How Register Tells the Story in Scriabin’s Op. 22, No. 2 *

Martin Kutnowski

KEYWORDS: Scriabin, Schenker, Register, Voice Leading, Phrase Rhythm, Prototype, Phrase Expansion, Expression

ABSTRACT: In Scriabin's Prelude Op. 22, No. 2, published in 1897, register unleashes a conflict between phrase rhythm and voice leading. A four-measure prototype is first established; a registral singularity within the prototype forces a phrase expansion in the second half of the piece. This deliberate conflict reveals a sophisticated compositional voice and helps us appreciate the artistry of Scriabin’s style in his early piano works.

Copyright © 2011 Society for Music Theory

[1] In this paper I will show how a conflict between phrase rhythm and voice leading in Op. 22, No. 2, one of the Four Preludes by Alexander Scriabin published in 1897, is made salient by the composer’s use of register. This conflict reveals a sophisticated compositional voice and helps us appreciate the artistry of Scriabin’s style in his early piano works.

[2] Phrase rhythm conflicts are created when a symmetrical prototype is expanded or contracted. In this prelude, the expansion occurs in the second half of the piece. This is logical: modifications of the phrase structure are more effective if they happen against a defined expectation, which must be created first.(1)

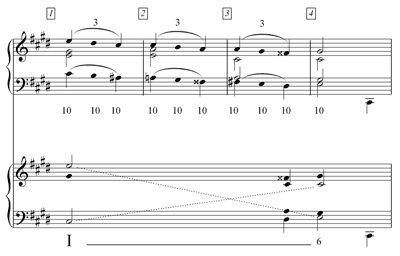

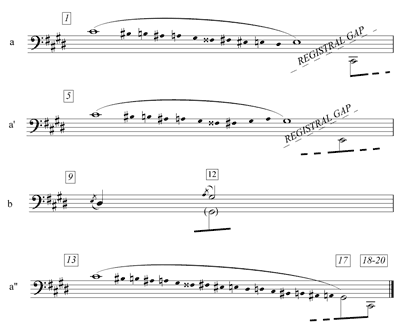

Example 1. Scriabin, Prelude Op. 22, No. 2, measures 1-4

(click to enlarge)

Example 2. Scriabin, Prelude Op. 22, No. 2, measures 5-8

(click to enlarge)

Example 3. Scriabin, Prelude Op. 22, No. 2, measures 9-12

(click to enlarge)

Example 4. Scriabin, Prelude Op. 22, No. 2, measures 1-18

(click to enlarge)

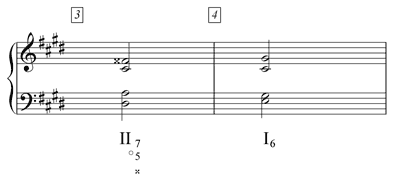

Example 5. Scriabin, Prelude Op. 22, No. 2, measures 3-4

(click to enlarge)

[3] The first level of Example 1 shows a dotted-quarter-note-level reduction of measures 1–4. This level also shows the underlying descending third progression in the bass, accompanied by parallel tenths in the top voice. The second level of the graph expresses the middleground content of the voice leading: a voice exchange from I to I6, with

[4] As shown in Example 2, we find the same agreement between the grouping structure and tonal rhythm in the second phrase (measures 5–8), although the harmony modulates at the end to the relative major, E. The harmonic reduction shows how the direction of the third progression, harmonized by tenths, has been modified to accommodate the modulation. This new instance of the four-measure unit solidifies the prototype, but once again, as in measures 1–4, a single instance of the low register (the “orphan” bass, E2) is detached from the rest of the “tenor” bass line.

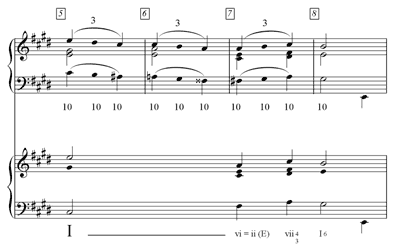

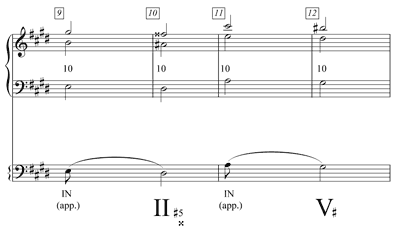

[5] Example 3 shows the following four-measure phrase, measures 9–12, introducing a new pattern, coincident with the seeming b section of a sixteen-measure “lyric form,” aa’ba’’.(2) The structure of this new phrase is [2 + 2]. In this case, the first two-measure unit is repeated almost literally, with a slightly modified transposition up a perfect fourth. The near transposition returns the music to

[6] At this point, we have been presented with three symmetrical four-measure groups. It is not unreasonable to think that the piece could have concluded with one more four-measure phrase (hypothetical measures 13–16). This would have created a square form, with four phrases in total, each exactly four measures long. But this is not what happens in the actual prelude. My claim is that such an ending would leave the question of the open registral space—between the tenor E3 and the orphan

