Timbre as Differentiation in Indie Music

David K. Blake

KEYWORDS: timbre, independent music, phenomenology, My Bloody Valentine, Neutral Milk Hotel, Shins

ABSTRACT: The divide between “independent” and “mainstream” crucial to popular music discourses of the past twenty years has garnered scholarly attention from cultural studies and sociology, but not from music theorists. This paper argues that timbre, more than any other musical parameter, musically expresses differentiation from mainstream sounds in indie music. Phenomenological theories of Merleau-Ponty and Edward Casey are used to proffer a methodology of timbral analysis premised on contextually meaningful, complementarily perceived adjectives. Three case studies examining music of My Bloody Valentine, Neutral Milk Hotel, and the Shins exemplify this analytic framework.

Copyright © 2012 Society for Music Theory

[1.1] Scholars have long understood the ideology of rock-based Anglo-American popular music genres to be based on difference, whether against generational, political, generic, or indistinct hegemonic forces. This thesis has received special attention in scholarship scrutinizing independent or “indie” music, a motley collection of genres and styles (indie pop, indie rock, indie folk, etc.) unified through associations with small record labels, college or noncommercial radio, and alternative methods of distribution. Numerous studies have demonstrated how Indie music foregrounds discourses of differentiation against mainstream music from social, political, economic, and/or cultural perspectives, while it simultaneously profits from mainstream processes of institutionalized capitalism and social privilege (Lee 1995; Thornton 1996; Hesmondhalgh 1999; Hibbert 2005; Newman 2009; Dolan 2010). Such studies accurately describe the complexities of indie music’s claims of differentiation from a cultural standpoint, but they tend to obscure the genre’s most salient feature: the music. How does music serve to aurally project “independence” in indie music? How can extramusical differentiation connect with musical sound?

[1.2] This article asserts that timbre, more than any other musical parameter, expresses extramusical differentiation in independent music genres. Timbre is the primary vehicle by which indie music is produced and heard as different from its contemporaneous mainstream. Timbral choices intended as different from stereotypes of mainstream sound connect with discourses of differentiation on cultural, political, economic, and/or generic planes. I demonstrate this claim through three analyses that exhibit disparate connections between timbral difference and other forms of differentiation in indie music. I begin with an analysis of the opening guitar riff of My Bloody Valentine’s 1991 single “Only Shallow” to connect the sound’s inscrutability with an introverted yet aggressive masculinity linked with shoegaze performance. I then discuss Neutral Milk Hotel’s 1998 track “The King of Carrot Flowers, Part 1” to link accumulative build of warm timbres with an alternative masculinity and the desire to commune with, comfort, and love the song’s intended subject, Anne Frank. Lastly, I discuss the Shins’ 2001 album Oh, Inverted World to indicate how timbres are used in diverse ways to replicate 1960s pop, forging a soundworld separate from both contemporary mainstream music and other indie genres.

[1.3] Scholars such as Allan Moore and Chris MacDonald have focused on harmony as a marker of generic distinction, but I focus on timbre because harmony is not in and of itself sufficient for understanding extramusical differentiation. The basic chord structure of “The King of Carrot Flowers, Part 1,” for example, is I–IV–I–V–IV–I. This progression marks a distillation of the basic 12-bar blues progression heard frequently in early rock and roll, and is also heard in U2’s 1987 hit “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For” (Moore 1992, 95, 101). While Moore hypothesizes that certain harmonic patterns can differentiate rock/pop/soul music from jazz-derived genres, the vast differences among Neutral Milk Hotel, U2, and, say, Little Richard render the potential for shared differentiation through harmony untenable below this broader level (Moore 1992). Chris McDonald has hypothesized that alternativeness can be forged through “modal subversions,” or the crossing of major/minor through mediantly-related power chords (2000). While his study uncovers frequent use of I–

[1.4] Another critique of pitch-based approaches comes from indie music’s ontology as a primarily recorded genre circulating through technological mediation. Timothy Warner, for one, has argued that traditional analyses of popular music focused on notatable parameters ignore the impact of the recording process in shaping sound (Warner 2009). His alternative—a model of creativity—unfortunately strays from the sonic characteristics to social interaction. Yet, as Brian Eno claimed in an interview, “a fact of almost any successful pop record is that its sound is more of a characteristic than its melody or its chord structure or anything else. The sound is the thing that you recognize” (Korner 1986, 76). What Eno refers to when he says “sound,” as separate from melody or harmony, is timbre. This essay will thus test how recognizable characteristics of timbre as such can sonically connote differentiation.

[1.5] Arguing that differentiation is linked with timbre and not with pitch-based musical parameters like harmony addresses two methodological issues within the discipline of music theory. First, and most simply, timbre is problematic for traditional analytic methods. This paper begins by reviewing different methodologies for timbral analysis. I then propose a phenomenological alternative based upon the theory of motility in Maurice Merleau-Ponty and binaries of emplacement in Edward Casey. I combine these to connect the production of timbre with the projection of self-identity, and place the comprehension of timbre within a comparative analytic frame premised on contextually defined adjectives.

[1.6] Second, my thesis argues that pitch and rhythm are essentially subordinate to timbre for connecting musical and social practices. Foregrounding timbre contributes a new perspective to the well-trod battleground in rock music analysis between formalist and cultural methodologies. I conclude this essay by investigating recent rock music theory which, despite new and innovative perspectives on pitch- and form-based methodologies, subordinates timbre, and thus social context, by presenting songs as autonomous texts. I ultimately argue that a phenomenological approach to timbre dislodges textual autonomy and descriptive fixity in ways that could render rock music theory more relevant to the contexts of its social practice.

