5.

Example 7. A transcribed excerpt from Pos’s verse in “D.A.I.S.Y. Age” (1989)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[2.5] A similar, near-total level of flow cohesion can be observed in the track “D.A.I.S.Y. Age” (1989) by De La Soul, another influential early rap group.(21) Example 7 is a transcription of the track’s opening six measures, performed by rapper Posdnuos (frequently shortened to “Pos”). Pos’s flow in Example 7 is not particularly marked for complexity with respect to rhythm or rhyme, but it does exemplify highly unusual poetic syntax. While couplets, quatrains, and binary constructions in general are by far the favored units of poetic structure in rap music, Example 7 shows two nearly-parallel three-measure units, forming a sestet—a six-measure unit. Rhyme connections are shown via color-coding, and rhymed pairs exist between the following beats:

- Beat 3 of both m. 1 and m. 4

- Beat 1 of both m. 2 and m. 5

- Beat 3 of both m. 3 and m. 6

- Beat 3.3 of m. 2 and beat 1.3 of m.3

- Beat 3.3 of m. 5 and beat 1.3 of m. 6

Thus, while the exterior rhymes of each three-bar unit (shown in red and green) correspond with one another, both three-measure groups also contain a local couplet (shown in yellow and blue).

Example 8. A transcribed excerpt of Dove’s verse in the track “D.A.I.S.Y. Age”

(click to enlarge and listen)

[2.6] When rapper Dove takes over the performance of “D.A.I.S.Y. Age” in the song’s next verse, we can discern no audible change in metrical techniques or overall organization. Example 8 shows that Dove chooses to deliver a verse with the exact same construction as his group mate Pos in the previous verse. As in Example 7, Example 8 shows two three-bar units, each rhyming nearly perfectly with each other, apart from a brief interior couplet in each three-measure group. The rhythmic cells and metrical placement of each corresponding rhymed pair is nearly identical to the excerpt in Example 7, showing a marked cohesion between the two rappers.

[2.7] The reasons for early rap groups’ exhibiting the high level of flow unity epitomized in the previous examples are varied and largely uncomplicated. In his interviews with various members of rap groups, Paul Edwards spoke to several rappers about the process of co-writing a song with group members. Rapper Styles P, a member of the rap group The LOX, spoke candidly about the advantages and disadvantages of co-writing, stating that “you have less work to do, but then you also have to ensure that you’re up to par with your partners” (Edwards 2009, 214). Lord Jamar, one-third of the group Brand Nubian, expressed a similar sentiment regarding writing as a group, saying: “The pros might be that you write less. The cons are that you have to sometimes compromise what the whole thing might be about or something to appease everybody’s tastes…” (Edwards 2009, 213). In Edwards’s series of interviews, many rappers imply that ideas for flow or rhyme construction are freely passed between members of a rap group. Rappers Havoc and Prodigy, who comprised the group Mobb Deep until Prodigy’s unfortunate passing in June 2017, considered themselves a “family,” and Havoc states: “Oh yeah, for sure, I wrote verses for Prodigy, and he wrote verses for me” (Edwards 2009, 215). In light of these interviews, it is perhaps unsurprising that early rap groups have extremely unified flows between the individual performers on a given track. Indeed, there are numerous examples of rappers performing a lyrical back-and-forth with one another within a single verse, where one artist may finish the other’s line or chime in on an emphasized word, as opposed to the examples in this article, where each verse is mostly left to a single rapper to perform.(22) This type of collaboration is largely explicit through their membership in a rap group, and implicit through their shared flows. In short, we can expect mostly-unified metrical techniques of flow in tracks by early rap groups because many of them “wrote everything together” (Edwards 2009, 216).(23)

[2.8] In analyzing rap music, the looped backing track of a given song (colloquially referred to as the “beat”) should be considered in addition to a rapper’s delivery of lyrics. Adams (2008) posits that a rapper’s flow can be influenced by the beat over which they are rapping, resulting in artists incorporating and reacting to motivic elements, drum patterns, and even harmonic changes in their flows. It logically follows that some commonalities between rappers’ flows can be explained by examining a track’s beat, which in nearly all cases is a unifying element in itself. Several analyses below address the possible influence of a song’s beat on its performers. However, explaining collaborative flow is not as simple as noting musical elements that are transferred from a backing track into a rapper’s performance. In the case of De La Soul’s “D.A.I.S.Y. Age,” for example, neither the principal rhythmic figures nor the unusual three-bar construction are easily explained by examining the song’s sparse beat. The flow commonalities in “D.A.I.S.Y Age,” as well as other analyses that follow, are more likely due to a degree of conscious collaboration between artists than characteristics of the track’s beat.

Example 9. A transcribed excerpt from Lauryn Hill’s verse in “How Many Mics” (1996) by the Fugees.

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 10. A transcribed excerpt from Wyclef Jean’s verse in “How Many Mics”

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 11. A transcribed excerpt from Pras’s verse in “How Many Mics”

(click to enlarge and listen)

[2.9] Not all early rap groups demonstrated collaboration through unified flow techniques. Indeed, one of the principal advantages of collaboration in hip-hop is the opportunity “for making something interesting and diverse—more input, more variety, more levels of thought

[2.10] While some commonalities do exist among the flow transcriptions above, there are also marked differences between each rapper’s flow and those of their group mates.(24) For example, Hill eschews rap conventions regarding the organization of rhymes, in that rhymed groups often occur in various metrical locations rather than primarily on the fourth beat of each measure. Additionally, no single rhythmic cell takes primacy in Hill’s flow, and her performance is noticeably behind the beat—a purposeful rhythmic looseness that results in a speech-like cadence.(25) Finally, Hill’s rhymes do not form clear sections or stanzas; instead, there is frequent “nesting” of rhymes, in which a new rhymed pair disrupts the prevailing pattern, only for the original rhyme to return later (see mm. 4–6 of Example 9).