[7] In a strictly linear dimension, the whole prelude represents the bass's journey from

[8] Example 4 also shows that the bass register is, at the background level, also coherently linked to itself: The bass voice in measures 4 (

[9] The linear and registral disruption of the fourth measure is also underscored with subtlety by the harmony. The cadence at measures 3–4 is comprised of a French augmented sixth chord in root position that resolves to a tonic chord in first inversion, as shown in Example 5. This progression, the resolution of an augmented sixth chord (in this case, an inversion thereof) to the tonic, is a common Russianism that works as a weaker cadential substitute for the never-reached dominant of the four-measure group comprising measures 1–4.(3) The same

[10] Another aspect of the prelude that deserves attention is the polyphonic nature of the top voice. Its contour defines two important separate melodic strands: one, which I call Soprano 2, shown in Examples 1, 2, and 3, accompanies the bass in parallel tenths through its chromatic descent. Always an eighth note too late, another strand (Soprano 1) appears in a higher register in measure 1, connecting

[11] An additional complicating factor of this section is the single slur between measures 11 and 16. Scriabin probably intended to cosmetically camouflage the structural joint between these two contrasting sections (b and a’’) as a way to avoid any sense of fragmentation.

[12] Crucially, the rhythmic displacement between Sopranos 1 and 2 is equal to the duration of an eighth note. Therefore, the displacement is motivically related—and symmetrically equivalent—to the rhythmic placement of the two registral levels (the “orphan” bass, and its tenor “sibling”) described above.

[13] As a rhythmic motive, the eighth-note displacement is present both in the incomplete upper-neighbor motive of the top voice and at the end of each a section. This motive generates the registral gap in the bass, which ultimately causes the phrase expansion. Perhaps this delayed reach towards the outer registers came to the composer more as an intuitive, purely pianistic, tactile impulse, rather than as a speculative compositional idea. After all, Scriabin had very small hands, and breaking these chords may have been the only way for him to actually reach all the notes.(4) To be sure, Scriabin avoided writing an arpeggio marking in these instances, which he could simply have done. Instead, it would seem that Scriabin made a virtue out of necessity, capturing the eighth-note delay that was perhaps inspired by the mechanical difficulty and turning it into a motivic-registral compositional feature.

Martin Kutnowski

Associate Professor of Music

St. Thomas University

Fredericton, New Brunswick

Canada E3B 5G3

martink@stu.ca

Works Cited

Bowers, Faubion. 1973. The New Scriabin: Enigma and Answers. New York: St. Martin's Press.

Burkhart, Charles. 1991. “How Rhythm Tells the Story in 'La ci darem la mano.'” Theory and Practice 16: 21–38.

—————. 1997. “Chopin’s Concluding Expansions.” In Nineteenth-Century Piano Music, edited by David Witten. New York: Garland Publishing, 95–116.

Huebner, Steven. 1992. “Lyric Form in Ottocento Opera.” Journal of the Royal Musical Association 117: 123–47.

Rothstein, William. 1989. Phrase Rhythm in Tonal Music. New York: Schirmer Books.

Schachter, Carl. 1995. “The Triad as Place and Action.” Music Theory Spectrum 17/2: 150–169.

Skryabin, A. N. 1948. Polnoe sobranie sochinenii dlia fortepiano, Vol. 2. Ed. Konstantin Nikolayevich Igumnov and Yakov Isaakovich Milshtein. Moscow: Muzgiz. Plate M. 18995 Γ; repr. n. d. (ca. 1990). Budapest: Konemann, Plate K 214. Accessed on January 3, 2011 from: http://imslp.info/files/imglnks/usimg/6/66/IMSLP68041-PMLP20242-Scriabin--Preludes-Op22--Ed-Muzgiz-Konemann.pdf

Tchaikovsky, Peter Ilyich. 1871. Guide to the Practical Study of Harmony. Trans. Emil Drall and James Liebling. Leipzig: Jurgenson, 1900; repr. New York: Dover Books in Music, 2005.

Footnotes

* The title of this analysis alludes to Charles Burkhart’s groundbreaking article on the aria from Mozart’s Don Giovanni, La ci darem la mano (see Burkhart 1991). The analysis is also inspired by Carl Schachter’s analysis of Chopin’s Prelude Op. 28, No. 4 (see Schachter 1995, 150–152).

Return to text

1. Burkhart 1997 identifies a specific type of expansion that, because of its recurrence, is one of the trademarks of Chopin’s style. My example is modeled after the ones offered in that article. Expansions or contractions of established phrase lengths are also discussed at length in Rothstein 1989, 64–101.

Return to text

2. “Lyric form” refers to a specific four-phrase form, normally aaba but sometimes aabc, as defined in Huebner 1992, 123–47. Lyric form is also called “quatrain” in Rothstein 1989, 107.

Return to text

3. The augmented sixth chord resolving to the tonic is extensively discussed in Tchaikovsky 1871.

Return to text

4. Comprehensive biographical information about the composer can be found in Bowers 1973.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2011 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Michael McClimon, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits: