The Test Pressings of Schoenberg Conducting Pierrot lunaire: Sprechstimme Reconsidered

Avior Byron

REFERENCE: http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.07.13.2/mto.07.13.2.byron_pasdzierny.html

KEYWORDS: Sprechstimme, Schoenberg, performance, notation, recording, test pressings, Pierrot lunaire, analysis, singing, score, recitation, pitch contour, Stiedry-Wagner, Eine blasse Wäscherin, interaction, reproduction, real-time, deviation

ABSTRACT: Newly discovered recordings of Schoenberg conducting Pierrot lunaire open a window into the workshop of Arnold Schoenberg (the conductor) and Erika Stiedry-Wagner (who performed the Sprechstimme). These recordings reveal that in a period of not more than three days, Schoenberg accepted relatively great freedom in the Sprechstimme pitch contour; as well as a contradictory tendency towards consistency and a certain systematic approach towards pitch, which does not always adhere to the score. Before examining the recordings it was not possible to know whether the relation between the performed Sprechstimme and the score was controlled, systematic, or simply a matter of chance. The recordings shed new light on what has been described by Boulez, Stadlen and others as the “Sprechstimme enigma:” namely, how Schoenberg expected the Sprechstimme to be performed. The history of Schoenberg’s writings on Sprechstimme demonstrates that his perception of it changed along with the development of his performance aesthetics in general. Based on evidence from the recordings as well as on recent performance studies theory, I will claim that the Sprechstimme enigma is greatly clarified when one understands that there are simultaneously two types of notation in Pierrot lunaire: one for the instruments that tends towards a reproduction of a sound object, and another for the Sprechstimme which involves a process of greater real-time interaction between performer and score. Although the Sprechstimme from the workshop of Schoenberg and Stiedry-Wagner may be regarded as an extreme case study, it magnifies in a way what also happens in performances of other types of music.

Copyright © 2006 Society for Music Theory

INTRODUCTION

[1.1] In his 2005 article “Schoenberg as performer of his own works” Ronald Jackson speculated that it “is unfortunate that we have only one version of each of Schoenberg’s recorded works. Had he left more than one, how much more we would know about the kinds of freedoms he would have condemned or favored.”(1) Indeed the well documented web-site of Wayne Shoaf does not mention more than one recording of the very few that exist with Schoenberg conducting; the Arnold Schönberg Center web site has some further information but here too one can find only a single recording of each composition. Recently, I discovered several further recordings of Schoenberg conducting Pierrot lunaire. The first is a recording of a broadcast from 17 November 1940 in New York. The second is the test pressings of the 1940 commercial recording. The broadcast does not appear in any catalogue. The test pressings appear in a printed catalogue from 1986, yet they lay dormant for 65 years in Schoenberg’s Nachlaß since only now they were transferred in a very delicate and expensive process from LPs to CDs.(2) In this article I will focus on the test pressings.(3)

[1.2] Pierrot lunaire is considered by many as Schoenberg’s most famous masterpiece. For a long time the 1940 recording of Schoenberg conducting the piece was the only commercial recording available of his mature music.(4) Referring to it in a letter from 30 September 1940 to Moses Smith, Schoenberg claimed to be “very happy about the records.” The test pressings for the recording were made between 24 and 26 September 1940 in Los Angeles, in which the following musicians participated: Erika Stiedry-Wagner, recitation; Rudolf Kolisch, violin and viola; Stefan Auber, cello; Edward Steuermann, piano; Leonard Posella, flute and piccolo; and Kalman Bloch, clarinet and bass clarinet.(5)

[1.3] After the different test pressings were recorded they were given to Schoenberg to choose the best ones for the published recording. Dika Newlin, a student of Schoenberg, wrote on 2 October 1940 that Schoenberg had two or three test pressings of each side of the records. He wanted some “outsiders who were not quite as familiar with the music” to help him choose the best test pressing of each song. She reported that “Estep, Stein [other students of Schoenberg] and I were the only outside people there— Otherwise, there were performers and family: Kolisch with wife, Auber, Posella, Khuner, and Mrs. Seligmann.” Newlin claimed: “I vigorously participated in selecting the test pressings, a rather trickish job, since in many cases the differences were slight yet important.”(6)

[1.4] The test pressings include 16 records recorded on one side at 78 speed. These are not simply different performances. If up to now we had only a single picture of a historical event of Schoenberg conducting Schoenberg, now we have several pictures, or as it were—a short film of the very same occasion. This grants a rare opportunity to enter the workshop of the artist and observe not only the final product, but also the process of creation. It also provides a new perspective on the degree of stability and change of this historical interpretation.

[1.5] There are 34 test pressings (see Table 1). The songs “Eine blasse Wäscherin,” “Valse de Chopin,” and “Madonna” were recorded four times; “Gebet an Pierrot,” “Raub,” “Rote Messe” and “Galgenlied” were recorded three times. “Mondestrunken,” “Colombine,” “Der Dandy,” “Enthauptung,” and “Die Kreuze” were recorded twice; all the remaining nine songs were recorded once (not included in Table 1).

[1.6] One of the curiosities of Op. 21 is the Sprechstimme; and it is especially interesting when examining the singing of Erika Stiedry-Wagner in the recording with Schoenberg conducting. In this study I will focus mainly on Sprechstimme in the song “Eine blasse Wäscherin.”(7) Many commentators have noted that Stiedry-Wagner sings with an inaccurate pitch.(8) In Western art music, singing in a pitch that is inaccurate to some extent is not uncommon, yet in the performance of Stiedry-Wagner this is done in an explicit and exceptional manner. I will examine not only how accurately Stiedry-Wagner sings the pitches in “Eine blasse Wäscherin,” but also whether or not deviations are consistent in the four test pressings. If consistency may be found, it is interesting to consider its extent and whether it has greater implications on the understanding of how Schoenberg expected the Sprechstimme to be performed, and how Stiedry-Wagner built her performance? Finally, I suggest that a reconsideration of Sprechstimme in light of the test pressings has larger implications for understanding the role of the performer in relation to the score of many other musical works that were influenced by Pierrot lunaire or which influenced its creation, as well as of other works in Western art music.

THE SPRECHSTIMME ENIGMA

[2.1] David Hamilton has claimed that Schoenberg’s Sprechstimme “has been enormously influential in breaking the virtual stranglehold the bel-canto model of vocal production had maintained on Western Music— the vocal writing of Boulez, Crumb, Berio, and Maxwell Davis, for example, is unthinkable without Pierrot’s rupture of that fruitful but necessarily limiting monopoly.”(9) The Sprechstimme technique used by the speaker in Pierrot lunaire, as well as in other works by Schoenberg, has been described as posing “an enduring and perhaps insoluble interpretive enigma for the performer.”(10) Both Darius Milhaud and Pierre Boulez, who conducted the piece, described it as creating “insoluble problems.”(11) Boulez claimed that “although we possess authentic documentation on the subject, it is still difficult to form any precise idea of Sprechgesang.”(12) Lorraine Gorrell, who has performed the speaker’s role in Pierrot lunaire, reported the puzzling situation she found herself in when she approached the work. When listening to different recordings she discovered that “one performer sang the voice part, duplicating the pitches indicated in the score, while several other singers spoke the part but only vaguely approximated the indicated pitches.”(13) The recording of Pierrot lunaire made by Schoenberg also did not solve this problem since Stiedry-Wagner “did not match pitches or observe the indicated intervallic relationships. In fact, she sometimes did not even follow the direction of the indicated pitches. I began to wonder why Schoenberg had given pitches at all.”(14) A sense of the difficulty of performing Sprechstimme can be gained from the following report. Stiedry-Wagner said that Schoenberg and other members of the Society for Private Musical Performance

wanted first Gutheil-Schoder to [sing Pierrot lunaire]

. . . But it is a thing you have to talk, to speak, not to sing. And so she found it. . . too difficult, and then Alban said, “Why don’t you ask Erika Wagner? She’s an actress and she’s a singer,” because I also sang. I had Liederabende and I sang operettas. And so it happened that I did Pierrot. I studied it with Erwin Stein. . . I was working very hard, oh very hard. Because you know it’s very difficult to speak in rhythm—strong rhythm. And then the Sprechmelodie, you know. . . He wants a certain line to speak, with low tones and with high tones, and it is very difficult to keep the tone if you have to speak a word through one whole measure—a long time. It’s very difficult to keep it without singing. . . you need a very, very big Skala—deep and high and you have to be a Sprecher—you have to know how to speak, not how to sing, and that’s the main thing. And it’s very wrong—Schoenberg always told me it’s wrong—to sing. . . And this is really very difficult. So it was a Spezialität—a specialty for me.(15)

In several recordings—for example, one by Pierre Boulez and Yvonne Minton from 1977—one can hear a precise production of the Sprechstimme pitches indicated in the score, which Minton sings.(16) A performance decision which closely observes the pitch is not without sense since many of the songs contain significant pitch relationships between the Sprechstimme and the instruments. For example, in “Parodie” there are canons between voice and viola and between voice and piccolo. Yet “failing” to observe the indicated pitch is not only the practice of Stiedry-Wagner but also that of many other speakers.(17)

[2.2] Further problems were mentioned by Boulez when he wrote that there are “people the tessitura of whose singing voice is wider and higher than that of their speaking voice,” while with others the opposite may occur. He concludes that Pierrot lunaire “is thus both too high and too low.”(18) Also he pointed to the fact the when one speaks, the duration of the sound is usually short.(19)

[2.3] There have been several attempts to solve the Sprechstimme enigma. Peter Stadlen’s article “Schoenberg’s Speech-Song” from 1981 is a classic in the literature on Sprechstimme.(20) Yet this article has several weaknesses. First, it contains an implicit assumption that the performance of Sprechstimme should be identical or at least similar in all of Schoenberg’s compositions. Yet Schoenberg imagined different kinds of Sprechstimme in different periods and for different compositions; for example, in Pierrot lunaire he wanted the adherence to pitch to be greater than that in the Gurrelieder.(21) Stadlen’s article reviews what it sees as Schoenberg’s contradictory attitudes to Sprechstimme, with no relation to the contexts of his different performance aesthetics. Demonstrating how Schoenberg’s writings on Sprechstimme can be more fully understood in the light of his changing performance aesthetics is beyond the scope of this article, yet I will point to significant moments of change. Most importantly, I claim that this so-called contradiction appears only if one understands the role of the singer as that of reproducing the score or a sound object. My study will reveal that it is not that Schoenberg simply tolerated Sprechstimme performances that were not faithful to the score, but that he did not expect an exact reproduction of a sound object (at least with regard of the pitch parameter) from Stiedry-Wagner. We will see that Schoenberg’s acceptance of Stiedry-Wagner’s “out-of-tune” Sprechstimme was not due to limited musicality (she was after all more an actress than a singer), but something that was part of the conception of the piece. At the end of this article I will offer an alternative view to the role of the singer in Pierrot lunaire which much clarifies this so-called contradiction. In order to explain the contradiction that Stadlen wrote about I will further review the history of Schoenberg’s Sprechstimme.

[2.4] The origin of this technique has been traced to Engelbert Humperdinck in his 1897 melodrama Königskinder, as well as to the “old” Austrian theater speaking, yet Schoenberg’s Sprechstimme is a fresh and new conception.(22) Richard Kurth argues that “Schoenberg’s Sprechstimme is a representation of speech and a substitute for both speech and song. It emphasizes its own peculiarity and disorients the listener’s customary response to words’ sound and meaning.”(23) Schoenberg was influenced by Albertine Zehme’s original conception of Pierrot lunaire, and it is not unlikely that he was also influenced by her conception of recitation.(24) Zehme, who was deeply interested in the artistic and mystical sides of recitation, was the author of a treatise on the subject named Die Grundlagen des künstlerischen Sprechens und Singens from 1920.(25) In a note entitled “Why I must speak these songs” which she attached to one of her March 1911 Berlin performances, she wrote:

The words that we speak should not solely lead to mental concepts, but instead their sound should allow us to partake of their inner experience. To make this possible we must have an unconstrained freedom of tone. None of the thousand vibrations should be denied to the expression of feeling. I demand tonal freedom, not thoughts!

The singing voice, that supernatural, chastely controlled instrument, ideally beautiful precisely in its ascetic lack of freedom, is not suited to strong eruptions of feeling—since even one strong breath of air can spoil its incomparable beauty.

Life cannot be exhausted by the beautiful sound alone. The deepest final happiness, the deepest final sorrow dies away unheard, as a silent scream within our breast, which threatens to fly apart or to erupt like a stream of molten lava from our lips. For the expression of these final things it seems to me almost cruel to expect the singing voice to do such a labor, from which it must go fourth frayed, splintered, and tattered.

For our poets and composers to communicate, we need both the tones of song as well as those of speech. My unceasing striving in search of the ultimate expressive capabilities for the “artistic experience of tone” has taught me this fact.(26)

This “unconstrained” expressive conception of the role of the voice, which expresses something that is more than “the beautiful sound alone,” will be one of the keys to understanding Schoenberg’s puzzling concept of Sprechstimme.

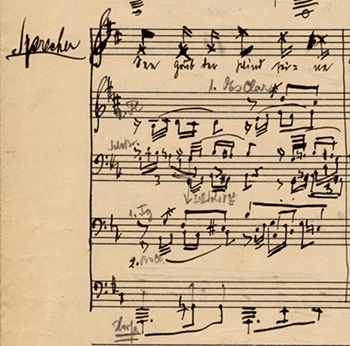

[2.5] On a page from a working autograph of Die glückliche Hand, Op. 18 from

September 1910 Schoenberg explained that the notes with crossed stems “must be

spoken at exactly the prescribed time and sustained as indicated; the pitch is

to be realized approximately through speech.”(27)

The first (complete)

manuscript of Pierrot lunaire had no preface, yet on the page of “Gebet an

Pierrot” (which was the first song to be composed in the cycle) from about March

1912 Schoenberg wrote: “The recitation should hint at the pitch.”(28)

In a

letter to Berg from 14 January 1913 Schoenberg wrote: “Regarding the melodramas

in the Gurrelieder: the pitch notation is certainly not to be taken as

seriously as in the Pierrot melodramas. The result here should by no means be

such a songlike Sprechmelodie as in the latter

The pitches in Pierrot depend on the range of the voice. You have to consider them ‘well’ but not ‘strictly’. You can divide the range of the voice in as many parts as half tones are used; perhaps then every distance is just a 3/4 tone. But you don’t have to carry this out in a pedantic way, because the pitches do not realize harmonical proportions. Of course the range of the speaking voice is not enough. Well, the lady has to learn to speak with ‘head voice’; every voice can do that

. . . The most important thing is to get the ‘Sprechmelodie’.(34)

The following suggestion by Erwin Stein, which appeared in an article in the journal Pult und Taktstock in 1927, seems to correspond to the indication in the early preface (and not the one that appeared in the published score) and these letters:

Though shown in absolute pitch notation, the intervals are only meant to be relative. The initial note is so short that it is of no harmonic consequence. The reciter is therefore free not only to transpose his part according to the type of his speaking voice and regardless of the other instruments, but also to narrow down the compass and tessitura

. . . What is essential is that the proportions of the melodic line be retained: a high note has to be relatively high, a low note relatively low; a fourth must be a wider leap than a third, and a minor second a smaller step than a major second.(35)

On 13 May 1927 Schoenberg wrote to Stein from Berlin that this article was

‘an excellent article, full of clarity, intelligence and understanding.’(36)

[2.6] Yet a very different conception of Sprechstimme can be found in the 1914

preface that Schoenberg wrote to the first printed edition of Pierrot lunaire:

The melody indicated by notes in the part of the speaker (with certain specially indicated exceptions) is not intended to be sung. The performer has the task of transforming it into a speech melody by taking well into consideration the indicated pitches. He can do this by

I. keeping to the rhythm just as precisely as he would when singing, i.e., with no more freedom than he would take in a sung melody;

II. being quite conscious of the difference between a sung tone and a spoken tone: the sung tone maintains its pitch without change, the spoken tone touches upon it but then leaves it immediately by descending or ascending. The performer must always be on guard against falling into a “singing” manner of speech. That is absolutely not intended. But neither should he aim for a realistic-natural speech. Quite the opposite, there should always be a clear difference between customary speech and speech that contributes to a musical effect. But this should never remind one of song.(37)

The demand for “taking well into consideration the indicated pitches” seems to contradict the mentioned above conceptions of approximation and suggestiveness of the Sprechstimme in relation to the notated pitch. Stadlen suggests there was “a conflict, from the very beginning, in Schoenberg’s mind between a desire for speech character and another, seemingly incompatible desire for an exact rendering of the notes.”(38) However, this is only a restatement of the problem and not its solution.

[2.7] There is something strange in Schoenberg’s instructions in this version of

the preface: how can the “indicated pitch” be communicated if one must

immediately deviate from it? Schoenberg’s demand for the speaker to perform her

part in a manner which is neither singing nor normal speaking leaves the

performer in a state where clear performance instructions are not to be found.

This places considerable responsibility on the performer—a responsibility that

may lead to unpredictable results. Indeed, the many recordings of this piece

demonstrate the diversity of the interpretations of the Sprechstimme part that

have been made up to now.(39) Richard Kurth writes: “At once both speech and

song, Sprechstimme is also neither

[2.8] On 16 August 1922, Schoenberg wrote to the singer Marya Freund concerning Pierrot lunaire: “I am anxious to explain to you why I cannot allow any will but mine to prevail in realizing [dargestellten] the musical thoughts [musikalischen Gedanken] that I have recorded on paper, and why realizing them must be done in such deadly earnest, with such inexorable severity, because the composing was done just that way.”(42) The reason for this severity, as well as for the relatively great silence by Schoenberg during the 1920s on the issue of Sprechstimme, might be that he was too influenced by and aware of the anti-interpretation movements of the 1920s, such as the Neue Sachlichkeit, to correspond on a matter which grants the performer such great freedom from the score. Several of Schoenberg’s writings contain complaints about performers in the 1920s who interpreted the score too freely;(43) the concept of Sprechstimme as it appears in Pierrot lunaire demands respect for the score on the one hand, while also requiring a freedom of interpretation on the part of the speaker, something which to Stadlen seemed contradictory. Yet what exactly needs to be realized here? What exactly are these musical thoughts? I believe that it is clear neither from this letter nor from other evidence that reproduction of pitch is the main issue (note that Schoenberg had put emphasis here on the severity of the process of composing).

[2.9] Christian Schmidt quotes the following passage from Schoenberg’s instructions in Moses und Aron: “The musician often cannot refrain also from melodically notating these mere speech figures. But also these are not to be sung. Evidence: they are beyond the 12 tones! But perhaps the singer should extract out of the [melodic] line what expression to conceive.”(44) Also Edward Steuermann, Schoenberg’s disciple and the pianist who performed Pierrot lunaire since its beginning, claimed: “It seems to me one has to find the expression of each sentence that will cover an entire line.”(45) Schmidt asks whether the Sprechstimme notated is “music-for-the-eyes” (Augen-musik) and if it was notated only because the composer could not release himself from the responsibility of relating to harmonic, counterpoint, and motivic-thematic ideas?(46) Schmidt does not answer his question but rather claims: “Doubt is advisable, and will arguably also remain.”(47)

[2.10] A different attitude than in the 1920s can be found in the last decade or

so of Schoenberg’s life. On 31 August 1940 he wrote to the Stiedrys: “We must

[2.11] In 1949 Schoenberg wrote in “This is my Fault” as follows:

In the preface to Pierrot lunaire I had demanded that performers ought not to add illustrations and moods of their own derived from the text. In the epoch after the First World War, it was customary for composers to surpass me radically, even if they did not like my music. Thus when I had asked not to add external expression and illustration, they understood that expression and illustration were out, and that there should be no relation whatsoever to the text. There were now composed songs, ballets, operas and oratorios in which the achievement of the composer consisted in a strict aversion against all that his text presented.(49)

Indeed we will see that in the recording from 1940 Schoenberg allowed Stiedry-Wagner to make unnotated changes in her Sprechstimme that have a direct correlation to the mood and character of the text. In other words, the indication from the preface of Pierrot lunaire should be understood in its historical context and not necessarily as the definitive, or most significant, wish of the composer.

[2.12] In a letter to the conductor Hans Rosbaud from 15 February 1949 Schoenberg claimed that the speaker in Pierrot lunaire “never sings the theme, but, at most, speaks against it, while the themes (and everything else of musical importance) happen in the instruments.”(50) Likewise, in a letter to Daniel Ruyneman from 29 July 1949 concerning Pierrot lunaire, Schoenberg wrote that “none of these poems is determined to be sung, but rather they must be spoken without fixed pitch.”(51) In these two cases Schoenberg emphasized the speaking side of Sprechstimme. Such an emphasis may have resulted from performers he had heard who simply sang the part. However negative performance experiences may not have been the only issue here at hand. Schoenberg’s performance aesthetics of that time did not advocate interpretations that negate the performer’s capacity to express him- or herself in ways that deviate from the strict indications of the score.(52) Sprechstimme in Pierrot lunaire has an in-built demand for interpretation by the performer; and when this is denied by performers, Schoenberg saw it as a misinterpretation of his music.

Example 1. Sprechstimme in Gurrelieder (this example is from 1900)

(click to enlarge)

Example 2. Sprechstimme in Ode to Napoleon (1942)

(click to enlarge)

Example 3. Sprechstimme in A Survivor from Warsaw (1947)

(click to enlarge)

Example 4. Sprechstimme in Modern Psalm (1950)

(click to enlarge)

Example 5. Notation of Sprechstimme without note heads in Pierrot lunaire in ‘Der Dandy’

(click to enlarge)

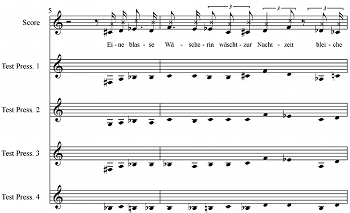

Figure 1. Comparison of Sprechstimme in the four test pressings of “Eine blasse Wäscherin”

(click to enlarge, see the rest, and listen)

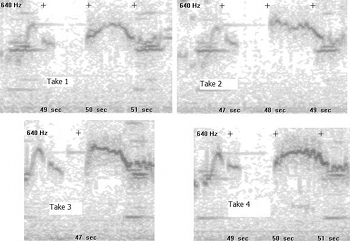

Figure 2. “Eine blasse Wäscherin,” m. 14, observance phrase peaks

(click to enlarge)

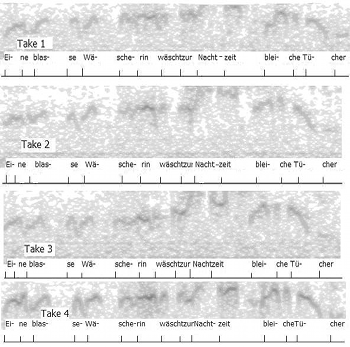

Figure 3. “Eine blasse Wäscherin,” rhythm in first phrase

(click to enlarge)

[2.13] On 2 January 1951 Schoenberg wrote to the Stiedrys that in contrast with Pierrot lunaire, the Sprechstimme in the melodrama of the Gurrelieder should relate “in no manner [to] pitches.” Schoenberg stressed: “I believe that I have written them only in order to represent my phrasing of the notes, the accentuation and the recitation more urgently. Therefore please no speech-melodies.”(53) This demonstrates that Schoenberg used the conventional notation of pitches in a non-conventional manner. Although he expected greater fidelity to pitch in the Sprechstimme of Pierrot lunaire than in that of the Gurrelieder, this does not mean that in Pierrot lunaire the performer should simply reproduce pitch. The fact that one can find structures in the pitch contour of the speaker’s part which are identical to those of the instruments and which correspond to similar compositional techniques, does not necessarily mean that these should be “brought out” in performance. Perhaps also in this case (as in Moses und Aron) the relations in the score are more part of the compositional process, and not necessarily to be communicated by performers and perceived by listeners.(54)