[2.11] Contrary to Hill’s rhythmically varied and loosely organized flow, both Wyclef Jean and Pras demonstrate a more conventional placement of rhymed syllables primarily on the fourth beat of a given measure (Condit-Schultz 2016).(26) Both of Hill’s bandmates favor single-syllable rhymes, in contrast to Hill’s frequent employment of polysyllabic rhyming groups. Despite these commonalities between Wyclef Jean and Pras, the two rappers do markedly differentiate their flows from one another—Jean favors two-measure rhymed couplets (Example 10), while Pras focuses on a single rhymed syllable for six measures before altering his rhyme choice (Example 11). Each rapper has their own rhythmic signature as well: Jean favors swung sixteenth notes as his primary rhythm, while triplets take primacy in Pras’s delivery.(27)

[2.12] It is unsurprising that her bandmates did not conform to Hill’s flow in “How Many Mics,” for her rapping exhibits a relatively high degree of intra-verse disunity. Since she does not rely on any single rhythmic cell, end-rhyme technique, or rhyme scheme in her verse, her flow is perhaps best characterized by its very lack of unity. Thus, it is difficult to imagine what it would sound like if Jean or Pras were to attempt to make their flow cohere with that of Hill—how does one imitate a style that is defined primarily by its variability? This leads me to a point that will be crucial in Section 3 of this article: for one rapper to match their flow to another’s, the style of flow that is being imitated must be unified within itself, exhibiting regular rhythmic or rhyme patterns that can be co-opted by another rapper.

[2.13] While some early rap groups wished to convey collaboration or a sense of close group cohesion via unified flow techniques (as in Examples 4–8), other groups aimed to portray each member of the ensemble as an individual with specific musical signatures differentiating them from their bandmates (as in Examples 9–11). A cursory glance through the history of rap music reveals several groups that demonstrate markedly disunified flow techniques.(28) Rap groups with less-unified flow techniques seem, in retrospect, to foreshadow the future of the genre: from the 1990s through the 2000s and beyond, rap groups decrease in prominence and solo artists that frequently feature guest rappers commensurately increase in prominence. Over time, there is also an increase of what Paul Edwards refers to as “posse tracks,” or tracks “in which numerous rappers (normally more than four or five) all contribute to a single track, usually doing back-to-back verses, in which the next artist starts rapping immediately after the previous MC” (Edwards 2009, 221). However, while traditional rap groups have faded in contemporary hip-hop, there are still numerous examples of collaborative flow in recent tracks released by solo artists that feature one or more guest rappers, as I will demonstrate in the following section.

3. Analyzing Musical Relationships between Lead and Guest Rappers

[3.1] As shown in Figure 2, rap tracks featuring guest rappers are ever more common. Rappers cite various advantages of appearing as a guest on a given track. According to the rappers that Edwards interviewed, many of these advantages take the form of a friendly competition, thereby increasing the quality of all of the involved artists’ writing. For example, rapper Rah Digga enjoys working as a featured artist, “because the object is to sound better than them, so it’s more fun, it’s more challenging, it’s more of a sport” (2009, 224). Big Daddy Kane expressed a similar sentiment, saying that “when you surrounded by talent, it’s gonna keep you on your toes, and also it makes the whole thing fun” (Edwards 2009, 223). It is apparent that there is a competitive aspect to recording a single guest verse that differentiates that experience from the one of performing in a more traditional rap group. While rap groups like Run-D.M.C. and De La Soul have waned in prominence, the importance of collaboration and group membership is still significant enough in contemporary rap music that it can at times result in guest rappers altering their deliveries in order to present a flow that is relatively unified with that of a given track’s lead rapper.

“#TWERKIT” by Busta Rhymes (2013), featuring Nicki Minaj

Example 2. A transcribed excerpt of Busta Rhymes’s performance in “#TWERKIT” (2013)

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 3. A transcribed excerpt of Nicki Minaj’s guest verse in Busta Rhymes’s track “#TWERKIT”

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.2] The concept of collaborative flow between lead and guest rappers is readily illustrated by returning to Examples 2 and 3, excerpts of Busta Rhymes and Nicki Minaj’s verses from “#TWERKIT.”(29) A closer analysis of Examples 2 and 3 reveals a level of flow unity comparable with the previous examples from Run-D.M.C. and De La Soul. Both rappers frequently employ rhythmic Motive A (Example 2b)—a short-short-long figure—especially on the beats 1.1 and 4.1 of a given measure. With regards to rhyme scheme, both rappers rely solely on rhymed couplets, with no overlap between rhymed groups. In an extremely marked articulative choice, Nicki Minaj and Busta Rhymes deliver the entirety of their verses using the aforementioned Caribbean patois accent and grammatical structure, although neither performer uses this accent in their day-to-day speech or in much of their other recorded work.(30)

[3.3] Pitch aspects of rapping are some of the least remarked-upon in rap analyses. However, relative pitch plays an important role in identifying commonalities between the flows of the lead and guest rapper in “#TWERKIT.” In each verse, the rapper begins by performing the initial four bars in a relatively high vocal range—especially Busta Rhymes, who raps near the top of his spoken register. After exactly four measures, in a moment that corresponds with the arrival of bass hits in the backing track, each rapper shifts their vocal range markedly downwards, clearly incorporating an aspect of the song’s beat into their flow, a phenomenon noted by Adams (2008). The change is most dramatic in the flow of Busta Rhymes, who shifts into a low, rumbling vocal fry for the remainder of his verse. Nicki Minaj’s downshift in range is not as drastic, and she is aided by double-tracking (i.e., superimposing a second recording of the same passage)(31) on certain words (see the bolded lyrics in Example 3). Generally speaking, double-tracking is employed by rappers and producers when they want to make a section of flow sound “fuller and stronger” (Edwards 2009, 282). Lower-pitched rapping also has connotations with strength and dominance. As Edwards asserts, rapping in a low range “gives the voice more weight and authority” (2013, 62). It is likely that double-tracking was employed solely during Nicki Minaj’s verse in “#TWERKIT” to help her match the weight and contrast of Busta Rhymes’s vocal shift, as her vocal range of course extends nowhere near as low as his. Regardless of the specific impetus behind any of the decisions regarding Nicki Minaj’s flow as a guest rapper on Busta Rhymes’s “#TWERKIT,” the end result is unquestionably an invocation of the same type of strongly unified flow from early rap groups that was used to indicate membership and collaboration.

“Blood Hound” by 50 Cent (2003), featuring Young Buck

Example 12. The first of the only two rhyme schemes employed by rapper 50 Cent in the entirety of his track “Blood Hound” (2003)

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 13. The second of the two rhyme schemes employed by 50 Cent in “Blood Hound”

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.4] A similar alignment of style and structure between a lead rapper and their guest can be heard in rapper 50 Cent’s track “Blood Hound” (2003), on which he is joined by Young Buck, a fellow member of the rap collective G-Unit. Like the preceding example, 50 Cent adheres to an extremely rigid rhyme/metrical scheme in “Blood Hound,” structuring his rhymes in one of two ways (Examples 12 and 13). The first of 50 Cent’s rhyme schemes (Example 12) contains two four-bar units, each with an AAB organization. The corresponding rhymes are rhythmically linked as well, as in previous examples—i.e., both lines end with an emphatic, two-quarter-note rhyme on beats 1.1 and 2.1 of the fourth measure. I refer to these end rhymes—“mac mane” and “back mane”—as “partial repeat rhymes,” not true multi-syllable rhymes, as the word “mane” (i.e., “man”) is repeated in both sections of the couplet. 50 Cent’s second rhyme scheme (Example 13) is quite similar to the first, with one small difference: the rhymes occurring in the fifth and sixth bars of Example 13 do not correspond with those in the first and second bars, making this second scheme an AAB, CCB scheme, instead of two sets of AAB as in Example 12. Once again, 50 Cent employs a partial repeat end-rhyme in the fourth and eighth bars of his unit in Example 13. Every eight-measure unit of both of 50 Cent’s verses in “Blood Hound” adheres to one of these two schemes.

Example 14. A transcribed excerpt of Young Buck’s guest verse in “Blood Hound”

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 15. Young Buck imitates 50 Cent’s delivery, and employs the same rhyme scheme as shown in Example 12

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.5] A transcription of Young Buck’s verse in “Blood Hound” (Example 14) shows that once again, marked characteristics of the lead rapper’s flow have been adopted by his guest artist. Note the similarities between the construction of this verse and that of 50 Cent’s second rhyme scheme (Example 13): both share nearly the same AAB, CCB construction, and both end with a partial-repeat rhyme: while “line” and “fire” rhyme, the word “bro” is used to end each line, just as “out” is used to end each line of the excerpt from 50 Cent. Young Buck’s scheme emphasizes off-beats with his A and C rhymes (shown above in gray and yellow), but the overall structure is clearly directly influenced by the rhymes performed by 50 Cent in the previous verse. Sections of Young Buck’s delivery also closely mirror the first of 50 Cent’s rhyme schemes (Example 12), as shown in Example 15. The connection between 50 Cent’s delivery in Example 12 and that of his guest in Example 15 is implicit in the shared AAB, AAB construction. Young Buck only digresses from 50 Cent’s example in two ways: the number and spacing of A rhymes (shown in gray), and the fact that this example ends on a true compound rhyme, with no repeated words between the end rhymes “ri-d(ah)” and “find-ya.”

[3.6] “Blood Hound” is markedly unified in terms of rhythm, rhyme scheme, and end-rhyme technique. While the flows of 50 Cent and Young Buck are slightly less unified than the near-total cohesion seen in previous examples, the collaboration of the two rappers is clear, and “Blood Hound” functions as a musical demonstration of the group’s shared membership in the rap collective G-Unit.

