“Schenkerian-Schoenbergian Analysis” and Hidden Repetition in the Opening Movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op. 10, No. 1

Jack F. Boss

KEYWORDS: motive, hidden repetition, Grundgestalt, musical idea, Schenker, Schoenberg, Beethoven

ABSTRACT: A process akin to Schoenberg’s “musical idea” accounts to a large degree for motivic coherence in the first movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op. 10, No. 1. My article illustrates this process by means of a synthesis of Schenker’s and Schoenberg’s approaches to analysis. I use Schenkerian analysis to identify potential motives at various levels of musical structure, then interpret the treatment of some of these segments according to Schoenberg’s model. I also show how the primary motivic process interacts with other such processes in the first movement.

Copyright © 1999 Society for Music Theory

[1] Among followers of Schenker, the notion of “hidden repetition” has garnered a good deal of interest in recent years. Articles by Beach, Burkhart, Cadwallader and Pastille, Kamien, Rothgeb, and Schachter, among others, have illustrated how repetition of a given motive or motives at different levels contributes to organic coherence in a variety of tonal works.(1) However, one rarely finds in this literature a comprehensive treatment of how the repetitions of a motive (hidden or otherwise) in a piece bind together into one all-encompassing process. Many tonal pieces can be heard as working out just such processes: one not only exists in the first movement of Beethoven’s Sonata Op. 10, No. 1, but also accounts to a large degree for that piece’s motivic coherence.

[2] There is another analytic tradition originating in the same time and place as Schenker’s that concerns itself specifically with the question of how a single process can organize motivic relations (or other kinds of relations) across the surface of a tonal piece. That tradition stems from the theoretical work of Arnold Schoenberg. Schoenberg’s analytic approach has not been adopted as commonly in studies of tonal music as has Schenkerian analysis: one possible reason is a disagreement among scholars who use Schoenberg’s method about its basic terms and concepts, such as “developing variation,” Grundgestalt, and “musical idea.”(2) Accordingly, I begin by briefly outlining my understanding of the Schoenbergian terms crucial to my study. Schoenberg accounts for coherence in a piece by showing how its initial material (what he calls Grundgestalt) sets up an opposition of pitches, chords, motives, or rhythms that is then elaborated through the course of the piece and ultimately resolved (by the principal ingredient of the Grundgestalt absorbing or subsuming its opponent) at or near the end. This blueprint for a whole piece, which can also be thought of as a compositional dialectic, is what Schoenberg means by the term “musical idea” or musikalische Gedanke.(3) My article will show how the motives at foreground and low-middleground levels in the first movement of Beethoven’s Op. 10, No. 1 project a process very much like that described by Schoenberg, but unlike Schoenberg and other scholars who practice Schoenbergian analysis, I will limit what I call “motive” to segments that are equivalent to diminutions in the Schenkerian sense or that combine such diminutions. This is how I plan to forestall the kinds of criticism that have been made against Schoenbergian analysis by Schenkerians such as Rothgeb and Burkhart; namely, that the motivic segments in Schoenberg’s analyses and those of his followers disagree with the segmentation that would be imposed by a correct Schenkerian graph.(4) Since my approach relies on Schenker for motive identification but interprets the relations between some of these motives in a way parallel to Schoenberg’s musical idea, I have given it the label “Schenkerian-Schoenbergian Analysis.”

[3] I believe “Schenkerian-Schoenbergian Analysis” introduces a new way of

amalgamating the two approaches. Others have attempted to combine them, most notably David

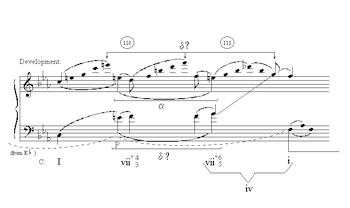

Epstein in Beyond Orpheus, but in ways considerably different from the present

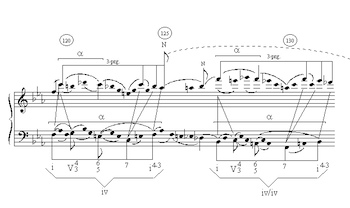

article.(5) Epstein’s concept of

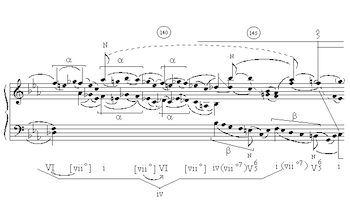

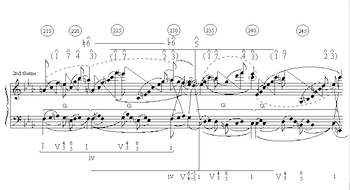

“musical idea” focuses primarily on the power of the Grundgestalt to

unify the piece through its repetition at various structural levels, not on the

dialectical process that organizes such repetitions through the piece.(6) His focus results in some insightful