Timbre in Music Analysis

[2.1] Popular music scholars have long understood timbre as a formative aspect of popular genres, but have been perplexed when approaching it analytically. Formative texts in popular music analysis in both music theory and musicology acknowledge the primacy of timbre for producing musical meaning, but discussion quickly transitions to other, more approachable parameters (Shepherd 1987; Walser 1993, 41–44; Headlam 1997, 88). This is because timbre is especially frustrating for analytic description, at once the most apparent and least systematizable musical parameter. Robert Cogan and Pozzi Escot argue that “tone color is perhaps the most paradoxical of music's parameters. The paradox lies in the contrast between its direct communicative power and the historical inability to grasp it critically or analytically” (1976, 327). Ethnomusicologist Cornelia Fales explains this paradox further, stating that “we hear it, we use it . . . but we have no language to describe it. With no domain-specific adjectives, timbre must be described in metaphor or by analogy to other senses” (2002, 57).(3)

[2.2] The usage of metaphor and/or analogy in analytic methods is typically viewed as insubstantial and relativist.(4) Accusations of relativism are not due to the inability of timbre to be descriptive in of itself. Timbre can impart information like source location and materiality (Ihde 2007). Rather, convention has historically required visually accessible and quantifiable evidence. In Foucault’s words, “to observe, then, is to be content with seeing – with seeing a few things systematically” (1994, 134). Timbre is problematic for the kind of observation Foucault describes, both because it can only be accessed audibly in combination with other musical parameters (pitch, register, texture, etc.) and because it cannot be quantifiably systematized. Scholars since at least the time of Helmholtz have understood timbre to be formed by overtone combinations, but it is difficult to isolate or describe it except through employing discourses of difference. A 1960 definition of timbre by the American Standards Association, for example, claims the term “cover[ed] all ways that two sounds of the same pitch, loudness, and apparent duration may differ” (quoted in Slawson 1985, 19).(5)

[2.3] Difference has been an important feature of timbral definition, but its intrinsically negative operation—timbre is not that—fails to satisfy the question of what timbre is, and how it functions in music as a unique sonic parameter, central to more traditional analytic modes. The development of electronic music, and the resultant ability to parameterize sound, enabled the first scholarly attempts at timbral systemization in the late 1960s. Theorists studied timbre as an isolable musical parameter whose manipulation contributed to the structure of modernist music, both electronic and acoustic (Fennelly 1967; Erickson 1975; Cogan and Escot 1976; Chou 1979). Composers also explored timbral analysis for practical application (Schaeffer 1966; Slawson 1981, 1985; Boulez 1987). One particular problem faced by these scholars is that standard Western musical notation does not visually represent timbre, or does so at best obliquely. Attempted strategies to notate timbre range from drawing dotted lines between timbrally-connected sections of printed scores (Chou 1979) to developing entirely new notational systems analogizing timbral attributes and shapes (De Vale 1985).

[2.4] Spectrographs, which provide overtone charts of recorded sounds, have become a crucial tool for scholars interested in visual timbral representation outside of the notational orbit. They have been especially useful in describing timbral processes in both contemporary electronic music and vocal music where timbre is a more isolable variable (Cogan 1969, 1985, 1998; Cornicello 2000; Latartara 2008; see also Latartara and Gardiner 2007). David Brackett incorporated spectrographs into his influential 1995 text Interpreting Popular Music. Brackett recognized the importance of timbre in popular music, and employed spectrographs to provide concrete visual evidence for his claims about the vocal qualities of Hank Williams, Bing Crosby, and Billie Holliday. For Brackett, the advantage of spectrographs is that they allow for analysis of sound without need for aural perception. As he states, “the primary advantage of the automatic transcription [spectrograph] is that it allows us to observe musical elements that we do not hear, sounds that we change or distort in the act of hearing” (Brackett 1995, 29; italics in the original).

[2.5] And yet, timbre is dependent upon perception for its meaning. It is perceived within popular music not as a sonic essence comprehensible only through visualized overtone charts, but as a perception of phenomenal sound given a particular cultural context. Spectrographs certainly serve a useful scientific purpose by translating timbre to visible, quantitatively observable data, but they make for a clunky middleman when grappling with its phenomenal characteristics. Vocal qualities are simply illuminated more immediately by hearing rather than seeing overtone charts. One here might turn back to Slawson, who uses “sound color” to approach timbre’s ontology as “an attribute of auditory sensation” (1985, 20).(6) Slawson defines sound color as an auditory and perceptual phenomenon, but his study does not dwell on its perceptual qualities. Rather, he explores how mathematical operations on sound waves affect sound color as a parameterized sonic aspect. Slawson’s conception of “sound color” thus falls into the same trap as Brackett’s spectrographs by prioritizing visual representation over auditory sensation.

[2.6] Ethnomusicologists offer an alternative timbral methodology focused on connections between sound and social meaning (Feld 1982; Turino 1993; Sugarman 1997). Grant Olwage (2004) analyzes the timbre of South African black choral music through the bodily production of vocal sounds in the Xhosa language and its attendant difference from European vowel sounds. He connects timbral difference with connotations of “blackness” in South Africa. Olwage reinserts difference as a useful timbral heuristic connecting musical practices with the politics of South African racial binaries.

[2.7] But how can timbre be described as meaningful? Olwage, like many other scholars, turns to Barthes, who foregrounds the “grain” of the voice, or the erotics of its corporeal materiality. The concept of “grain” converts the description of sound to nouns as opposed to adjectives, which Barthes considers inadequate for relaying substantive meaning (1977; cited in Olwage 2004, 313–14). Yet the adjective, by its very definition, is descriptive; the problem is in its lack of objectivity, substance, and fixity. While the material grain of a sound is important, is not the adjective which apprehends its meaning, its power, its jouissance, equally so? Can its subjective qualities, through comparative methods, communicate analytic meaning within a given contextual framework? In order to recuperate the adjective, we must scrutinize the production and perception of timbre through a phenomenological framework. Specifically, Merleau-Ponty’s concept of motility (motricité) developed in his Phenomenology of Perception can usefully link timbral production with identity. Moreover, metaphors of place used by Edward Casey can illuminate how adjectives understood as comparative and contextual can usefully describe timbre.