“Forgot About Dre” by Dr. Dre (1999), featuring Eminem

Example 16a. Motive C

(click to enlarge)

Example 16b. A transcribed excerpt from Dr. Dre’s first verse in “Forgot About Dre,” exemplifying his reliance on Motive C (bracketed in orange)

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 17. An exemplary framed rhyme scheme in Dr. Dre’s first verse of “Forgot About Dre”

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 18a. Eminem’s alteration to Motive C forms Motive D

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 18b. Eminem’s reliance on Motive D during his guest verse in “Forgot About Dre”

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 19. Eminem’s development of Dr. Dre’s framed rhyme scheme (see Example 17)

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 20. Another Example of Eminem’s development of Dr. Dre’s framed rhyme scheme (see Example 17)

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.7] While the previous examples have been relatively straightforward examples of collaborative flow, my final example is considerably more complex, and extends far beyond guest artists merely parroting certain flow techniques of lead rappers. Eminem and Dr. Dre have been frequent collaborators ever since Eminem’s signing to Dre’s Aftermath Entertainment label in 1998. While the two artists frequently appear on each other’s albums and embark on tours and business ventures together, their flows on shared tracks exemplify the collaborative nature of their relationship on a deeper level.

[3.8] To unravel some of this relationship, I analyze one of the pair’s most well-known joint tracks, titled “Forgot About Dre” (1999). In this track, Dr. Dre performs the first and last verses, while Eminem appears as a guest artist on the middle verse. There are two principal characteristics of Dr. Dre’s first verse that are important for the discussion at hand. The first is a small rhythmic cell that saturates much of his performance (bracketed in Examples 16a and 16b), which I will henceforth refer to as Motive C. As shown in the transcription in Example 16b, Dr. Dre uses Motive C to underscore a plethora of two-syllable end-rhymes. The majority of end-rhymes in Dr. Dre’s first verse are set against Motive C, and nearly all of these are interchangeable “oh-ee” compound rhymes—i.e., “dough freeze,” “tro-phies,” “ho please,” and “smoke trees.” This feature, a combination of rhythm and end-rhyme technique, is important in the verses that follow.

[3.9] A second feature of this first verse warrants attention: Dr. Dre employs a specific type of rhyme scheme, referred to as an “enclosed rhyme” or “framed rhyme.” This setting of four lines of text (a quatrain) has an ABBA form, in which an interior rhymed couplet is sandwiched by two lines with a contrasting rhymed syllable, as in Example 17. This framed rhyme is notable not only for its end-rhyme organization, but also for its rhythmic unification. Notice that both of the A rhymes are set against the pervasive Motive C, and have the same rhyming syllables (“oh-ee”) as the compound rhymes shown in Example 16b. However, the interior couplet (shown in gray) contrasts not only in terms of rhyming syllables, but also in rhythm—each of the interior end-rhymes is set as a flurry of sixteenth notes.(32)

[3.10] An analysis of the rhythmic delivery and rhyme schemes in Eminem’s guest verse shows a clear influence from Dr. Dre’s earlier verse. However, as the transcription in Example 18b makes clear, Eminem adds a further rhythmic element to his delivery. Like Dr. Dre’s first verse, Eminem’s is dominated by a single rhythm that he attaches to the majority of his end rhymes. Eminem’s principal rhythm is in fact a slight development of Motive C—he simply inserts a sixteenth note at the previously-elided third subdivision of a given beat, as shown in Example 18a. I refer to this new, tweaked end-rhyme rhythm as Motive D. Every time Eminem performs Motive D, he emphasizes the two notes of that motive that fall on the attack points of Dr. Dre’s Motive C, creating a strong aural link between the two rhythmic cells. Eminem relies heavily on Motive D throughout his verse in order to accommodate three-syllable compound rhymes, such as “walkin’ by,” “saw a guy,” and “Karl Kani.”

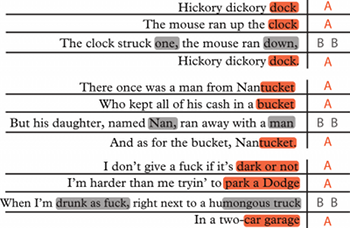

[3.11] Eminem’s development of Dr. Dre’s flow characteristics stretches beyond rhythm and into rhyme scheme. Eminem takes the framed, ABBA rhyme scheme performed by Dre in his first verse (Example 17) and mutates it slightly, while not changing it beyond recognition—just as he altered Motive C into Motive D. Example 19 is a rhyme-scheme analysis of a quatrain of Eminem’s verse. The first, second, and fourth measures of this quatrain are three-syllable compound rhymes: “dark or not,” “park a dodge,” and “car garage.” However, the third line is an abrupt insertion of two contrasting rhymes. Thus, Eminem has altered Dr. Dre’s earlier A-B-B-A form (seen in Example 17) into a polysyllabic A-A-b-b-A rhyme scheme. The forms are different, but both still contain interior rhymes that contrast their bookending lines, and both rely on Motive D for each end-rhyme. Another example of Eminem’s version of a framed rhyme can be seen in Example 20. In this example, the exterior rhymes, shown in orange, match one another not only in syllables, but also in rhythm—as do the contrasting interior rhymes. In performing this particular rhyme scheme, Eminem invokes a poetic form that, while being quite well-known, is scarcely heard in rap music—namely, the “limerick” rhyme scheme; familiar to us from such classics as “Hickory Dickory Dock” and “The Man from Nantucket”—see the comparisons in Example 21.(33)

Example 21. Examples of the limerick throughout history (click to enlarge) | Example 22. A transcribed excerpt from the third verse of “Forgot About Dre” shows Dr. Dre’s reliance on Eminem’s Motive D (click to enlarge and listen) |

[3.12] Both the limerick-inspired development of Dr. Dre’s framed rhyme scheme and Eminem’s reworking of Motive C into Motive D are significant for what comes next in “Forgot About Dre”—the song’s final verse, Dr. Dre’s answer to Eminem. The extent to which Eminem’s Motive D has impacted—and indeed, commanded—Dr. Dre’s flow. In the wake of Eminem’s alterations to the initial Motive C, Dr. Dre’s flow has completely absorbed this new, principal end-rhyme rhythm, and the first section of the verse is saturated with it, as shown in Example 22.

