The Tristan Chord: Identity and Origin

John Rothgeb

KEYWORDS: harmony, enharmonic equivalence, diminution, Wagner, slide, elision, enlargement, contextuality

ABSTRACT: Theorists have struggled many decades to explain the first simultaneity of the Prelude to Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde. An interpretation that seems to be widely credited today equates the TC with the enharmonically related half-diminished seventh chord. The difficulty with this notion is that the outer-voice interval of the TC is specifically an augmented ninth, not a minor tenth, and these two intervals differ radically in tonal music, not only in function but in sheer sonority. The TC is explained here as resulting from an enlarged slide formation together with a daring application of elision.

Copyright © 1995 Society for Music Theory

[1] One might conclude from the sheer quantity of literature on Wagner’s Prelude to Tristan und Isolde and in particular on the Tristan Chord (TC hereafter) that every conceivable approach to the explanation of that famous sonority had by now been proposed. A sampling of that literature, however, suggests that the identity and origin of the TC is far from settled. Most historical accounts of the chord have been preoccupied by the often irrelevant a- priori assumptions of one or another “system of harmony” and have failed to address the issue from the perspective of composing technique. I will argue that a particular technique of diminution—one well precedented in musical tradition—has been applied by Wagner in a highly original way with results uniquely suited to depict the psychological milieu of the beginning of the opera. To understand the TC fully, however, we must first be clear about its identity—that is, the inventory of intervals it comprises.

The intervals of the TC

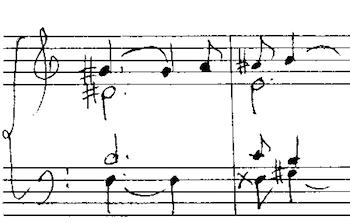

[2] Several recent contributions to the critical and theoretical literature not devoted primarily to Tristan or its chord refer to one or another half-diminished seventh chord as a “Tristan-chord,”(1) while the actual TC as it is presented at the beginning of the opera’s Prelude has on the other hand been called a “half-diminished seventh chord.” Such nomenclature presupposes either that Wagner misspelled the chord on the downbeat of bar 2 of his Prelude or that the language of the music under discussion in the particular case—whether Tristan or another work—makes no distinction between enharmonically equivalent but differently spelled intervals.

[3] The second of these assumptions seems to me obviously

untenable, and I shall not deal further with it here. The

first assumption—that the TC is actually an enharmonic

spelling of a different chord—can, according to Martin

Vogel, be traced back at least to an 1899 account by Salomon

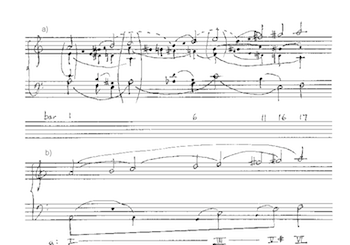

Jadassohn, who represented the bass f as an alternate

spelling of

[4] How can such an assertion of enharmonic spelling be

evaluated? The answer is that it can be evaluated only with

respect to the musical context, and only in the light of a

principle that I will take as axiomatic: the ear will in

general seek simpler explanations over more complex ones,

and, in particular, will posit an enharmonic change only if

compelled to do so by context. For example, the interval 0–4 (in “atonal” notation) is automatically interpreted by the

ear as a major third. An appropriate context can oblige the

ear to hear it as a diminished fourth (in which case it

sounds radically different), but the conditions under which

this will occur are very special ones indeed. Now if we

assume, in the first bar plus upbeat of the Tristan

Prelude, a normal spelling of the first note (A instead of

g-double-sharp), then it is inescapable that the second and

third notes are G and E respectively, since the first

melodic interval will scarcely be heard as an augmented

fifth. (The arguments in support of this contention may,

after the discussion to follow, be supplied by the reader.)

The bass note that enters in bar 2 is at least

enharmonically equivalent, if not identical, to the first

melodic note of bar 1, F. Is it possible that this pitch

has become enharmonically revalued as

[5] Here the ascending continuation of the notated F

strongly suggests its possible interpretation as

[6] Jadassohn’s account of the TC probably does not need to

be refuted for very many modern readers. But the currently

fashionable assimilation of the TC into the category of

“half-diminished seventh” (or vice versa) is really no more

plausible. Since it is established that the bass of this

chord is F, a major third lower than the first note of the

Prelude, the TC can be a half-diminished seventh only if the

oboe’s

[7] The intervals of the TC as measured from the bass up, then, are: A4, A6, A9 (=A2), exactly as notated. Not one of these intervals is present in a half-diminished seventh chord constructed above its root as bass. Only one of them—the A4—is present in any inversion of such a chord.

“Precursors” of the TC

[8] Vogel reports that

In the course of the treatments [described above, by Schoenberg, Hindemith, and Fortner] it was variously noted that the chords could already be found in earlier style-periods. In the quest for precursors it is possible to go back as far as Guillaume de Machaut and Gesualdo da Venosa.. . . In Beethoven’s Piano Sonata inE♭ , Op. 31 No. 3, the Tristan-Chord appears in the same register and at the same pitch. [An example comprising bars 33–36 of the named sonata follow, with an arrow singling out the downbeat chord of bar 36.](4)

[9] If the TC does in fact “appear” in Beethoven’s sonata,

then in what sense is it a “precursor” in that context?

Shouldn’t its name be changed, perhaps to something like

“the Op. 31 No. 3 chord”? The obvious answer is that

Beethoven’s chord—leaving aside the fact that its

correctly notated

[10] The difference, in tonal music, between a minor third and an augmented second is profound. The two intervals fall on opposite sides of the most fundamental dividing line in its language: that between consonance and dissonance. It is hardly surprising, therefore, that they sound very different from one another, as do the TC and the half-diminished-seventh chords.

Compositional origin

[11] Among the many accounts of the

TC that have been proposed in the past, those most nearly

plausible explain the

Note that the phrasing slur for the oboe in bars 2–3 begins on theG♯ 1 under examination and carries through to B1. . . But this is not characteristic of the usual two-tone slur (G♯ 1 to A1) for the indication and execution of an appoggiatura. It should also be observed that the oboe’sG♯ 1 to B1 is accompanied by a very frequent kind of chordal interchange as the bassoon leaps from B toG♯ . . . (6)

[12] It is true that Mitchell’s reference to a “chordal

interchange” begs the question by presupposing that the

[13] Example 2 shows, in four stages, what I propose as the

origin and evolution that led to the TC. (The augmented-sixth chord in the progression at a has, of course, a still

simpler diatonic origin.) The treble in Example 2a takes the

line of least resistance, which is to follow the bass in

parallel tenths and thus to descend a step. If, in a given

application of this basic voice-leading pattern, the

compositional aim is instead to have the treble ascend, then

the tenor may take over the completion of the underlying

descent as in Example 2b. The ascending step in the treble,

however, is “difficult” and requires an expenditure of

effort. It is a deeply rooted musical impulse to provide

some assistance to the treble in negotiating such an

ascending step. One possibility, for example, would be to

apply the technique of “reaching over” (Schenker’s

Uebergreifen), perhaps by letting the upper voice first

leap to C and reach the B thence by descending a step; this

might result in a cadential ![]()

[14] Let us digress for a moment and consider bars 100–108

from Scarlatti’s Sonata K. 461 shown in Example 3a and the

graphic interpretation in Example 3b. The dominant of C

(locally inflected to the minor mode) is reached in bar 102

and extends through bar 107. The extension first repeats

the treble C – B with bass set in parallel tenths; bar 105

appears to initiate a second repetition, but in bar 106 the

treble not only follows the descent of the bass but also

breaks free and ascends to D. (The resulting third-space, B

– D, answers the descending third

[15] Wagner, too, was capable of composing such a slide, and

he did so in bars 2–3 of his Prelude to Tristan. The

tones

[16] The elision, or suppression, of the A1 of bar 2 is

but the first of several such acts that lend the music a

portentously laconic quality. The dominant-seventh chord of

bar 3 “should” continue to an A-minor tonic chord, almost

certainly with C2 in the treble; the bass A would provide

the point of departure for the chromatic passing

[17] This chord requires a contextual explanation different

from that of the two TCs. The bass must enter on C in order

to descend by half-step to its destination, B (the root of V

of V, which now, finally, falls a fifth as expected). The

ascending slide figure in the treble, to be consistent with

the procedure followed thus far, must enter on the same note

as that with which the preceding slide ended—that is, on

d natural rather than the

[18] These observations alone are sufficient to account for the first simultaneity of bar 10. It is certainly possible that the enharmonic equivalence of this chord to the TC and to the half-diminished seventh chord was also a factor in Wagner’s choice of the perfect rather than the augmented fourth at the downbeat of bar 10. After all, it is well known that this enharmonicism is exploited extensively as the opera unfolds. It is possible that authoritative documents (unknown to me) exist which permit inferences about Wagner’s compositional chronology in this matter, but in the absence of such documents I would maintain that considerations such as those I have mentioned in [17] may well have come first and have served as the cradle for the particular enharmonicisms that come to play such an important role later.

[19] These enharmonicisms are of a very special and novel

character. It is well known that the enharmonic equivalence

of different spellings of the diminished-seventh had long

provided an important musical resource. The same is true of

the enharmonic relationship between the dominant-seventh and

the augmented ![]()

![]()

![]()

[20] A voice-leading graph incorporating the elements

described above as elided might appear as in Example 4a (a

simplification of which is given in 4b), where elided

elements are enclosed in parentheses. The relationship of

this graph to the music, however, is perhaps somewhat

different from the normal one of a well-made foreground

sketch to the music it represents: such a sketch should and

does vividly portray the general outline of the finished

composition in such a way as to be immediately recognizable

to anyone who knows the music well. Example 4a as it stands

does not satisfy this criterion. The passage depicted

incorporates modifications so profound that the overall

effect is quite different. Most striking among these is the

suppression of the tonic bass note that “should” appear in

bars 4–5. The result is that the bass arpeggiation of the

tonic triad shown in Example 4 is obliterated in favor of a

prolongation, through bar 16, of the dominant of bar 3.(10) The connection of bar 16 to bar 3 is confirmed by the

reappearance in bars 16–17 of the third-space

[21] The advantages I see in the above explanation of the TC

are that it releases me from the apparent dilemma of having

to interpret the

John Rothgeb

Binghamton University

Department of Music

Binghamton, NY 13902-6000

rothgeb@bingsuns.cc.binghamton.edu

Footnotes

1. For example, Joseph Kerman “Close Readings of the Heard

Kind,” 19th Century Music XVII:3 (1994), 214; Allen

Forte, “Secrets of Melody: Line and Design in the Songs of

Cole Porter,” The Musical Quarterly 77:4 (1993), 623–24.

Return to text

2. Martin Vogel, Der Tristan Akkord und die Krise der

modernen Harmonielehre (Duesseldorf: Gesellschaft zur

Foerderung der systematischen Musikwissenschaft, 1962), 24. Exactly how Jadassohn accounts for the inclusion of

Return to text

3. Vogel, 24.

Return to text

4. “Im Verlauf der Auseinandersetzung wurde verschiedentlich

darauf hingewiesen, dass sich die Akkorde schon im frueheren

Stilepochen finden lassen. Auf der Suche nach Vorlaeufern

kann bis zu Guillaume de Machaut und Gesualdo da Venosa

zurueckgegangen werden.

Return to text

5. “. . . den vom Meister R. Wagner selbst so werth

geschaetzten Theoretiker unserer Kunst.” Hans v. Wolzogen,

Foreword to Carl Mayrberger, Die Harmonik Richard Wagner’s

an den Leitmotiven des Preludes zu “Tristan und Isolde”

erlaeutert (Chemnitz, 1882), 4. Mayrberger’s text was

originally published in Bayreuther Blaetter 4 (1881).

Although Mayrberger’s instinct about the

Return to text

6. William J. Mitchell, “The Tristan Prelude. Techniques

and Structure,” The Music Forum I (1967), 174.

Return to text

7. A formation related to the composed slide is the

appoggiatura from below, when such an appoggiatura is

prepared and the note of preparation is embellished by its

own lower neighbor. These idioms are particularly favored

by Scarlatti. For only two examples, see the Sonata K. 426,

bars 32–33, and the Sonata K. 460, bars 12–13.

Return to text

8. Here I should emphasize that I have cited an example from

Scarlatti not to suggest any historical connection between

the two composers, but merely to illustrate a figure of

diminution—applied, to be sure, in a drastically

different and otherwise unrelated musical context.

Return to text

9. Nevertheless, this chord is much more similar in sonority

to a half-diminished seventh than is the TC. I attribute

this to the initially uncertain identity of the ‘cellos’ ![]()

Return to text

10. In this respect I concur with Mitchell’s reading; see

Mitchell, 170–171 (his Example 4).

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 1995 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Cara Stroud, Editorial Assistant