The Silence of the Frames

Richard C. Littlefield

KEYWORDS: aesthetics, analysis, context, semiotics, silence, frame, Cone, Kant, Derrida

ABSTRACT: This essay concerns the edges of musical works, and how those edges are made possible by various frames, especially that of silence. Silence as musical frame is viewed as an index of the more general issue of aesthetic framing. I approach that issue via a reading of Edward Cone's theory of framing silence, as viewed through the aesthetic theories of Immanuel Kant and Jacques Derrida. From that reading I derive a typology of silence as musical frame. That typology is used to effect a reversal of hierarchy in some commonly accepted aesthetic oppositions (such as sound/silence and work/non-work).

Copyright © 1996 Society for Music Theory

1. Introduction

2. Frame and Framing: Kant and Derrida

3. Silence as Musical Frame

4. Conclusion

1. Introduction

[1.1] In the course of deconstructing Kant’s Critique of Pure Judgment, Jacques Derrida questions Kant’s evaluation of the picture frame as mere ornamentation to the art-work proper.(1) Fastening on details that escape Kant’s notice, Derrida ascribes some interesting functions to the frames. Though he does not explore the possibility, it seems to me that these framing functions might apply to musical as well as visual art, and help answer the main question of the present essay, What goes on at the borders of a musical work?(2)

[1.2] The subject of musical borders leads to the more general aesthetic issue of how art is contextualized such that it appears as a “work.” (This last is taken here in its commonly accepted definition, at least since the Renaissance, of an “opus perfectum et absolutum”—a finished man-made product, a self-sufficient entity sui generis that exists beyond the place and time of its creation.) Locating the work is crucial, for in order to get on with analysis, criticism, and the like, one must decide precisely what is work and what is non-work. It seems safe to say that most analyses of musical structure usually proceed as Alice was told to do: they begin at the beginning and go on to the end. This common-sense attitude toward the given-ness of a musical work’s limits, however, is rarely theorized from an aesthetic point of view.(3) Enter the present essay. Here I approach the issue of aesthetic musical context via a typology of the musical frame of silence.

[1.3] Mention of how music is contextualized might lead one to expect a discussion of musical ontology. A massive literature on that topic runs (at least) from Sextus Empiricus’s skeptical dictum that music does not exist—because it must exist in time; but time does not exist, thus neither can music—to modern studies in cognition and psychology—which understand music as primarily a mental construct —to essentialist views of music, which take the art-work as a reification or hypostasis of the composer’s thought, of emotive or psychological processes, of social structures, of “absolute” musical processes, and so on.(4) Such ontic investigations are extremely important, inasmuch as they elucidate the conditions of possibility for anything called “music” to exist; and a thorough study of aesthetic frames would have to make such an excursus. Such transcendental quests, however, lead to questions of the place of music in general knowledge rather than the more limited aesthetic issues that interest me here. Thus any ontological issues touched on here will be done so in passing.

[1.4] Another approach to musical framing is found in analyses of musical closure. For one, Patrick McCreless has theorized different types of closure in tonal music. For another, Naomi Cumming discusses “syntactic frames,” such as phrase and period endings, with regard to their effect on a perceiving subject.(5) These studies, and others like them, shed light on one of the most salient features of musical structure. They do not, however, ask questions about how that structure is taken to be there in the first place, nor how types of framing make musical structures appear as a “work.” Therefore discussion of syntactic framing will not be considered here, though in the “ideal” study of how syntactic and extra-syntactic frames wed, such discussion would be mandatory.

[1.5] In contrast to studies of intramusical framing such as those of closure, much recent writing on musical context stresses the extramusical dimension of things such as socio-cultural, institutional, and pedagogical factors. For example, one recent publication contains an entire section of essays on musical contexts. Among the authors are Charles Hamm (on social contexts of listening that affect musical reception), Peter Rabinowitz (on how verbal texts help cultivate listening habits), John Neubauer (on academic and other institutional contexts of listening), and Ruth Solie (on patriarchy’s use of music to advance its cause).(6) These and other such studies of extramusical context serve as valuable reminders that boundaries between music and non-music are artificial at best; and the writers just mentioned generally understand music to be a phenomenological datum whose borders vary according to who hears it and the competencies those listeners possess. It is not surprising that writers who embrace this antiessentialist view of music tend to eschew detailed structural analysis of the work “itself,” and instead focus on what music does rather than what it is. I accept the logic of this antiessentialist view, but will provisionally accept the idea that something like music exists in and of itself. Not to accept it would end my essay here, since aesthetics arises in response to the notion that (something people call) “beautiful” art exists.

