Duplicated Subdivisions in Babbitt’s It Takes Twelve to Tango *

Zachary Bernstein

KEYWORDS: Milton Babbitt, tango, rhythm, subdivision series, twelve-tone system, anomalies, gesture, Joseph Dubiel

ABSTRACT: It Takes Twelve to Tango (1984) has a subdivision series that unfolds in two dimensions: globally in the first beat of the 2/4 meter, and locally in the second beat. Though the eight subdivision series expressed in the second beat mostly proceed at the rate of one subdivision per measure, occasionally a subdivision will be repeated in two consecutive measures. Attempts to interpret these duplicated subdivisions reveal intersections between the subdivision series and a wide variety of other aspects of the piece, including the pitch-class array, hypermeter, and registral gestures. These non-systematic explanations lead to a meditation on the meaning and power of the systematic aspects of Babbitt’s music.

Copyright © 2011 Society for Music Theory

[1] In 1983, pianist and former professional ballroom dancer Yvar Mikhashoff launched the audacious International Tango Collection. Over the next eight years, this project would result in the commission of 126 tangos for solo piano by 126 composers. Among the many composers represented whose work is not often associated with the tango are John Cage, Otto Luening, Ralph Shapey, Karlheinz Stockhausen, and Milton Babbitt.(1)

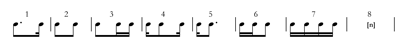

[2] It Takes Twelve to Tango (1984), unlike most of Babbitt’s music after 1960, does not use the time-point system.(2) The rhythms in the piece express a series of subdivisions of a quarter note into sixteenth notes, shown in Example 1.(3) In a gentle bow to the terpsichorean conceit of the piece, Babbitt does not supply a metronome marking for this quarter note, indicating only that the piece should be played “Tempo di Tango.”(4)

[3] This series progresses through the eight possible combinations of attacks on the second, third, and fourth sixteenth notes. As the first sixteenth note is always attacked, the piece has a regular, audible pulse. The last member represents the empty set and is filled by a string of even note values whose attacks do not intersect with any of the possible sixteenth-note attack points except the first. These even notes may divide the quarter note into one (that is, it may be undivided), three, five, or seven. The series proceeds via gradual development, each subdivision until the last only differing from the previous by either the addition or subtraction of one attack or the shifting of one attack by one sixteenth note. Since the first two subdivisions present the habanera rhythm common in tango, this gradual development produces a steady move away from the familiar pattern (Barulich and Fairley). The series may be grouped into four pairs: the first two subdivisions have two attacks each, the third and fourth have three, subdivisions five and six begin a progressive filling of the beat, and the final two divide the beat evenly. The absence of sixteenth notes in the final subdivision means that each presentation of the series ends with the impression of a ritardando (division into one or three) or a flourish (division into five or seven).

Example 2. Measures 1–12 of It Takes Twelve to Tango, with the subdivision series and semiblocks indicated above the staff and the aggregate boundaries indicated with vertical lines

(click to enlarge)

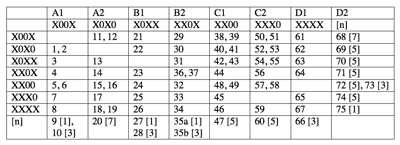

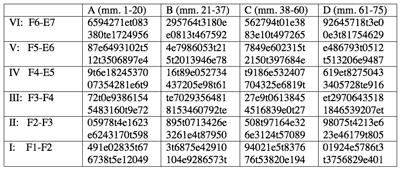

Table 1. Subdivisions of the quarter note in It Takes Twelve to Tango

(click to enlarge)

[4] The subdivision series is unfolded in two dimensions: at a global level in the first beat of the 2/4 meter, and more locally in the second beat. Each subdivision is repeated in each successive first beat seven to twelve times before proceeding to the next subdivision, presenting the series once over the course of the piece. These repeated subdivisions effectively divide the piece into eight sections, which will be called “semiblocks” for reasons to be explained shortly. Within each of these semiblocks the second beat proceeds quickly through the series, presenting each subdivision once or twice. The series presentations in the second beat either omit the subdivision simultaneously being heard in the first beat or present it after the final subdivision of the series.(5) Example 2 shows the subdivision series as realized in the first eleven measures of the piece.

[5] The subdivisional structure of the entire piece is depicted in Table 1.(6) Most combinations of subdivisions appear in only one measure, but some appear twice in two consecutive measures. The proliferation of non-sixteenth note divisions in the first beats of the last section represents the furthest point of development in the overall shift away from the habanera rhythm. There is a touch of reconciliation in the last bar because its first beat is not subdivided, which means the measure as a whole suggests a return to the prevailing sixteenth note divisions.