Example 23. Dr. Dre’s appropriation of Eminem’s “limerick” rhyme scheme

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 24. Dr. Dre’s appropriation of Eminem’s “limerick” rhyme scheme, with the characteristic rhythmic contrast in the interior couplet (highlighted in gray)

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 25

(click to enlarge and listen)

[3.13] In addition to borrowing Eminem’s principal rhythm, Dr. Dre appropriates his guest’s rhyme schemes. As shown in Examples 23 and 24, Dr. Dre employs the same limerick rhyme scheme used by Eminem in the previous verse (Example 20), assigning contrasting rhythms to his interior framed couplet (shown in gray) while relying on Motive D for the exterior rhymes (shown in orange)—a technique identical to that used by Eminem one verse prior.

[3.14] The limerick rhyme scheme is of harmonic significance as well in “Forgot About Dre.” The track’s harmonic progression (really more of an oscillation) is a four-measure loop. The harmonies are played by synthesized strings: G minor for the first two bars,

[3.15] “Forgot About Dre” demonstrates what appears to be a chain of musical influence that passes between the song’s two rappers, from one verse to the next. Dr. Dre puts forth an initial set of rhythms and rhyme schemes, which are elaborated upon by Eminem in the second verse, and then Dr. Dre responds in kind in his final verse by confirming, via his own flow, Eminem’s influence on the track. The relationship portrayed in “Forgot About Dre” is markedly more dynamic than any of the previous examples. Rather than a guest rapper closely imitating the flow of a track’s lead artist, this is a musical dialogue between the two artists, complete with exchanges and developments of rhythmic cells and rhyme schemes.

[3.16] At this point, readers should be reminded that the level of flow cohesion between lead and guest rappers exemplified in the previous examples by Busta Rhymes, 50 Cent, and Dr. Dre is uncommon. While sifting through recent rap albums in preparation for this article, I noticed that guest rappers seem more likely to perform with a flow that markedly diverges from a lead rapper’s style. This is unsurprising, as rappers spend time developing unique styles, and one can imagine that a guest rapper would be brought onto a track in hopes of diversifying it to a certain extent. This makes the examples above all the more significant—rather than showcasing the diverse styles or talents of a guest rapper, each track instead calls to mind the highly-unified flows of old-school rap groups.(34)

4. Why does this happen?

[4.1] There are several possible explanations for the persistence of group-inspired, collaborative flow techniques outside of the domain of a traditional rap group. In discussions with colleagues and rap aficionados, the idea of a guest rapper’s being subconsciously influenced by the delivery of a track’s lead rapper has continuously arisen. From a cognitive standpoint, the possibility of a rapper having metrical techniques of flow subconsciously imposed upon them by another artist is certainly a fascinating one. This theory would also forge exciting paths to other disciplines, with an especially relevant thread of scholarship in linguistics. “Communication accommodation theory,” or simply “accommodation theory,” is an oft-researched linguistic concept that “claims that speakers will attempt to converge linguistically toward the speech patterns of the addressee when they desire social approval from the addressee, given that the perceived costs of doing so acting are proportionally lower than the rewards anticipated” (Azuma 1997, 189). This theory typically revolves around issues of regional accents, and posits that speakers who are empathetic or seeking approval will subconsciously alter their accents to cohere with that of the person they are addressing. The parallels between accommodation theory and collaborative flow in rap music hardly need spelling out—if this theory applies to speech, should not it be possible that it also applies to rap flows? After all, rapping often invokes speech, despite its reliance on a regular rhyme structure, rhythmic cells, and a background beat pattern. Could it be possible that guest rappers, subconsciously seeking the approval of a track’s lead artist, alter their cadence so as to better cohere with their collaborator?

[4.2] As interesting as this linguistic theory may be, I am skeptical about its applicability to rap music. This explanation of collaborative flow minimizes the creative agency of the artists. Additionally, we have plenty of indications from rappers that the decisions surrounding flow construction are anything but subconscious. Many of the examples of collaborative flow that I have discussed in this article likely exist due to some level of conscious collaboration. Rapper Imani, a member of the rap group The Pharcyde, states: “I’m used to working with partners and having people to bounce off of” (Edwards 2009, 215). King Mez, who both appeared as a featured rapper and ghostwrote lyrics for Dr. Dre’s 2015 album Compton, said that Dr. Dre “coached my voice into sounding like what he wanted his voice to sound like on every song” (Tardio 2015), a revelation that can point simultaneously to the nature of ghostwriting and to the rapper’s unified flows on shared tracks.

