Beethoven’s Op. 81a and the Psychology of Loss

Eytan Agmon

KEYWORDS: Beethoven, Piano Sonata Op. 81a, program music, psychology, psychoanalysis

ABSTRACT: Two interpretations of the first movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata in E-flat Major, Op. 81a, are offered. According to one interpretation (inspired by Bach’s Capriccio on the Departure of His Beloved Brother), the movement depicts Beethoven’s struggle against Rudolph’s intended departure. According to the second interpretation the movement depicts an internal struggle, and in particular, the vacillation between denial and acceptance characteristic of the psychology of loss.

Copyright © 1996 Society for Music Theory

[1] A curious tendency encountered among the numerous existing commentaries on

Beethoven’s piano sonata in E-flat major, Op. 81a, is to downplay the significance of the

work’s representational trappings. To be sure, Beethoven himself has warned against taking

descriptive titles too literally when he qualified his “Sinfonia caracteristica” as

Mehr Ausdruck der Empfindung als Mahlerei.(1) Yet I doubt that any commentator on Op. 68

has voiced an opinion comparable to Walter Riezler’s, who states that “the

superscriptions

[2] While Riezler represents an admittedly extreme case, his uneasiness with the sonata’s

extra-musical pretensions is shared by other commentators. Wilibald Nagel, for example,

who does not rank Op. 81a among Beethoven’s outstanding masterworks, accounts for its

popularity by referring derogatorily to its descriptive titles. “The outwardly apparent

has the quickest impact on the general public,” Nagel explains, “in general, and

specifically in the arts.”(3)

Even a commentator as Carl Dahlhaus, who never questions the sonata’s artistic merits,

prefers to emphasize its qualities as “absolute” music (its “formal”

aspect), at the expense of its qualities as program music (its “narrative” aspect).

“The sadness at Archduke Rudolph’s departure and the joy at his return,” says

Dahlhaus, “

[3] Why is Op. 81a, Beethoven’s “grosse charakteristische Sonate,”(6) apparently a problem for many

commentators? A number of commentators (though probably not the more recent ones)

have quite possibly formed the erroneous impression that the public display of affection

from one man to another that the work exhibits is inappropriate, if not downright

perverse.(7) However, a less

loaded explanation also exists. As Anton Rubinstein has pointed out, “in the first

movement,

[4] The present essay is an attempt to resolve the problem of musical representation in Beethoven’s Op. 81a by evoking the psychological notion of loss. The notion of loss, and in particular the related idea of an inner struggle between denial and acceptance, makes it possible to view the virile, energetic Allegro of the first movement as representationally wholly appropriate; as a result, there is no need either to question the validity of Beethoven’s inscriptions, or to resort to his famous admonition as a convenient smokescreen. At the same time, sufficiently specific connections between Beethoven’s music and the emotional realm can be drawn to offer a significant alternative to pictorialism. Although much of what follows concerns the sonata’s first movement only, an interpretation of the entire sonata shall be suggested as well.

The Meaning of the Interrupted Lebewohl-Motto

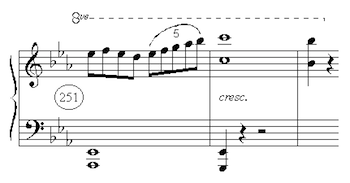

[5] Any representational interpretation of Op. 81a may well begin with the disruption, both textural and harmonic, that the left-hand’s entry in measure 2 inflicts upon the right-hand’s Lebewohl-entity initiated one measure earlier (Example 1). Leonard Meyer believes that “this [deceptive] cadence further defines the ethos of the motto, bringing ‘the eternal note of sadness in’ and perhaps suggesting that the parting is not final.”(9) Indeed, as Meyer subsequently points out, Beethoven’s placing of the horn figure at the beginning of the composition rather than the end, where it more typically belongs, is already deviant.(10) However, I believe there is more to the left- hand’s interference with finality than Meyer suggests.

[6] Several commentators have suggested a possible connection between Beethoven’s Op.

