Parsimonious Voice Leading and the Stimmführungsmodelle

Ariane Jeßulat

KEYWORDS: diatonic voice leading patterns, partimento, neo-Riemannian theory, N-transformation, Parallelismus, Carl Friedrich Weitzmann, Simon Sechter, Josef Riepel, Montesequenz, Brahms “Feldeinsamkeit,” Schubert Symphony in C major D. 944, double agent complex

ABSTRACT: This article confronts the dialectic between parsimonious voice leading, as represented by neo-Riemannian theory, and the diatonic Stimmführungsmodelle, or the traditional formulas and methods of thorough-bass pedagogy as they were preserved in the nineteenth century. The historical contexts are represented by Carl Friedrich Weitzmann’s essay on the augmented triad (1853) and Simon Sechter’s Generalbass-Schule (1835). The possibility of setting the diatonic and chromatic models into productive analytic practice is explored, even as it is acknowledged that they are grounded in different principles. Steven Rings’s “syntactical interaction” and Richard Cohn’s “double syntax” are invoked. A Brahms song and a Schubert symphony serve as extended analytical examples.

DOI: 10.30535/mto.24.4.12

Copyright © 2018 Society for Music Theory

1. Historic and Systematic Aspects: Coexistence of Different Scientific Paradigms

1.1. Introduction

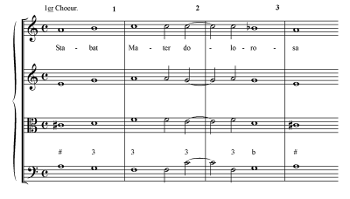

Example 1. Fétis, Traité, p. 158: Palestrina, “Stabat Mater,” opening

(click to enlarge)

[1] In the third book of the Traité complet de la théorie et de la pratique de l’harmonie, François-Joseph Fétis rejects the approach of his contemporaries as he emphasizes a stark change of paradigm from modal unitonalité to modern—that is, post-Rameau—approaches to tonality (1844, III, 158). Fétis asserts, for example, that the tonal organization of the opening of Palestrina’s “Stabat Mater” cannot be related to modern tonality at all, not in a single note—see Example 1. His uncompromising attitude is all the more remarkable in that most nineteenth-century scholars would not have missed an opportunity to interpret this cadence as a harmonic anachronism, to say nothing of the stepwise root progression in the three opening chords.

[2] The attentiveness to historical change that Fétis shows might also be useful in explaining a number of qualitative and categorical issues in the more recent history of music theory. Using the idea of parsimonious voice leading, this article discusses and compares the different categorical levels that an analysis must integrate within its scope when music theory confronts nineteenth-century patterns of voice leading that have lost contact with the eighteenth-century stylistic tradition of figured bass. An analyst may still be able to find traces of former partimento patterns in Romantic music (although it might require a certain degree of creative abstraction), but these are irreconcilable with the neo-Riemannian idea of the semitone as “minimal work unit” in triadic transformation. This intellectual gap separates not only two different perspectives of harmony and counterpoint (as shown by Fétis), but also represents a theoretical problem in itself.

[3] Renate Lachmann (1993, XX–XXVII) has described four paradigms for reconstructing culture by means of memory, two of which seem to conflict: the diagrammatic paradigm organizes knowledge systematically by means of the scientific method and various symbols with the aim of producing valid, universal models, but the mnemonic (or diegetic) paradigm forms the background for narrative and interpretative processing of data in the manner of the humanities and historical research. Parsimonious voice leading, being a tool belonging to the more systematic approach, is neither fallible nor open to interpretation, whereas traditional voice-leading formulas and historical compositional practice are more a question of musicological research and thus open for discussion.