[4.3] Indeed, there are ample examples of rap tracks in which determining the writer of a given passage is no easy task. Ghostwriting (i.e., “when one artist writes lyrics for another to perform [Edwards 2009, 227]) is ostensibly common in the hip-hop sphere, albeit surrounded by a haze of obfuscation and negative connotations—for obvious reasons, rappers generally prefer to be the perceived writers of the lyrics they record. The process of ghostwriting necessitates a high level of collaboration in its own right. Rappers who have worked as ghostwriters discuss the need to tailor their writing so as to fit the style (or perceived style) of their client. Rapper B-Real notes that “you gotta be careful not to write your style for them. You have to give them something different so they don’t just sound like what you doing—you have to give them something completely customized for them” (Edwards 2009, 227). Chuck D of Public Enemy spoke openly about his ghostwriter in an interview, saying “Paris kind of wrote in a way that was reminiscent of earlier work that I’ve done [

[4.4] Ghostwriting, which should be an innate consideration when dealing with rap music, is a complicating factor when it comes to analysis. Lyrical authorship can be difficult to determine. Even Dr. Dre, a prodigious producer and hip-hop entrepreneur, has a reputation for frequently bringing in handfuls of rappers during his album-writing sessions, treating the task of inventing flows as a team exercise. Rapper RBX claimed that “Dre doesn’t profess to be no super-duper rap dude [

[4.5] However, questions of lyrical authorship or authenticity, while interesting in their own right, are tangential to this discussion. Whether the verses in any of my examples were written by guest rappers for themselves or written for a guest rapper by the lead artist or a third party, the fact remains that someone thought that unified flow was important in each example. In performing a given verse, a rapper implicitly endorses the flow techniques and lyrical content therein. When undertaking any type of popular-music analysis, there will always be questions of authorship hanging overhead. Indeed, it is not uncommon for a four-minute pop song released by a solo artist to have several people credited as writers—Beyoncé Knowles credits an astonishing eight people as co-writers of her single “Drunk in Love.” Thus, it is useful for analysts to differentiate between a work’s actual author(s) and its implied author(s).

[4.6] The “authority” of authorship, Lori Burns writes, is “ascribed,” in that it is possible to undertake layered analyses in which we engage on one level with whomever was responsible for constructing a given passage of flow, and on another level with the artist that is perceived as the owner or author of said flow (2010, 156). In all popular music, the primary artistic object is not an abstraction or score from which we can divine creative processes or intentionality—audiences engage solely with a recorded track, which is the only “authentic” object to analyze.(36) It is possible to engage with a rapper’s performance while acknowledging that we are analyzing the flow techniques in a way that disentangles the performer from the author. In this vein, Savage states that in analyzing sound recordings, we might assert that a “composition is a result of the process of recording and editing rather than a precursor to it”—that is, uncovering the complex network of individuals and technologies responsible for a given recorded track should be secondary to analyzing the track itself (2011, 5). Indeed, the order of composition on rap tracks is often difficult or impossible to know for certain. The music is usually composed before the lyrics (Adams 2008), but the order in which verses are written is not typically documented. This is to say: when it comes to the issue of authorship in rap music, the question of who wrote lyrics and when they were written is difficult to answer, so we should absolve ourselves from spending too much energy attempting to answer these questions. Regardless of who wrote the words being rapped by Dr. Dre at a given moment, it is still significant that he is presenting himself as the implied author of those lyrics, and the fog of uncertainty surrounding a track’s actual author should not impede us from engaging with the work of its perceived author.

Unity, Collaboration, and Conclusions

[5.1] It is clear that the concepts of collaboration, group membership, and unity are more than rhetorical tropes that surround the hip-hop genre. As I have demonstrated above, these concepts are tightly intertwined within the musical fabric of rap, altering the very construction of flows. Certainly, the concept of “unity” has a broad history in music-theoretical discourse.(37) Various types of musical unity have been detailed by writers, perhaps most prominently by Fred Maus (1999), and much of this discussion has focused on analytical privileging of (or resistance to) unity as being “important for a rewarding listening experience” (Williams 2009, [10]). Maus’s argument for the inclusion of unity in musical analyses centers on the notion that unity is central to the listener experience, and any analysis purposefully avoiding or downplaying the use of unity in a given work would thus be disregarding the experience of the listener. Robert Morgan offers a nuanced approach to the idea of musical unity, working to refute much of what he refers to as “the negative attitude towards unity” in recent scholarship (2003, 22). Unity, Morgan states, is “subjectively posited solely by the analyst, with no more value than any other judgement” (2003, 23).

[5.2] Despite the relative scarcity of unified flow in contemporary rap, especially when compared to rap music from the 1980s and 1990s, the type of collaboration shown in the analyses above is both a demonstrable and salient phenomenon in contemporary rap music, with a history and impetus that extends to the genre’s beginnings in closely-knit rap groups. In the burgeoning field of rap analysis, as we strive to become increasingly conversant with this relatively new genre of music, we have little choice but to prioritize the listener experience. After all, there is little else to analyze—most of rap is not notated, and our analyses must rely largely on our own transcriptions. The analyses above hint at a largely undiscovered network of influence and collaboration in rap music. Through an understanding of the nature and tendencies of collaborative flow in rap music, we can better grasp the nature of identity in hip-hop, and open new venues for research in this under-analyzed genre.

Robert Komaniecki

Indiana University

PhD Student, Department of Music Theory

1506 S. Dorchester Dr., Apt. 11

Bloomington, IN 47401

rdkomani@indiana.edu

Works Cited

Adams, Kyle. 2008. “Aspects of the Music/Text Relationship in Rap.” Music Theory Online 14 (2). http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.08.14.2/mto.08.14.2.adams.html.

—————. 2009. “On the Metrical Techniques of Flow in Rap Music.” Music Theory Online 15 (5). http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.09.15.5/mto.09.15.5.adams.html.