81a and Bach’s “Capriccio on the Departure of His Beloved Brother” (BWV

992), apparently composed when Bach was only nineteen years old on the occasion of his

brother Johann Jacob’s departure to join the retinue of the King of Sweden.(11) Kenneth Drake’s observations are most

illuminating in this regard. Noting that Bach conceived his first movement as depicting the

attempts of the brother’s friends to deter him from embarking on his journey,(12) Drake presents examples from

both Bach and Beethoven where “

[7] In light of Bach’s capriccio, in other words, the first movement of Op. 81a may be interpreted as depicting an external struggle, namely, Beethoven’s struggle against Rudolph’s intended departure. As in the fourth movement of Bach’s work, where the friends realize that the brother’s departure is inevitable and bid farewell, by the end of Beethoven’s movement the struggle against Rudolph’s projected departure subsides, and leave-taking takes place. However, I believe that even greater insight into Beethoven’s work may be gained by applying a variant of the same idea. According to this variant, which I shall pursue through the remainder of this essay, the struggle depicted in the first movement is internal: Beethoven’s subconscious denies what his conscious self already knows, namely, that the Archduke’s departure is imminent. This idea of an inner struggle, however, is more properly introduced through a brief psychological digression.(14)

The Psychology of Loss

[8] From a psychological and psychiatric standpoint, parting from someone we love is a particular case of a more general type of traumatic experience known as “loss.” As Judith Viorst has observed, “we begin life with loss.”(15) More typically, however, loss is associated with such events as the loss of a bodily organ; divorce; and of course, death, be it of a family member, close friend, or a political or spiritual leader.

[9] The psychology of loss probably manifests itself most clearly in the extreme case of

one’s own impending death. In her highly influential book, On Death and Dying,

Elisabeth Kübler-Ross

has proposed that dying patients pass through a progressive

series of more or less pre-determined psychological states that include denial, anger,

bargaining, depression, and acceptance.(16) Although the rigidity of Kübler-Ross’s

five-stage theory has been put to task, the importance of denial as a defense

mechanism in a loss situation has not, so far as I am aware, been challenged.(17) For example, one of

Kübler-Ross’s critics, Edwin Shneidman, asserts that “one does not find a

unidirectional movement through progressive stages so much as an alternation between

acceptance and denial

[10] In interpreting the first movement of Op. 81a as representing the “alternation between acceptance and denial” characteristic of the psychology of loss, it is perhaps significant to note that Archduke Rudolph’s departure is not the only loss that Beethoven has suffered in 1809, either just before or during the period he composed the sonata. On February 19, for example, Beethoven’s physician Johann Adam Schmidt died. The death of Dr. Schmidt, “with whom he developed a strong personal bond,”(19) may have reactivated in Beethoven the trauma connected with one of his most painful losses, namely the loss of his hearing.(20) The suicidal impulses connected with that loss are well documented in the famous “Heiligenstadt testament” of 1802. “Lebt wohl,” writes Beethoven in the testament, and in the postscript he adds: “so nehme ich denn Abschied von dir”; reverberating in Op. 81a, the words “Lebewohl” and “Abschied” thus acquire a particularly poignant quality.(21)

[11] On March 21, Julie von Vering, a woman to which Beethoven seems to have been attracted, died at age nineteen after marrying his friend Stephan von Breuning.(22) This particular loss is perhaps symbolic of a more general one, namely Beethoven’s self-imposed sacrifice of marital happiness for the sake of artistic freedom. Finally, on May 31, Joseph Haydn died. Haydn was possibly a father figure for Beethoven, and thus his death may have carried significant psychological undertones.

[12] Before turning to a more detailed analysis of the first movement, I should like to briefly consider the entire sonata from the present psychological perspective.

[13] Psychoanalysts have noted a connection between loss and creativity. Hanna Segal, for

example, states that “

The Denial-Acceptance Axis: Three Representative Stages

[14] The idea of a struggle between conscious awareness and subconscious denial is incorporated, I believe, into the pianistic fabric of the first movement. The sonata begins with the Lebewohl-motto in the right hand (see again Example 1). Like the word that Beethoven writes above it, the motto is essentially a conventional pattern, the significance of which may be accessed by purely intellectual means.(26) Thus the right hand may be seen as embodying Beethoven’s conscious, rational side, the side that understands (to borrow Shneidman’s phrase) “what is happening.” The left hand—traditionally carrying darker connotations (cf. the Latin sinistra)—assumes under the same interpretation Beethoven’s subconscious, emotional side: it contradicts the right-hand’s realistic stance (in “magical disbelief,” to paraphrase Shneidman again), with its striking entry on the downbeat of measure 2. In other words, the thought of Archduke Rudolph’s departure, while rationally valid (see the right hand), is at this stage emotionally unacceptable (see the left hand).(27)

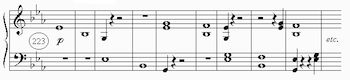

[15] It is most illuminating to turn in this connection to the movement’s ending. In measure 243,

following what may be regarded as the movement’s structural cadence, the left hand begins

a descent in whole-notes from great

[16] Between these two extreme stages of downright denial (measures 1–2, and their

chromatically intensified repetition in measures 7–8) and equally unconditioned acceptance (measures

243–55), several intermediate stages, I believe, may be detected. In the following section I

shall consider the bridge sections (exposition and recapitulation), the development section,

and, of course, the highly important and deservedly celebrated coda. Here I should like to

consider the second subject, which seems to represent a stage lying comfortably near the

middle of our imaginary denial-acceptance axis. To facilitate comparison with the

movement’s beginning and end, I shall consider the second subject as it appears in the

recapitulation, that is, in the home-key of

[17] The second subject consists of two four-measure groups, measures 142–45 and 146–150,

the second of which is essentially a transposition down an octave of the first. In each four-

measure group the Lebewohl-motive is stated twice: in whole-notes at the beginning of the

group, and in quarter-notes near the end (in measure 145 the quarter-note motion G–F is not

followed by an

[18] Weakened resistance to the idea of departure is suggested, I believe, in the disruption

of closure on the downbeat of measure 150: a weakened version of the deceptive cadence of measure 2

(see Example 3a). Indeed, the augmented ![]()

[19] But why, one may ask, is closure disrupted on the downbeat of measure 150, rather than (say) measures 144 or 148, that also conclude a statement of the Lebewohl-motive? The answer, I believe, concerns register. Observe the return to the one-line register in measures 149–50, actually the first time in the Allegro that the motto (upper part only) is heard in its original key and register. Register is an important issue in the movement, given the obvious way in which the motto imitates the sound of two natural horns (thus the Lebewohl-motto, in a strict sense, is register-specific, an idea to which I shall return in connection with the coda). All the same, I am inclined to view the left-hand’s biting, syncopated dissonances accompanying the right-hand’s Lebewohl-motive in measures 142–44 and 146–48 as yet another manifestation of (weakened) resistance to the idea of departure.

The Bridge Sections, Development, and Coda

[20] Generally in this sonata, there is a tendency to avoid sharp formal boundaries, and thus

the traditional categories of first subject, transition, etc., must be applied with some caution.

For example, a large-scale harmonic cycle T–S–D–T overlaps the onset of the Allegro in measure

17, where the sonata’s first subject would seem to begin.(30) Note that measure 21 contains the first stable

tonic chord in the movement, not counting the harmony implicit in measure 1. Since measure 25, also

containing a root-position tonic, merely initiates a varied repetition of measures 21–24, I shall

take measure 21 as the bridge-section’s harmonic point of origin. In what follows I shall propose

that much of the bridge section is based on an enlargement of the Lebewohl-motive G–F–

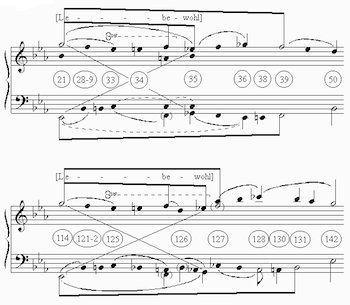

[21] Figure 1 compares measures

21–50 (exposition) with measures 114–42 (recapitulation) at a

background level (there is no Lebewohl-motive at this level). Note that while a soprano

progression, G–F, is common to both passages, the accompanying bass progression is quite

different. In the exposition, the underlying bass motion is of a rising second ![]()