[2.14] The change in conception of the Sprechstimme in Schoenberg’s last decade or so of his life is also revealed in his new way of notating it in works such as Ode to Napoleon (1942), A Survivor from Warsaw (1947) and Modern Psalm (1950), where he used a single line (instead of five) for notating the approximate pitch of the speaker (see Example 1, Example 2, Example 3, and Example 4. In these works the speaker (or reciter, or narrator) is arguably discouraged from singing (compared to Pierrot lunaire). The fact that Schoenberg also used accidentals in this late type of notation may seem contradictory, yet this paradoxical situation seems to support his call for performers not to read his notation of Sprechstimme at face value. Similarly, Stadlen writes about the fact that in Pierrot lunaire one can find Sprechstimme notes with and without note heads (see Example 5). He concludes from this that the notes with heads should be sung at the given pitch. I would like to suggest that it is also possible that Schoenberg intended to grant the performers different levels of freedom where the notes without heads should be sung in an even freer manner than the notes with note heads. In other words, the fact that there are different types of notation here does not mean that notes with note heads must be sung in exact pitch. It is possible, again, that Schoenberg intended here three levels of interpretation: 1) notation of the instruments which should be precise with relation to pitch; 2) notation of Sprechstimme with note heads which may be less precise; and 3) notation of Sprechstimme without heads which grants the speaker even more freedom in determining the pitch.

ANALYSIS OF THE TEST PRESSINGS

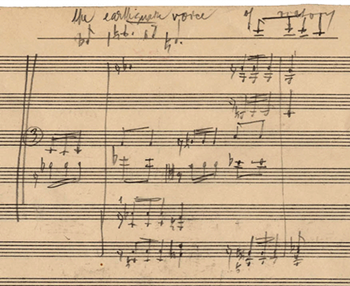

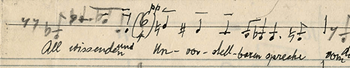

[3.1] I mentioned above Lorraine Gorrell’s observation that Stiedry-Wagner’s Sprechstimme is off-pitch. This is something that one notices immediately when analyzing Sprechstimme pitch in the different test pressings. However, the test pressings reveal further interesting information. Figure 1, which covers measures 5–17 of “Eine blasse Wäscherin,” has the Sprechstimme at the upper stave and the pitches of the four test pressings on the four staves below it.

[3.2] I used the computer program “gram” to detect Sprechstimme pitch. This program creates a spectrogram as in Figures 2 and 3. The user of the program can position the cursor on the spectrogram and the pitch is given in Hertz values. In Pierrot lunaire in general, and in our recording in particular, there is a special problem in deciding where to position the cursor; since Stiedry-Wagner often glissandos (see Figure 2) after and/or before the notated pitch (or its equivalent in her singing). In several cases I determined the pitch according to the dynamics—a place with higher dynamics (marked with darker black in the spectrogram—see for example Figure 2) was most likely the pitch which she tried to reach; or according to an average pitch, for example, when there was vibrato. Although the pitches of the test pressings in Figure 1 should be understood as an approximation, the possible degree of mistake is not larger than a quarter-tone and my transcription in Figure 1 is, therefore, accurate. In very few cases was there doubt about the exact pitch (for example, because of the voice being overridden by the instruments); these places appear in Figure 1 with a question mark. The duration, shown in Figure 3, was measured in relation to the commencement of each word of the text.

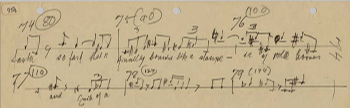

[3.3] It seems that Stiedry-Wagner allowed herself to transpose the pitch, usually, a third or fourth lower. Yet the transposition is not done consistently within the different test pressings: if one compares the four test pressings in measures 5–6, one will notice that except for test pressings 1 and 3 in measure 5, which are almost identical, all the rest start at different pitches and move within the phrases in a manner which is very free compared with one another (hear Sound Examples 1–4). A further comparison of these measures and others suggest that she did not have a strict idea of the intervallic content and the degree of transposition; and that much of this was improvised at that moment and changed from test pressing to test pressing. For example, the starts of the phrase in measure 5 was transposed a minor third to a fifth lower (depending on the test pressing), while the phrase beginning at the middle of measure 7 starts in test pressings 1 and 3 at the very same note as indicated in the score (and in the other test pressings—transposed not more than a minor second away)!

[3.4] Sometimes the pitch content of the notated melody seems to be almost completely ignored: in the phrase starting at the middle of measure 9 one can see that except for the movement in spaces of seconds and of a prima, there is little resemblance between the test pressings. In test pressings 2 and 4 there is a repetition of a single pitch (in each case a different one), something which emphasizes the speech character, yet which was not indicated in the notation (hear Sound Examples 5–8). Another example can be found in the middle of the phrase which crosses measures 13–14: the last four notes of measure 13 are different than those indicated in the score: in that Stiedry-Wagner does not reach the low point that Schoenberg notated. Yet here also, one can find a high degree of consistency among the test pressings, despite the discrepancy with the score.

[3.5] The examples mentioned above demonstrate the variety and liveliness of the singing of Stiedry-Wagner. The following examples will show that this improvisatory character was accompanied with a contradictory tendency towards stability. The start and end of the first phrase (measures 5–6) are very similar: the first three notes of test pressings 1 and 3 as well as the last three notes of test pressings 1, 2 and 3 accordingly have almost identical pitches. In contrast, the start of the phrase is more similar to the score than the end of it: there is consistency among the different test pressings and a very close resemblance to the score (hear Sound Examples 1–4). A similarity between the pitch of the test pressings and the score can be found also at the end of phrases (see the first note in measure 9) or at the start of phrases in many other places in the song: for example, the last two notes in measure 14, which are indicated to be sung, contain pitches very similar (indeed almost identical in this context) to those indicated in the score. When the notated pitch is systematically observed by Stiedry-Wagner in several test pressings it proves that it was not done by chance. Many times the exact pitch is not kept but the intervallic content is observed: the last phrase in measure 10 and the first one in measures 11–12 observe (by large) the direction and the intervallic relations of the notated melody. Note that the transposed starting tones as well as the ending ones in measures 11–12 are again similar if not identical among the different test pressings.

[3.6] In several cases one is obliged to notice a simultaneous tendency of change and stability in single phrases. The last two notes of the first phrase of the song (first two notes in measure 7) start a gesture with a pitch that is close to that of the score (first note) and ends much lower than indicated; the singer ignored the last pitch of this phrase in favor of a heightened expression of the prolonged gesture. A similar phenomenon occurs in measure 15 where the last two notes are supposed to be performed as a step upwards of a diminished fourth, yet in practice all test pressings contain a step upwards which is greater than an octave. A greater “exaggeration” can be found in the last two notes of the next phrase in measure 16.

[3.7] The phrase starting at the middle of measure 8 and ending at the beginning of measure 9 approximately observes the pitch of the peak of the phrase and that which ends it, while the pitch starting this phrase is usually between a fourth and a fifth higher than indicated (hear Sound Examples 9–12). The tendency to observe the pitch contour of phrase endings (in spite of variety in the body of the phrase) can also be found at the start of measure 10, and the end of measures 15 and 16. A tendency to observe phrase peaks can be found in measure 11 (see the high but especially the low point in the melody); and in measure 14 where she attempts (and usually succeeds in all test pressings) to reach the c'' twice (see Figure 2, Figure 1 measure 14 and hear Sound Examples 13–16). In measure 10 the c'' which is the peak of that phrase is transposed equally in all test pressings to g'. In measure 11 the beginning of phrase is transposed in test pressings 2–4 about a major third lower. In short, this consistency is not by chance and is probably a result of the singer paying more attention to the starts and ends of phrases.

[3.8] Most interesting are the places where there is consistency among the test

pressings which is contradictory to the direction of the melody in the score. It

is possible to see such a tendency in the last four notes of measure 6: at the word

“Nachtzeit” she is consistent in singing the first pitch higher than in the

previous word “Zur” and than going down; this is opposite to what is written in

the score (see Figure 3, Figure 1 measure 6 and hear

Sound Examples 9–12). See also the 4th and 5th notes of measure 12; the relation between the 3rd and 4th

notes of measures 14 and 16. This suggests that at times Stiedry-Wagner was

consistently performing a contour which was different from that in the score.

The consistency of her interpretation reveals that it was not pure

improvisation, and that this additional conscious or unconscious “structure” was

probably defined before performing the test pressings in the studio. The

performer’s “structure,” which is sometimes in contrast with the pitch in the

score, possibly fits the words better (at least from the point of view of the

singer). We saw that many years before the recording took place she studied this

composition with Erwin Stein, and that she remembered, even after so many years

had passed, that she “was working very hard, oh very hard;” and that Schoenberg

wrote to her just before the recording took place that they “must

[3.9] Another possible reason why Stiedry-Wagner “was working very hard” when preparing her interpretation was because “it’s very difficult to speak in rhythm—strong rhythm,” as she herself testified. I mentioned Schoenberg’s early preface written some time between March 1912 and January 1914: “it is the duty of the performer to perform the rhythm absolutely precisely;” as well as his 1914 preface arguing that the performer should keep “the rhythm just as precisely as he would when singing, i.e., with no more freedom than Figure 3. This figure must be read with caution, since what on paper may seem to be sounds with different durations may be perceived in listening as identical. Above Figure 3 one can find the rhythmic values of the first phrase. It seems that the words affect not only the pitch contour, as described above, but also the rhythm of the phrase. For example, in test pressing 3 the rhythm indicated in the score of the word “Nachtzeit” is distorted when the “Nacht-” turns out to be shorter than notated. One perceives the syllables of this word as of equal length. We can see that both rhythm and pitch contour are in contradiction with the score indication in this place. However, rhythmic deviations are usually not significant or systematic. The great deviations in pitch are compensated for by a rather strict adherence to notated rhythm. By fixing one parameter (rhythm) and giving much more freedom to another (pitch), Schoenberg created a situation where there is a mutual creation of musical meaning on the parts of composer and performer.

CONCLUSION

[4.1] The contradiction that is mentioned by Boulez, Stadlen and many other authors results from the 1914 preface that demands “taking well into consideration the indicated pitches” on the one hand, and the practice of Stiedry-Wagner (under Schoenberg’s conducting) not to do so on the other hand. Other evidence mentioned above, the claim that “pitch notation” should be taken seriously (1913), the early preface asking to keep “the relationship between the pitches,” Schoenberg’s 1922 letter to Maria Freund, and finally, his very act of notating exact pitches, all contribute to the sense that Sprechstimme must involve some serious relation to the notated pitch.

[4.2] Yet, Schoenberg also crossed the stems of the notes and wrote as early as 1912 that the “recitation should hint at the pitch.”(55) In Moses und Aron he points to the fact that Sprechstimme is beyond the twelve tones, and that the singer should extract from the notation the expression (as opposed to singing the exact pitches). If Boulez pointed out that themes in the voice part have relations to those in the instruments, Schoenberg, as if predicting this, claimed in 1949 that “the themes (and everything else of musical importance) happen in the instruments.” During the same year he even went so far as suggesting that Pierrot lunaire must be spoken “without fixed pitch;” and he developed in several late works a Sprechstimme with no conventional pitch notation. All this contributes to the feeling that the notated pitch is not to be observed strictly.

[4.3] It was well known that Schoenberg’s Sprechstimme invited diverging interpretations by various performers, that Stiedry-Wagner’s interpretation did not strictly observe the indicated pitch and that Schoenberg accepted such interpretations. What was not known was the degree of freedom that Schoenberg granted Stiedry-Wagner: it was not known whether the “correct” pitches that she sang were done so by chance or on purpose; it was further not known whether the “wrong” pitches were completely experimental, or had some relation (even if remote) to the score. This study of the test pressings reveals that there is a high degree of consistency in Stiedry-Wagner’s singing in several cases: some keep the exact pitch indicated in the score, some follow only the intervallic relations indicated in the score, and some do not observe the pitch melody of the score at all. The tendency to keep the pitch of the intervallic relations was especially prominent at melody peaks and phrase boundaries. The consistency among the test pressings was kept even when it was sometimes against the intervallic direction of the notated melody. One could never know whether Stiedry-Wagner’s off-pitch Sprechstimme was based on a new score that she created or whether it was purely a real-time experimentation; the test pressings, however, show a degree of freedom as well as of systematic behavior, and reveal that while Stiedry-Wagner prepared her Sprechstimme in advance (hence some of the systematic features), she left many aspects of her performance to real-time interaction (hence the variety among the test pressings).

[4.4] Stiedry-Wagner did not have a strict approach to the observance of notated pitch. In some of her performances the pitch was carefully observed, while in others merely “hinted” at. This, and the fact that places that collide with the score are consistent, suggests that she was working consciously or unconsciously with a performative contour that does not correspond to or deviate entirely from that of the score. In other words, it seems that Sprechstimme is meant to be constructed and highly influenced by the process of building an interpretation by the performer.

[4.5] Albertine Zehme and Stiedry-Wagner were actors and not professional singers; although, Stiedry-Wagner could control pitch since she sang in Liederabende and operettas. Except for praising her publicly for her performance in the recording, Schoenberg constantly chose her again and again (under his baton, that of Erwin Stein and others) for more than twenty years. This would not have occurred if her off-pitch singing would have been seen as problematic in his view. Furthermore, there are two famous stories of Schoenberg’s inability to recognize when a player used an instrument in a wrong transposition.(56) These stories are far from being simple descriptions of reality of Schoenberg’s ability to decipher pitch, since there is a heavy suspicion that these players were playing tricks on the composer; in addition, he may have been concentrating on other issues when conducting this extremely new music.(57) In other words, the assumption of limited ability on the parts of Stiedry-Wagner and Schoenberg to control or decipher pitch does not explain the Sprechstimmee phenomenon.

[4.6] Schoenberg’s Sprechstimme may be seen as a concept which resists the

view of music as solely the composer’s sound which needs to be reproduced by

passive performers. I mentioned above Albertine Zehme’s 1911 statement that

words are not merely concepts to be reproduced, but rather they “allow us to

partake of their inner experience” which is achieved by an unrestrained tone.

She concluded that “Life cannot be exhausted by the beautiful sound alone.” And

indeed, the revealed nature of the test pressings seem to suggest that Sprechstimme notation can be seen also “as a stimulus to the performer to

respond in a musically meaningful way,” and not only as a tool for reproducing a

sound object.(58) As mentioned above, the test pressings include both elements

which stay relatively stable among different test pressings, as well as changing

elements which support the view that performance “consists of an interpretive

engagement with the notation

[4.7] In a conversation between Adorno and Boulez about Pierrot lunaire, Boulez said:

I heard beforehand a very curious statement: Leonard Stein from Los Angeles told me once that, for example, when they were first rehearsing the Ode to Napoleon in Los Angeles, Schoenberg demonstrated a few passages himself, and it was completely different than notated, because for him the expression is in the end more important than the notation. For the author that is of course possible. But if one stands before the score as an interpreter, one has to initially have respect for the text; for if one distances oneself too far from the text, then it is no longer necessary to have a score, and perhaps I am therefore stricter than Schönberg. (Boulez laughs)(61)

Boulez’s preconception of respect to score that an interpreter must have (a “respect” that the composer himself did not seem to have) conveys a strong belief in the interpreter as a servant of the score that the creator (composer) communicates to the listener. If one takes seriously Schoenberg’s interpretations of his own music, it may be concluded that a different approach should be conducted by the performer. Indeed, Boulez and Adorno understand the absurdity of this view in light of Schoenberg’s practice and after Boulez laughs (at the end of the quotation above), Adorno answers: ‘You are in this respect truly more papal than the pope’. Boulez fails to see a middle way between adhering strictly to the score and not using it at all.