analyses, which sometimes describe the introduction of elements foreign to the main

tonality within the Grundgestalt and the elaborations through the piece of such

oppositions (his account of the

[4] Another, more recent, contribution that combines aspects of Schoenberg’s theoretical writings with the Schenkerian approach is Janet Schmalfeldt’s Music Analysis article on the “Reconciliation of Schenkerian Concepts with Traditional and Recent Theories of Form.”(7) Schmalfeldt focuses on a different aspect of Schoenberg’s theoretical output from my article: she demonstrates rather convincingly the mutual influences between formal elements introduced or developed by Schoenberg in Fundamentals of Musical Composition and various harmonic-contrapuntal structures characteristic of the Schenkerian viewpoint. Much of her article deals with Schenkerian correlates to the parts of the “sentence” structure proposed by Schoenberg in Fundamentals, but in addition she illustrates how Schoenberg’s distinction between “fixed” themes and “loosely-constructed” themes and transition sections is enriched by and contributes to the Schenkerian perspective. One of the main pieces she analyzes is the same Beethoven sonata movement I take up in my article; accordingly, I will comment on differences between Schmalfeldt’s and my analyses of specific passages in the footnotes.

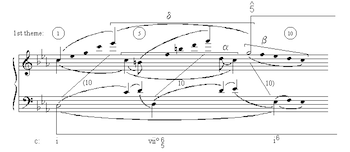

Example 1. Beethoven, Sonata Op. 10, no. 1, i, mm. 1–10, beginning of exposition’s first theme

(click to enlarge)

[5] In Beethoven’s Op. 10, No. 1, first movement, the Grundgestalt is measures 1–9,

the initial period plus the downbeat of the following measure. See Example 1. This opening unit contains two voice-leading strands

within the i - viio![]()

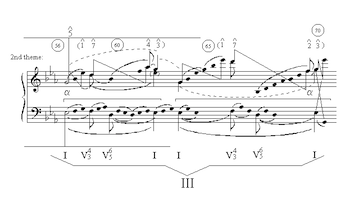

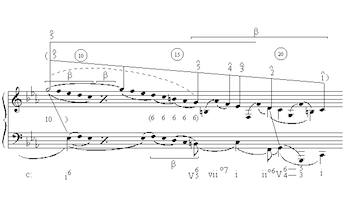

Example 2. Beethoven, Sonata Op. 10, no. 1, i, mm. 56–71, beginning of exposition’s second theme

(click to enlarge)

[6] According to Schoenberg’s “idea,” the next step in Beethoven’s process,

having established an opposition between motives delta and alpha, would be to elaborate

that opposition. Analyses by Schoenberg, Patricia Carpenter, and Severine Neff (as well as

others) illustrate a variety of ways that tonal pieces elaborate such oppositions; often,

one of the opposing elements is a foreign pitch or chord with respect to the home key and

the other is the tonic triad, and the elaboration consists of allowing the foreign element

to simulate a tonic. In the movement under consideration, however, the procedure is a bit

different, since the opposing elements are two motives, both members of the

tonal-prolongational structure of measures 1–9, which are marked as divergent by surface

characteristics such as register and dynamics rather than by the tonalities they

represent. In a few words, Beethoven gradually increases motive alpha’s salience by giving

it delta’s original surface characteristics, while at the same time submerging motive

delta by replacing its dominant characteristics with more recessive ones. This process

then culminates in delta becoming a diminution of alpha, which, it seems to me, makes the

motivic process resemble Hegelian dialectic. The exchange of status between the two

motives begins at the exposition’s second theme, directly following a transition based

almost entirely on the inversion of motive delta. See Example 2.(10) The first presentations of alpha in measures 56–70 are somewhat veiled: they occur in the

middleground behind the bass part, and are inversions of the original alpha. The soprano

during these same measures does not present alpha as such; but instead begins with the

middleground succession ˆ1-ˆ7 ˆ4-ˆ3. This succession not only balances upper and lower

neighbors like alpha and hence can be heard as related to it, but it also creates a rather

normative example of the style structure Robert Gjerdingen identifies as a hallmark of the

Classical era; combined as it is with alpha in the bass and I - ![]()

![]()

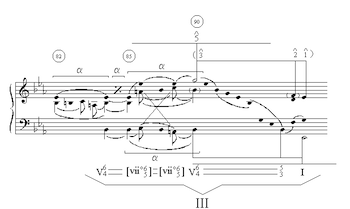

Example 3. Beethoven, Sonata Op. 10, no. 1, i, mm. 82–94, end of exposition’s second theme

(click to enlarge)

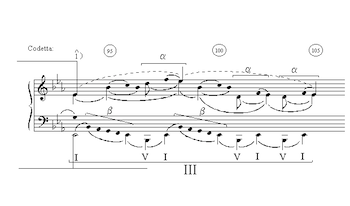

Example 4. Beethoven, Sonata Op. 10, no. 1, i, mm. 94–105, exposition’s codetta

(click to enlarge)

Example 5. Beethoven, Sonata Op. 10, no. 1, i, mm. 106–118, beginning of development

(click to enlarge)

Example 6. Beethoven, Sonata Op. 10, no. 1, i, mm. 118–133, middle of development

(click to enlarge)

Example 7. Beethoven, Sonata Op. 10, no. 1, i, mm. 136–150, later part of development

(click to enlarge)

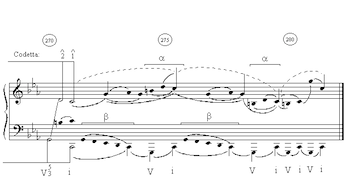

Example 8. Beethoven, Sonata Op. 10, no. 1, i, mm. 215–248, recapitulation’s second theme

(click to enlarge)

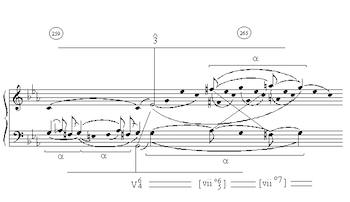

Example 9. Beethoven, Sonata Op. 10, no. 1, i, mm. 259–267, latter part of recapitulation’s second theme

(click to enlarge)

[7] The principal way that Beethoven increases motive alpha’s salience in this movement is to bring it from the middleground closer to the surface (and then he gives it delta’s surface characteristics, as I suggested above). Authors on hidden repetition generally refer to this technique as “contraction”; see for example the Rothgeb and Burkhart articles mentioned in footnote 1. There are three contractions of alpha in the second theme’s closing measures—one at measures 82–84 (which is repeated at measures 84–86) and the others at measures 86–90, in the alto and bass. See Example 3. Beethoven highlights the first contraction of alpha as a segment by repeating it, while the second and third at measures 86–90 are set off by registral and textural changes, as

well as by the reintroduction of the ascending arpeggio prefix characteristic of delta

when it first appeared in measures 1–9. These three double neighbors are not literally on the

surface of the music, but are certainly closer than their counterparts in measures 56–70

(actually, not being on the surface helps us hear them as increasingly salient, given the

fast tempos at which the passage is normally played). The last two alphas at measures 86–90

incorporate a

[8] The codetta in the exposition summarizes the direction of the foregoing measures

and at the same time brings alpha forward all the way to the surface of the music. See Example 4. The tonic pitches in the descending

[9] The development section begins with a presentation of motive delta, the ascending

third, in C major, which retains many of the surface features that accompanied delta in

the first theme: the ascending arpeggios leading up to ![]()

![]()

![]()

[10] The trend of bringing motive alpha forward to the surface and thus increasing its

salience, which we heard in the exposition, continues in the development. See Example 6. At measures 119–21, we hear the double

neighbor at the surface in the soprano: this is the original form, with lower neighbor

first. It appears again a perfect fourth higher at measures 127–29, as part of a sequence

tonicizing first iv, then iv of iv. At the same time, the inversion of alpha underlies the

tonicizations of F minor and ![]()

![]()

[11] As one would expect, the recapitulation replays the motivic process we heard in

the exposition, with few changes (although one of those changes is extremely significant

to the motivic process as a whole). Motive delta reasserts itself at measures 168–76,

“pushing alpha back down into the inner voice,” as it were. And although the

recap’s transition points toward F major rather than

[12] In measures 251–53, the movement’s fundamental line makes its descent to ˆ3, and this is followed almost immediately (at measures 259–67) by the statements of motive alpha that we heard first in the latter measures of the exposition’s second theme. See Example 9. In the recap, the double neighbors ornament the fifth scale degree, G, setting the listener up for the movement’s final cadence. The first two of these at measures 259 and 261 are not that different from their counterparts in measures 82 and 84. (One might comment on the way the upper neighbor is delayed in the second alpha through consonant skip diminutions.) But the third and fourth manifestations of motive alpha at measures 263–67 add something significant to their counterparts at measures 86–90: the double neighbor that mirrors that of the bass has been moved up from the alto into the soprano. As the alto had earlier, the soprano here projects a transposition of the original alpha motive (that is, with lower neighbor first). Like its alto predecessor, this soprano occurrence of alpha includes an ascending third as a diminution between the lower and upper neighbors, and the ascending third, like the original delta of measures 1–9, is ornamented by arpeggios. This subsumption of delta and its diminutions by alpha, as I suggested before, constitutes the motivic synthesis that completes the movement’s overarching dialectic. While this synthesis had been buried in an inner voice at measures 86–90 (like the alpha motive itself at measures 1–9), here it bursts into prominence, capturing both of the outer voices that had belonged to delta at the beginning of the movement.

[13] Thus the surface, foreground, and low middleground manifestations of motives alpha

and delta project a process akin to Schoenberg’s musical idea, which gives a kind of

motivic coherence to Beethoven’s work that goes beyond simple unity. One question remains

to be answered, however, concerning my account of this motivic process, a question that

may have caused some skepticism on the part of the reader. Namely, to what extent can we

think of entities such as alpha and delta as motives, since many tonal pieces

depend on and often feature double neighbors and ascending thirds harmonized in parallel

tenths? Shouldn’t these rather be thought of as common voice-leading components of the

tonal system? David Epstein in Beyond Orpheus suggests one answer to this question;

I will consider his and then contrast it with my own. According to Epstein, a common tonal

element such as a major triad can be heard as a motive if it displays some “unusual

property or characteristic” that it shares with other manifestations of that motive

in the piece. For example, his attribution of motive status to the two

[14] In the opening movement of the Op. 10, No. 1 sonata, however, it is difficult to find unusual characteristics of (for instance) the alpha motive in measures 1–9 that it shares with the other manifestations of alpha in the piece. Indeed, alpha’s gradually taking on new characteristics as the movement progresses is a crucial reason for my hearing the piece as the elaboration of an opposition between alpha and delta. It seems that here the motives should be justified as such on different grounds. Possibly the fact that they take part in a process that spans the entire piece is enough; in other words, it is the motivic progression itself that invests alpha and delta with motivic significance. My viewpoint here does not go too far beyond Schoenberg’s when he asserts in Fundamentals of Musical Composition that “every element or feature of a motive must be considered to be a motive if it is treated as such, that is if it is repeated with or without variation.”(14) The main difference is I am claiming that it is not mere directionless repetition or variation, but an organized process of repetition and variation that causes me to single alpha and delta out from among all the other components of voice-leading in the piece. Many tonal pieces do indeed repeat and vary double neighbors and third-spans harmonized in tenths, but how many set two such components against one another in an opposition based on surface characteristics at the beginning, allow one to gradually wrest the position of dominance (or salience) from the other as the piece progresses, then culminate the process at the end by making the component that had been more salient at the beginning serve as the diminution of the other?

Example 10. Beethoven, Sonata Op. 10, no. 1, i, mm. 9–22, latter part of exposition’s first theme

(click to enlarge)

Example 11. Beethoven, Sonata Op. 10, no. 1, i, mm. 270–284, recapitulation’s codetta

(click to enlarge)

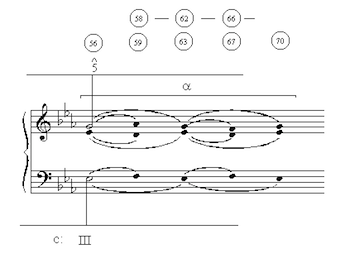

Example 12. Beethoven, Sonata Op. 10, no. 1, i, mm. 56–71, reduction showing the underlying voice-leading

(click to enlarge)

[15] One other voice-leading component that Beethoven identifies as a motive through

the process in which it plays a part is what I will call motive beta. Motive beta gives

rise to a non-dialectical process that also helps to structure the work, and in addition

beta combines with delta and alpha in ways significant to the shaping of the piece. Motive

beta is the stepwise descent through a perfect or diminished fifth. Its most common

version, G-F-

[16] Another aspect of the piece’s motivic structure that my account of the dialectic

involving delta and alpha ignored is the occurrences of these two motives at levels higher

than the low middleground. There are a number of them, but we will focus on only one,

portrayed in Example 12. This example

verticalizes the unfoldings from the second theme in the exposition and changes some

registers to clearly illustrate the underlying voice-leading. As it turns out, the

unfoldings in measures 56–70 project an upper neighbor G-

[17] We have seen that a segmentation of Beethoven’s Op. 10, No. 1 according to Schenkerian principles reveals a succession of motives that closely resembles the compositional dialectic of Schoenberg’s “musical idea.” I believe that this approach constitutes a new way of combining Schenkerian and Schoenbergian analysis, one that could have value for the analysis of works other than Beethoven’s. Recently I have tried a similar “hybrid” approach for the analysis of the first movement of Mahler’s Tenth Symphony and for some of Schoenberg’s Op. 6 songs. With both composers, “Schenkerian-Schoenbergian Analysis” led to some significant insights about how the music makes sense as a process in time. What is most interesting is that Schoenberg’s “idea” is able to form a framework for pitch structures in Beethoven and Mahler as well as Schoenberg’s own music—possibly this musikalische Gedanke could be one among several keys to understanding the development of music in German-speaking countries in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries.

Jack F. Boss

School of Music

1225 University of Oregon

Eugene, OR 97043-1225

jfboss@oregon.uoregon.edu

Footnotes

1. David Beach, “Motive and Structure in Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op. 110,

Part I: The First Movement,” Integral 1 (1987): 1–29; Charles Burkhart,

“Schenker’s Motivic Parallelisms,” Journal of Music Theory 22 (1978):

145–75; Allen Cadwallader and William Pastille, “Schenker’s High-Level Motives,”

Journal of Music Theory 36 (1992): 119–48; Roger Kamien, “Aspects of Motivic

Elaboration in the Opening Movement of Haydn’s Piano Sonata in

Return to text

2. For instance, David Epstein’s Beyond Orpheus: Studies in

Musical Structure (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1979), in general treats the Grundgestalt

as a unifying interval pattern, while Patricia Carpenter and Severine Neff (and I)

understand it as the source of a “tonal problem” that gives rise to a process of

elaboration and resolution. See the Carpenter and Neff articles cited in footnote 3.

Return to text

3. Schoenberg mentions musical idea and its components briefly in

essays such as “New Music, Outmoded Music, Style and Idea,” Style and Idea,

trans. Leo Black, ed. Leonard Stein (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984), pages

113–24, and in Fundamentals of Musical Composition, 2nd ed., ed. Gerald Strang and

Leonard Stein (London: Faber and Faber, 1970). He treats the concept more substantively in

his posthumously-published textbook The Musical Idea and the Logic, Technique and Art

of its Presentation, ed., trans., and with a commentary by Patricia Carpenter and

Severine Neff (New York: Columbia University Press, 1995), though even there he does not

present a complete illustration of a musical idea manifested by an individual work. More

exhaustive applications of Schoenberg’s approach are provided by his student Patricia

Carpenter and Carpenter’s student Severine Neff in a series of articles, of which the

following are representative: Carpenter, “Grundgestalt as Tonal

Function,” Music Theory Spectrum 5 (1983): 15–38; idem, “A Problem in

Organic Form: Schoenberg’s Tonal Body,” Theory and Practice 13 (1988): 31–63;

Neff, “Schoenberg and Goethe: Organicism and Analysis,” in Music Theory and

the Exploration of the Past, ed. David Bernstein and Christopher Hatch (Chicago:

University of Chicago Press, 1993), pages 409–33.

Return to text

4. John Rothgeb, review of Brahms and the Principle of Developing

Variation by Walter Frisch, Music Theory Spectrum 9 (1987): 204–15; idem,

“Thematic Content,” 40–42; Charles Burkhart, “Schenker’s Motivic

Parallelisms,” 146–47.

Return to text

5. See footnote 2 for a full reference to Epstein’s work.

Return to text

6. Such an interpretation of Schoenberg’s concept can be traced back

to Josef Rufer’s analysis of the first movement of Beethoven’s Sonata Op. 10 No. 1 in Composition

with Twelve Notes Related Only to One Another, trans. Humphrey Searle (New York:

Macmillan, 1954), pages 38–45. Rufer highlights the repetitions and variations of motives in

the movement’s initial phrase, showing how such techniques unify the movement (and mark

Beethoven as a precursor to Schoenberg the twelve-tone composer), but gives no suggestion

that a process involving problem, elaboration and resolution organizes the motivic

variation.

Return to text

7. Janet Schmalfeldt, “Towards a Reconciliation of Schenkerian

Concepts with Traditional and Recent Theories of Form,” Music Analysis 10/3

(1991): 233–87.

Return to text

8. Example 1 also

illustrates the initial occurrence of a third motive, beta, the descending fifth. Its

later manifestations in the movement will be discussed at length in paragraph [15].

Return to text

9. My reading of measures 1–9 is modeled (though not at every point) on Schenker’s analysis in “Further Consideration of the Urlinie: I,” trans. John Rothgeb, in The Masterwork in Music, vol. 1, ed. William Drabkin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1994), pages 105–06. Schenker’s graphs at levels d) and c) in this analysis not only clearly portray what I am calling motive delta as an ascending third harmonized in tenths and my alpha as a neighbor C5-B4-C5 that is then turned into a double neighbor through the addition of the diminution D5, but they also give alpha a smaller notehead size, marking it as an inner voice in this initial presentation. Schenker in the commentary writes about a “dispute” between alpha and delta, characterizing them as ‘competitors’ for status as principal line and asserting that delta deserves preeminence as initial ascent to the primary tone.

The characterization of the two motives in this Grundgestalt as opponents actually did not originate with Schenker. He may have been aware that Anton Schindler, Beethoven’s contemporary and associate, described this same passage as a manifestation of the concept of Zwei Principe, which in Beethoven’s thinking (according to Schindler) involved the opposition of ‘strong’ and ‘gentle’ musical characters. See Nancy Hager, “The First Movements of Mozart’s Sonata, K. 457 and Beethoven’s Opus 10, No. 1: a C Minor Connection?,” The Music Review 47/2 (1986–87): 95–96.

Janet Schmalfeldt in the above-mentioned Music Analysis article (page 256, first

half of Example 8) also presents a graph of measures

1–9, which differs only in one essential aspect from my reading: she does not interpret

the D5 in measure 8 as part of a double neighbor figure, but as a chord tone harmonizing the

middle member of the lower neighbor C-B-C. My reasons for highlighting the D5 as part of

motive alpha will become obvious; but her reading has the advantage of more faithfully

following Schenker.

Return to text

10. The transition is not shown in Example 2 to save space in the graphical file; the reader will want to refer to the full score for measures 32–56. Descending groups of three parallel 10ths can be heard at measures 34–36 and measures 38–40; while measures 42–46 adds tenths before and after to extend the motive to five parallel tenths, and the dominant pedal following measure 48 repeats the descending form of delta twice at measures 49–52 and 53–56, in soprano and tenor voices.

Schmalfeldt also provides a graph of the second theme in her Ex. 14 (pages 272–73). The

reader can compare her analysis with both of my Examples

2 and 3 (Ex. 3 will be discussed in the

following paragraph). Again, the general perspective—second theme as a prolongation of ˆ5

over III, a focus on neighbor motion in measures 56–71 and a middleground descent in measures

90–94—seems to be the same. But we differ on some of the details, especially our readings

of measures 82–86. Schmalfeldt hears this passage as a prolongation of ˆ6 over IV (the

Return to text

11. Robert O. Gjerdingen, A Classic Turn of Phrase

(Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1988), especially chapters 4 and 5.

Return to text

12. My interpretation of measures 86–90 as two alpha motives hinges on

reading the six-four chord in measure 88 as a passing chord within a prolongation of the same chord

from measure 86 to measure 90. This sort of interpretation has precedents in the Schenkerian

literature—for example, Schenker’s own reading of measures 21–28 of J. S. Bach’s C-Minor

Prelude from Book I of the Well-Tempered Clavier. Schenker maintains that a cadential six-four chord in measures 21–27 resolves to ![]()

Return to text

13. Epstein, Beyond Orpheus, pages 127–29.

Return to text

14. Schoenberg, Fundamentals of Musical Composition, page 9.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 1999 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Jon Koriagin and Rebecca Flore and Tahirih Motazedian, Editorial Assistants