![]()

[22] In Figure 2 lower-level

details are added. Note that in both passages Beethoven composes

a large scale voice-exchange between soprano and bass: G–F–![]()

[23] I find the development section, harmonically one of the most daring Beethoven ever composed, rather enigmatic. Nonetheless, from the rhythmic, textural, and pianistic standpoints the development seems to coalesce around the contrast between long notes (representing the Lebewohl-idea) in the right hand, and a restless “anapest” rhythm, clearly derived from the first subject, in the left hand (measures 73–90; 94–108). I would suggest that this contrast once again represents an inner struggle between acceptance (right hand) and denial (left hand). In measures 98–103, in particular, the anapest rhythm in the left hand is identified with the note C, thus linking the first subject with the left-hand’s entry in measure 2.

Example 4. Measures 181–189

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 5. 197–201, measures 146–150

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 6. Measures 201–204

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 7. Measures 223–231

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 8

(click to enlarge)

[24] Measures 181–97 of the coda (see Example 4) is one of several passages in the movement that employ the Lebewohl-motive in imitation between the hands (in all of these passages the right hand leads while the left hand follows).(31) In the coda, the imitated Lebewohl- motive corresponds rhythmically to the original Lebewohl-motto of measures 1–2 (tonally, however, only the contour of a descending third is preserved). Here, as in the earlier passages, it is significant that the left hand does not contradict the right hand, but to the contrary, confirms its (quasi) Lebewohl-pronunciations through imitation.

[25] The Lebewohl-idea in its original form dominates the remainder of the coda. It is interesting to compare measures 197–201 with the second subject (specifically, measures 146–50), from which they obviously derive (Example 5). Except for register (measures 197–99) or rhythm (measures 200–201), the Lebewohl-idea in the right hand assumes in measures 197–201 its original form (in measures 146–50, by comparison, the sense of a horn-duo is lacking). Note further that unlike measure 150 there is no deceptive ending in measure 201—i.e., no (weakened) denial—and moreover, the left hand in measures 197–99 accompanies with florid counterpoint, rather than syncopated dissonances (cf. measures 146–47), the right-hand’s cantus-firmus-like motto. However, lack of denial is not quite the same as acceptance. When the right and left hands exchange parts beginning in measure 201 (a type of imitative technique), the left hand is “unable” to follow the right-hand’s previous example and leaves the Lebewohl-motto consistently incomplete (Example 6). The entire passage is repeated beginning in measure 209, as if to give the left hand a second chance; this is of no avail, however.(32)

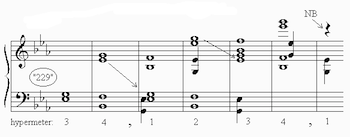

[26] Given the left-hand’s apparent difficulty in “pronouncing” the entire Lebewohl-motto in its original form, a step-by-step, “repeat-after-me” type of learning process follows (measures 223–31). The motto is broken into its component parts, i.e., “second horn” and “first horn”; following the right-hand’s example, the left hand imitates the second-horn part first, and only then attempts, for the first time in the entire movement, the entire motto in two parts (Example 7). Surprisingly, however, precisely as the left hand is finally about to succeed, the right hand enters with a rhythmically distorted version of the motto. The right hand’s entry, initiating the celebrated imitative passage that superimposes tonic and dominant harmonies, does not seem to make much sense in view of the present interpretation. Why should the right hand, which presumably represents Beethoven’s conscious, rational side, interfere with the left hand at this critical juncture, that is, interfere with the process by which Beethoven’s emotional, subconscious side learns to accept the painful reality of Rudolph’s departure?