[4.8] If one understands the role of the performer as one of reproducing a sound object then Boulez and Stadlen are right in detecting a contradiction. However, the test pressings of Pierrot lunaire confirm that a perfect reproduction was not Schoenberg’s intention. Indeed, some aspects of pitch stay stable, and the rhythm is reproduced quite closely; however, the test pressings also reveal something new: the many changing elements and in some cases, their systematic nature, prove that great real-time interaction was expected from the speaker. The contradiction disappears if one understands the role of pitch not as one of a perfect reproduction (neither of pitches, nor of intervals) but as one that involves interpretative interaction in real-time. The 1914 preface indication that the “performer has the task of transforming it into a speech melody by taking well into consideration the indicated pitches” should be understood, I suggest, as a process of translation of pitch as if into a different language. Put bluntly, this means that the resulting pitches might be very different from those in the score. We saw above that Richard Kurth argues that Schoenberg’s Sprechstimme is a “substitute for both speech and song.” Also the other preface indication that “the spoken tone touches upon it but then leaves it immediately by descending or ascending” imply that an exact reproduction of the notated pitch (or intervals, or contour direction) is indeed not the main issue. The improvisatory yet systematic nature of the test pressings suggests that the “taking well into consideration” of pitch meant something different from reproducing exact pitch. What counts is not reproduction but a dramatic interpretive engagement with pitch, and more important with the text. In another place Stiedry-Wagner wrote that in performance with other singers sometimes people laugh, yet she argued that one must speak the part in a dramatic manner and that when she did so—no laughter was heard. Schoenberg wanted the speaker to carefully interact with the notated melody in a manner that will transform it; the aim of the hard work, mentioned above, that Stiedry-Wagner had done was not to reproduce the pitch but to transform it in a dramatic and improvisatory manner.

[4.9] The test pressings reveal what was previously almost unimaginable: Schoenberg accepted very different performances (although not completely different) of the Sprechstimme notation by Stiedry-Wagner in a period of not more than three days. It is not clear why Schoenberg decided to choose test pressing number 4 of the song for the commercial recording; the analysis of test pressings shows that faithfulness to the score was not a consideration since none of the test pressings is clearly preferable to others in this respect.

[4.10] It seems to me that in Pierrot lunaire there are actually two types of notations: one for the instruments which demands a relatively precise rendition of pitches; and one for the Sprechstimme which demands real-time interaction of the singer with the notation which creates a much higher degree of unexpected results. The fact that there are pitch structures in the Sprechstimme melody that have relation to the melodies in the instruments does not necessarily mean that these should always be “brought out” in performance. After all, compositional constructions that helped or fascinated composers in the process of composing—features that appear in the score yet are not necessarily to be perceived by listeners, is not an uncommon phenomenon in the history of music.

[4.11] Sprechstimme is indeed a bizarre phenomenon in traditional classical singing. Nevertheless, in many ways it magnifies what happens also in more conventional singing. Deviation from notated pitch, as well as a certain creative and systematic approach which refuses to be reduced to score indications, is frequent in many types of singing. In this sense it is possible to speak of a singer’s contour as a source which may have not less authority than what is traditionally known in music analysis as ‘the structure’ or ‘the melody’ notated in the score. This is of course valid also for much music of the twentieth century which includes singing techniques influenced directly or indirectly by Schoenberg’s Sprechstimme.

[4.12] The history of Schoenberg’s conception of Sprechstimme proves that he understood it differently in different periods. Schoenberg/Stiedry-Wagner’s 1940 workshop is after all only one historical occasion. Schoenberg was dealing with a particular performer, in a particular setting, and these constraints are perhaps somewhat contingent. Nevertheless, if one examines Sprechstimme history as well as the test pressings of the 1940 recordings, it is hard to avoid the notion that in spite the changes in conception, Schoenberg did expect that the singer will be always on a continuum (to use a metaphor coined by Cook)—more on the side of interacting with the score, and that the instruments will be more on the side of reproducing a sound object.(62) In this sense, the shifting and contextualized picture of Sprechstimme which I presented above does not contradict the larger context, namely that of an interaction-reproduction continuum. One can interpret this score while staying within the framework of Schoenberg’s general intentions about Sprechstimme (tending more towards the interaction side of the continuum in relation to the instruments), as well as what one may reconstruct as Schoenberg’s more local intentions (in 1940 or at any other period). Perhaps the greatness of this composition is that at different times, Schoenberg placed emphasis on different, and seemingly contradicting aspects, while keeping the larger spirit of the Sprechstimme in relation to the whole ensemble.(63) In this regard, Pierrot lunaire offers an endless variety of possibilities and musical meanings.

Avior Byron

Royal Holloway, University of London and Bar-Ilan University

Yoni Netanyahu 20, apartment 17

Givat Shmuel 54424

Israel

http://www.bymusic.org

avior.byron@gmail.com

Footnotes

1. Ronald Jackson, “Schoenberg as performer of his own

music,” in Journal of Musicological Research 21 (2005): 68.

Return to text

2. I would like to thank the Schönberg Center in Vienna and especially the

archivist Therese Muxeneder for agreeing to transfer test pressings to CDs.

Return to text

3. I would like to thank the University of London Central Research Fund for a

grant towards a research trip to the Arnold Schönberg Center in Vienna where I

conducted much of this study. All sound and notation examples were reproduced

here with the kind permission of Belmont Music Publishers.

Return to text

4. Arnold Schoenberg, conductor, Los Angeles, CA, (24–26 September 1940), CBS MPK 45695 mono ADD (1989) CD.

Return to text

5. This information can be found on the first page of the

conducting score: Schoenberg wrote in pencil “Records made/ September 24–26,

1940.”

Return to text

6. Dika Newlin, Schoenberg Remembered: Diaries and Recollections 1938–76 (New

York: Pendragon Press, 1980), 258.

Return to text

7. “Eine blasse Wäscherin” is one of three songs that have the largest number of

test pressings and which contains arguably the most interesting features of

pitch in relation to the other two.

Return to text

8. Standen, “Schoenberg’s Speech-Song” (see footnote 20); A. Hettergott, “Die

Sprechgesangstimme ins Pierrot lunaire Op. 21 von Arnold Schoenberg,” PhD

dissertation (Wien, 1993); See also Hettergott, “Sprechgesang in Arnold

Schoenberg ‘Pierrot lunaire’,” SMACS 93—Proc. Stockholm Music Acoustics

Conference, Royal Swedish Academy of Music Publ. No. 79 (July 1993): 183–190;

and Hettergott, “Sprechgesang-Vergleich individuell-interpretativer Unterschiede

in Schoenberg’s ‘Pierrot lunaire’.” Proc. DAGA 95 Saarbrücken (1995); Eliezer

Rapoport “Schoenberg-Hartleben’s Pierrot lunaire: Speech—Poem—Melody—Vocal

Performance,” Journal of New Music Research 33, no. 1 (March 2004); and Marinella Ramazzotti, “Klangfarbenverschmelzung von Stimme und Instrumenten in Pierrot

lunaire,” in Report of the Symposium: Arnold Schönberg in Berlin, 28.–30.

September 2000, Journal of the Arnold Schönberg Center (March 2001): 145–159.

Return to text

9. David Hamilton, “Moonlighting,” in From Pierrot to Marteau (Los Angeles,

California: University of Southern California, Arnold Schoenberg Institute,

1987), 46, originally from The New Yorker, 8 April 1974, 46.

Return to text

10. Bryan Simms, The Atonal Music of Arnold Schoenberg 1908–1923 (New York:

Oxford, 2000), 132.

Return to text

11. William W. Austin, Music in the 20th Century (New York, London: Norton,

1966), 196.

Return to text

12. Pierre Boulez, “Speaking, Playing, Singing” in Jean-Jacques Nattiez

(ed.),

Orientations, Martin Cooper (trans.) (London, Boston: Faber and Faber, 1990),

330.

Return to text

13. Lorraine Gorrell, “Performing the Sprechstimme in Arnold Schoenberg’s Pierrot

lunaire, Op. 21,” in Journal of the Singing 55, no. 2 (November/December

1998): 5–15.

Return to text

14. Ibid.

Return to text

15. Joan Allen Smith, Schoenberg and His Circle: A Viennese Portrait (New

York, London: Schirmer Books, 1986), 99–100. I made minor corrections in the

English of this quotation.

Return to text

16. Sony Classical SMK 48466 stereo ADD (1993) CD.

Return to text

17. For an example of a notated comparison of an expert by the singers Stiedry-Wagner,

Semser, Howland and Pilarczyk (all performed before 1965), see Austin, Music in

the 20th Century, 199.

Return to text

18. Boulez, “Speaking, Playing, Singing,” 330.

Return to text

19. Ibid.

Return to text

20. Peter Stadlen, “Schoenberg’s Speech-Song,” Music and Letters 62,

no. 1

(January 1981).

Return to text

21. See Schoenberg’s letter to Berg dated 14 January 1913. Juliane Brand, Donald

Harris, and Christopher Hailey (eds. and trans.) The Berg-Schoenberg

Correspondence: Selected Letters (New York: Norton, 1987), 143.

Return to text

22. See Rudolf Stephan, “Zur jüngsten Geschichte des Melodrams,” Archiv für

Musikwissenschaft 17 (1960): 183–92. For the relation of Pierrot lunaire to

the “old” Austrian theater of actors’ recitation such as Sarah Bernhardt and

Alexander Moissi (as well as that of journalist Karl Kraus) see Hartmut Krones,

“‘Wiener’ Symbolik? Zu musiksemantischen Traditionen in den beiden Wiener

Schulen” in Otto Kolleritsch (ed.) Beethoven und die Zweiten Wiener Schule, Studien

zur Wertungsforschung 25 (Wien-Graz, 1992), 53.

Return to text

23. Richard Kurth, “Pierrot’s Cave: Representation, Reverberation, Radiance,” in

Schoenberg and Words: The Modernist Years, Charlotte M. Cross and Russell

A. Berman (eds.) (New York: Garland Press, 2000), 211.

Return to text

24. Schoenberg was influenced by her earlier performances of Pierrot from

March 1911 in the way she selected the poems into three groups according to

subject. He also preserved her notion of “crafting a poetic narrative out of

Giraud’s loosely organized verses” (Simms, The Atonal Music, 124). Although

he created his own new narrative from the poems, he did retain Zehme’s

“narrative progression from lightness, to darkness, to death” (ibid., 125).

Return to text

25. Albertin Zehme, Die Grundlagen des künstlerischen Sprechens und Singens

(Leipzig: Carl Merseburger, 1920).

Return to text

26. Quoted in Bryan Simms, The Atonal Music, 120–21. Original German text can

be found at ibid. 235 note 21, and at Arnold Schönberg, Sämtliche Werke, Pierrot

lunaire, Josef Rufer (ed.) (Wien: Universal Edition AG and Mainz: Schott Music

International, 1995), Section 6, series B, 24/1, 307.

Return to text

27. Stadlen, “Schoenberg’s Speech-Song,” 3.

Return to text

28. The manuscript is called B in Schönberg, Sämtliche Werke, Pierrot lunaire.

“Die Rezitation hat die Tonhöhe andeutungsweise zu bringen.” The word

“andeutungsweise” can be translated also to “allusively,” “in outlines” and

“suggestively.”

Return to text

29. Schönberg, Sämtliche Werke, Pierrot lunaire, 143, my translation.

Return to text

30. The manuscript is called C in Schönberg, Sämtliche Werke, Pierrot lunaire.

Return to text

31. This emphasis is mine.

Return to text

32. “ist es Aufgabe des Ausführenden, den Rhythmus absolut genau wiederzu- /

geben, die vorgezeichnete Melodie aber, was die Tonhöhen anbelangt, in / eine Sprechmelodie

umzuwandelen, indem die Tonhöhen [deleted: zu] untereinander stets / das

[before correction: im] vorgezeichneten [sic!] Verhältnis einhalten.” The full

text can be found at Schönberg, Sämtliche Werke, Pierrot lunaire, 24.

Return to text

33. Erwin Stein to Arnold Schoenberg, 13 January 1921,

Library of Congress, Washington DC. “Es ist ganz unglaublich, wie eindeutig der

Ausdruck, auch seine Intensität, durch die Sprechintervalle fixiert ist. Man

spricht das nach, was dort steht und hat den Ausdruck, auch wenn man ihn gar

nicht empfunden hatte. Allerdings sind die Lagen-Unterschiede und die

Größenunterschiede der Intervalle sehr wichtig.” (Translation by Matthias Pasdzierny.)

Return to text

34. Arnold Schoenberg to Josef Rufer, 8 July 1923, quoted

as in: “Schönberg über Pierrot lunaire (Dokumente IV)” in Schönberg,

Sämtliche

Werke, Pierrot lunaire, 300. “Die Tonhöhen im Pierrot richten sich nach dem

Umfang der Stimme. Sie sind ‘gut’ zu berücksichtigen aber nicht ‘streng

einzuhalten’. Man kann den Umfang der Stimme in soviele Teile teilen, als

Halbtöne verwendet werden; vielleicht ist dann jeder Abstand nur ein 3/4-Ton.

Das muß aber nicht so pedantisch ausgeführt werden, da ja die Tonhöhen keine

harmonischen Verhältnisse eingehen. Die Sprechstimme reicht natürlich nicht aus.

Die Dame muß eben lernen, mit ‘Kopfstimme’ zu sprechen; das hat jede Stimme

Return to text

35. Erwin Stein, “The treatment of the speaking voice in ‘Pierrot Lunaire’,”

Hans Keller (trans.) in Erwin Stein, Orpheus in new

guises (Westport, Conn.: Hyperion Press, 1979), 88. Originally published in

Schoenberg-Issue of Pult und Taktstock (Vienna, March/April, 1927).

Return to text

36. Arnold Schoenberg to Erwin Stein, 13 May 1927, Library of Congress,

Washington DC. ‘Das ist wieder ein ausgezeichneter Artikel, Voll Klarheit,

Klugheit und Verständnis’. (Translation by Matthias Pasdzierny.)

Return to text

37. Translation based on Simms, The Atonal Music, 133–34.

I preferred “taking well into consideration” to “careful rendition” when

translating: ‘Der Ausfuhrende hat die Aufgabe, sie unter gutter Berucksichtigung

der vorgezeichneten Tonhohen in eine Sprechmelodie umzuwandeln.’ Original text in German

can be found in Schoenberg, Dreimal sieben Gedichte aus Albert Girauds “Pierrot

lunaire,” Forward.

Return to text

38. Stadlen, “Schoenberg’s Speech-Song,” 4.

Return to text

39. See Friedrich Cerha, “Zur Interpretation der Sprechstimme in Schönbergs Pierrot

lunaire,” Heinz-Klaus Metzger and Rainer Riehn (eds.), Musik-Konzepte, Schönberg

und der Sprechgesang 112/113 (2001).