Timbre and Intentionality: Musical Motility

[3.1] In his landmark Phenomenology of Perception, Merleau-Ponty centers perception in motility, or the way the embodied subject projects itself into the world. Merleau-Ponty defines motility as “basic intentionality. Consciousness is in the first instance...a matter of . . . I can” (1981, 137). Motility is a basic ability which causes the apprehension of objects, or in Merleau-Ponty’s words, a “being-towards-the-thing through the intermediary of the body” (138–39). Embodied consciousness is the basis for perception and orientation, which then forms the basis of significance and meaning (142).

[3.2] Though motility usefully embodies perceptual orientations, the concept has been critiqued for describing an unmarked masculine mode of perception. Iris Marion Young criticizes Merleau-Ponty’s formulation of motility by arguing that women project outward with an “inhibited intentionality” through their Othering by patriarchal society (2005, 36–37). Though Young erects a rather essentialist binary between active male and restricted female, her formulation is useful for depicting two groups with differing projective abilities. One group has unencumbered motility due to a linked identity with hegemonic social norms, while the other is hampered through perceived difference. Young undermines Merleau-Ponty’s conception of motility as “basic intentionality” by arguing that motility is always impacted by social factors.

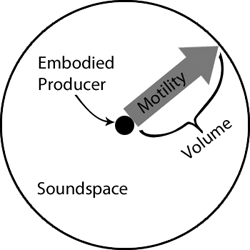

Figure 1. Diagram of motility within a sound space

(click to enlarge)

[3.3] Merleau-Ponty’s general thesis, filtered through Young, can be translated into recorded popular music through conceiving of “musical motility,” the projection of the self outward through sound into the recording. Musical motility allows the artist to project meaningful sound into a sound space, which in this article refers to the range of sound allowable in a recording. Musical motility, from Merleau-Ponty’s theory, assumes that sound is in some sense intentionally produced. Figure 1 clarifies my definition of motility. The circle represents a given sound space. The dot in the center is the musician, the embodied producer of musical sound. The arrow shows the projection of self through music within the sound space. Motility itself is the generative principle that creates the arrow and its particular shape and color. Motility enables the arrow to project outward from the producer within the medium of the sound space with characteristics perceptible to others.

[3.4] In Figure 1, we can describe the characteristics of the arrow through recourse to visual terms by discussing its color, shape, length, and border. If we imagine the arrow as a sound, we can describe its characteristics through timbre (except for length, which correlates to volume). Timbre should therefore be understood as the parameter most directly expressing musical motility. Recalling Young’s critique of Merleau-Ponty, timbre as motility articulates recorded sound with the lived politics of identity formation.(7) Theorizing the production of sound through motility, in short, asserts that sound is always intentionally (in some sense) produced within a social field, questioning the existence of “the music itself.”

[3.5] Focusing on timbre does not exclude the contribution of other parameters such as pitch, rhythm, envelope, texture, and register to motility. Each of these parameters impact timbre, whether through influencing perception of an individual sound or by providing syntactic context for timbral change. However, a phenomenological perspective foregrounds timbre as the musical parameter most directly connected with identity formation.

Emplacing Timbre, Emplacing Analysis

[4.1] If musical motility projects the self into sound, what is that self, and how can it be perceived by listeners and described by analysts? When looking at Figure 1, one can simply say the color of the arrow is gray. However, sound lacks the specificity of visual color words. With music, a producer may intend a sound to have a particular tone color, but due to the imperfect nature of human communication (never mind the semiotic flexibility of musical expression), those reasons may be subjective and, therefore, not easily discernable. The work of phenomenologist Edward Casey offers a way to meaningfully describe perceived sound through recourse to place. Casey argues that place is primary to embodied human perception. We make sense of the world through perceptual dyads premised upon a “somatic axis,” i.e., our embodied, perceiving selves (Casey 1993, 98). One of his perceptual dyads, “near-far,” has two characteristics which serve as a striking metaphor for our perception of timbre.

[4.2] First, near and far are complementary binaries understood as opposites of one another within the continuum of distance. However, their boundaries are “matters of degree,” which are “remarkably porous, taking on changing aspects of the situations in which they are imminent” (Casey 1993, 57). Near and far transition into one another gradually, and different places become near or far based on context and perception. Near and far are therefore “attuned to—and thus reflect—the particular way I am inserted into my life-world at a given moment” (58). The ontology of near and far requires both the embodied subject and the perception of directionality to exist: “Neither the near nor the far—much less their various concatenations—would appear without my corporeal intentionality, my directedness to the world through my bodily bearing” (59). Near and far are only comprehensible through contextual perception.

[4.3] Second, though near and far are understood as opposite phenomena, their boundaries cannot be precisely demarcated. Moreover, they should not be because they are “averse to exact determination.” Casey continues, “indeed, any effort to measure the near or the far—to gauge them, singly or together, on a scale of uniformly distributed marks or numbers—not only misses the phenomena themselves but undermines their very identity” (58). Near and far must be apprehended qualitatively since their edges and borders lack exactitude; quantitative definition fails to reflect their—and our—perceptual grounding.

[4.4] To summarize these two attributes, near and far have opposite definitions based on relative, perspectival, and contingent factors, and adhering to exact definitions undermines their perceptual ontology. Turning Casey’s discussion to timbre, many musical adjectives function as complementary terms within particular contexts. Binaries used to emplace sound within discourse (loud/soft, high/low, clean/distorted, etc.) are understood as different compared with another opposite term given a perceptual situation. Adjectives outside of binaries used to describe sound, such as “nasal” or “whirring,” can also be understood contextually in relation to other available sounds. Spectrographs have been used to fix definitions for these terms according to overtone properties, but they are unnecessary for perception. Such scientific formulations based upon specificities of overtone qualities may explain why a sound provokes a particular descriptor, but they simultaneously obfuscate the perceptual nature of the sounds being described.

[4.5] Casey’s theory illuminates three aspects of timbre crucial for analysis. First, timbre is only understood within a perceptual context given particular orientations. Second, timbre is understood comparatively within the perceptual context, not through absolute characteristics. Last, timbre is subjectively experienced, not objectively demarcated. Casey’s work also, importantly, can lead analysts to conceive of adjectives as meaningful, complementarily-perceived timbral descriptors. By mapping Casey’s prepositions onto timbral adjectives, I shift the object of timbral analysis from absolute properties of a sound to its relationship with immediate surroundings. I follow both Olwage and the earlier definition of timbre cited by Slawson to reaffirm that timbre is primarily understood through difference, an assertion that centers timbral ontology in embodied perception and projection. Timbral analysis must therefore be a strongly contextual endeavor. A turn toward particular contexts, however, does not entail a turn to relativism. Rather, a phenomenologically grounded timbral analysis must provide an accurate description of timbre, incorporating methods of musical production, resultant sonic characteristics, and meanings of sound within social milieus.

Audio Example 1a. Stone Temple Pilots,

“Plush,” 0:00–0:14

Audio Example 1b. Papa Roach,

“Last Resort,” 0:11–0:22

[4.6] Young’s critique of motility proffers two types of motility, one hegemonic and dominant, and one restricted and different. Young’s binaristic politics map remarkably well onto indie music, which perceives itself as different from hegemonic mainstream styles and masculinities.(8) Since the primary context of differentiation for most indie music is mainstream rock, the analyses to follow will use its timbres, especially the distorted electric guitar, as a point of comparison. The electric guitar has been theorized as a musical representation and projection of an aggressive, dominating masculine phallus (Bayton 1997; Waksman 1999; Millard and McSwain 2004; Laurin 2009). Using motility, the stereotyped guitar sound can be described as the aggressive, “amplified” projection of masculinity. Audio Examples 1a and 1b demonstrate this sound using the Stone Temple Pilots’ 1993 post-grunge single “Plush” and Papa Roach’s 2000 nu-metal track “Last Resort.”

[4.7] I wish to proffer four adjectives to describe this sound. The first is full, in that it aggressively fills the soundspace with a great deal of sound. “Full” implies both high volume and a timbral complexity that comes from the intermingling of overtones heard in power chords. The second is distorted; one hears distortion rather than a “clean” electric guitar sound. The third is digestible, which I use to mean that the distortion does not overtake the pitch and rhythm aspects of the sound. You can clearly hear the harmonic rhythm and backbeat in “Plush” or the stepwise progression of “Last Resort,” for example. Listeners familiar with either song, or similar examples, will further note that the guitar recedes into an accompaniment role backing the voice during the verses and choruses. The fourth, and most complex, is homogeneous. Homogeneity means both the lack of variety of sounds within the songs’ given soundscapes, and also the similarity of sounds between the two songs and larger generic expectations relative to the possible range of electric guitar sounds. While these are not the only potential adjectives to describe these sounds, they express aspects meaningful to listeners that can serve as points of comparison between other songs.

[4.8] As we will see, indie artists project timbres differentiated from this mainstream sound in some way in order to reflect a broader sense of differentiation. Motility is particularly appropriate for analyzing the production of indie music because indie musicians generally maintain agency over the circulating sound—that is, the circulated sound matches the projected sound. Casey’s concept of near/far enables a phenomenological analytic methodology premised on adjectival description that is sensitive to the varied kinds of sonic differentiation that occur within indie music. The three following examples demonstrate how indie groups use timbre to connect musical and extramusical differentiation within particular contexts.

My Bloody Valentine, “Only Shallow,” 0:05

[5.1] My Bloody Valentine’s 1991 album Loveless has become one of the most canonized albums in indie music. Pitchfork Media, the influential indie website, named the album the second best of the 1990s (Pitchfork Staff 2003), and “Only Shallow” the sixth best song of the decade (Pitchfork 2010).(9) Critic Stuart Berman particularly extols the guitar riff which follows the song’s opening drum break. He writes that “for exactly one second on ‘Only Shallow,’ My Bloody Valentine sound like any other rock band. But once [drummer] Colm Ó Cíosóig completes his brief introductory drum roll, My Bloody Valentine—and, arguably, guitar-based indie-rock music in general—were never quite the same again” (Pitchfork 2010).

Audio Example 2. My Bloody Valentine,

“Loveless,” 0:00–0:02

[5.2] Loveless is one of the most beloved and influential indie albums, but it was also one of the most agonizingly gestated rock albums ever made. The recording of the album took two years, eighteen studios, and approximately £250,000. It nearly bankrupted their record label, Creation Records, a British label famed for ’80s indie groups like the Jesus and Mary Chain, Felt, the Pastels, and Primal Scream.(10) Kevin Shields, the band’s guitarist, vocalist, and songwriter, obsessed over every single guitar sound. The opening chord (Audio Example 2) is suitably complex, an initial distorted explosion blasting into an upward thrust. Shields created this effect by performing the riff multiple times, layering each take on top of each other with additional feedback. Shields recalled that “I had two amps facing each other, with two different tremolos on them. And I sampled [the riff] and put it an octave higher on the sampler” (McGonigal 2007, 55–56). The technique of layering different takes of the same music was, of course, made famous during the Beatles’ “A Day in the Life,” where the London Symphony Orchestra played a crescendo a hundred times to create the orgiastic sweep of sound heard after verses two and three.

[5.3] If distilled to its notes, the riff outlines a simple

Figure 2. My Bloody Valentine, Loveless, cover

(click to enlarge)

Audio Example 3. My Bloody Valentine,

“To Here Knows When,” 0:18–0:32

[5.4] The sheer kinetic energy of this chord viscerally recalls the projective capabilities of musical motility. However, the question of exactly what self is being projected remains. The multitrack looping and feedback wash of the opening chord creates an inscrutable sound that swallows up pitch and rhythmic parameters. One overwhelmingly hears timbre over specific notes. The Fender Jazzmaster pictured on the cover, doused in purple and blurred almost beyond recognition, is an apt representation of the riff (see Figure 2). It is clear that this riff has different timbres than those in Example 1. Comparing the riff to mainstream guitar timbre via the four adjectives in paragraph 4.7 can illuminate specifically how the riff is differentiated and connect the sound with social distinction.

[5.5] The sound is full like the mainstream examples; it similarly projects a rash of overtones into the recording space. There is also a marked increase in distortion. The distortion is a product of careful processing and inserted feedback. The result transcends a simple power chord to something like a deep crunch turning into a wail. It is much louder and more aggressive than the mainstream examples, making it less digestible. The violent metaphors mentioned earlier assert the riff’s unsettling sublimity. The riff seems to indicate that it is foreground rather than background; it prepares the listener for the rest of the album, where the singers are barely heard amid the din of guitars (as in Audio Example 3, taken from “To Here Knows When”). Lastly, it is certainly not homogeneous with mainstream guitar distortion. Shields took care to produce a sound through an unusual process, and the metaphorical language in the reviews above strains to describe an ostensibly novel sound. It bears little resemblance to the mainstream examples aside from its basis in a distorted electric guitar.

[5.6] In summary, the sound is similarly full, it is more distorted, it is less digestible, and it is not homogeneous. These sonic aspects can relate to the album’s milieu of “shoegaze” music. Shoegaze was a British genre of indie music during the late 1980s and early 1990s featuring long, droning guitar sounds, inscrutable lyrics, and extended forms. The name came from a stereotypical performance style of hunching over and gazing at one’s shoes rather than facing the audience.(11) This performance posture presents a more restricted motility than the overpowering phallic posture of pop-metal groups, one which closes off associations with a dominating form of masculinity.

[5.7] Shoegaze bands performed an introverted masculinity that couched their individual identities, but the music they played was frequently louder than mainstream styles. My Bloody Valentine’s concerts at the time of Loveless featured an excruciating wall of distortion during the solo for their track “You Made Me Realize,” which lasted until audience members could no longer handle it (2007, 6–7).(12) While the performance posture removed individual identifying features, this at times literally indigestible wall of sound violently projected a discomfiting motility. It critiques the mainstream sound through sonic excess, thus offering a different (and not necessarily less dominating) form of masculinity. The opening riff of “Only Shallow” mimics the combination of restricted posture and sonic sublime, hiding the chord’s pitch characteristics behind a dense, inscrutable wash of heavy distortion.

Neutral Milk Hotel, “The King of Carrot Flowers, Part 1”

[6.1] Neutral Milk Hotel was composed of Jeff Mangum, the main singer-songwriter, and multi-instrumentalists Jeremy Barnes, Scott Spillane, and Julian Koster.(13) Their album In the Aeroplane over the Sea was recorded and produced by Robert Schneider in Denver, and was released by Merge Records in 1998. Though little known upon its release, the album’s critical reception has grown over the ensuing decade. Pitchfork named the album their fourth greatest of the 1990s, two spots behind Loveless (Pitchfork Staff 2003).(14) A 2008 poll of eMusic users even named it the greatest album of all time (eMusic 2008).(15)

[6.2] “The King of Carrot Flowers, Part 1” features an idiosyncratic instrumentation of vocals, acoustic guitar, bass, accordion, and zanzithophone, a MIDI saxophone manufactured during the mid-1990s. Mangum became fascinated with using unusual combinations of instruments for timbral interest through his passion for 1960s pop. He covered the Paris Sisters’ “I Love How You Love Me,” which was produced by Phil Spector, on his Live at Jittery Joe’s album.(16) The recording studio set up to record In the Aeroplane over the Sea was named “Pet Sounds Studios” in homage to the Beach Boys album. Robert Schneider stated that in producing the album he wanted to make “perfect psychedelic pop, a Revolver kind of album” (Cooper 2005, 54). These 1960s touchstones all feature an obsessive commitment to exploring unusual timbral palettes created from a wide range of instrumental forces through recording. By referencing these artists, Mangum indicates an intentional focus on the timbral possibilities of instrumental and production choices. Mangum highlighted the intentionality of the album’s musical production by declaring in an interview, “all of the recording is intended” (McGonigal 1998, 19).

[6.3] “The King of Carrot Flowers, Part 1” accumulates timbres throughout the piece, fitting Mark Spicer’s theory of cumulative form. Spicer defines cumulative form as a pop/rock form featuring a continuous instrumental build culminating in a final groove at its conclusion (Spicer 2004). The song, like Spicer’s examples, is recorded with extreme compression, creating an expansion of timbre rather than a crescendo.(17) However, “The King of Carrot Flowers, Part 1” departs from Spicer’s concept in one crucial way. Spicer theorizes that cumulative form usually begins with a striking or unusual timbre, with instruments more central to the song’s texture added over time. “The King of Carrot Flowers, Part 1” instead begins with guitar and voice, with ancillary instruments added throughout the song. Rather than the disorienting, oblique openings that Spicer discusses in, say, Radiohead’s “Packt Like Sardines in a Crushd Tin Box” or New Order’s “Blue Monday,” the song’s opening is profoundly orienting and warm.

Audio Example 4. Neutral Milk Hotel,

“The King of Carrot Flowers, Part 1,” 0:00–0:12

[6.4] “The King of Carrot Flowers, Part 1” begins with a strummed acoustic guitar miked closely and placed in stereo (see

Audio Example 4). Mangum plays a full six-string F major chord, then power chords for C and

Audio Example 5. Neutral Milk Hotel,

“The King of Carrot Flowers, Part 1,” 0:42–0:51

Audio Example 6. Neutral Milk Hotel,

“The King of Carrot Flowers, Part 1,” 1:26–1:35

[6.5] As the song progresses, new sounds emerge smoothly from earlier timbres, adroitly and subtly building from a simple, direct texture to a complex timbral world. At the end of the second verse, Mangum sustains the last word, “for,” as the accordion and bass enter (see Audio Example 5). The breathy timbre of the accordion seemingly morphs directly out of the deep, round vowel sound in Mangum’s exhalation. The reedy timbre and full voiced chords of the accordion richly fill the sound space. The long, regular chords emphasize the breathy push/pull effect of the accordion’s bellows. The bass underpinning unobtrusively extends the sonic range into a lower register. Before the final line of the last verse (Audio Example 6), the accordion moves to a suspension, creating a more dissonant harmony that thickens its resonance. It then resolves to a more pinched chord in a higher register that underpins the line “each one a little more.” Mangum’s voice likewise shifts to a higher register, opening up to a reedy, head voice on the words “than he.” This change in vocal production creates a strident timbre that enables Mangum to lunge for the climactic high F at the end of the line. The zanzithophone enters in conjunction with the registral change exhibited by the breathy instruments. Its shrill wind sound matches the new timbres of this section and accompanies the upward scalar figure that leads to the climax at the end of the line.

Figure 3. Neutral Milk Hotel, “The King of Carrot Flowers, Part 1,” tone color diagram

(click to enlarge)

[6.6] A comparison of “The King of Carrot Flowers, Part 1” to the mainstream guitar sounds of Examples 1a and 1b illuminates both how different this song sounds from the mainstream exemplars, but also how different its differentiation is from My Bloody Valentine. The sound is full, but not distorted. It is imminently digestible and warm, and the song evolves into a heterogeneous timbral tapestry, both within its given soundscape and as compared with mainstream expectations. Figure 3 maps the timbres in “The King of Carrot Flowers, Part 1.” The y-axis of the map represents the fixed volume, while the x-axis represents time. Within this stricture, new timbres are added, creating a more colorful overall sound. The diagram uses ruddy oranges and browns to represent the colors of the instruments. The color palette features hues that are warm and full. They are meant to subjectively evoke timbral color, rather than serve as one-to-one associations.(19) Their color differences are meant to imply comparison between different sounds. For example, the brighter orange used for the zanzithophone underscores the direct, pinched nature of its sound as compared with the more resonant, warmer brown used for the guitar. The gradients between colors represent the song’s careful timbral transitions.

[6.7] As the first song on the album, “The King of Carrot Flowers, Part 1” introduces the listener to the following tracks. Its additive textural transformations create the impression of a timbral progression, perhaps a sort of journey. The song’s lyrics appear to emplace a subject at the outset of such a journey by addressing him or her in its opening words, “When you were young.” The “you” might be heard as addressing the listener. The full, warm guitar timbres at the beginning further invite the listener, and the building timbral complexity entreats the listener to follow. It acts as a sonic analogue to the beginning of a story, with new characters creating complexity within a fixed linear temporal flow.

[6.8] Mangum, however, does not direct his lyrics exclusively towards the listener. The overall album centers on Mangum’s love for Anne Frank borne from reading The Diary of Anne Frank (McGonigal 1998, 21). Mangum became angered at the horror of a society that would enable her to die, and wished to bring her back to life. As he said in an interview, “[I] would go to bed every night and have dreams about having a time machine and somehow I'd have the ability to move through time and space freely, and save Anne Frank” (McGonigal 1998, 22).(20) The warm timbres, smooth transitions, and the “you” in this song can thus be seen as directed towards Anne Frank, to provide a haven to bring her back to life so that she may be loved.(21) The use of long, breathy timbres may thus act as aural resuscitation, trying to imbue her ghost with the breath of life.(22) Through this song, Mangum prepares a musical Ouija board to communicate with her ghost.

[6.9] In interviews, Mangum linked shock at Frank’s horrific death with distaste for mainstream culture and associations of this culture with aggressive masculinity. He stated his revulsion by claiming that, during his youth in Ruston, Louisiana, he “was surrounded by totally racist, sexist jocks. From an early age, all of us felt like we didn’t belong there. We all kind of saved ourselves from that place” (McGonigal 1998, 22). The use of a warm, yet clean acoustic guitar in “The King of Carrot Flowers, Part 1” manifests Mangum’s opposition by offering a timbral tableau differentiated from mainstream guitar sounds and their attendant stereotypes of politically backwards masculinity.(23) Musical motility is here used to resuscitate and embrace Anne Frank, to save her from the violence that cruelly took her life.

The Shins, Oh, Inverted World

[7.1] Both My Bloody Valentine’s “Only Shallow” and Neutral Milk Hotel’s “The King of Carrot Flowers, Part 1” demonstrate how timbre marks a move away from mainstream sound, albeit in nearly opposite ways. The Shins’ Oh, Inverted World presents a more complicated form of indie music differentiation, one premised on dissatisfaction with both a present mainstream and other indie genres. The Shins originated in home recordings made by singer and guitarist James Mercer apart from his then-current group, Flake Music. Flake Music was a noise rock band, a genre associated with improvisatory sounding, loud bursts of noise. Mercer became disenchanted with the lack of forethought and structure both in his music and in other noise rock bands. As he said in an interview, “if there's one criticism I have of the music that’s pretty common right now, it’s that no one seems to be trying to actually write songs, at least in the traditional sense. That's what we try to do” (Henningsen 2001).

[7.2] Mercer stereotyped—indeed, homogenized—contemporary music, both indie and mainstream, as unskilled. His form of differentiation was to create, as per a 2002 group biography, “an American Pop project based on that DIY ethic past generations have clung to” (The Shins 2002). This statement merges two styles generally seen as opposing: American pop music, seen as the product of the mainstream music industry, and do it yourself music, the product of amateurs rebelling against this very industry. In order to retain a sense of distance from contemporary mainstream music, Mercer, like Neutral Milk Hotel, was strongly influenced by a temporally distanced form of mainstream music, 1960s pop. British Invasion groups like the Beatles, Kinks, and Zombies were especially strong influences on the Shins because of their innovation within standard songwriting forms. For example, Mercer raved in one interview about the “perfect subtlety” of the transition between verse and chorus in the Beatles’ “Girl” (Nelson 2001). Mercer’s self-recording project turned into the Shins’ debut album, Oh, Inverted World, which was released in 2001 by Sub Pop Records.

Audio Example 7. The Shins,

“The Celibate Life,” 0:21–0:45

Audio Example 8. The Shins,

“One By One All Day,” 0:00–0:17

Audio Example 9. The Shins,

“New Slang,” 3:30–3:50

[7.3] In Oh, Inverted World, Mercer emulated British Invasion artists through harmonic, melodic, formal and lyrical features. However, timbre is deployed in the album in two interesting ways, which directly connect the album with its 1960s influences. First, Mercer utilizes timbre to highlight salient formal maneuverings. A subtle example of this is found in “The Celibate Life” (see Audio Example 7). A soft violin subtly enters as a background instrument in the first chorus. After the crescendo at the end of the solo, the violin transitions to choral aahs, which then transition back to the violin during the solo. Here the string and vocal timbres thicken the sound, providing a musical detail of “perfect subtlety” only heard through attentive listening. Mercer also features unusual intros and codas where songs morph out of, or into, unusual sounds. Two notable examples are the opening of “One By One All Day” (Audio Example 8) where a high-pitched electronic sound and percussive rumble herald a bright and clean Rickenbacker guitar and tom-heavy drum set, and “New Slang” (Audio Example 9) where the spare acoustic guitar texture fades out through an electronic upward glissandi mimicking a tape acceleration.(24)

Audio Example 10. The Shins,

“Girl Inform Me,” 0:00–0:25

Audio Example 11. The Shins,

“Pressed in a Book,” 1:05–1:27

[7.4] Second, Mercer’s songs mirror the comparatively restricted timbral world of 1960s pop through instrumental choices and softer dynamics. The opening of “Girl, Inform Me” exemplifies this sound (Audio Example 10). The song opens with voice and lead guitar pushed forward in the mix, with rhythm guitar in the background. Mercer sings very high in his range without using any vocal effects, creating a clean yet pinched timbre. The lead guitar rings bright and clean, also similar to the tone of the Byrds’ Rickenbacker guitars and mirroring the unaltered sound of the vocals. When the full band (bass, keyboard, and drums) enters on the second half of the verse, the volume unusually decreases. The instruments are all panned to both sides, creating a mono-like sound. The keyboard, which sounds like a late 1960s to early 70s Hammond organ, resonates above the rest of the band, and the use of ride cymbal creates a wash of high frequency. (25) Other songs on the album, such as “Girl on the Wing,” “Weird Divide,” and “Pressed in a Book” (Audio Example 11) feature similarly restricted timbral worlds.

[7.5] Oh, Inverted World offers a much less full sound than My Bloody Valentine, Neutral Milk Hotel, or the mainstream rock exemplars. Part of the reason is that Mercer began this project a relative amateur in self-recording, alluding in interviews to the rudimentary recording technology used to make Oh, Inverted World (Henningsen 2001). He did not have the recording resources of either Neutral Milk Hotel or My Bloody Valentine, instead relying on deft miking and volume control rather than compression to fill the sound space. By working under such limited constraints, Mercer foregrounds his amateurism through self-made, but lower, production qualities, hence adhering to the “DIY aesthetic.” Yet Mercer chooses instrumental timbres that come from 1960s records, such as a bright, clean Rickenbacker-esque guitar and the Hammond-like organ. The articulation of DIY production and 1960s pop is intelligible because 1960s music sounds lo-fi to a 21st-century listener given modern production innovations which allow for a much wider range of sounds. These sounds are less full, less distorted, but more digestible and heterogeneous than either mainstream rock or the loud, abrasive sounds frequently performed by noise rock groups like Mercer’s previous outfit. He would want to orient his recording capabilities toward the timbrally constricted sound, and thus increased songcraft, of 1960s pop.

[7.6] Mercer’s attention to musical details as derived from 1960s pop music, a genre firmly within the musical mainstream, complicates a strict separation between independent and mainstream. The Shins’ self-definition as an American pop band with a DIY aesthetic omits the word “indie,” and a biography on their website in 2009 claimed that the band aims to “bring indie pop into the mainstream” (The Shins 2009). This definition distinguishes them from the current mainstream by tacitly claiming indie pop’s difference, but does not differentiate them from all mainstream traditions, whether past or future. In Oh, Inverted World, 1960s pop styles provide an alternative from both current mainstream and alternative music because of their comparatively restricted motility and formal nuance.