[4] Lachmann’s model does propose that different research paradigms can coexist within a single project, thus, to our topic, allowing for and even suggesting the coexistence of stylistic perspectives beyond harmonic tonality (and resulting in a more benign construct than the situation in Riemann’s day, before the idea of historical contingency had been developed). For this reason, the model seems to be much better suited to today’s constant struggle to reconstruct history. The supposedly irreconcilable paradigms of traditional and parsimonious voice leading are bound to meld in every analysis, whether one seeks to suggest a composer’s intention, the reception of the music by contemporaries, or any other hypothesis serving as a springboard for the work. The meshing of paradigms is important especially in the case of Romantic harmony because the voice-leading models taught in theory and composition from about 1830 to 1910 were entirely wrapped up in ongoing speculative discussion about tonality (Sprick 2012). Thus, they were modified and, most importantly, abstracted.

1.2. Neo-Riemannian theories and analytical paradigms

[5] Neo-Riemannian theories replace the traditional logic of the tonal cadence (phrases based upon harmonic progressions of fundamental fifths) with harmonic textures containing minimal voice-leading work (that is, parsimonious voice leading), a model of triadic transformation that is a practical application of mathematical group theory. Minimal voice-leading movement serves as a basic tool to calculate triadic distance in a chromatic space. The idealized voice leading model is influenced by a general notion of pitch-class set theory: it adopts the equal-tempered semitone as the minimal work unit, rather than bestowing this label upon traditional chord progressions related by fifths.

[6] While neo-Riemannian theories explicitly adapt post-1850 German music theory, they also reinterpret historical music theory in an exceptionally creative way by linking two scientific paradigms that tend to be understood as incommensurable. The methods and syntax of neo-Riemannian theories originated from the diagrammatic paradigm (that is, from the scientific method), but examining and hermeneutically interpreting music theory developed during the Romantic era requires approaches more at home in the humanities (such as the mnemonic or diegetic paradigm; Lachmann 1993, XXV). Once one begins to see the relevant achievements of Idealist music theory as a substantial part of the cultural memory and self image of the Romantic era, traces of the mnemonic paradigm start popping up everywhere: in textbooks, in the iconography of their exercises and musical examples, and in the loci communes (rhetorical commonplaces) of different scientific and didactic approaches to the phenomenon known as tonality.(1)

[7] Additionally, the mnemonic paradigm provides a model to help us understand how concepts of music theory were taught in former times, a narrative that is marked by the rivalry between nascent historicism and a marked fascination with the overwhelming progress of science, especially in the time period that neo-Riemannian theories attempt to describe in a new and radical way (Schnädelbach 1987, 128).

[8] Thus it would seem inescapable that, in the confrontation between historical harmonic theory and its quasi-timeless, systematic revision, one’s perspective must oscillate between documentary and constructive methods (Schnädelbach 1987, 146–7). Therefore, an eclectic approach can be understood not as detracting from scholarly standards but as a part of the process of hermeneutic analysis.

[9] Even after thirty years, the novelty of the fusion of transformational theory with traditional theories of Romantic harmony sometimes makes one forget that scientific method is only one part of the model. The analytical focus, the aspects of Romantic harmony dismissed by the theory, and all analytic practice are based upon numerous historical, hermeneutic considerations and decisions. Despite the textbook-like construction, the high didactic quality, and the mathematics-based infallibility of its tools and diagrams, neo-Riemannian theories are founded upon the unstable device of superimposing mathematics on reinterpreted Romantic theory, a situation that serves to highlight the question of which aspects of historical theory are reinforced, reinterpreted, or even dismissed in the process of evaluating the adequacy of this approach for the musical situation examined.

[10] A single instance within the far-reaching and partly inhomogeneous field of neo-Riemannian theories will be discussed in part 2 below, but that will be sufficient to arrange a fruitful collision of transformational logic and concrete voice leading. I will use the theoretical perspective and terminology of a “Weitzmann region” as described by Richard Cohn in his study of the augmented triad and the underlying structures it generates in Romantic harmony (Cohn 2012). A clear distinction between categories will prove just as necessary as the controlled cross-fading thereof.

[11] The analyses of music by Brahms and Schubert that follow in part 3 will scrutinize two aspects of the augmented triad as found in neo-Riemannian theories. In doing so, critical comments aim to enrich the methods employed, while the interdependency of competing paradigms may sharpen our understanding of the cultural context.

