Towards a Typology of Minimalist Tropes

Rebecca Leydon

KEYWORDS: subjectivity, minimalism, syntax, musematic repetition, discursive repetition, hierarchy, Naomi Cumming, Richard Middleton, Michael Nyman, Arvo Pärt, Raymond Scott, Spring Heel Jack, John Oswald, Frederic Rzewski

ABSTRACT: While minimalism as a style is characterized by the monolithic technique of “musematic” repetition, the style is, at the same time, capable of projecting a broad range of differentiated affects. Building on the work of Naomi Cumming and Richard Middleton, this paper develops a preliminary typology of “musematic” tropes, based on the intended and experiential effects of ostinato techniques. One particular trope, which I term the “aphasic,” is explored with references to Michael Nyman’s The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat.

Copyright © 2002 Society for Music Theory

[1] In most accounts of musical subjectivity, much depends upon the workings of musical syntax, the linear trajectory through which a subject is drawn as a piece of music unfolds. In this paper I am interested in what happens when this type of linear trajectory is absent. More specifically, I am wondering what kinds of subjectivities are possible when musical syntax is undermined by obstinate motivic repetition. Repetition can potentially serve a great variety of expressive purposes: the transcendent mysticism of John Adams’ Shaker Loops, the prison-house effect of Frederic Rzewski’s Coming Together, and the cool indifferent mechanics of Michael Nyman’s Musique a grande vitesse all rely upon the monolithic technique of incessant motivic repetition. How are such varied expressive effects achieved when musical syntax plays such a limited role?

[2] To begin to address these questions, I will first consider some recent accounts of musical subjectivity and the role that syntax plays in these models. Much of the work of the late Naomi Cumming deals with what she calls “the musical subject.” In her published analyses of Steve Reich’s Different Trains and of J. S. Bach’s “Erbarme Dich” from the St. Matthew Passion, Cumming focuses upon the ways in which these works construct musical personae that serve as figures of identification for the listener.(1) As she describes it, this “musical subject” is what listeners become while they are engaged with a piece of music.

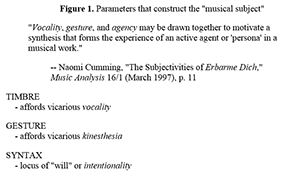

[3] Cumming argues that the sense of this musical subject emerges from the interaction of three parameters, as summarized in Figure 1. The first is timbre, which involves the listener in a kind of vicarious vocality: the human voice serves as an interpretant for the grain of the musical sound (as in the “plaintive” tone of an oboe, “screaming” guitars, or “muffled” horns). The second is gesture, through which a listener gains access to a vicarious kinesthesia: physical gestures of the body serve as interpretants for motivic shapes, rhythms and contours (as in a “soaring” melody, “creeping chromaticism”, or a “power chord”). Third, syntax can serve as the locus of causality and intentionality: the elements in music which create implicative expectanciesvoice-leading, harmonic progressions, conventionalized forms and generative grammarsthese elements draw us through a linear trajectory that can be understood as “causal” in some sense.

[4] Drawing on David Lidov’s ideas on “Mind and body in music,”(2) Cumming links the “bodily” subject primarily with the domains of timbre and gesture, while the domain of syntax is more closely connected with “the will” or the volitional agency of the musical subject. It is the three parameters of timbre, gesture, and syntax, taken together, which produce the sense of the “whole” subject.

[5] So the musical subject speaks, moves, and intends. But what happens when the sense of musical cause and effect is attenuated or abandoned altogether? What happens to “the musical subject” when syntax is undermined by the obstinate repetition of a single motivic gesture? What domains of subjective experience can we map onto the “absence of volition” that this musical situation implies?

[6] The kinds of repetition that I have in mind include ostinati and minimalist techniques. These techniques are frequently described in terms of their effect of “stasis,” and interpretation often links them with an outright loss of subjectivity. But in musical practice, repetition techniques clearly serve a much wider variety of affective purposes.