[1.6] Also, possibly relevant to the present essay would be music and writings by John Cage (“There is no such thing as silence”) and Toru Takemitsu (silence as a sign of death).(7) Both of these writers have brought us great insight into Eastern ways of understanding sound, music, and all of life. But because they proceed from such a fundamentally different epistemology than that of the West, to weave their conceptions of silence and music into an essay concerned with European aesthetics would require a much longer format than the present one. Thus Cage’s silence-as-ambient-noise and Takemitsu’s silence-as-death must also await future study.

[1.7] Instead of approaching the subject of silence as aesthetic frame via the possible routes just outlined in paragraphs 1.3–1.6, I shall instead look at Edward Cone’s attempt to answer aesthetic questions about the context of musical art-works in his classic Musical Form and Musical Performance.(8) There Cone advances a theory of silence as musical frame, and my paper picks up where Cone’s leaves off, so to speak. Here I view Cone’s theory through the “lens” of Derrida/Kant, using their writings as a framework or foil by which to (re)read Cone.

[1.8] The remainder of this essay will proceed as follows: First, I shall look at Derrida’s views of aesthetic frames and framing, arrived at in his reading of Kant. Combining Derrida’s views with Kant’s, I derive a set of four self-negating framing functions that characterize and define any and all artistic frames. Second, I use those functions to interpret Cone’s theory of silence-as-musical-frame. In brief, my interpretation effects a reversal of certain oppositions between music/silence, such that the “unprivileged” (rightmost) term is shown to be a condition of possibility for or constitutive of the former. I close with a few comments about how aesthetic frame theory, as interpreted by my reading of Cone, might be useful for analysis and pertinent to the construction of a music aesthetic.

2. Frame and Framing: Kant and Derrida

[2.1] In the section of his Critique of Judgment entitled “Analytic of

the Beautiful” (itself Book I of “The Analytic of Aesthetic

Judgment”), Kant describes the picture frame as a mere ornament

(parergon) to the painting itself. He classifies the frame among

ornaments that do not belong to the internal properties of the work

(ergon) of art, even though such external trappings as picture frames

and draperies or clothes on statues do attach to the work proper. Why

does Kant need to make this distinction? As noted above, in order for

analysis of anything called art to take place—and thus for

aesthetics to be possible—it is crucial to define the proper,

intrinsic object of critical attention. Derrida calls this

determination “a permanent requirement [that] organizes all

philosophical discourses on art

[2.2] Now Derrida suggests that Kant’s exclusion of the frame from evaluations of pure beauty is something of a swindle, because Kant tries to introduce a logical framework that makes it possible to distinguish work from non-work. For this task, Kant borrows categories from his Critique of Pure Reason, and these categories are irrelevant to the discussion at hand—irrelevant because, according to Kant, aesthetics concerns the senses, not the intellect. (We shall return to this problem toward the end of this essay, after watching the same kind of conceptual frame-job bolster Cone’s theory of musical silence.) Derrida goes on to show that the frame can be understood not only as mere ornament, but as that which makes possible the work itself, through action that separates the so-called beautiful form from a general context or milieu. For Derrida, the frame responds to and signifies a lack within the work itself (TIP, 65). This lack makes framing necessary, not just ornamental and contingent, as Kant would have it. In effect, Derrida reverses the hierarchical opposition established by Kant, that of work/non-work. He does so, however, not by establishing a new opposition of non-work/work, but rather by construing the oppositions involved as a set of paradoxes.(9)

[2.3] Four of these paradoxical functions of the frame are listed at the bottom of Figure 1. First, the frame separates the work from its context. In doing so, the frame enshrines an object, thereby bringing it to our attention as beautiful form or “art.” The frame provides us with an object that can have intrinsic content. Second, and at the same time, in any analysis of pure beauty, the frame must not be considered part of the art work, even though physically attached to it. Thus the frame also separates the work from the frame itself. To summarize: in relation to the work, the frame seems to disappear into the general context (such as a museum wall); in relation to the general context, the frame disappears into the work. Therefore the frame belongs fully to neither work nor external context; it has no place of its own. Only framing effects occur, which are not to be confused with the frame itself: “There is framing,” says Derrida, “but the frame does not exist” (TIP, 39).

[2.4] Functions 3 and 4 on Figure 1 are corollaries to this ambiguous ontology. Third: the frame comes to be viewed as contingent, as mere ornament. Fourth: at the same time, the frame must be considered necessary, since it functions to constitute the work. The frame defines the work by confining it. This is a paradox in the rigorous sense; the frame is not contingent or necessary, but both contingent and necessary at one and the same time. It is impossible to decide logically where the borders of the frame stop and the work begins or where the borders of the work stop and the frame begins.

[2.5] Yet as analysts we regularly decide anyway, rarely taking the time to theorize where works “really” begin and end. For a notable exception to this practice, and keeping in mind the four framing functions outlined above, I now turn to Edward Cone’s theory of silence as frame.

3. Silence as Musical Frame

[3.1] In his chapter on the “The Picture and the Frame,” Cone elegantly

rearticulates Kant’s notions of pure beauty, and how the latter must

be separated from things external to itself: “The frame of a picture

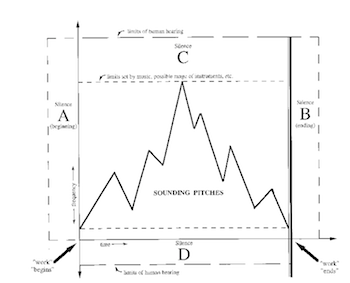

[3.2] To help visualize these frames, Figure 2 gives an oscillograph-like representation of music in action, and shows framing silences that lie at the music’s “edges.” Along the horizontal axis, sounds appear in time; the vertical axis shows the musical highs and lows in terms of pitch space or frequency. Silences A and B represent the horizontal borders of a sounding piece of music, and each has a different function. The beginning silence, A, is that moment in which “nothing should be happening” (MFMP, 16; Cone’s emphasis). It mutely announces: “Here the real world leaves off and the work of art begins; here the work of art ends and the real world takes up again” (MFMP, 15). In a typical concert situation, this silence usually precedes a conductor’s first gesture.

[3.3] Cone’s italicized “nothing,” however, should alert us that

something is going on here. The beginning silence serves as a call

to attention; it focalizes the listener toward what will follow; it

finalizes a milieu. These are of course phenomenological

attributions. And yet that silence is heard, even empirically. The

beginning silence has a propulsive quality, a sense of Doing.(11) It

is modalized, or charged with moods, by the audience’s expectations of

what will follow, even if what follows is unknown to the listener.

Out of this silence the music “officially” begins. This initial

modalization can be affected by the conductor’s first gesture, which

serves as a visual cue that further pre-modalizes the sounds to come.

For example, the “silent” down-beat to the opening of Beethoven’s

Fifth Symphony calls forth high energy in preparation for the urgent

motive that follows. On the other hand, the conductor’s first gesture

can imbue the propulsive beginning silence with a feeling of

relaxation, of Being, as would be appropriate, say, for the pastoral

opening of Sibelius’s Second Symphony. In such cases, Cone

speculates, “perhaps some of the silence [once called the, as in

only, frame by Cone] immediately before

[3.4] We have not yet exhausted the richness in function of the beginning edge of the “silent” frame. Figure 3 shows some possible interpretations of a beginning musical silence. In semiotic terms, if one takes the beginning silence as a sign, it might generate the chain of interpretations shown as an idealized hearing. As a type, it forms an iconic, or similarity, relationship with all the interior silences to follow in the piece. The beginning silence also functions symbolically, since as a call-to-attention it is established by conventions and protocols of concert-going rather than by any inherent property it might have. And on the principle of contiguity, it serves as an index in relation to the music that follows, inasmuch as both sound and silence share the property of duration. Figure 3 also suggests that, at some indefinable point, the beginning silence becomes part of the music itself. The frame has erased itself and yet it was as “there” as any note was. A part of the general context has contaminated or become part of that which is to be understood as self-sufficient, proper only to itself. It is impossible to say exactly where contextual, ambient silence becomes part of the work proper (we have reached one of Cage’s conclusions, but via a different route). Further, the idealized hearing shown in Figure 3 gives only possible interpretations and assumes much that we cannot take for granted, such as our hearing in an “orderly,” or serial, fashion instead of projecting backwards and forwards. And we haven't yet mentioned noise from the general context that might contaminate the frame itself (such as talkers, the crackling of candy wrappers, and so on). In this case another reversal occurs, where, in order to listen with Kant’s/Cone’s ears, we must construe the sound as silence so that the silence we construe as sounding—part of the work proper—can be “heard.”

[3.5] Silence B of Figure 2, the ending border of the music, may be qualified as mainly absorptive, because it captures and dispels the energy of the preceding sounds. This ending silence protects us from the shock of “our return to ordinary time” and should not be intruded on too quickly with applause, lest its function be thwarted (MFMP, 16). The ideal duration of this ending silence will depend on the energy level of the foregoing sounds and their lingering effects on our memory. For example, the silence that frames the end of Debussy’s “Clair de lune” takes little time to dispel the low energy of the preceding music. In contrast, the bombastic chords that end Sibelius’s Fifth Symphony seem to hammer away long after they are gone, and require a lengthy silence to dissipate their force. Silence B can also have a propulsive quality, as silence A, when occurring in multi-movement constructs such as suites, symphonies, and concertos. In these cases and others, silences between movements can also prepare, delimit, or point to what follows. As Cone says, these “moments [of silence] represent frame, like the intermediate frames of a triptych” (MFMP, 17). For instance, the silence after the first movement of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony can be very passive, if one is thinking ahead to the tranquil theme of the second movement. Another example would be the active silence that occurs just after the Introduction to Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring, right before the “Danse des adolescentes” begins. The quality or mood of a silence between movements will also depend on how long the conductor makes the silence. A framing effect might be lost between movements, if the succeeding movement is begun to soon, without enough time in between for the previous music to leave the memory. In that case, does framing occur? Once the new movement is underway, will there be a retrospective imposition of frame? And will that frame be silent? Given all these questions about the silent frames or the framing silences, it begins to seem that, in all rigor, they cannot be classified as mere ornament, as somehow less essential than that which they frame.

[3.6] We have considered beginning and ending silences as frames. Are there other, perhaps internal, frames? Cone does not think so; rather, he construes certain types of non-silences (i.e., sounds) such as preludes and postludes, the “extremes of a composition,” as frames (MFMP, 22). Yet framing silences do not take place only at “beginnings” and “endings” (the scare quotes should need no explanation by now); they also occur, at least potentially, within the music itself. For instance, in the aria “La donna e mobile” from Act 4 of Verdi’s Rigoletto, a fermata appears over one silent measure of rest during the instrumental that follows the first verse (see Example 1). If the conductor makes this rest last long enough, the interior silence might generate the interpretation of a “new beginning.” (An easy way to test this reading is to play the interlude, first giving the fermata a duration of five or six beats, to hear the silence as an interruption; then ten or eleven beats, to hear the pause as a new beginning.) Where emphasized, internal silences tend to be heard as interruptions of continuity, and indeed, almost reverse the accepted hierarchy in the opposition sound/silence. I return to questions of reversed hierarchy at the end of this paper; for now, let’s continue with our typology of frames.