Return to text

40. Kurth, “Pierrot’s Cave,” 223.

Return to text

41. Klaus Kropfinger summarized some of them as follows: “While on the one hand

Albertine Zehme’s performance was characterized as fluctuating appropriately

between ‘pathos and parody,’ thus avoiding the reproach of mannerism (National Zeitung, Oct. 11, 1912), from another point of view an absolute ‘unculture of

speaking’ was ascribed to her (R. L-s., Müncher Neueste Nachrichten, Nov. 7,

1912). Marya Freund, who was the reciter in performances under Darius Milhaud in

France and England and—according to Milhaud—tended all too much toward

singing, was criticized for this in numerous reviews. Others, however, among

then Vuillermoz (Le Temps, Jan. 27, 1922) and Koechlin (Le Monde Musical,

Feb. 13, 1922), assessed her performance of the Sprechstimme positively.

Koechlin even characterized the glissando which she produced thereby as ‘souplesse

singulière.” (Klaus Kropfinger, “Pierrot lunaire: Some aspects of its

reception,” in From Pierrot to Marteau (Los Angeles, California: University of

Southern California, Arnold Schoenberg Institute, 1987), 44.)

Return to text

42. Arnold Schoenberg, Letters, Erwin Stein (ed.), Eithne

Wilkins and Ernst Kaiser (trans.) (London: Faber and Faber, 1964), 74. Emphasis in

original. “Ich möchte gerne über manches, die Aufführung meiner Werke

betreffendes, mit Ihnen sprechen. Denn es liegt mir daran, Sie darüber

aufzuklären, warum ich bei der Verwirklichung der von mir in Noten dargestellten

musikalischen Gedanken keinen anderen Willen als den meinigen gelten lassen kann,

und warum bei dieser Verwirklichung dieser blutige Ernst, diese nachsichtslose

Strenge angewendet werden muß: weil mit ganz derselben komponiert wird.” Arnold

Schoenberg Center Web Site (correspondence),

http://www.schoenberg.at/6_archiv/correspondence/letters_database_e.htm

Return to text

43. See for example Arnold Schoenberg, Style and Idea, Leonard Stein

(ed.),

Leo Black (trans.) (London: Faber and Faber, 1975), 342–343, 346.

Return to text

44. “Der Musiker kann es oft nicht unterlassen, auch diese reine Sprech-stelle

melodisch zu notieren. Aber auch dieses ist nicht zu singen. Beweis: sie steht

außerhalb der 12 Töne! Vielleicht aber entnimmt ein Sänger aus der Linie,

welcher Ausdruck mir vorschwebt.” (T. 17ff) Schönberg, Sämtliche Werke, Moses

und Aron, Reihe A, Band 8, Teil 1(1977), 4. Schmit quotes this at his “Das

problem Sprechgesang bei Arnold Schönberg” in Pierrot lunaire: A collection of

musicological and literary studies, Mark Delaere and Jan Herman (eds.) (Louvain,

Paris, Dudley: Editions Peters, 2004), 83.

Return to text

45. First appeared in Gunther Schuller, “A conversation with Steuermann,” in

Perspectives of New Music 3 (1964–65): 22–35. Quoted here from Edward Steuermann, The Not Quite Innocent Bystander: Writings of Edward Steuermann,

Clara Steuermann, David Potter and Gunther Schuller (eds.); Richard

Cantwell and Charles Messner (trans.) (Lincoln and London: University of Nebraska Press,

1989), 172–173.

Return to text

46. Schmit, “Das problem Sprechgesang,” 84.

Return to text

47. Ibid., 85.

Return to text

48. “Wir müssen auch die Sprechstimme gründlich auffrischen—mindestens, denn

ich beabsichtige diesmal zu versuchen, ob ich nicht Vollkommen diesen leichten,

ironisch-satirischen Ton herausbekommen kann, in welchem das Stück eigentlich

konzipiert war. Dazu kommt, dass sich die Zeiten und mit ihnen die Auffassungen

sehr geändert haben, so dass, was uns damals vielleicht als Wagnerisch, oder

schlimmstenfalls als Tschaikovskyisch erschienen wäre, heute bestimmt Puccini,

Lehar und darunter ist.” Arnold Schoenberg Center Web Site (correspondence),

http://www.schoenberg.at/6_archiv/correspondence/letters_database_e.htm.

Return to text

49. Schoenberg, Style and Idea, 145–46.

Return to text

50. Stadlen, “Schoenberg’s Speech-Song,” 7.

Return to text

51. “keines dieser Gedichte zum Singen bestimmt ist, sondern ohne fixiermeasuree

Tonhöhe gesprochen werden muss.” Arnold Schoenberg Center Web Site

(correspondence),

http://www.schoenberg.at/6_archiv/correspondence/letters_database_e.htm.

Return to text

52. See for example: Arnold Schoenberg, Documents of a Life: A Schoenberg

Reader, Josef Auner (ed.) (New Haven and London: Yale University Press),

301–308; and Schoenberg Style and Idea, 320. The changing aspects of

Schoenberg’s performance aesthetics are discussed in Avior Byron, “Schoenberg as

Performer: an Aesthetics in Practice,” PhD dissertation (University of London,

2006).

Return to text

53. “zum Unterschied vom Pierrot, handelt es sich hier in keiner Weise um

Tonhöhen. Dass ich doch Noten geschrieben habe geschah nur, weil ich glaube so

meine Phrasierung, Akzentuierung und Deklamation eindringlicher darzustellen.

Also bitte keine Sprechmelodien.” Arnold Schoenberg Center Web Site

(correspondence),

http://www.schoenberg.at/6_archiv/correspondence/letters_database_e.htm.

Return to text

54. A third possibility is that they may be “brought out” only in a partial

manner—“hinted at,” to use Schoenberg’s own jargon.

Return to text

55. Emphasis mine.

Return to text

56. Arnold Schoenberg, “Der kleine Muck. The Concertgebouw

Revisited,” introduction by Leonard Stein, Jounal of Arnold Schoenberg Institute

2 (1977/1978): 105. See also Arnold Schönberg, Berliner Tagebuch, Josef Rufer

(ed.) (Berlin: Propyläen Verlag, 1974), 34. Passage translated by Jonathan Dunsby

in Arnold Schoenberg, “Der kleine Muck,” 106. I would like to thank Ethan Haimo

for his comments on this issue.

Return to text

57. A discussion concerning these stories and about Schoenberg’s conducting technique in general can be found in Avior Byron,

“Schoenberg as conductor,” Min-Ad: Israel Studies in Musicology Online 1

(2006)

http://www.biu.ac.il/HU/mu/min-ad/06/Byron_Schoenberg.pdf

Return to text

58. For recent Performance Studies theory on this, see Nicholas Cook, “Prompting

Performance: Text, Script, and Analysis in Bryn Harrison’s etre-temps” in Music Theory Online 11.1 (March 2005): [14]

http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.05.11.1/mto.05.11.1.cook_essay.html

Return to text

59. Ibid., 16.

Return to text

60. Jane Manning, “A sixties ‘Pierrot’: a personal

memoir,” Tempo 59 (2005): 25.

Return to text

61. “Theodor W. Adorno/Pierre Boulez, Gespräche über den Pierrot Lunaire,” in Heinz-Klaus Metzger and Rainer Riehn

(eds.), Schönberg und der Sprechgesang,

Musik-Konzepte 112/113 (July 2001): 85–86. The conversation was conducted on

26,27 November 1965, NDR.

Return to text

62. “In the same way, Goehr’s ‘perfect performance of music’ and ‘perfect musical performance’ might be seen not as opposed paradigms but rather as

contrasted emphases, opposed but in the sense of occupying distinct positions

within a continuum (with Stockhausenian elektronische Musik and free

improvisation perhaps defining its limits).” Nicholas Cook, “Between Process and

Product: Music and/as Performance,” Music Theory Online 7.2 (April

2001): [20]

http://societymusictheory.org/mto/issues/mto.01.7.2/toc.7.2.html

Return to text

63. Schoenberg’s fascinating remark in a letter dated 25 December 1941

concerning Stiedry-Wagner never being in pitch is discussed in Avior Byron,

“Schoenberg as Performer: an Aesthetics in Practice,” PhD dissertation

(University of London, 2006).

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2006 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason, Managing Editor and Tahirih Motazedian, Editorial Assistant