[7] One explanation for this variation of affect is the fact that ostinati come in a variety of shapes and sizes. Richard Middleton offers a useful way to distinguish among different kinds of ostinati and their effects.(3) Middleton draws a distinction between what he calls “discursive” and “musematic” repetition strategies. Figure 2 summarizes this model. Musematic repetition is a more or less unvaried repetition of “musemes”—of motivic quanta, the smallest meaningful units within a musical system. Discursive repetition, on the other hand, is repetition of longer, syntactically more complex units, like whole phrases or strophes. The musematic strategy tends to project a single-leveled formal structurea “groove,” while the discursive strategy projects a hierarchically organized discourse—as in “strophic form”, for instance. The two strategies are differently weighted in different musical styles and they produce quite different experiential effects. Middleton conceives of these repetition strategies as two extremes on a continuum, with intermediate types lying somewhere in between. At the bottom of Figure 2 I show some examples of repetition categories and their relative positions on the continuum.

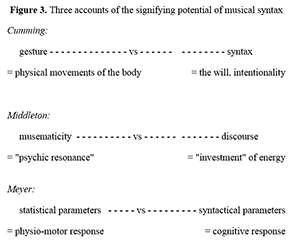

[8] Middleton argues that a purely musematic strategy will achieve a kind of “psychic resonance” for listeners, while discursive strategies will require more of an “investment of energy” from listeners. His account of discursive structures as “requiring energy” intersects with Cumming’s account of syntax as the site of intentionality. In other words, both authors connect the feeling of “willful effort” with the aspects of music that project hierarchy. Figure 3 compares the accounts of syntax we find in Middleton and Cumming. These distinctions between gesture and syntax, between the musematic and the discursive, resonate with Leonard Meyer’s distinction between music’s statistical and syntactical aspects. For Meyer, statistical or “secondary” parameters primarily involve physio-motor response while the syntactical parameters involve cognition.(4)

[9] I draw on the work of these scholars to reinforce the notion that a palpable sense of volition in a musical work has something to do with our awareness of hierarchies in the music. This suggests that, depending upon whether an ostinato is more “discursively” or more “musematically” oriented, repetition can tell very different kinds of stories about the musical subject. The internal structure of an ostinato itself, as well as its interaction with other lines or other ostinati, can suggest a subject with particular kinds of volitional attributes.

[10] Examples 1, 2, and 3 illustrate the qualitative distinction between musematic and discursive strategies. As you listen to these excerpts, consider what sort of musical subject emerges in each case—what sort of character does one “become”? And to what extent does the internal structure of the ostinato suggest attributes of that subject—not only the way it speaks and moves, but also the way it intends to speak and move.

Example 1. Raymond Scott’s Soothing Sounds for Baby, mm. 1–10

(click to enlarge and listen)

Example 2

Example 3. Arvo Pärt, “Arbos,” mm. 17–28

(click to enlarge and listen)

[11] Example 1 is a selection from Raymond Scott’s Soothing Sounds for Baby, a set of three albums of electronic music, released in 1964 under the auspices of the Gesell Institute for Childhood Development. The music is expressly intended for the listening pleasure of babies up to 18 months of age. Many grownups, however, enjoy these records too, perhaps because of their success in evoking an imagined oceanic state of contentment. The texture juxtaposes a purely musematic layer with a second, more discursively-conceived melody. The musical subject here might be understood as contained within a kind of safe holding environment, or in what David Schwarz has called “the sonorous envelope.”(5) As our attention shifts back and forth between the strictly musematic repetitions (shown in the example on the lower pair of staves) and discursive ones (represented by the top staff in the example), a dynamic interplay is setup in which agency is tentatively explored and then relinquished. We can imagine a musical subject which gently fluctuates between states of musematic “being” and discursive “becoming.”

[12] Now consider Example 2. This is a bit of Drum’n’Bass music by Spring Heel Jack, an excerpt from “Bells” from the album Busy, Curious, Thirsty from 1996. Interlocking layers in the texture present a graduated series of repetition strategies, from short, musematic “riffs” (such as the bass line) to longer, more discursively-structured units (such as the long descending chromatic line that emerges in the highest voice towards the end of the excerpt). Compared with Example 1, the musical subject here is a much more kinesthetically competent one, and one with a greater degree of volitional confidence. The differentiated periodicities of the layers in the hierarchical structure forge a palpable connection between the underlying volitional effort of the subject and its intricate gestures and movements.

[13] When differentiated ostinati are layered up in very dense textures, repetition techniques can suggest musical subjectivities of greater complexity. Consider, for instance, Example 3, a passage from Arvo Pärt’s Arbos. Example 3 configures a musical subject that contrasts with both the “infant” and the “dancer” in Examples 1 and 2. It might be described as more “contemplative.” For one thing, the ostinato phrase (marked with a beam in the example) is more expansive and more syntactically complex than what we find in Examples 1 and 2. In fact, the phrase marked here emerges from an additive process that occurs prior to the beginning of the excerpt. Moreover, these repeated phrases are embedded within the structure of a mensuration canon: units at the surface are generated from a slow-moving cantus firmus in the background. The title of the work, Arbos, suggests that the work attempts to create a musical analog for the structure of a tree. In fact Pärt claims to be representing something even more specific: a family tree. The remote lower layers of the texture are intended to represent familial ancestors to the generations propagating at the foreground. Pärt’s structure, then, suggests a whole constellation of musical personae: the more salient, faster-moving foreground figures suggest one kind of musical—a present, active, live subject (or perhaps several subjects)—while background structures suggest the ghostly presence of musical “others” in the work.(6)

[14] The creation of internal contrasts between musematic and discursive structures is one way that repetitive music can forge particular subjective identities. If the degree of “volitional will” of the musical subject is correlated with the sense of hierarchical organization, then the features of a particular hierarchy, such as its depth or granularity, will afford and constrain the musical subject’s identity in particular ways. Music that confounds hierarchic listening altogether because of a preponderance of undifferentiated “riffs” may suggest a “will-less” or “automatized” subject. Hierarchies that are shallow, with few levels, may suggest a tentative volitional state. In more highly stratified textures with differentiated levels of musematic and discursive parsing, the subject may be understood as more “willful,” provided the strata are perceived as hierarchically interlocked. Particularly deep or complex hierarchies or situations in which metrical relationships between figure and ground are ambiguous may suggest a split subject or a plurality of willful subjects.

Figure 4. Six repetition “tropes” with some representative works

(click to enlarge)

Example 4. Frederic Rzewski, Coming Together, mm. 18–37

(click to enlarge)

[15] Because ostinati may be constructed and combined in myriad ways, a variety of different kinds of stories can be told about musical subjects. Some of these stories are represented in Figure 4, a list of six “tropes,” along with some representative pieces, all of which employ the device of obstinate repetition. Naturally, the titles and other textual elements play an important role in determining the type of subject in each of these representative works, but I am speculating that the different personae associated with these tropes are created at least in part by structural relationships that obtain between surface and syntax in each musical situation.

[16] Musical examples 1, 2, and 3 appear on Figure 4 as representative works in the MATERNAL, the KINETIC, and the MANTRIC categories, respectively. The MANTRIC trope is designated as such because in these works the museme acts as a kind of mantra, whose endless repetition suggests access to mystical or spiritual transcendence. Several features work to make Pärt’s Arbos mantra-like: certainly the overriding harmonic consonance and the limited pitch resources of a single diatonic mode evoke a serene and contemplative state. But the mode of repetition itself and the measured transformation of musemes into discursive units are key aspects of the mantric effect. Furthermore, the tangible proportional relations that obtain among of the various layers represent the kind of complex hierarchical organization that suggests a multiplicity of mutually interdependent subjects—or a subject “in tune with the universe,” as it were.

[17] In the TOTALITARIAN trope, on the other hand, musematic repetition suggests a kind of “prison house” effect, an inability for the musical subject to break free of an obstinate musematic strategy. Here I am including works like Louis Andriessen’s De Staat, which sets Plato’s famous prohibitions against music-making. Frederic Rzewski’s Coming Together, inspired by the Attica prison riots, is another example, and since this work employs a number of techniques similar to those found in Pärt’s Arbos it is instructive to compare the two. Like Pärt’s Arbos, Rzewski’s piece adheres to a consistent diatonic mode throughout (G minor pentatonic) and employs additive processes. Despite these similarities, however, Coming Together manages to suggest a very different kind of musical subject. Aside from the explicit information conveyed by the text (a recitation of Sam Melville’s ominous letter), the mode of repetition itself expresses a kind of frustrated subject or suppressed volitional agency. As Example 4 shows, the gradual lengthening of the primary melodic pattern by a single note with each repetition initially suggests the potential for overcoming the obstinate musematic strategy. A short way into the piece, however, a subtractive process takes over, in which the pattern loses its starting note with each repetition. These processes, then, produce no eventual linear diegesis but only additional musemes. Coming Together by turns anticipates and retreats from discursive possibilities. The persistent musematic state is accentuated by the undifferentiated 16th-note tactus (unlike Pärt’s lilting iambs) which foils hierarchic parsing.(7)

[18] Coming Together thus draws upon some aspects of a fifth trope, the MOTORIC, where musematic strategies evoke an “indifferent” mechanized process. This situation arises most obviously in works where repetition is actually mechanical: think of Reich’s Pendulum Music (where suspended microphones swing rhythmically across upturned speakers to create repetitive feedback patterns) or Ligeti’s Poeme Symphonique (for 100 metronomes). A lack of telos is cultivated by composers in works that attempt to portray machines in motion—like Reich’s train music, or Michael Nyman’s Musique a grande vitesse. By relying exclusively on the kinds of tensional sets that Leonard Meyer describes as “statistical” vs. “syntactical,” these composers succeed in evoking a mechanized or “automatized” subject lacking the kind of subjective agency normally attributed to animate beings. Musematic repetition here implies a kind of single-step direct-access retrieval of previously stated musemes.

[19] What distinguishes the tropes described thus far is that each configures a different sort of musical subject—an infant, a dancer, a mystic, a prisoner, a machine—as the device of repetition takes on a unique subjective meaning in each case. Equally important, however, is that each trope also constructs a unique meaning for “syntax”—as repetition’s opposite. In the next part of this paper I would like to focus on the interesting case of what I call the APHASIC trope, where musematic repetition suggests a cognitively impaired musical subject. In these musical examples I am especially interested in how syntax, by its marked absence, takes on a special meaning and plays a role in expressing the character of the musical subject.

Example 5

[20] Consider how an imagined normative syntax plays a role in Example 5 (audio only), part of John Oswald’s “Pocket,” from his Plunderphonics collection of 1989. Because the source work here—Count Basie’s “Corner Pocket”—is (probably) known by a listener in advance, the effect of the obstinate repetition here is of a formerly cohesive Gestalt that has been damaged or shattered. The musematic repetition is understood to be in dialogue with some normative syntax, which remains present in the music like a kind of “phantom limb.” When discursive structures “deteriorate” into musematic ones like this, repetition can be linked with an image of cognitive dysfunction.

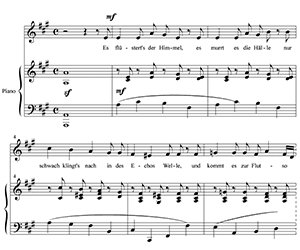

[21] In Michael Nyman’s opera The Man who Mistook his Wife for a Hat—based on the famous case study by Oliver Sachs—a similar process is employed to portray the main character in the opera: Dr. P, a singer, is the victim of a peculiar neurological condition which causes him to perceive visual information only in terms of primitive spatial schematics. In the second act of the opera, P’s aphasia is musically depicted in a particularly effective passage wherein the phrases of Schumann’s “Ich Grolle Nicht” from Dichterliebe are broken down into component musemes. This follows an earlier scene in Act II, where Drs. S and P perform the original Schumann song in its entirety. Example 6a shows the beginning of the Schumann song, and Example 6b illustrates how the passage is subsequently recomposed in the opera.

Example 6a. Robert Schumann, “Ich Grolle Nicht” from Dichterliebe, mm. 1–6 (click to enlarge) | Example 6b. Nyman, “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat,” mm. 601–622 (click to enlarge) |

[22] Elsewhere in the opera, Nyman makes reference to other works of Schumann: the passage shown in Example 7b, accompanies a scene, “The Dressing Ritual,” in which P puts on his clothes, which have been carefully arranged in an ordered sequence by his wife. He does this while humming a musematicized version of another Schumann song, “Rätsel,” shown in Example 7a.

Example 7a. Schumann, “Rätzel,” mm. 1–6 (click to enlarge) | Example 7b. Nyman, “The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat,” mm. 427–435 (click to enlarge) |

[23] The story does not concern Dr. Sach’s attempt at a “cure” per se for Dr. P’s condition, but rather his effort to come to grips with the way Dr. P experiences the world. As the neurologist gradually gropes his way through the bizarre terrain that is P’s radically schematic aphasia, the musical subject, likewise, gradually comes to learn what it is like to be Dr. P. Throughout the piece, a process in which discursive patterns deteriorate into musemes is applied again and again, not only to intertextural sources but to newly composed music as well, such as the main melodic theme of the Prologue. As the opera progresses, motivic elements become unglued from their discursive context and take on a life of their own as repeated musemes.

[24] Through this process Nyman creates a unique meaning not only for the technique of repetition itself, but also for syntax. While repetition represents the condition of aphasia, syntax acquires the status of something like “normal cognitive acuity.” In the other tropes listed in Figure 4, syntax takes on other sorts of meanings: if repetition is “infantile” in the MATERNAL trope, then syntax comes to represent something like “maturity”; when repetition signifies a frustrated or suppressed volitional agency, as in the TOTALITARIAN trope, then syntax is associated with “freedom.” This suggests that a linear diegesis—a musical process of cause and effect—cannot by itself be ascribed any stable or monolithic identity outside of a particular musical context. The signifying potential of both “syntax” and “gesture” are interdependently determined within a work.

[25] These examples, I hope, illustrate the point that techniques of obstinate repetition can achieve many different expressive ends. Each of these “tropes” configures the musical subject in a distinct way, by constructing different relationships between surface and syntax, between “discourse” and “musematicity.” If we are to understand something of the affective range exhibited by repetitive music, then our analyses must find ways to highlight the subtle interplay of these repetition strategies within works. As I have suggested in this preliminary study, one such analytical strategy would pay attention to the relative duration and complexity of repeated segments, the relationships among strata, the range of differentiation among musematic and discursive parsing within a piece, and the expressive nature of the vacuum that absent syntactical processes leave behind. Future research along these lines might specify precise criteria for the depth and granularity of hierarchic structures involving ostinati and determine the correlations between particular kinds of hierarchies and specific subjective and affective states.

Discography:

Rzewski, Frederick, Coming Together. Talujon Percussion Quartet: from their CD "...the speed of the passing time..." Capstone Records, 2001.

Michael Nyman. 1988. The Man Who Mistook His Wife For A Hat. CBS Masterworks MK 44669.

Jon Oswald. 1990. Plunderphonic. Mystery Tape Laboratory: 42P

Arvo Pärt. 1987. Arbos. Brass Ensemble Staatsorchester Stuttgart, DennisRussell Davies, conductor. ECM Records: ECM 1325./ ECM 831 959-2.

Raymond Scott. Soothing Sounds For Baby Vols 1,2,and 3. 1964 Epic Records:LN 24083--LN 24085

Spring Heel Jack. 1997. Busy Curious Thirsty Island Independent/Trade 2: 314-524 437-2;

Rebecca Leydon

Oberlin College

fleydon@oberlin.edu

Footnotes

1. Naomi Cumming, “The Horrors of Identification: Reich’s Different Trains,” Perspectives of New Music 35/1 (1997): 129–152; and “The Subjectivities of Erbarme Dich,” Music Analysis 16/1 (March 1997): 444.

Return to text

2. David Lidov, “Mind and Body in Music,” Semiotica 66/1–3 (1987): 69–97.

Return to text

3. Richard Middleton, “’Lost in Music’? Pleasure, Value and Ideology in Popular Music,” in Studying Popular Music (Open University Press, 1990).

Return to text

4. Leonard B. Meyer, Style and Music: Theory, History, and Ideology (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1989), 209. I am also reminded of Kevin Korsyn’s writings in which he has described the musical foreground as an “embodiment” of the subject and the Ursatz as the correlate of “consciousness.” See Korsyn, “Schenker and Kantian Epistemology,” Theoria 3 (1988): 44–50.

Return to text

5. David Schwarz, Listening Subjects: Music, Psychoanalysis, Culture (Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press, 1997).

Return to text

6. Pärt is, of course, referencing the techniques of organum purum. The deep structural cantus firmus can be understood as “generating” the surface oscillation of musemes throughout the piece. Yet while a listener can comprehend an underlying syntax, a kind of motivating agent in the work, it is not one that is necessarily available for subjective identification. Rather, it acts more as a remote, ineffable agent—for Pärt, representative of a “higher power,” perhaps, or even something like “atavistic memories.”

Return to text

7. In a performance of Coming Together, slower moving layers of the texture are improvised, based on elongated, rhythmically erratic doublings of the notated figures. Players are instructed to gradually transform these improvised lines into octave duplications of the notated music. One by one, the accompanying layers are thus absorbed into an undifferentiated unisoni foreground pattern. See performance instructions in Soundings 3/4 (July–October 1972), 44.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2002 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason and Tahirih Motazedian, Editorial Assistants