[6] Table 1 reveals a nearly complete progression through the sixty-four possible combinations of these subdivisions as well as an intriguing pattern of subdivisions that are repeated. Before getting to possible interpretations of these duplicates, I should mention that every rhythmic feature discussed so far corresponds to aspects of the pitch structure. The fifty-eight filled slots in Table 1 each correspond to one of the fifty-eight aggregates of an array that uses all partitions of twelve lynes into parts of six or fewer elements.(7) That is, most aggregates extend over one measure (with the aggregate boundaries precisely at the barlines), but if there is a repeated subdivision they extend for two measures (this can be seen in Example 2). The array is divided into four nearly discrete blocks, which have complete statements of a series form in each of the twelve lynes, and eight semiblocks, which present six notes of a series form in each lyne, completing a Schoenbergian hexachordal aggregate in each of the six registers.(8) The semiblocks correspond to the columns of Table 1, which are labeled using letters and numbers to show the grouping of semiblocks into blocks. All of the semiblocks have seven aggregates except for B2 and C1, which have eight. The direct correspondence between subdivisions and aggregates explains why only the semiblocks with eight aggregates contain all eight possible second-beat subdivisions. Since the number of subdivisions and aggregates in semiblocks B2 and C1 is exceptional, the “extra” subdivision—that which is also found in the first beat and would normally be omitted in the second beat—is appended to the end of the semiblock and thus does not interfere with the established pattern (the situation is similar in semiblock D1; see footnote 6).

[7] The blocks are less strongly articulated than the semiblocks, but as discussed above, the subdivision series can be plausibly divided into four groups of two. This grouping of the first beat’s series corresponds to the pairing of semiblocks into blocks. Despite their less direct articulation, one may still want to consider the blocks as basic structural units, not just because they contain full twelve-tone series in each lyne, but because of the way dynamics are used.(9)

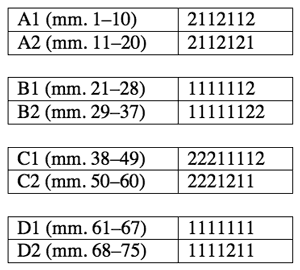

Table 2. Measures occupied by each subdivision and aggregate, in each semiblock

(click to enlarge)

Example 3. Dyadic invariance between inversionally related series forms (“t” and “e” indicate pitch classes ten and eleven respectively)

(click to enlarge)

Table 3. Disposition of twelve-tone series within lynes, blocks, and registers (C=0 throughout)

(click to enlarge)

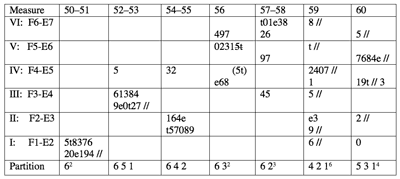

[8] Table 1 makes clear that though most members of the second beat’s subdivision series are stated once, some are stated twice; henceforth, these repeated subdivisions, which are also two-measure aggregates, will be called “duplicates.”(10) There are no obvious systematic reasons for the presence of duplicates—unlike, for instance, the repeated pitch classes in the array, which are needed in order to stretch forty-eight series over fifty-eight aggregates, or the repeated notes on the surface, which usually serve to create references to the series (these are necessary for the assignment of dynamics; see footnote 10)—but I will suggest a few possible interpretations for some of them. Table 2 represents the number of measures over which each subdivision (and thus each aggregate) is extended.

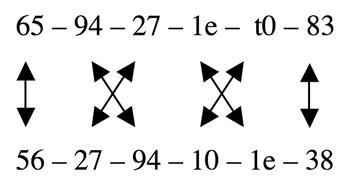

[9] One relationship that can be seen in Table 2 is that the pattern expressed in each semiblock is more similar to its counterpart within each block than it is to the pattern of any other semiblock. This reinforces the grouping of semiblocks into blocks. Table 2 also reveals that the pattern of duplicates groups blocks A with C and B with D, for A and C contain three or four duplicates in each semiblock, while B and D contain zero to two, and each semiblock in A and C begins with a duplicate, while none of the semiblocks in B and D begin with one. This connection between alternating blocks corresponds to another aspect of pitch structure.(11) The series class of this piece has the property of preserving each discrete dyad under a particular inversion, keeping the outer dyads in place while exchanging the inner dyads of each hexachord.(12) A demonstration of this is given in Example 3. This property is expressed in each lyne between blocks A and C, and B and D, as can been seen in Table 3.

[10] The duplicates at the beginning of the piece appear to set up something like four-bar hypermeter, for the duplication pattern in semiblock A1 can be heard as /211-211-2/ (see Example 2 for the score to this passage). Reading that pattern as hypermetrical requires understanding the emphasis of a duplicated subdivision or longer-than-usual aggregate as accentual, which is surely contentious and may not be generally applicable, but as the piece begins with the only unambiguous reference to a classic tango rhythm, heard twice in measures 1–2, it seems plausible to understand the beginning of the piece as similarly using the four-bar hypermeter most common in tango. The /211/ hypermeasure is also a fourfold expansion of the habanera rhythm itself, absent the sixteenth note. The pattern does not continue, for the beginning of A2 in measure 11 interrupts it, but it does return at the end of the piece. The only duplicate in semiblock D2 allows for its eight measures to be metrically analyzed as /1111-211/. There are at least two ways to understand this return. The touch of reconciliation that can be heard in the last bar for reasons discussed above may be supported by this return to the hypermeter of the opening. Or, it could be said that even though semiblock D2 is further away from the classic tango rhythm than any other part of this piece because it has non-sixteenth note subdivisions in the first beat of every measure, it is nonetheless grounded in the norms of the piece by this reference to the opening hypermeter.

[11] Duplicates are not evenly sprinkled throughout: two passages, measures 35a–43 and measures 48–58, are completely composed of them (except for measure 56). These two passages alone account for more than half of the duplicates in the piece. In addition, all of the missing expected attacks (listed in footnote 7) occur between measures 35 and 58. The presence of two-measure aggregates and missing attacks combine to create a substantial decrease in density, as measured by the rate of attacks and new pitch classes.

[12] The decrease in density is especially noticeable in the second passage composed of duplicates, for in the second measure of every duplicate between measures 48 and 58 there is at least one missing attack. The most noticeable missing attacks are the two expected to appear in the second beat of measure 49. The ties through those attacks create the only uninterrupted duration in the piece that extends more than five sixteenth notes; this sustain appears to function like a Grand Pause establishing an arrival in measure 50.

Table 4. The pitch-class array for semiblock C2

(click to enlarge)

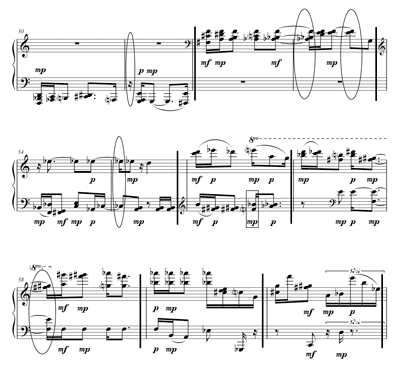

Example 4. Measures 50–60 of It Takes Twelve to Tango, with the aggregate boundaries indicated by vertical lines, the missing attacks indicated by ovals, and the transposed pitch classes in measure 56 boxed

(click to enlarge)

[13] This passage also features a dramatic focusing of register. Until measure 50, every aggregate but two (those in measures 21 and 44) is partitioned into at least three of the six distinct registers, but the three aggregates between measures 50 and 55 use only one or two registers.(13) The partitioning of measures 52–53 emphasizes this distinction by using adjacent registers and only the lowest note of the upper register, which means that the pitches in that aggregate are entirely contiguous. The array for the relevant semiblock is shown in Table 4, the full series forms used can be found in Table 3, and the score of this passage is in Example 4.

[14] Measures 50–58 use this registral focus to describe a gesture broader than any other in the piece. There is a gradual ascent from the lowest register in measure 50 to the highest register in measures 57–58. Pitch-class notation in the array obscures this a bit: measures 54–55 are higher than measures 52–53 even though IV is the uppermost register in both aggregates, because 5 is the lowest pitch class in that register (as in all others in this piece) and 3 is one of the highest. The array violations noted in Table 4, in which pitch classes 5 and t in measure 56 appear an octave lower than expected, make this registral gesture smoother by helping to bridge the gap between the highest and lowest registers.(14) Duplicates serve to extend a gesture implicit in five aggregates of the array over nine measures. The relative breadth of this section of the piece, caused by the duplicates, the long ascending gesture, and the missing attacks, ends quite suddenly in measure 59. There is a return to the use of all of the registers and one-measure aggregates, and the piece continues with both of these features until the end.(15)

[15] As noted above, the various interpretations given here for the presence of duplicates are not determined, or even much influenced, by the more systematic aspects of the piece. As Joseph Dubiel has argued, the actual power of the twelve-tone and time-point systems to strictly determine any given moment is usually vanishingly small, and there are no good reasons to necessarily prioritize “precompositional” explanations (cf. Dubiel 1997). But one thing these systems do provide is an interpretative context in which to think about curious anomalies such as the duplicated subdivisions or such apparent violations as the transposed pitches in measure 56. They may not provide answers to the questions raised, but they lead to situations in which interesting questions might arise, and suggest a language in which to speculate about them.

Zachary Bernstein

The Graduate Center, City University of New York

Music Department

365 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10016

zachbernst@aol.com

Works Cited

Babbitt, Milton. 1962. “Twelve-Tone Rhythmic Structure and the Electronic Medium.” Perspectives of New Music 1, no. 1: 49–79.

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/12116 (accessed May 26, 2011).

Baruch, Frances and Failey, Jan. “Habanera.” In Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online,

http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com/subscriber/article/grove/music/12116 (accessed May 26, 2011).

Dubiel, Joseph. 1992. “Three Essays on Milton Babbitt (Part Three).” Perspectives of New Music 31, no. 1: 82–131.

—————. 1997. “What’s the Use of the Twelve-Tone System?” Perspectives of New Music 35, no. 2: 33–51.

Hanninen, Dora A. 1996. “A General Theory for Context-Sensitive Music Analysis: Applications to Four Works for Piano by Contemporary American Composers.” PhD diss., The University of Rochester, Eastman School of Music.

Mead, Andrew. 1984. “Recent Developments in the Music of Milton Babbitt.” The Musical Quarterly 70, no. 3: 310 –331.

—————. 1987. “About About Time’s Time.” Perspectives of New Music 5, no. 1/2: 182–235.

—————. 1994. An Introduction to the Music of Milton Babbitt. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Ward, Amy. 2007. “Finding Aid for the Yvar Mikhashoff Collection of Tangos, 1983 – 1991.” State University of New York at Buffalo, Music Library, http://libweb1.lib.buffalo.edu (accessed May 30, 2011).

Wendland, Kristin. 2007. “The Allure of Tango: Grafting Traditional Performance Practice and Style onto Art Tangos.” College Music Symposium 47: 1–11.

Wintle, Christopher. 1976. “Milton Babbitt's Semi-Simple Variations.” Perspectives of New Music 14/15, vol. 14, no. 2–vol. 15, no. 1: 111–154.

Footnotes

* I’m grateful to Jeff Nichols and Joseph N. Straus for reviewing drafts of this essay, and to Daniel Colson for preparing the examples

Return to text

1. Ward 2007 and Wendland 2007, 1. Babbitt had collaborated with Mikhashoff in the earlier Waltz Project (1976–1978), for which he wrote Minute Waltz (or) 3/4 ± 1/8 (1977).

Return to text

2. An excellent recording of It Takes Twelve to Tango, performed by Edward Neeman, may be found on youtube. The time-point system was first discussed in Babbitt 1962.

Return to text

3. Other series of subdivisions of a regular beat appear in Semi-Simple Variations (1956) and All Set (1957). See Wintle 1976 and Mead 1994, 120–21.

Return to text

4. By dividing the duration of the piece indicated on the title page (ca. 2’30’’) from the length of the piece (152 quarter notes) one may estimate the tempo at approximately sixty quarter notes per minute.

Return to text

5. There is one exception to this pattern: semiblock D1 omits the fifth member of the second beat subdivision series, not the seventh as expected, and appends the seventh subdivision to the end of the semiblock (see Table 1). One consequence of this deviation from the pattern is that every beat from measure 63 through measure 67 has at least three attacks in it. This might be in order to accelerate in preparation for the outbreak of faster subdivisions during semiblock D2. Alternatively, this change could be said to sharpen contrast with D2 because it emphasizes relatively steady subdivisions as opposed to the more uneven rhythms to come.

Return to text

6. Measure 35 is four beats long, so it is apparently missing a barline or a time-signature change. I assume it is missing a barline because there are no other time-signature changes in the piece, and thus list two measures, 35a and 35b. There are three other apparent typos: there should be a bass clef in the left hand before the second beat of measure 29, the 8va begun in measure 38 should extend over the first beat of measure 39, and both occurrences of A6 in measure 32 should probably be C7 (this would complete the aggregate, avoid an anomalous octave, satisfy the linear counterpoint, and correspond to the dynamic scheme). Table 1 does not quite chart all of the rhythms in the piece: measures 31, 33, and 45 have sixteenth-note triplets in the place of expected eighth notes, and there are a few instances of expected attacks that are missing because of ties or rests (in measures 35b, 46, 49, 51, 53, 55, and 58). These missing attacks are almost all on the first sixteenth note of the beat, thus preserving the attacks that distinguish members of the subdivision series; the only exception is the ties through both expected attacks in the second beat of measure 49, discussed below. Curiously, all of the missing attacks except that in measure 46 occur during the second presentation of a duplicated subdivision. Perhaps since the subdivisions have already been heard, their literal restatement is less necessary. Table 1 obviously omits the many rhythmic, metric, and grouping subtleties suggested by intersections with other dimensions of the music, such as the dynamics and use of different registers.