2. Critique of Weitzmann’s Der übermässige Dreiklang (1853)

[12] Basic to my argument here is the observation that the augmented triad appears in at least two categories of music theory and pedagogy around 1850: in the first case as a trope of thorough-bass practice, in the second case as a focal point in the modern, speculative music theory that emerged from the circle of theorists led by Moritz Hauptmann. The discussion in the second instance was anything but homogeneous: Hauptmann adopted a timeless, philosophical perspective, but Carl Friedrich Weitzmann, although he took advantage of the systematic depictions and intellectual approach derived from Hauptmann, advocated the historically defined position of the stylistic avant-garde and musical modernity (Weitzmann 1853, 32; 1861, 1, 4, and passim). Highlighting the systematic and symmetrical aspects of Weitzmann’s publications, along with the obvious similarities between Weitzmann’s diagram-rich style and the general ideas of pitch-class set theory, represents a creative interpretation that can be found in some more recent American music theory.

2.1. Two different tropes of the augmented triad: 5–6 oblique motion and tonal dualism

[13] Despite its apparently systematic design, Weitzmann’s essay on the augmented triad leaves some gaps in its narrative, and the musical examples are noticeably inconsistent. Even a largely positive reviewer, writing in the May 1854 issue of the Niederrheinische Musikschrift (Reviewer D. 1854, 17), points out omissions in the essay’s historical sketch as well as some irregularities in the description of the triad’s “natural origin.” A possible explanation for these appropriately observed problems in Weitzmann's text could lie in the fact that he generally did not document information derived from his various sources and he added little or sometimes no commentary.

2.1.1. Consecutiva per quintam ad sextam

Example 2. Weitzmann 1853, p. 3

(click to enlarge)

[14] One of Weitzmann’s first musical examples presents the augmented triad as a transitory chord: The oblique motion from the fifth to the sixth is intensified by chromatic alteration of the fifth (Weitzmann 1853, 3). See Example 2. In the context of this voice-leading model, the sound of the augmented triad is a formula for ascending sequences already known in seventeenth-century rhetorical, gestural styles, and which by the nineteenth century had been long since established.

[15] In nineteenth-century music theory this Stimmführungsmodell is still alive as an exercise in thorough-bass pedagogy. Although the superficial similarity to parsimonious voice leading is striking, there is a categorical gap: the addition of chromatic passing tones to an existing contrapuntal texture is optional and may be done in order to intensify the musical expression. By contrast, chromatic triadic transformations through parsimonious voice leading are not a question of creativity and arbitrariness. The intermediate semitone step of the augmented triad bridging the R-transformation is not falsifiable in a scientific sense, but instead appears as an indicator of a source in a traditional voice-leading background.(2)

2.1.2. “Nebenverwandt“—remnants of dualism

[16] It is well known that the N-transformation is characteristic for the Weitzmann region (Cohn 2000, 92; 2012, 56, 61–62). Neo-Riemannian theories distinguish its transformational nature from the diatonic falling fifth of the chordal root by the label “nebenverwandt,” which was taken from the Weitzmann essay under discussion here. According to Cohn, the term “nebenverwandt” describes the transformation from a major triad into a minor triad one fifth below through the voice leading movement of two half-steps in the same direction. The mediation through an augmented triad that is one half-step away from each of the nebenverwandt chords is essential to the character of the transformation.

[17] The basic non-directional nature of neo-Riemannian transformations, however, makes it difficult to apply the N-transformation as an analytic tool. As a symmetric relation between a major triad and a minor triad one fifth below, the N-transformation loses contact not only with German music theory of 1850 but also with the “second nature” of transformations, which ought to qualitatively transcend a simple cadence.

[18] Here again, the origins of this inconsistency can be traced back to the relatively poor contextualization characteristic of Weitzmann’s essay.(3) In contrast to his first musical examples, which were offered as part of the historical sketch, he now proposes that the “natural origin” (natürliche Entstehung) of the augmented triad is derived from the dualist symmetry of a major chord and its minor subdominant chord as an inversion. In referencing this kind of symmetry, Weitzmann follows a tradition of music theories and textbooks since at least Marpurg’s translation and commentary of d ́Alembert’s Éléments de musique (Marpurg 1757, 14–6). Weitzmann almost certainly learned the system during his studies with Hauptmann and later from Hauptmann’s book (1853, 39), especially in the context of the dualist idea of Moll-Dur-Tonart. According to Hauptmann the Moll-Dur-Tonart is a tonal system (Tonartsystem) in which the tonic major triad and its negation, the minor subdominant triad, are opposite poles. It is notable, however, that he relaxes his strictly systematic mode of thought for just a moment in order to make a brief comment about style and the musical relevance of the Moll-Dur-Tonart:

Although this Moll-Dur-Tonart can hardly be considered the main key of a musical piece, it seems to be applied rather often in the course thereof; more frequently in the sentimental genre of modern music than in older music. This tonal system is present when the diminished seventh chord resolves into the tonic major triad; in fact, it is embodied wholly in the notes of these two chords. Likewise, it exists generally in the plagal cadence from the minor subdominant chord to the major triad of the tonic. This key has a diminished triad of the second scale degree, an augmented triad, and the augmented sixth chord in common with the minor tonality, and none of these chords refer specifically to a minor tonic. (Hauptmann 1853, 40, my translation)

[19] When Hauptmann discusses the augmented triad specifically, he again abandons his dualistic thinking for a few sentences to make some stylistic observations supporting his argument that the augmented triad is seated on the minor third of the subdominant. He points out that, in addition to the appearance of the chord in the Moll-Dur-Tonart on the third of the subdominant, there is an alternative origin, namely the chord A–C–E–

[20] Within his Moll-Dur-Tonart scheme, however, Hauptmann defines the relation that Weitzmann later describes in one instance as “nebenverwandt”—and from which Cohn later developed the N-transformation and the implications of the intermediary augmented triad—as explicitly vectorial, that is to say as the tension between a major tonic and the region of its minor subdominant intensified in the play with the chromatically altered sixth scale degree. (4)

[21] Weitzmann (1853, 16) discusses the Moll-Dur-Tonart only briefly and without context, so that the critic of 1854 took him to task for unexpectedly putting the “natural origin” of the augmented triad on the third of the minor subdominant chord instead of simply altering the fifths of the tonic, dominant, and subdominant chord. The reviewer continues:

[Weitzmann] writes further that “In major tonality it (the augmented triad) has its seat on the tonic, on the dominant, and on the subdominant etc.” This is nothing else than what is generally taught, but it does not agree with the content of the essay’s sixth paragraph, which treats of the most natural generation of the most important augmented triad in every key (“die natürlichste Entstehung des einer jeden Tonart wichtigsten übermässigen Dreiklanges”). In the key of C major the triad

A♭ –C–E is declared to be the principal augmented triad. In spite of the author’s best efforts it is barely understandable by what right he can make such a statement, because this chord occurs very less frequently in C major than the augmented triads that arise from the augmented fifths of the tonic’s, dominant’s, and subdominant’s chords. (Reviewer D. 1854, 17, my translation)

[22] A closer look at the Romantic sources reveals a harmonic profile of the Nebenverwandtschaft stronger than that of Weitzmann’s descriptions. Hauptmann’s hypothesis of dualist symmetry between a major tonic and its minor subdominant is inspired by contemporary harmonic clichés such as the altered plagal cadence, the diminished seventh chord, and other formulas involving the flat sixth of the major tonality, and therefore he tries to integrate those various harmonic phenomena into a kind of tonal “theory of everything.” A decidedly subdominant-leaning profile is a substantial thread in the history of nineteenth-century harmony, not the brain-child of Hauptmann’s speculative music philosophy. In trying to merge his systematic approach with the musical and sensual experience of the music of his day, Hauptmann regards the region of the minor subdominant as a counterbalance to the dominant’s region and it provides him an argument for the aesthetic relevance of tonal dualism.

[23] Weitzmann’s comparatively weak echoes of this important school of thought—which was still relevant for Arnold Schoenberg (1922, 270–287)—are too crude either in the description of the augmented triad’s symmetry or, even more troublesome, in his inconsistent labeling of “hard minor” (härteres Moll) as representing normality and “soft major” (weicheres Dur) (Weitzmann 1860, 10) as representing a specialty of Romantic harmony, with the result that he muddles these deeper concepts of Hauptmann’s. These qualities unfortunately limit the influence of Weitzmann’s thought on semitonal movement on the development of neo-Riemannian theories. Whether the loss of dialectic and stylistic information is due to the visionary or the fragmentary character of Weitzmann’s writings is barely relevant because any historical reference to Romantic music theory depends on the intellectual standards as articulated in contemporary publications and reviews, including criticism of Weitzmann’s inadequate way of dealing with the work of both predecessors and contemporaries.

[24] A simple application of the N-transformation in an analysis thus bears the risk of informational loss when N is applied to a basic minor cadence, making the hybrid plagal relation into a simple root progression of a falling fifth and thus the ”inverted” chromatic plagal relation into a simple half-step transformation. Doing so elides the dialectic of the tonic’s tension in relation to its minor subdominant.

[25] The problems described above connected with the N-transformation belong to the larger complex of harmonic phenomena resisting any strictly one-to-one comparison of diatonic fifth-based harmony and the idea of semitonal triadic transformation; these phenomena have to be approached, discussed, and resolved outside of these systematic frameworks. In other words, they call for a creative mix of both harmonic systems. The structures of Lachmann’s mnemonic paradigm may ground a more adequate analytic approach because these give more priority to theoretical models backed by historical tradition than they do to systematic logic. Sharpening the systematic parts of neo-Riemannian theories through a historically informed corrective follows ideas quite similar to the supporting models and constructive criticism of Steven Rings (2007) and Daniel Harrison (2011, 553), both of whom point out the possibility of coexistent systems, or, as Richard Cohn (2012, 171) puts it, of double syntax. Rings’s model of “syntactical interaction,” in particular, seems to have inspired the compromise of Cohn’s “double syntax,” which allows the kind of juxtapositions necessary, although it remains difficult to control the possible interaction of the different paradigms (2012, 171ff, 183ff). This interaction becomes an important feature of analysis in some compositional contexts, as in the case where the structural role of an augmented triad in a tonal modulation driven by that triad’s construction is independent of whether the triad is actually played or not (as shown by Cohn); sometimes the combination of surface-level voice leading and higher-level structure is not a coincidence. For the implications of the Nebenverwandtschaft, thinking in terms of “double syntax” can be an effective approach to describing enharmonic ambiguity and oscillation around the Tonnetz—even within complex tropes like the “double-agent complex” (Cohn 2012, 72–78)—in the whole sensual fullness of harmonic information.

3. Analysis

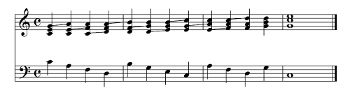

Example 3. Sechter 1835, no. 1, p. 4

(click to enlarge)

[26] Oblique motion from the fifth to the sixth above the bass as an elementary voice-leading model is the starting point of Simon Sechter’s Practische Generalbass-Schule (1835)—see Example 3. Thus we cite Sechter—as we did Fétis in the opening of this article—as a contrasting contemporary witness because of the similarity to transformational theory in his focus on common tones. Here, as earlier, however, we must emphasize that the treatment is founded on entirely different theoretical principles.

Example 4. Sechter 1835, no. 10, p. 12

(click to enlarge)

[27] Sechter’s curriculum in this textbook uses a spiral method of instruction, and when he returns to the opening pattern in the tenth exercise he introduces chromatic elaboration (Auskomposition): see Example 4. In the intervening exercises, a variety of styles appear, from beginner’s tasks reduced to skeletal triadic progressions to standard voice-leading examples and small preludes compiled from the tradition of organ improvisation and partimento patterns. Often those examples where Sechter’s intuitions for didactic progress allow the use of dissonance seem to be more natural and relaxed than the consonant reductions.

3.1. Brahms, “Feldeinsamkeit,” op. 86, no. 2

Example 5. Brahms, op. 86, no. 2, mm. 5–7

(click to enlarge)

[28] Johannes Brahms’s “Feldeinsamkeit,” op. 86, no. 2, implements as a motivic germ the step from the fifth to the sixth scale degree with the augmented fifth as chromatic passing tone—see Example 5. This works as a Schoenbergian “motive of variation,” or guiding idea, for comprehension of the song’s formal design, and the same time its rising motion intensifies the sense of the text (in Example 5 “. . . und sende lange meinen Blick nach oben”: “and for a long while turn my gaze above”).

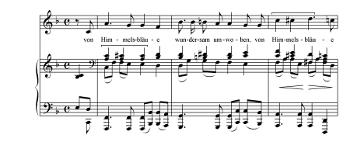

Example 6. Brahms, op. 86, no. 2, mm. 12–17

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

Example 7. Brahms, op. 86, no. 2, mm. 21–23

(click to enlarge)

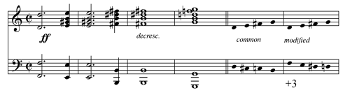

[29] The usual harmonization of a melody involving the augmented triad is the basic motive of the traditional Montesequenz (an ascending +4/−3 sequence; Riepel 1755, 44), which is employed in the following phrase beginning in m. 12—see Example 6 (“von Himmelsbläue wundersam umwoben”: “in wonder enveloped by the heavens’ blue”): bass F–

[30] In this musical narrative of developing variation of the motive C–

3.2. Schubert, Symphony in C major, D. 944, I

[31] As an example of the dynamics of a “Weitzmann region,” Cohn analyzes a passage from the end of the development of Schubert’s C major Symphony, D. 944, first movement—see Example 8. The region around the augmented triad

Example 8. Analysis of Schubert, Symphony in C major, D. 944, I, mm. 304–315, from Cohn 2012, 63 (click to enlarge) | Example 9. Schubert, Symphony in C major, D. 944, I, introduction, mm. 21–24 (click to enlarge) |

[32] The major third relation is already highlighted in the introduction to this movement, starting in a diatonic form—see Example 9. The double counterpoint at the tenth, already predictable in the unison beginning, is a telling feature as it enables the transposition of phrases at the critical interval.

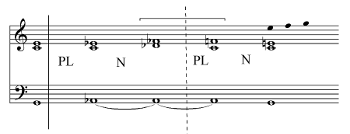

[33] During the modulation returning to the main key, the first chromatic chord progression is heard—see Example 10. This E minor episode anticipates and later grows into a subordinate theme of the subsequent sonata form, where the PL-transformation of the introduction is reintroduced in a compact motivic variant closing a diatonic sequence, the “Parallelismus” (Dahlhaus 1967, 92)—see Example 11.

Example 10. Schubert, Symphony in C major, D. 944, I, introduction, mm. 26–29 (click to enlarge) | Example 11. Schubert, Symphony in C major, D. 944, I, continuation of the second theme, mm. 150–156 (click to enlarge) |

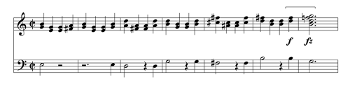

Example 12. Schubert, Symphony in C major, D. 944, I, mm. 200–213

(click to enlarge)

[34] The juxtaposition of a triad against the dominant seventh chord a third below (a iuxtaposition by memory, because the

[35] The “Parallelismus-sequence” went through such a variety of modifications and abstractions in the course of the nineteenth century that merely labeling it or tracing it back to its origins in Renaissance polyphony does not help determine its position in Romantic harmony. It might, nevertheless, be relevant that the pattern’s second chord is often substituted by a chromatically-inflected variant generating a six or six-five chord, a more transitory element. Sechter calls this variant of the sequence the primary form—see Examples 13, 14, and 15. It is of some interest for the technical background of the Schubert passage that Sechter’s compendium shows both variants and that even the chords generated by chromatic inflection are not bound to the original bass line by becoming new root chords—see Example 16.