[3.7] Referring again to Figure 2, you will notice bordering silences also in the vertical (registral) dimension. These vertical borders of the frame are mentioned by neither Cone nor Kant. Yet we clearly have at least two ways of construing these kinds of framing silence, which are more empirically silent than silences at either the beginning or the ending: First, silences C and D lie at the limits of human hearing capacity. These borders are normative and what we may call “natural,” because they are determined by physical limitation and the infinite range of possible sound vibrations. (Incidentally, the fact that silences C and D are “natural” would seem to qualify them as inherently beautiful, in Kant’s/Cone’s aesthetics; for the Romantic view included first and foremost among the defining traits of beauty those processes most akin to those found in Nature; hence, the prizing of “organicism” and all that term entails.) Second, the tones of the piece itself can determine vertical borders. The highest and lowest pitches establish borders that confine a piece of music to a certain registral space. Unlike the silence that occurs at the limits of human hearing capacity, the highs and lows produced by the piece itself are constrained by conventions of musical style and genre, and by the physical and mechanical limitations of instruments and/or voices used. In this case, the work itself acknowledges or compensates for its own framing silences, which the highest and lowest pitches “fend off.” Another reversal of function takes place: instead of the imposition of frame from the “outside” (silence, lowered lights, conductor’s gesture, etc.), the framing occurs from the “inside,” by the work itself. The inside does the job of the outside in order for the inside to appear to be framed by the outside—a strange yet necessary illusion if something like a “work of music” is to be said to exist.

[3.8] The “vertical,” or registral, silences (C and D) differ from the “horizontal,” or temporal, silences (A and B). The duration of the work will always be determined by convention, whether the piece is an eight-hour improvisation on an Indian tala or a little Mozart minuet. The horizontal unfolding in time has no “natural” border, as silences C and D have. The beginning and ending silences are not limited by hearing ability and so on, but only by conventions of performance practice and received or earned preference. Thus, while the horizontal silences are contingent, the vertical borders are fixed and necessary, participating in the work, in Kant’s terms, and not serving as mere finery. They are essentially sounding silences, in Cone’s sense, mute to the senses yet essential for the “work” to be heard. Similar to framing silences C and D would be those of “depth”—silences that operate “front to back,” so to speak, and that add a third dimension to Figure 2. Such a framing silence would consist of a front/back or depth relation between listener and work. Where and how these frames of depth operate would depend on physical features of the room or concert hall, the position of the listener in relation to the sound source, and so on. This front/back silence would have a quasi beginning/ending function, on the tree-falling-in-the-forest principle that sound waves start and end when they reach the audial membranes of the inner ear.

[3.9] Other speculation on how depth silence might frame music, as well as on the typology of framing silences, I leave to the reader, assuming he or she has been persuaded that silence is worth consideration. It is time now to look further into Cone’s aesthetic, the place of the frame therein, and the conceptual framework on which his theory rests.

[3.10] For Cone, framing silences give the musical act its own fictional world, despite the fact that that world has nothing to say and nothing to see; as noted before, music has no “internal environment” (representational or propositional content) of its own (MFMP, 16). Yet at least the illusion of such an internal content is necessary for music, as a temporal art, to establish its own, virtual time, in opposition to “ordinary time” (MFMP, 17). In this sense, framing silences of a musical act serve much the same purpose as the “once upon a time” and past-tense cues in narrative. Both establish the borders of a fictional setting in which the story (or music) unfolds. Why, then, if the frame is framing nothing to speak of, or nothing that can be expressed in words or pictures, why then does the music need the frame? To make it seem as if there were something to speak of. Music must provide us with (the illusion of) another, somehow better world, in Cone’s/Kant’s aesthetic, which is the Romantic world of the observer participating vicariously in the creative process of the artist. But this world is not accessible to just any ways of hearing it; rather, it is framed in the mental act of comprehension.

[3.11] One gains access to this other world via two modes of

“comprehension,” which Cone calls the “immediate” and the “synoptic”

(MFMP, 88–89). The former way of listening attunes itself to a

sensible surface, apprehending events as they pass by; the second is a

post-facto understanding of the piece in terms of causality and

syntax. Now, by limiting the ways of hearing to only two, that is, by

framing or setting his argument for music’s need of a frame by

allowing only those two possibilities, Cone sets the context of need—music’s need for a frame—something to make its edges appear:

“

[3.12] It is not as if there were no other ways of listening to music. Pierre Schaeffer, for example, has proffered a third way, which he calls “reduced listening.”(12) This mode of listening focuses on the traits of sound independent of their syntactic function and means of production, and forms a category that would make problematic Cone’s assertion that music has no “internal environment.” For if we concentrate on the sound itself instead of listening immediately or synoptically, we have all the content or internal environment we need. No future or past is necessary since no causality or entailment comes forth upon the discovery (or imposition) of structure by a “synoptic” mode of comprehension. “Reduced listening” has no need of beginnings and endings, and it cannot help us frame the work as heard, at least not a “work” in the sense given it by Cone and Kant and in the sense we are trying to understand here.

[3.13] I mention Cone’s modes of listening not only as a matter of interest nor as a prelude to a phenomenological theory of framing, but rather to recall that a similar imposition of “external” categories prompted Derrida’s questioning of Kant’s aesthetics. As noted in section I of this essay, much of Derrida’s dissertation on the frame concerns Kant’s use of the “outside” framework of reason, which Kant had designated in his Critique of Pure Reason as playing no part in aesthetic judgments, to conceptualize the essentially aconceptual realm of feelings and taste. In Kant’s aesthetics, says Derrida, “a logical frame is transposed and forced in to be imposed on a nonlogical structure” (TIP, 69). A similar move takes place in Cone: he calls in his two modes of listening at the same time as he returns the discussion, near the end of MFMP, to differences between art and non-art (88–96). The chapters in which the discussions of art versus non-art take place in fact frame what is usually understood to be the “content” of the book (a theory of rhythm as the basis of form). Like Kant, Cone is faced with a lack of categories, and must smuggle them in, disguised as mere accessories and ornament. When trying to define the edges of a work of content-less, nonrepresentational, labile and sounding art, Cone relies on the framing metaphor of “outside” structures of content-ed, representational, static and visual painting. He further calls in selected phenomenological categories of listening, in order to frame his own highly persuasive, if ultimately suspect, aesthetics.

[3.14] At the risk of over-summarizing, I won't pursue further the congruences in logic between Cone’s aesthetics and Kant’s, though such a project would likely prove interesting. Instead let me close with a few general observations that seem to follow from the typology of framing silences and from the too-brief analysis just given them. I begin with a look at the treatment of silence in “normal” music analysis, and close with some remarks on framing silence, and on aesthetic frames in general.

4. Conclusion

[4.1] In “normal” music analysis and interpretation, musical silence, like the picture frame, tends to erase itself. In their role as crucial structural determinants—a role which I hope has been successfully argued above—silences rarely figure into systematic accounts of the musical act, just as in the recollection of a novel, criticism usually does not go to spaces between lines, paragraphs, sections, and chapters. This remains the case, despite the fact that many twentieth-century works, such as those by Webern, Feldmann, Crumb, Paert, and others consist mainly of silences that are more salient than those in the various “works” of music mentioned above. Yet criticism and structural analysis usually focus on sounding musical events, leaving silence to be considered incidental, a mere accessory to the work proper. In (the) analysis (business), there is as much silence about the frames as well as of them. And when they are mentioned at all, as in Kant/Cone and Derrida, they receive much more attention than such a mere “accessory” or “hors d'oeuvre” would seem to require. There is a certain urgency, in these writers and in all aesthetics, to give us something with intrinsic content; in Romantic aesthetics, that something is the work itself, pure of essence, and uncontaminated by externals. Perhaps this urgency to peg the frame as accessory, unnecessary, adjunct, and so on comes from a presentiment that, instead of the work itself, the frame should be the proper focus of analysis and criticism.

[4.2] After all, doesn't the frame fulfill all the requirements of Kantian/Conian beauty? For example, it is hard to imagine something more non-signifying, more meaningless than the silent frame. It is less meaningful, in the representational and propositional sense, than absolute music, which has proven itself quite susceptible to verbal description; it is much easier to coax a clear meaning from a piece of sound than from a piece of non-sound. Further, the frame is more a goal unto itself, a better example of Kantian “free beauty” than the work proper, which always needs an “internal environment,” whether that represented world is real (as with the picture) or imagined (as with music). In music, as we have seen, that internal environment is a virtual world of another temporal quality—a world we could not access without the silence(s) of the frames. For a musical work to exist, the frame is necessary, perhaps more so than the “music itself,” which always requires a frame to make itself understood as music. Unlike the work itself, the frame stands alone, inasmuch as it must be understood as adhering permanently neither to itself nor to the work it both serves and makes possible.

[4.3] In conclusion, if all these things are true of the frame, then how might they bear pragmatically upon music analysis? In order to retain the fiction of the autonomous work of music, and all the sophisticated analytic machinery that has been manufactured to show just how “beautiful” that work is, must these functions of the frame—and not just that of silence—be ignored? It would seem impossible to formalize quantitatively the interactions of frame and work. Yet the development of qualitative categories, in a much more detailed manner than has been possible here, might provide or at least suggest new ways of listening. At minimum such a project should construct categories that account for the lack(s) within music that allow us to hear framing as both necessary and contingent at the same time. On the other hand, if all the above things are not true about the frame—if the frame somehow is not as “beautiful” as the music itself, in any of the ways outlined in the previous paragraph—then arguments of how the frame fails to attain “beauty” would interest me very much.

Richard C. Littlefield

Baylor University

School of Music

Waco, TX 76798

richard_littlefield@baylor.edu

Footnotes

1. Jacques Derrida, “Parergon,” a chapter in his The Truth in Painting, trans. Geoff Bennington and Ian McLeod

(Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1987); henceforth called TIP.

References to the Critique of Pure Judgment are to Kant as quoted in

TIP

Return to text

2. This essay is an expanded and revised version of a paper presented at the Summer Congresses of the International Semiotics Institute at

Imatra, Finland, 18 July 1992.

Return to text

3. Here, the term “aesthetic” is intended in its traditional and technical (Romantic) sense of a systematic theory of art, and

especially of art that typifies “the Beautiful” (discussed below).

For a cogent elucidation of the history of aesthetics, from its inception in the mid-1700s to its more utopian construal in the late nineteenth century, see Tzvetan Todorov, Theories of the Symbol (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1982), chap. 6. I discuss elsewhere some of the ideological impact that aesthetics has on musical values, in Richard Littlefield and David Neumeyer, “Rewriting Schenker: Narrative-History-Ideology,” Music Theory Spectrum 14/1 (1992): 38–65.

Return to text

4. Sextus Empiricus, Against the Musicians, trans. Denise Greaves

(Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1986 [2nd century A.D.]). For

a recent gestaltist ontology of music, see Roman Ingarden’s The Work

of Music and the Problem of Its Identity (Berkeley: University of

California Press, 1986). For Ingarden, and for Leonard Meyer before

him, music exists fundamentally in the “communion” between listener

and a concrete sounding object. Ingarden’s study should be taken as

only a recent, and not necessarily representative, example from a vast

literature on music cognition and psychology, which I have neither the

space nor the expertise to deal with here. For an interesting

construal of “art” as a totally subjective mental phenomenon, see

Morse Peckham, Man’s Rage for Chaos: Biology, Behavior, and the Arts

(Philadelphia: Chilton Books, 1965). Essentialist views of music are

manifold; for recent representative examples post-dating the

Pythagorean conception of music as sounding number, see Schenker’s

writings, Edward Cone’s The Composer’s Voice (Berkeley: University

of California Press, 1974); on this issue in literary interpretation,

see E. D. Hirsch Jr., The Aims of Interpretation (Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 1976).

Return to text

5. Patrick McCreless, “The Hermeneutic Sentence and Other Literary

Models for Tonal Closure,” Indiana Theory Review 12 (1991), 35–73;

the author advances a theory of three types of musical closure—syntactic, poetic, and rhetorical—and his article contains a rich

bibliography of other studies on musical closure. Naomi Cumming, “The

Subjectivities of 'Erbarme Dich',” unpublished ms., 1995; excerpts

read at the National Meeting of the Society for Music Theory, New

York, 2 November 1995.

Return to text

6. The mentioned essays are in Steven P. Scher, ed., Music and Text:

Critical Inquiries (Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press,

1992). A more thorough critique of theories of musical context

appears in my review of Music and Text, in Journal of Music Theory

38/2 (1994), 343–53. There exists quite a large body of literature on

discursive framing, in real life and in literature. A recent example

of the latter is Marie-Laure Ryan, “On the Window Structure of

Narrative Discourse,” Semiotica 64/1–2 (1987): 59–81; Ryan construes

narrative according to the metaphor of the computer window as frame

for the fictional world. On the framing of real-life conversations,

see William Labov’s Language in the Inner City: Studies in the Black

English Vernacular (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press,

1972). How insights from verbal discourse studies would play into

theories of aesthetic framing deserves thought, which would of course

far exceed the scope of this article.

Return to text

7. John Cage, Silence (Middleton: Wesleyan University Press, 1961),

51. Toru Takemitsu, Confronting Silence: Selected Writings

(Berkeley: Fallen Leaf Press, 1995).

Return to text

8. Edward T. Cone, Musical Form and Musical Performance (New York: Norton, 1966); henceforth referred to as MFMP.

Return to text

9. Those well-read in Deconstruction will find my usage of Derrida’s

(anti)concepts to be a pale shadow of the originals. Such

domestication (or emasculation) of Derrida’s powerful readings is

commonplace in music studies, and in my view unavoidable, because

beyond their province of Philosophy and the Logos, Derrida’s

“interventions” lose their capacity to instill what some describe as

“vertiginous” effects in the reader, and fail to signify effectively

in Western thought processes and social structures. Furthermore, to

reduce Derrida’s ideas to simple analytic or heuristic “tools” robs

them of their subtle complexity—they simply are not amenable to

summary. On the other hand, Derrida’s readings cannot be overlooked

altogether, given their profound effect on epistemology in all art

studies in the wake of formalism(s). Thus we shall probably see more

taming of Derrida in future, more reduction and transformation of his

thought into “tools” for music analysis. Perhaps the closest thing to

what a Derridean musical deconstruction might look like occurs in some

writings of Lawrence Kramer; see his Music as Cultural Practice,

1800–1900 (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1990), chap. 6;

and his “Musical Narratology: A Theoretical Outline,” Indiana Theory

Review 12/1–2 (1991), 141–62. See also Robert Snarrenberg, “The Play

of 'Differance',” In Theory Only 10/3 (1987), 1–25; and Robert

Samuels' illuminating critique of that essay, in his “Derrida and

Snarrenberg,” In Theory Only 11/1–2 (1989), 45–58; Samuels makes some of

the same points as I do about the desiccation of Derrida, but in a far

more detailed fashion than is possible for me to do here. For a

brilliant de Manian deconstruction of some writings about music, see

Alan Street, “Superior Myths, Dogmatic Allegories: The Resistance to

Musical Unity,” Music Analysis 8/1–2 (1989), 77–123.

Return to text

10. Of course silence is not the only musical frame. As Cone points

out, certain types of introductions and postludes can have framing

effects, as defined by our four functions (MFMP, 23–24). More

abstractly, a composer’s signature can frame a work, by delimiting

audience expectations, establishing ownership, and separating it from

works of other composers. Discourse about music can frame its

reception. When literary genres—for instance, epic (such as

Schenker’s hero “Artist” in his Harmonielehre) and “neutral

reportage”—are used to frame musicological arguments, they can

produce auras of authority and reality, respectively. Also, the

borders of musical works change over time and according to performance

context. For example, a Machaut mass may be framed as a concert

piece, whereas it once served to frame church liturgy. Today it seems

that Satie’s dream of music as furniture has come true. Music, no

longer made to be listened to, serves as a frame that keeps out the

so-called real world. This is evident from the omnipresence of music

as background, in stores, restaurants, markets, and in the popularity

of Walkman headsets. But the issue of musical frames changing over

time is more an issue for cultural semiotics than for the present

discussion.

Return to text

11. The capitalization of certain verbs designates them as technical

terms in “modal logic,” which formalizes the processes of certain

modalities, or subjunctive linguistic moods; such verbs include

Willing, Wanting, Needing, and so on. Eero Tarasti incorporates the

modal logic of semioticians and logicians, such as A. J. Greimas and

Henryk von Wright respectively, and musicologist Charles Seeger in his

theory of musical semiotics. Among other things, Tarasti’s theory

accounts for the interaction of certain modal states either induced or

exemplified by tonal and rhythmic structures. See Tarasti, A Theory

of Musical Semiotics (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995).

On the modalities in general semiotics, see A. J. Greimas and Jacques

Fontanille, The Semiotics of Passions (Minneapolis: University of

Minnesota Press, 1993), esp. 1–43.

Return to text

12. Pierre Schaeffer, Traite des objets musicaux (Paris: Seuil, 1970), 270.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 1996 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Robert Judd, Manager and Tahirih Motazedian, Editorial Assistant