[27] In answering this difficult question, let me begin with some purely musical considerations. As commentators have not failed to observe, the superimposed harmonies of measures 230–34 result from a logical compositional process by which the durational distance that separates statement (right hand) from imitation (left hand) is shortened from two measures to one. A glance at Example 8—a hypothetical version of measures 229–35—reveals that the motto’s rhythmic distortion serves a number of purposes (in Example 8 the distortion is revoked). First, by shifting the motto’s initial dyad to an unaccented position in the measure the overall dissonant effect is weakened; second, the distortion calls for only two pairs of horns (as opposed to more than two pairs in Example 8), and moreover, preserves the one-to-one correspondence between the horn-pairs and the pianist’s hands; third, the upbeat entry in measure 230 clarifies the hypermeter; and finally, the distortion ensures that the right hand is still heard as the leader, even as the imitative texture becomes considerably more dense.

[28] It is this last point, I believe, that gives us a clue towards solving the question posed earlier. Note that since the right hand states the Lebewohl-motto in its original register in measures 227–29 (see again Example 7), the left hand is forced to imitate one octave lower. But register, we have already noted, is integral to the motto’s identity. The left hand must state the Lebewohl-motto in its original register in order for acceptance to be complete. The right hand’s surprising entry in measure 230 reflects, as it were, this last minute realization: an important ingredient is still missing so as to make the left-hand’s Lebewohl-statement an authentic token of acceptance. Indeed, in measures 232–34 the right hand states the (distorted) motto an octave higher than before; following the right-hand’s lead the left hand makes the corresponding adjustment, thus finally stating the Lebewohl-motto in its “correct” registral position (measures 233–35).

[29] Note the exquisite touch by which the right hand begins yet another Lebewohl- statement, in a still higher register, on the last beat of measure 234. As if suddenly realizing its mistake, the right hand aborts the attempted statement; a rest on the downbeat of measure 235 prevents a dominant/tonic clash similar to measure 231 from taking place. The imitative passage that follows in measures 235–38 (Example 9) serves to confirm, as it were, the state of equilibrium that has been finally achieved within Beethoven’s psyche: both rationally and emotionally, the idea of Rudolph’s departure has been absorbed.(33) Following the brief codetta, measures 243–55, which further confirms that loss has been indeed accepted (review the discussion in paragraph 15), we enter a new psychological phase, mourning, in the second movement.

[30] “Written from the heart,” states Beethoven in the sketches to Op. 81a. Perhaps the present essay should give a new meaning to this simple yet touching phrase. Transcending its immediate, personal context, Op. 81a depicts with uncanny insight the inner workings of the human psyche as it copes with one of the most basic signatures of the human condition: the experience of loss.

Eytan Agmon

Department of Musicology

Bar-Ilan University Ramat-Gan

Israel, 52900

agmone@ashur.cc.biu.ac.il

Footnotes

1. See Gustav Nottebohm, Zweite Beethoveniana (New York:

Johnson Reprint Corporation, 1970; orig. ed. Leipzig, 1887), pages 375 and 378.

Return to text

2. Walter Riezler, Beethoven, trans. G. Pidcock (New York:

Vienna House, 1972; orig. German ed. 1938), pages 81–82.

Return to text

3. “Das Äusserliche wirkt wie überall so ganz

besonders in der Kunst auf die Menge am raschesten ein.” Wilibald Nagel,

Beethoven und seine Klaviersonaten, vol. 2 (Langensalza: Hermann Beyer, 1905),

page 164; see also pages 182–83. W. v. Lenz has also expressed misgivings concerning the

pictorial aspect of Op. 81a. For a valuable summary of various evaluations of the sonata, see

Christoph von Blumröder’s article in Albrecht Riethmüller, Carl Dahlhaus, and

Alexander L. Ringer (eds.), Beethoven: Interpretationen seiner Werke, vol. 1

(Laaber: Laaber Verlag, 1994), pages 626–

28. My thanks to Mr. Ephraim Wagner for his expert linguistic advice with regard to the

translated German passages included in this essay.

Return to text

4. Carl Dahlhaus, Ludwig van Beethoven: Approaches to his

Music, trans. by Mary Whittall (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991), pages 39–40. Carl

Czerny [On the Proper Performance of all Beethoven’s Works for the Piano, ed. by

Paul Badura-Skoda (Vienna: Universal Edition, 1970), page 61] remarks that Op. 81a, “

Return to text

5. See Nagel, page 163; Donald Francis Tovey, A Companion to

Beethoven’s Pianoforte Sonatas (London: Associated Board of the Royal Schools of

Music, 1931), page 189; Prod’homme, page 201; Eric Blom, Beethoven’s Pianoforte Sonatas

Discussed (New York: Da Capo, 1968), page 183; Riethmüller et al., page 627. For a

study of the “storm” movement from Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony that goes

significantly beyond the pictorial surface, see Carl Schachter, “The Triad as Place and

Action,” Music Theory Spectrum 17, pages 158–69. Schachter proposes that

“

Return to text

6. See Beethoven’s letter to Breitkopf & Härtel dated Sept.

23 [1810], in Ludwig van Beethovens sämtliche Briefe, ed. by Emerich

Kastner and Dr. Julius Kapp (Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1975; orig. ed. 1923), page

179.

Return to text

7. Cf. Jacques-Gabriel Prod’homme (Les Sonates pour Piano de

Beethoven, page 202), who suggests (apparently after Charles Malherbe) that Op. 81a may

have been inspired by Beethoven’s love to Therese von Brunswick more than his friendship

to Rudolph. Adolph Bernhard Marx (who was possibly ignorant of the work’s biographical

background) similarly believed that the sonata depicted “moments from the life of a

loving [opposite-sex] couple”; see his Anleitung zum Vortrag Beethovenscher

Klavierwerke, ed. by Eugen Schmitz (Regensburg: Gustav Bosse, ca. 1912; orig. ed.

Berlin, 1863), page 218. While it is doubtful that Beethoven would have made public the

sentiments expressed in Op. 81a had he suspected that these could be interpreted in a

homosexual light, at least from a present-day perspective the work’s homo-erotic

undertones cannot altogether be dismissed. These undertones, however, are totally beside

the point as far as the present interpretation of the sonata is concerned.

Return to text

8. Anton Rubinstein, A Conversation on Music, trans. by Mrs.

John P. Morgan (New York: Da Capo, 1982; orig. English ed. New York, 1892), page 9. As

Uhde has remarked (Beethovens Klaviermusik, page 279), “the fervent activity

that the Allegro displays after this Adagio-‘Introduction’ may have striked a naive observer

as rather strange.” Subsequently in the same paragraph he explains that “in the

entire sonata the contrast between deliberation and determination, between hesitant question

and definite answer, repeats itself again and again.” See also Nagel’s

(Beethoven, pages 167–68) sharp critique of A. B. Marx’s attempt to see the Allegro in

a passionate light. Nagel is evidently disturbed by the Allegro’s apparent programmatic

inappropriateness, for in the same paragraph he rationalizes (cf. Uhde) that

“[Beethoven] never surrendered himself to a painful thought for long, and from the

deepest emotional distress the strength for action arose in him.”

Return to text

9. Explaining Music: Essays and Explorations (Berkeley:

University of California Press, 1973), page 243. Meyer presents a detailed analysis of the first

movement (especially the opening twenty-one measures), and lays considerable emphasis

on the structural implications of the deceptive cadence of measure 2. According to

Blumröder (in Riethmüller et al., Beethoven: Interpretationen, page 630),

the deceptive cadence carries “a specific emotional quality of uncertainty”

(“eine spezifische Empfindungsqualität der Ungewissheit”).

Return to text

10. Ibid., 244. See also Uhde, page 272. Uhde points out that the sonata

as a whole begins with an ending (departure), and ends with a new beginning (reunion), an

idea that he develops into a thesis of contrasting experiences in the time dimension; see pages

272–75.

Return to text

11. Blom, page 182; Richard Rosenberg, Die Klaviersonaten Ludwig

van Beethovens, vol. 2 (Olten: URS Graf-Verlag, 1957), page 325; Uhde, page 279.

However, I am not aware of any documentary evidence from which Beethoven’s familiarity

with Bach’s youthful work may be inferred.

Return to text

12. Bach’s inscription for the first movement is: “Adagio. Ist

eine Schmeichelung der Freunde, um denselben von seiner Reise

abzuhalten.”

Return to text

13. Kenneth Drake, The Beethoven Sonatas and the Creative

Experience (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), page 69.

Return to text

14. I realize that some readers may feel uncomfortable with the idea of

an inner, psychological struggle, and might prefer an interpretation of Op. 81a more on the

lines of Bach’s Capriccio. For such readers, the following section is optional. As for

the remainder of this essay, the terms of an inner struggle (i.e., denying the reality of

Rudolph’s imminent departure) may be easily translated into those of an external struggle

(preventing the Archduke’s departure from taking place).

Return to text

15. Judith Viorst, Necessary Losses (New York: Ballantine

Books, 1986), page 9.

Return to text

16. Elisabeth Kübler-Ross, On Death and Dying

(London: Macmillan, 1969).

Return to text

17. See for example Avery D. Weisman, On Dying and

Denying (New York: Behavioral Publications, 1972), especially chaps. 5 and

6.

Return to text

18. Edwin S. Shneidman, Deaths of Man (New York:

Quadrangle, 1973), page 7.

Return to text

19. Maynard Solomon, Beethoven (New York: Schirmer,

1977), page 114.

Return to text

20. As Solomon notes (loc. cit.), Dr. Schmidt was extremely

helpful in allaying Beethoven’s anxiety concerning the symptoms of deafness.

Return to text

21. In Beethoven’s sketches, (Der) Abschied is the title of the

first movement. See Nottebohm, Zweite Beethoveniana, page 100.

Return to text

22. See Solomon, 154; see also Gerhard von Breuning, Memories

of Beethoven, trans. by Henry Mins and Maynard Solomon, ed. by Maynard Solomon

(Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 38–40.

Return to text

23. Hanna Segal, “A Psychoanalytic Approach to

Aesthetics.” International Journal of Psychoanalysis 33 (1952), page

199.

Return to text

24. George H. Pollock, The Mourning-Liberation Process, vol.

1 (Madison: International Universities Press, 1989), page 114.

Return to text

25. As Maynard Solomon has suggested (Beethoven, page 121),

Beethoven enacted his own death and resurrection in the Heiligenstadt episode. “He

recreated himself in a new guise, self-sufficient and heroic. The testament is a funeral work,

Return to text

26. Uhde (Beethovens Klaviermusik, pages 277–78),

characterizes the Lebewohl-motto as a “Tatsache-Motive”: an unchallengeable,

factual, objective statement.

Return to text

27. In “Auf dem Flusse: Image and Background in a

Schubert Song,” 19th Century Music 6:1 (1982), 47–59, David Lewin

employs a somewhat similar idea of “textural segregation.” See especially Figure

5 and its discussion on pages 56–7. Another point of contact with Lewin’s essay is

psychological. According to Lewin, the poet in Schubert’s setting suppresses a painful

question. Suppression (or repression) and denial are related psychological operations.

Return to text

28. Pointing out that Beethoven’s crescendo in measures 252–53 contradicts the “sigh” implications of the C–

Return to text

29. Concerning the G–![]()

Return to text

30. I read a prolongation of IV from measure 11 (second half) through measure

18. Uhde (Beethovens Klaviermusik, page 282) makes the interesting proposition that

measures 35–50, rather than measures 50–58, are the sonata’s second subject (Uhde considers measures

50–58 as the exposition’s closing group).

Return to text

31. The first passage of this type occurs already near the end of the

exposition (measures 62–65); as several commentators have noted, the passage (restated in the

recapitulation, measures 154–57) makes use of rhythmic diminution. In a broad sense, the idea

of the left hand following the right hand originates from the very beginning of the

movement, where the left hand enters after a full-measure rest.

Return to text

32. Schenker’s implied

Return to text

33. Or, in terms of an external struggle (cf. Bach’s Capriccio),

at this point Beethoven finally allows Rudolph to depart. Interestingly, measures 239–43 are

traditionally interpreted as depicting the withdrawal of the Archduke’s coach.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 1996 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Robert Judd, Manager and Tahirih Motazedian, Editorial Assistant