Example 13. Sechter 1835, no. 15 (click to enlarge) | Example 14. Sechter 1835, no. 67 (click to enlarge) |

Example 15. Sechter 1835, no. 117 (click to enlarge) | Example 16. Sechter 1835, no. 27 (click to enlarge) |

Example 17. Schubert, Symphony in C major, D. 044, I, Parallelismus-sequence (reduction)

(click to enlarge)

[36] In comparing the symmetry of the cited sequence with Sechter’s collection of voice-leading formulas, it is remarkable that Schubert’s voice leading, modeled with uncanny precision and coming dangerously close to “parsimonious voice leading,” nevertheless adheres as closely as possible to the traditional counterpoint of the sequence—see Example 17. In this regard, it is not insignificant that the dominant seventh chords take up the remnants of the six-five chords, and that the suspension chain is essential.(6) We may further note that even the whole-tone scale in the trombone bears traces of a traditional bass figuration.

[37] In employing identical motives, instrumentation, and even pitches throughout all variants, Schubert seems to encourage the listener to cross-fade the diatonic and chromatic alternatives. Because the “Parallelismus-sequence” is in fact derived from the scale rather than from the triad, the dominance of triads played in the modified sequence at the end of the development is the product of the developing variation, whose sensual effect is felt and recognized in the synthesis of both the concrete and the virtual voice leading.

Example 18. Schubert, Symphony in C major, D. 944, I, introduction, mm. 35–38, and voice-leading reduction

(click to enlarge)

[38] The introduction of the symphony presents not only E minor as the upper third relation but also A-flat major, which is reached in the typical manner through a deceptive cadence borrowed from the parallel minor and is left by a singular variant of a Phrygian cadence. Thus, the augmented triad that structures the aforementioned N–R-chain already appears in the tonal layout of the introduction. The harmonies remodeling the Phrygian cadence provoke a breathtaking interaction of virtual and concrete voice-leading—see Example 18.(7) Note that the development of the first chromatic chord progression modifies a common voice-leading pattern by transposing the chromatic counter-voice of the diatonic tetrachord a third upwards. The synthetic harmony over the

Example 19. Schubert, Symphony in C major, D. 944, introduction, mm. 52–61 (click to enlarge) | Example 20. Schubert, Symphony in C major, D. 944, I, introduction, mm. 52–61, voice-leading and transformational reduction (click to enlarge) |

4. Conclusion

[39] It can be useful for analytical work to understand the apparent conflict between traditional diatonic models and chromatic transformations not as a matter of a hypothetical historic development separating the Baroque and Romantic eras but as an essential facet of the aesthetic possibilities available to nineteenth-century composers. In both works analyzed here—the song by Brahms and the symphony by Schubert—tension and form arise via controlled cross-fading of different harmonic levels. By means of harmony, dissonant and transitory events can find stability and evenness when background voice leading is understood as movement through a deeper dimension.

Ariane Jeßulat

Universität der Künste Berlin

ajessulat@aol.com

Works Cited

Cohn, Richard. 2012. Audacious Euphony: Chromaticism and the Triad’s Second Nature. Oxford University Press.

—————. 2000. “Weitzmann’s Regions, My Cycles, and Douthett’s Dancing Cubes.” Music Theory Spectrum 22 (1): 89–103.

Dahlhaus, Carl. 1967. Untersuchungen zur Entstehung der harmonischen Tonalität. Bärenreiter.

Fétis, François-Joseph. 1844. Traité complet de la théorie et de la pratique de l’harmonie. Schlesinger.

