Re: Eytan Agmon on Functional Theory

John Rothgeb

KEYWORDS: harmony, function, scale degree, Riemann, Schenker

ABSTRACT: A recent article by Eytan Agmon proposes a modified version of the theory of harmonic functions promulgated by Hugo Riemann. It is argued here that the proposed theory is superfluous unless the Schenkerian conception of scale degree is trivialized beyond recognition, and that (in any case) the reduction of seven independent scale degrees to only three categories cannot be reconciled with certain palpable musical effects.

Copyright © 1996 Society for Music Theory

[1] Eytan Agmon’s recent article “Functional Harmony Revisited”(1)proposes a theory of functional meaning for harmonic degrees related to that of Hugo Riemann but differing from it by virtue of “greater theoretical rigor and the removal of arbitrary features” (211). As Agmon explains, “the hallmarks of functionalism are: (1) the characterization of individual chords as tonic (T), subdominant (S), or dominant (D) in function; and (2) the notion that the so-called primary triads, I, IV, and V somehow embody the essence of each of these functional categories.” These are the characteristics of functionalism that Agmon wishes to preserve.(2)

[2] Agmon begins by situating functional theory in a larger intellectual context, presenting it as, in effect, a special case of what is known as prototype theory: “Indeed, one way of stating the core idea of the present article is: given a separation of chord progression from harmonic function, the notions function and primary triad are fully reducible to category and prototype, respectively” (199).(3) Note well what is stated here as a “given”: harmonic function is conceived as entirely separable from chord progression. We shall return to this presupposition shortly.

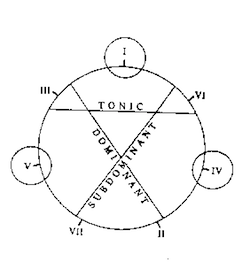

[3] Agmon’s theory is admirable in its simplicity. Its

principal components are (1) a definition, based on

note-content, of degree of triadic similarity for

diatonic

triads; (2) the specification of three “principles” that

“uniquely select the triads I, IV, and V as prototypes of

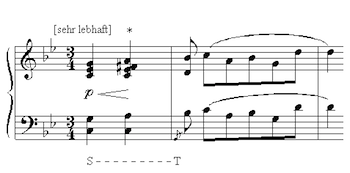

three harmonic categories

Example 1. Agmon’s Figure 2c

(click to enlarge)

Example 2. The final cadence of Schumann’s “Am Kamin” from Kinderszenen

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 3. Graphic interpretation of Schumann’s “Am Kamin” from Kinderszenen

(click to enlarge)

Example 4. The simplified harmonic basis of Schumann’s “Am Kamin” from Kinderszenen

(click to enlarge and listen)

[4] The diagram in Example 1 shows the harmony of II as

standing within the

subdominant function, but also, just slightly, within the

dominant. Agmon puts this into words at a later point in

his essay with the following assertion: “although the

function of II is primarily subdominant, a weak dominant

function nevertheless exists” (206). Does this mean that II

can be both subdominant and dominant at the same time?

Apparently not:

[5] Probably the central core of functional theory (the part that Agmon wishes to retain), unlike many of Riemann’s ideas, was not merely a case of “theory for the sake of theory,” but was rather a well-meaning attempt to respond to problems posed by a wide variety of perceptual phenomena. Let us examine one such phenomenon in detail. Consider the final cadence of Schumann’s “Am Kamin” from Kinderszenen, shown in Example 2. The three-note penultimate chord c–e–a contains the notes of a III in F major, but has the “aura” or in Agmon’s term the “essence” of the dominant; this elusive “aura” is, I suspect, what is sought to be represented by the word “function” in functional theory, most of whose practitioners would here assign the symbol D for dominant. Henceforth in this review I shall (in most cases) enclose in quotation marks any Roman numeral that represents literal pitch content but not “aura,” which latter entity will be designated by Roman numeral without quotation marks. Thus in Schumann’s cadence, the “III” means V.

[6] Why does this “III” mean V? At least two

reasons can be

adduced from the structure of Schumann’s phrase, which is

displayed in Example 3. First, and probably most important, the treble voice

negotiates a fifth-progression (a re-drawing, here in the

coda, of the Urlinie descent). The last passing tone in

that fifth, the g of the penultimate bar, moves to f at the

end; the note a that intervenes, far from obliterating the

g, takes on a subordinate role as a kind of embellishment or

enhancement of the fundamental stepwise progression g–f.

To be exact, it serves as what is variously termed an escape

tone or an incomplete upper neighbor, but is perhaps still

more precisely understood as an anticipation of the third of

the coming tonic harmony. In any case, g implicitly but

effectively remains present as the fifth of c. The third-

space delineated by the succession a–f associates weakly

with the preceding one from

[7] Secondly, an independent force is at work here, one that may as well be called harmonic syntax, or the syntax of scale- degree progression. The simplified harmonic basis of the passage is shown in Example 4a.

[8] We may perhaps agree with functional theory that “the

so-called primary triads, I, IV, and V” are indeed primary

in some meaningful sense. Example 4a is based on the

succession of these primary

harmonies prescribed by the most fundamental principle of

their syntax: that of progression by fifth.(5) (Example 4b

explains the origin of Schumann’s II as the result of

extending the bass of IV and letting the treble anticipate

the fifth of the coming V.) The implication of the first

falling fifth, f–![]()

[9] When I say that in this case “III” means V, the word means may be explicated as “constitutes, or is included within, a harmonic expression of.” “III” may equally well mean I; “II” may mean IV; indeed, instances of “X” meaning Y are legion in the repertoire of tonal music, and virtually no a- priori limits can be set on the ranges of ‘X’ and ‘Y’.(6)

[10] This peculiarity of the relationship of momentary note-

content to harmonic entities was grasped, to a large extent,

by Heinrich Schenker as early as 1906:

[11] Unfortunately, however, this is not what Roman numeral

and

scale degree mean to Agmon. About Brahms’s Intermezzo Op.

117, No. 2, he writes that

[12] The theory of tonal music is thus effectively deprived of the scale degree in Schenker’s visionary conception of it. Once the scale degree has been so devalued to identity with vertical note-content, as it invariably is in Agmon’s article, the inevitable, and completely unacceptable, result is a theoretical void.(10) There is simply no longer any available theoretical correlate for certain palpable musical realities.

Example 5. Agmon’s Example 4a

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 6. Haydn, Piano Sonata Hob. 52, Finale, mm.10–19

(click to enlarge and listen)

[13] In certain contexts, function-theoretic analysis fills this void in a way that is perhaps not objectionable. Agmon’s example 4a is given here as Example 5. It is quoted by Agmon from Aldwell and Schachter’s harmony textbook,(11) with only the replacement of the latter’s (completely sufficient) “IV–I” by “S–T.” In such a case, functional theory could be regarded as relatively benign. There would be no substantive objection to the replacement of the symbols; after all, “IV” and “subdominant” are interchangeable for almost all purposes. For its raison d’etre, however, functional theory would still be indebted only to the trivialization of scale degree and Roman numeral just described.

[14] Functional theory goes much further, though, because it insists that (for example) II always represents one of the primary categories—usually S, less often D (see example 1). How plausible is this claim when it is applied to actual music—for example, to the opening bars of Haydn’s piano sonata Hob. 52, Finale (see Example 6)? The music of bar 1ff. composes out the tonic scale degree, the I. Beginning at the end of bar 8, the same diminution is applied to the second scale degree, the II. Clearly, Haydn has moved up a step. What is to be gained by insisting that the resulting F-minor area stands for anything but scale degree II—by claiming that it represents, for example, the subdominant? The justification for such a claim might argue from the fact that this harmony, like the subdominant so often, moves to V; if so, then all pretense of treating function apart from progression would have to be renounced.(12) In some cases— chiefly when ˆ2 appears in an inner voice, which is hardly the case here—it might be said that II “sounds” (somewhat) like IV (at least to most undergraduate students); this by no means justifies depriving II of its independent place as a harmony in the key.

[15] Worse still, to assert that this II “is” a version of the subdominant would lead to certain bizarre results. It would mean, for example, that the relation between the root of the F-minor harmony in bar 9ff. of example 6 and the root of the initial tonic is primarily to be understood as a fifth rather than a second; and moreover, that the harmonic progression in bars 16–17 is by second rather than by fifth. This is where functional theory ceases to be benign and becomes pernicious.

[16] Thus “II” need not represent IV. It may do so, of course, as has long been understood. In case it does, the explanation is to be sought in domains other than harmonic theory. A careful consideration of such a “II” in its context will show that its constituent scale degree ˆ2has a linear mission (e.g. as a passing or neighboring note).(13)Such a mission excludes any interpretation of ˆ2 as a harmonic root, and thus excludes an interpretation of such a “II” as II.(14)

[17] Agmon had no choice, therefore, but to retract (in at least one instance) his postulate that “harmonic function” can be treated apart from “chord progression.” He represents the case in which he does retract it as special, but in fact the circumstances that lead him to take “chord progression” into consideration there are completely general and equally present everywhere in music. And it is not merely “chord progression” but voice leading, meter and rhythm, motif, and in brief all aspects of what Schenker called Auskomponierung that must be considered in assessing the function—harmonic and otherwise—of chordal entities as they occur in music. Functional theory remains a superfluous appendage so long as we do not discard what has been learned about music thus far.

John Rothgeb

Binghamton University

Department of Music

Binghamton, NY 13902-6000

rothgeb@bingsuns.cc.binghamton.edu

Footnotes

1. Music Theory Spectrum 17/2 (Fall,

1995), 196–214.

Return to text

2. Among the features he is willing to

abandon is Riemann’s notion of Scheinkonsonanz, the

idea that secondary triads are merely “apparent”

consonances, each being accompanied

always, if only tacitly, by an associated “characteristic

dissonance.”

Return to text

3. Later (202), by analogy, “functional

strength” is said to

reduce to “prototypicality.”

Return to text

4. Agmon puts this too strongly in his

statement that

“prototypes must be maximally dissimilar to each

other

Return to text

5. Schenker occasionally speaks evocatively

of the “Quintengeist der

Stufen.” Agmon acknowledges “the privileged status of

certain root relationships, most notably by descending

fifth” (211).

Return to text

6. Certain limits would probably stand up

under scrutiny. Although “II” can, under certain

circumstances, be the sole constituent of an expression of

IV, it is doubtful that “I” and V, for example, could be so

related.

Return to text

7. Heinrich Schenker, Harmony (ed.

O. Jonas, trans. E.M. Borghese; Chicago: University of

Chicago Press, 1954), 139.

Return to text

8. Schachter, “Either/Or,” in H. Siegel,

ed, Schenker Studies (Cambridge: Cambridge University

Press, 1990), 166.

Return to text

9. The identical ![]()

![]()

Return to text

10. Riemann, of course, had to be

completely innocent of

Schenker’s breakthrough, and thus he cannot be accused of

having trivialized an earlier important theoretical insight.

Today matters are different, and it is

discouraging that the best insights in our discipline remain

incompletely understood.

Return to text

11. Edward Aldwell and Carl Schachter,

Harmony and Voice

Leading (second edition, New York: 1989), 392.

Return to text

12. For all that the similar behavior of

II and IV is conventional wisdom, analytic theory and

analytic insight in fact gain nothing by its affirmation,

which is merely a compromise convenient for certain

pedagogical purposes.

Return to text

13. Here I draw attention particularly to

Agmon’s statement,

quoted earlier, that

Return to text

14. It does not, however, exclude the

possibilty that IV may

appear to “turn into” II in the course of prolongation.

Such a reinterpretation exploits the equivocality of the ![]()

![]()

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 1996 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Robert Judd, Manager and Tahirih Motazedian, Editorial Assistant