Return to text

7. An aggregate is a single presentation of a complete gamut, typically the twelve pitch classes. A lyne is an uninterpreted string of elements, typically an ordering of the twelve pitch classes (i.e., a twelve-tone series). An array is an arrangement of two or more lynes sorted into partially ordered ensemble aggregates. See Mead 1994 for a detailed discussion of these terms. To the extent that the pitch structure completes an all-partition array but the rhythmic structure does not quite complete the sixty-four possible combinations of subdivisions, one may posit that pitch structure is conceptually prior to rhythmic structure. Despite much talk of analogies between pitch and rhythmic structures, I have noticed that Babbitt’s pieces often conclude with the completion of a maximally diverse pitch construct but well before the completion of a maximally diverse rhythmic construct (typically a time-point array). The array used here (part of which is seen in Table 4) is related to that in Paraphrases (1979) and Four Play (1984). The pitch-class series (seen in Example 3 and Tables 3 and 4) was also used in Images (1979). See Mead 1994, 159 and 271; and Mead 1984, 330.

Return to text

8. “Nearly” discrete because there are a few small overlaps across block and semiblock boundaries. By “registers” I mean the strictly delimited spans of twelve contiguous pitches in which each pair of hexachordally related lynes is realized (these are listed in Tables 3 and 4). The complex ways this concept of register interacts with more general, traditional notions of it are discussed in Dubiel 1997 and elsewhere throughout Dubiel’s work on Babbitt.

Return to text

9. The surface of the music is completely composed of references to the pitch-class series. Simultaneities are to be understood as ordered from bottom to top. Because the piece’s array uses each member of the series class exactly once (it is a hyperaggregate) and the series has no order-preserving invariances longer than two pitch classes (because there are no two segments of the series longer than two pitch classes that can map onto one another via the interval-preserving operations, nor any retrograde-symmetrical segments), each reference to the series that is longer than two pitch classes corresponds to a single place in the array. Dynamics are used as an index of distance between the reference and the source: if the reference is to a series form in the current block, the dynamic is piano; if the reference is to an adjacent block (on either side), the dynamic is mezzo piano; two blocks away is mezzo forte; and three blocks away is forte (this is similar to the dynamic scheme of About Time (1982); see Mead 1987, 127–18 or Mead 1994, 214). Since only the first and last blocks are three blocks away from another block (namely, each other), they alone have forte indications. Longer references to the series are marked by longer stretches without a dynamic change, though not all such stretches indicate long references because there are occasionally adjacent references to the same block. There are two references to the complete series, in measures 1–2 and in the last measure, measure 75. The reconciliation inherent in the last measure because of the return to sixteenth-note subdivisions is reinforced by the return to the series for the first time since the opening measures. Some of the difficulties regarding the perception of surface references to the array are discussed in Dubiel 1997.

Return to text

10. Duplicates can be seen in measures 1–2, 5–6, 9–10, and 11–12 of Example 2 and in measures 50–51, 52–53, 54–55, and 57–58 of Example 4.

Return to text

11. However, note that this connection cuts across the grouping indicated by the dynamics, which group the outer blocks separately from the inner blocks because of the presence of forte dynamics in the outer blocks; see footnote 10.

Return to text

12. As this transformation inverts each hexachord onto itself, it can be used for retrograde-inversional hexachordal combinatoriality if one of the series is reversed. This technique is found consistently in registers I and III.

Return to text

13. The presence of adjacent partitions with longer series segments (and thus fewer registers) is not in itself very notable, as it is apparently a necessary consequence of all-partition array construction (Hanninen 1996, 144). What is notable is the conjunction of these long partitions with other aspects of the music in order to create a broad ascending gesture, as discussed below.

Return to text

14. See Dubiel 1992, 118–119 for discussion of very similar circumstances in Canonical Form (1983). Dubiel suggests that certain violations of the array in that piece are also used in order to facilitate or heighten registral gestures.

Return to text

15. See footnote 6 for discussion of how this return to a faster pace interacts with the subdivision series in semiblock D1.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2011 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Michael McClimon, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits: