The Tristan Chord in Historical Context: A Response to John Rothgeb

William Rothstein

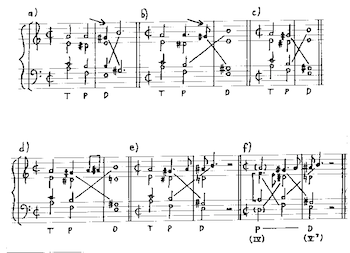

REFERENCE: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.95.1.1/mto.95.1.1.rothgeb.html

KEYWORDS: harmony, recitative, intertextuality, Tannhaeuser, Purcell, Bach

ABSTRACT: John Rothgeb’s analysis of the “Tristan chord” engages a large intertextual network, stretching back to the Baroque and centering on recitative. Examples of a specific figure of recitative, usually associated with the asking of a question, are presented and analyzed. Examples include passages in Wagner's operas before Tristan.

Copyright © 1995 Society for Music Theory

[1] Most of the discussion of Professor Rothgeb’s article so far has

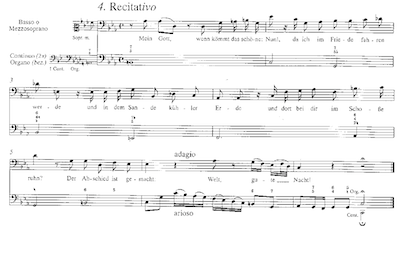

focused, understandably, on enharmonic issues (e.g., can the TC be

legitimately described as a half-diminished seventh chord?). In the

process, it seems, the originality and cogency of Rothgeb’s analysis

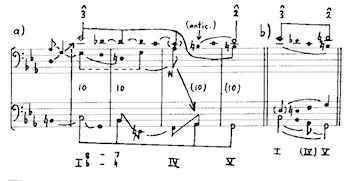

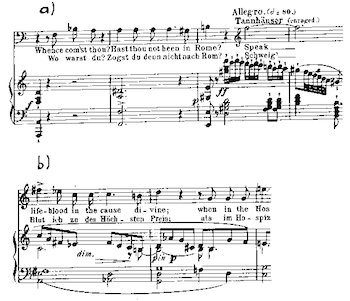

of the TC in its original context—measures 1–3 of the Tristan

Prelude—has gone largely unremarked.(1) When I first read his essay,

I found Rothgeb’s analysis of these measures instantly convincing, and

far superior to the conventional analysis of the TC’s

[2] Rothgeb’s Example 2 isn’t as clear as it might be about the rhythmic

process that, in his analysis, gives rise to the TC. My Example 1

paraphrases his Example 2 in such a way that rhythmic issues are brought

to the fore. Example 1a is essentially the same as his Example 2a, except

that chords are identified by their harmonic functions (T=tonic,

P=pre-dominant, D=dominant), and the reaching-over-cum-voice-exchange

is shown. Example 2b shows a rhythmic shift in the soprano,

anticipating

[3] I have followed Rothgeb’s harmonic analysis thus far, but I don’t

really hear measure 1 as a tonic harmony in A minor. F4 sounds to me like

a consonant chord tone, not an appoggiatura. Along with Deryck Cooke,

I hear the ascending sixth A3–F4, in upbeat-to-downbeat-rhythm, as an

arpeggiation from the fifth to the third of a D-minor triad, which

proves to be IV of A minor(3) the other two ascending sixths, in

measures 5 and 8, are similarly arpeggiations from the fifth of a triad up

to its third. I have added Example 1f to represent this hearing of

measure 1. The bracketed sixth in the example represents the cellos’

ascending sixth. The bass and soprano notes in parentheses are, to my

ear, implied by the larger context; notice the chromaticized voice

exchange between bass and alto. I hear

[4] I now return to Example 1b, which, I here claim, forms part of the pre-history of the TC. Devotees of vocal music will quickly recognize the latter part of this example—everything, that is, but the opening tonic chord—as a common figure in recitative. With its half cadence and its rising melodic gesture, this figure was typically used by composers to set lines of text ending with a question mark. This “question” figure was taken over by Wagner in his early operas; it plays an especially important role in Tannhaueser. The same figure is transformed into the so-called Fate motive in the Ring. I was aware of the “question”/Tannhaeuser/Ring connection before I read Rothgeb’s article, but his analysis of the TC adds Tristan to the intertextual network.