Harrison, Daniel. 2011. “Three Short Essays on Neo-Riemannian Theory.” In The Oxford Handbook of Neo-Riemannian Theories, ed. Edward Gollin and Alexander Rehding, 548–577. Oxford University Press.

Hauptmann, Moritz 1853. Die Natur der Harmonik und der Metrik. Zur Theorie der Musik. Breitkopf und Härtel.

Lachmann, Renate. 1993. “Kultursemiotischer Prospekt.” In Memoria. Vergessen und Erinnern (= Poetik und Hermeneutik 15): XVII–XXX. Fink.

Marpurg, Friedrich Wilhelm. 1757. Systematische Einleitung in die Musicalische Setzkunst nach den Lehrsätzen des Herrn Rameau. Johannes Gottlob Immanuel Breitkopf.

Reviewer D. 1854. Review of C.F. Weitzmann’s Der übermässige Dreiklang. Literaturblatt zur Niederrheinische Musik-Zeitung 2 (5): 17–18.

Riepel, Joseph. 1755. Anfangsgründe zur musicalischen Setzkunst. Zweites Capitel: “Grundregeln zur Tonordnung insgemein.” Riepel.

Rings, Steven. 2007. “Perspectives on Tonality and Transformation in Schubert’s Impromptu in Eb, D. 899.” Journal of Schenkerian Studies 2: 33–63.

Schnädelbach, Herbert. 1987. Vernunft und Geschichte. Suhrkamp.

—————. 2007. Vernunft. Reclam.

Schoenberg, Arnold. 1922. Harmonielehre. Third edition. Universal Edition.

Sechter, Simon. 1835. Practische Generalbass-Schule, op. 49. Leuckart.

Spitta, Philipp. 1880. Johann Sebastian Bach. Breitkopf & Härtel.

Sprick, Jan Philipp. 2012. Die Sequenz in der deutschen Musiktheorie um 1900 (= Studien zur Geschichte der Musiktheorie 9). Olms.

Weitzmann, Carl Friedrich. 1853. Der übermässige Dreiklang. Trautwein.

—————. 1860. “Gekrönte Preisschrift: Erklärende Erläuterung und musikalisch theoretische Begründung der durch die neuesten Kunstschöpfungen bewirkten Umgestaltung und Weiterbildung der Harmonik.” Part 2. Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 52 (2): 9–10.

—————. 1861. Die Neue Harmonielehre im Streit mit der alten. Kahnt.

Footnotes

1. Idealist music theory is 19th-century music theory that deals with ideas drawn from idealist philosophy, e.g. Marx, Hauptmann, Riemann, Weitzmann, or even Schoenberg or Sechter. For the interaction of different paradigms see Lachmann 1993, XVIII.

Return to text

2. If the R-transformation is based on the symmetry of the augmented triad—and this is the case—this triad is not falsifiable, i.e. one can neither skip it, nor restore a diatonic version.

Return to text

3. Cohn 2012, 57. “Although Weitzmann’s ordering has transformational implications that we will consider . . . , for him that ordering evidently held no value except as an aid to memory.”

Return to text

4. Weitzmann uses the notion of nebenverwandt to describe other harmonic situations as well. For example: “Ein Ton wird erst durch Nebentöne zum Haupttone, ein Accord erst durch Nebenaccorde zum Hauptaccord. In der Unter- und der Oberquinte wird der Hauptton, die Tonica, seine nächsten Verwandten, seine Dominanten, erkennen“ (1860, 9).

Return to text

5. Here C major-6/4 is a surrogate for G major, modified by suspension; the

Return to text

6. The passing note in the upper voice with the

Return to text

7. Neo-Riemannian transformations often refer to a middle ground level, i.e. they are the result of analytic reduction. It is neither self-evident nor trivial to point out that foreground and middleground are integrated in a synthetic and very special form of the Phrygian cadence: While the flattened sixth degree of C-major,

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2018 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Michael McClimon, Senior Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

9915