—————. 2016. “Playing with Beats and Playing with Cats: Meow the Jewels, Remixes, and Reinterpretations.” Music Theory Online 22 (3). http://mtosmt.org/issues/mto.16.22.3/mto.16.22.3.adams.html.

Anderson, Benedict. 1983. Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origins and Spread of Nationalism. Verso.

Azuma, Shoji. 1997. “Speech Accommodation and Japanese Emperor Hirohito.” Discourse and Society 8 (2): 189–202.

Chua, Daniel K. L. 2004. “Rethinking Unity.” Music Analysis 23 (2–3): 353–359.

Cohn, Richard and Douglas Dempster. 1992. “Hierarchical Unity, Plural Unities.” In Disciplining Music: Musicology and its Canons, ed. Katherine Bergeron and Philip Bohlman, 156–181. University of Chicago Press.

Condit-Schultz, Nathaniel. 2016. “MCFlow: A Digital Corpus of Rap Transcriptions.” Empirical Musicology Review 11 (2).

Edwards, Paul. 2009. How to Rap: The Art and Science of the Hip-Hop MC. Chicago Review Press.

—————. 2013. How to Rap 2: Advanced Flow and Delivery Techniques. Chicago Review Press.

Korsyn, Kevin. 2004. “The Death of Musical Analysis? The Concept of Unity Revisited.” Music Analysis 23 (2–3): 337–351.

Kramer, Jonathan D. 2004. “The Concept of Disunity and Musical Analysis.” Music Analysis 23 (2–3): 361–372.

Krims, Adam. 2000. Rap Music and the Poetics of Identity. Cambridge University Press.

Maus, Fred Everett. 1999. “Concepts of Musical Unity.” In Rethinking Music, ed. Nicholas Cook and Mark Everist, 171–192. Oxford University Press.

Morgan, Robert P. 2003. “The Concept of Unity and Musical Analysis.” Music Analysis 22 (1–2): 7–50.

Ohriner, Mitchell. 2016. “Metric Ambiguity and Flow in Rap Music: A Corpus-Assisted Study of Outkast's ‘Mainstream’ (1996).” Empirical Musicology Review 11 (2). http://emusicology.org/article/view/4896.

Savage, Steve. 2011. Bytes and Backbeats: Repurposing Music in the Digital Age. University of Michigan Press.

Shipp, Matthew. 2003. “El-P.” BOMB 85. 60–65.

Street, Alan. 1989. “Superior Myths, Dogmatic Allegories: The Resistance to Musical Unity.” Music Analysis 8 (1–2): 77–123.

Tardio, Andres. 2015. “Here’s What It’s Like to Ghostwrite for Dr. Dre.” <http://www.mtv.com/news/2240201/dr-dre-ghostwriter-king-mez/>

Weingarten, Christopher R. 2016. “Run-DMC on Receiving Rap’s First Lifetime Grammy Award.” http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/dmc-on-recieving-raps-first-grammy-lifetime-achievement-award-20160211

Williams, Justin A. 2009. “Beats and Flows: A Response to Kyle Adams, ‘Aspects of the Music/Text Relationship in Rap’” Music Theory Online 15 (2). http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.09.15.2/mto.09.15.2.williams.html.

—————. 2013. Rhymin’ and Stealin’: Musical Borrowing in Hip-Hop. University of Michigan Press.

Zak, Albin. 2001. The Poetics of Rock: Cutting Tracks, Making Records. University of California Press.

Footnotes

* My thanks to Kyle Adams, Brittany Olson, Anna Rose Nelson, Ryan Taycher, Kathryn Yuill, Nathan Blustein, Roman Ivanovitch, Diana Weinblatt, and the anonymous reviewers for their input and feedback on this article.

Return to text

1. Williams borrows the term “imagined community” from Benedict Anderson (1983).

Return to text

2. Examples of solo pop artists that began their careers with a band or group include Gwen Stefani (No Doubt), Justin Timberlake (N Sync), and Beyoncé Knowles (Destiny’s Child), to name but a few.

Return to text

3. Readers are warned that most of the rap songs analyzed in this article contain potentially offensive language. I will refrain from frequent commentary or value judgements regarding text. Following Kyle Adams, I “disregard the semantic meaning of the lyrics [

Return to text

4. I describe my method of transcription in detail in Section 1 of this article, but for now, readers need only be concerned with the characteristics described in this paragraph.

Return to text

5. A track’s lead rapper is the artist credited with the album. Track titling conventions usually differentiate between lead and guest rappers by using the following format: “Track Title,” by Lead Rapper, featuring Guest Rapper (i.e., “#TWERKIT” by Busta Rhymes, featuring Nicki Minaj). “Featuring” is commonly abbreviated as “feat.” (as in Example 1c).

Return to text

6. Patois, in this instance, refers to the quasi-Jamaican dialect adopted by both rappers—markedly different from the majority of their other recorded work. Several prominent early rappers were Jamaican (most notably Kool Herc, who is credited with catalyzing hip-hop music), and there is a long history of rappers adopting patois to reference the earliest performers in the genre. Examples of tracks in which rappers adopt patois include “Brooklyn (Go Hard)” by Jay-Z, “Lucifer (Remix)” by Lil’ Wayne, and “De Automatic” by KRS-One. Rap group Das Racist even released the track “Fake Patois” (2010), in which the group criticized rappers for appropriating the dialect.