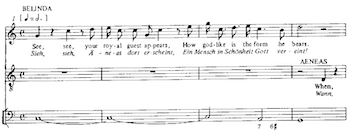

Example 2. Purcell, Dido and Aeneas, Belinda’s announcement of Aeneas’s first entrance

(click to enlarge)

[5] The earliest example of the “question” figure that I am aware of—but almost certainly not the earliest that exists—is the very opposite of a question: it is Belinda’s announcement of Aeneas’s first entrance in Purcell’s Dido and Aeneas (see Example 2). Belinda’s words are “how godlike is the form he bears.” The example is in C major, although the succeeding passage is in G. The figure involves a bass motion from to —here in major instead of the usual minor—with the downward melodic resolution, C5–B4, anticipated in the same way as in Example 1b. D5, at the end of the passage, comes from E5, the third of the tonic triad, which was itself reached by arpeggiation in the first two measures of the recitative. Thus the melodic structure is based on a pair of unfolded thirds: E5–C4 (measures 2–3) is answered by B4–D5 (measures 3–4).

[6] Many examples of the “question” figure, and of figures closely

related to it, occur in the cantatas of J. S. Bach. (Curiously, I

have found no examples in Bach’s Passions.) In each case, the bass

progression is –, usually in minor; often, but not always, the

figure concludes a bass progression descending by step from I to V.

The harmonic progression, naturally, is from pre-dominant to dominant,

with IV6–V the usual choice. The melody, at the half cadence,

features either an ascending leap or an ascending passing motion from

[7] Example 3, from Bach’s Cantata No. 82 (“Ich habe genug”), is

especially striking in connection with Tristan.(4) The middleground harmonic progression, beginning in measure 2, is I–IV–V in C

minor. At the fourth quarter of measure 4 the bass moves from the root of

IV, F2, to its third,

[8] Example 4 is a voice-leading interpretation of Example 3. The passage

is complicated, as one comes to expect of Bach. Level A, a foreground

graph, omits the registral play of the vocal line, which descends into

its lower octave to illustrate the “cool earth” (“kuehler Erde”) into

which the singer longs to be buried. Level B, a middleground layer,

shows more clearly that the passage as a whole is governed by a series

of parallel tenths between the bass and the vocal line; the bass

leads.(5) The last two tenths of the series are displaced by

anticipations and by an unfolding in the bass (shown at level A).

C3—C4 in the graph—is anticipated at the end of measure 3, although it is

sustained by the keyboardist through the first three beats of measure 4.

B3 is anticipated on the fourth beat of measure 4, as indicated above.

While F2 in measure 4 is the root of the IV harmony, the controlling bass

tone within the larger progression is

[9] I do not know whether Wagner took the “question” figure from Bach,

some of whose music he knew very well, or from later composers.

Wherever he got it, he used it in Der fliegende Hollaender (I

haven’t looked for it earlier than that), and especially in

Tannhaeuser.(6) In both operas, the pre-dominant chord used is generally an augmented-sixth

chord of some kind; the minor third from

[10] The figure appears frequently in Act 3, Scene 3 of Tannhaeuser.

While it is not always used to express a literal question, the

figure’s searching quality captures nicely the restless unfulfillment

of Tannhaeuser’s quest. Interestingly, almost all appearances of the

figure in this scene are in either A minor or C major, precisely the

two keys used at the beginning of Tristan. Example 5 shows two of the

figure’s occurrences. The first, in A minor, sets a question from

Wolfram to Tannhaeuser: “Zogst du denn nicht nach Rom? (Didn’t you go

to Rome?)” The second, in C minor/major, is of special interest

because—in the vocal score, at least—it briefly introduces a

transposition of the TC, on the last eighth note of the first measure

(in fact, C4 is sustained by half the violas, so the chord is

literally a French sixth).

[11] The final link in the chain is the Ring. By the time he

composed Tristan, Wagner had completed Das Rheingold and Die

Walkuere, and had composed the first two acts of Siegfried. In

Die Walkuere, the “question” figure appears most notably as the Fate

motive; it also ends the “Todesklage” motive. The two motives are

closely linked in Act 2, Scene 4, the “Todesverkuendigung.” Whereas

all earlier examples of the “question” figure have involved a melodic

leap from

Example 6. Two consecutive occurrences of the Fate motive in the “Todesverkuendigung”

(click to enlarge)

[12] Example 6 shows two consecutive occurrences of the Fate motive in the

“Todesverkuendigung.” As in the Purcell example (Example 2), the text

contains an exclamation, not a question: Siegmund asserts that he will

not follow Bruennhilde to Valhalla (“zu ihnen folg’ ich dir nicht!”).

The passage as a whole is in

[13] I have tried, in this response, to support John Rothgeb’s analysis of the TC indirectly, by drawing a thread back through history. The conceptual evolution of the TC shown in Example 1 mirrors, to a remarkable degree, the historical evolution of the “question” figure, much of which took place within Wagner’s oeuvre. Wagner’s seeming preoccupation with this figure supports the notion that, in the opening measures of Tristan (if nowhere else), ontogeny recapitulates phylogeny. The gradual dissolution of tonal syntax that Tristan did so much to further made continued evolution of this sort extremely problematic. In terms of tonal syntax—harmony and voice leading—Tristan represents a station very near the end of the line.

William Rothstein

Oberlin College

Conservatory of Music

Oberlin, OH 44074

frothstein@ocvaxa.cc.oberlin.edu

Footnotes

1. In this response, I will use “TC” to mean exclusively the first

verticality in measure 2 of the Tristan Prelude. Unlike Rothgeb, I

accept the notion that this chord participates in a network of

collections—all of them reducible, in the abstract, to the collection

[3, 5, 8, 11] and its transpositions—extending over the entire opera.

To my mind, it is this network that ultimately constitutes the

“Tristan chord,” not the specific manifestation in measure 2. However, a

thorough understanding of the language of Tristan requires that each

occurrence of the chord/collection be analyzed independently for its

harmonic, contrapuntal, and (ideally) timbral context. It is the

harmonic/contrapuntal analysis of measures 1–3 that I find most exciting

about Rothgeb’s article.

Return to text

2. A work cited in Allen Forte’s recent response to Rothgeb (MTO 1.2

[1995]), the Harmonielehre of Louis and Thuille, accepts the TC as

an independent augmented-sixth chord, adding it (and two others) to

the inventory of augmented-sixth chords. I thank Daniel Harrison for

bringing this fact to my attention.

Return to text

3. See Deryck Cooke, “The Creative Imagination as Harmony,” in Robert

Bailey, ed., Wagner: Prelude and Transfiguration from Tristan and

Isolde (New York: Norton, 1985), pages 169–76. This essay is excerpted

from Cooke’s The Language of Music (Oxford, 1959).

Return to text

4. Readers who own the Dover volume Bach: Eleven Great Cantatas

(New York, 1976) can find other examples of the “question” figure on

page 61 (measure 4 and measures 8–9 of the tenor recitative “Wie hast du dich,

mein Gott” from Cantata No. 21) and page 157 (measures 7–8 of the tenor

recitative “Der Heiland ist gekommen” from Cantata No. 61).

Return to text

5. On the concept of leading and following linear progressions see

Schenker, Free Composition (Der freie Satz), trans. and ed. by Ernst

Oster (New York: Schirmer Books, 1979), pages 78–80.

Return to text

6. In Der fliegende Hollaender, see Erik’s question “Welch’ hohe

Pflicht?” in his dialogue with Senta.

Return to text

7. Several occurrences of the Fate motive in Die Walkuere explore

still other tonal relationships. See, for example, Bruennhilde’s

question to Siegmund, “So wenig achtest du ewige Wonne?”, in the

“Todesverkuendigung.”

Return to text

8. At the beginning of this scene, where the Fate motive appears at

the same transposition level, A is a suspension. Its tendency to

resolve downward is intensified there by the fact that its

preparation is a dissonant seventh (V7 of E minor).

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 1995 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Cara Stroud, Editorial Assistant