Return to text

7. This is discussed briefly in Adams 2016, [8.4].

Return to text

8. Video: https://youtu.be/E6FKMBMNji8.

Return to text

9. Paul Edwards cautions that “end-rhyme” can at times be a misnomer, because not all rhymes in a given section of flow necessarily fall at the end of a syntactic unit (2013, 193).

Return to text

10. Condit-Schultz’s study goes into a much higher level of detail and identifies additional rap norms, but the three I have listed are most relevant to the present study.

Return to text

11. For a thorough explanation of what constituted “stress” in this study, see Condit-Schultz (2016).

Return to text

12. As Condit-Schultz says in his article, this is a phenomenon previously observed by Kyle Adams (2009).

Return to text

13. For examples of typical rap songs in which the guest rapper does not markedly cohere their flow with that of the lead rapper, see “On Me” by The Game feat. Kendrick Lamar, “Made Man (Visualizer)” by Big Boi feat. Killer Mike and Kurupt, and “Look at Me Now” by Chris Brown feat. Busta Rhymes and Lil Wayne.

Return to text

14. Adams (2009) first used color-coding to denote rhymed syllables.

Return to text

15. Adams, Ohriner, and Krims readily employ traditional transcriptions of rap flows as well.

Return to text

16. Rap music as we know it is generally thought to have begun in the late 1970s, though hip-hop’s “birthday” is considered to be August 11th, 1973.

Return to text

17. Run-D.M.C. consists of rappers Run (Joseph Simmons) and D.M.C. (Darryl McDaniels), who were joined by their D.J., Jam Master Jay (Jason Mizell).

Return to text

18. The final four measures of this verse break this pattern of rhymed quatrains, substituting two couplets instead.

Return to text

19. D.M.C. inches rhythmically towards a triplet-inflected flow in the final four bars of this example, but to my ear, this sounds more like rhythmically loose flow than a purposeful rhythmic shift.

Return to text

20. As with Run’s verse, this collaborative verse breaks the pattern of quatrains in the final four measures, opting instead for two couplets.

Return to text

21. De La Soul consists of rappers Posdnuos or Pos (Kelvin Mercer), Dove (David Jolicoeur), and Maseo (Vincent Mason Jr.), as well as producer Prince Paul (Paul Huston).

Return to text

22. Rappers cooperating to perform a single verse is a relatively common phenomenon and deserves further scholarly attention. For an example of a lyrical back-and-forth, see “Oh My Darling Don’t Cry” by Run the Jewels. For an example of group members joining in with a temporary lead rapper to emphasize certain words or lines, see “No Sleep Till Brooklyn” by the Beastie Boys.

Return to text

23. For more examples of unified flows in rap groups, see “Handle the Vibe” by Bone Thugs-n-Harmony, “Vibes and Stuff” by A Tribe Called Quest, and “Versace” by Migos.

Return to text

24. Many of the commonalities among Examples 9, 10, and 11 are in line with the rap norms outlined in Condit-Schultz’s 2016 study and are thus trivial.

Return to text

25. Hill’s flow is rhythmically loose enough that the transcription in Example 9 is only a close approximation, due to ambiguities presented by her penchant for rapping somewhat behind the beat.

Return to text

26. This clustering of rhymed syllables around the fourth beat in a measure can be seen in Condit-Schultz’s Figure 10.

Return to text

27. There is even a marked semantic difference between Hill’s rapping and her successors: Hill’s verse is peppered with similes (e.g., “red like a snapper” and “tame like the rapper”), while Jean and Pras do not use that rhetorical technique in their own verses.

Return to text

28. Some examples of early rap groups with a penchant for disunified (or less-unified) flows are Outkast, Cypress Hill, and the Roots. Two specific examples of songs with disunified group flows are “How Come” by D12 and “Understanding the Inner Mind’s Eye” by Leaders of the New School.

Return to text

29. For the sake of clarity, I will restate some of the characteristics of “#TWERKIT” that I called attention to in the introduction section.

Return to text

30. Nicki Minaj and Busta Rhymes do both have a degree of connection to the islands to which this patois is endemic—Nicki Minaj is Trinidadian, while both of Busta Rhymes’s parents are Jamaican. However, both rappers have been based in New York City for most of their careers, Busta Rhymes in Brooklyn, and Nicki Minaj in Queens.

Return to text

31. Also referred to as “doubling up,” “overdubbing,” or “stacking” vocals (Edwards 2009, 282).

Return to text

32. While the third syllables of both of the interior rhyme groups in this example do not technically rhyme, they are perceived as such. Paul Edwards describes the process of “rhythmic linking” to eclipse small discrepancies in rhymed groups (Edwards 2009, 90).

Return to text

33. While the rhyme scheme in this example mirrors that of a limerick, the number of syllables per line mostly do not.

Return to text

34. For more examples of guest rappers unifying their flow with that of a track’s lead rapper, see “House of Flying Daggers” by Raekwon feat. Method Man and Inspectah Deck, “How We Do” by The Game feat. 50 Cent, and “Gunshowers” by BADBADNOTGOOD and Ghostface Killah feat. Elzhi.

Return to text

35. A track from Dr. Dre’s 1992 album The Chronic.

Return to text

36. For a more thorough discussion on the concepts of “aura” and “authenticity” with respect to recorded works, see Zak (2001, 1-25).

Return to text

37. In addition to the sources cited below, see also Street (1989), Cohn and Dempster (1992), Kramer (2004), Korsyn (2004), and Chua (2004).

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2017 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Sam Reenan, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

31244