Conclusion: Timbre, Pitch, and Identity

[8.1] Recent popular music theory continues to offer important findings that broaden scholarly discussion of the harmonic (Everett 2007, 2009; Biamonte 2010; Temperley 2011) and formal (Spicer 2004; Biamonte 2011) aspects of rock music. The October 2011 issue of this journal expanded on the complex function of form within musical analysis, addressing an important and problematic feature of popular music analysis. Though some essays in this issue briefly mention timbre (Osborn 2011 gives the most attention), they do not challenge the traditional theoretical conception that textual identity, premised on pitch and rhythm elements, correlates to generic, discursive, and political identity.

[8.2] The subjugated position of timbral analysis in contemporary music theory is demonstrated in an anecdote from Nadine Hubbs:

Following his discussion of the Nirvana song “Lithium,” Walter Everett was told by one audience member that all his talk of “notes” had been irrelevant, since the only thing of importance in Nirvana is the timbre of Kurt Cobain’s guitar. In later dialogue . . . Everett posed a rhetorical and illustrative question—roughly, “I wonder which performance my questioner would find closer to the heart of ‘Lithium’: playing its pitches and rhythms on a cheesy keyboard, or even on steel drums; or playing, say, ‘Baby I’m a-Want You’ on a heavily distorted Jagstang like Cobain’s? (Hubbs 2007, 231)

Everett’s question is true as phrased—we would understand the former as “Lithium.” However, textual identification does not necessarily correlate with social identity. Hearing “Lithium” through MIDI-produced sine waves removes the original’s angst and power. Analysis sans timbre would ignore how Cobain’s shifting guitar timbres project extramusical issues like masculinity, whiteness, and class anxieties.(26) Such a reductive analysis would provoke a critique like Frederic Lieberman’s response to Graeme Boone’s Schenkerian-flavored analysis of the Grateful Dead’s “Dark Star”: “This is the most etic analysis I’ve ever heard” (quoted in Boone 1997, 205).(27)

[8.3] John Covach has famously argued that theorists can focus on purely musical aspects without “necessarily adopt[ing] a sociological orientation” because social elements can be considered inessential to textual features supposedly more central to the ontology of a song (1997, 133). A phenomenological perspective based on Merleau-Ponty’s idea of motility, however, questions the existence of the “purely musical.” It asserts that embodiment and intentionality are always present in the production of sound, and that sounds are always projected within a social context. Moreover, the recuperation of adjectives as comparatively understood timbral descriptors from Casey’s theory of place questions the existence of the “pure description.” It asserts that sounds are created and described given subjective orientations within particular contexts, and that analysis can be sympathetic to the meaningfulness of a contextually defined adjective.

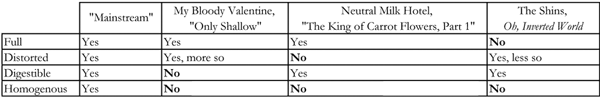

Figure 4. Comparison of timbral adjectives between My Bloody Valentine, Neutral Milk Hotel, and the Shins

(click to enlarge)

[8.4] By turning an ear toward timbre, analysts can instead adequately connect musical aspects with social politics. I have summarized the respective qualities of each artist’s timbres in Figure 4. Each artist offers a different form of timbral differentiation from the original mainstream sound described earlier. My Bloody Valentine’s “Only Shallow” is not digestible, Neutral Milk Hotel’s “The King of Carrot Flowers, Part 1” is not distorted, and the Shins’ Oh, Inverted World is not full. However, each artist offers a heterogeneous timbral palette connected with an increased sense of recording and songwriting craft which produces unusual sounds. This finding may lead one to theorize that, if anything, indie music is unified by a sense of timbral heterogeneity. The particular method of sonic differentiation in each song relates with a form of extramusical differentiation. The indigestibility of My Bloody Valentine’s riff relates to the combination of shoegaze music’s aggressive, painful sound assaults with restricted performance posture. The warmth of Neutral Milk Hotel’s timbres connect with lead singer Jeff Mangum’s love for Anne Frank. The restricted sound of the Shins creates a soundworld mimicking 1960s music different from his prior noise rock repertoire.

[8.5] Through these analyses, this paper argues that timbre is the primary musical parameter for comprehending strategies of differentiation omnipresent in indie music. Additionally, I demonstrate that timbre can be isolated and theorized from a phenomenological, contextual, and comparative perspective to articulate musical difference and extramusical differentiation. More broadly, attention to timbre can breach the disciplinary divide between culture- and music-based approaches, creating a methodology for popular music analysis more consonant with Anglo-American popular music practices without mystifying sonic construction. Rather than a popular music theory detached from social factors, a timbral focus can help unearth the identity politics embedded in the musical fabric of recorded sound.

David K. Blake

SUNY-Stony Brook

Department of Music

100 Nicolls Road

Stony Brook, NY 11794-5475

dkblake@ic.stonybrook.edu

Works Cited

Barthes, Roland. 1977. “The Grain of the Voice.” In Image Music Text. Trans. by Stephen Heath. 179–89. New York: Hill and Wang.

Bayton, Mavis. 1997. “Women and the Electric Guitar.” In Sexing the Groove: Popular Music and Gender, ed. Sheila Whiteley. 37–49. New York: Routledge, 1997.

Biamonte, Nicole. 2010. “Triadic Modal and Pentatonic Patterns in Rock Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 32, no. 2: 95–110.

http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.11.17.3/mto.11.17.3.biamonte.html.

—————. 2011. “Introduction.” Music Theory Online 17, no. 3.

http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.11.17.3/mto.11.17.3.biamonte.html.

Blake, David K. 2009. “Internet Music Criticism as Archive: Pitchfork Media and Neutral Milk Hotel’s In the Aeroplane over the Sea.” Paper delivered at the International Association for the Study of Popular Music–US Chapter, San Diego, CA.

Boone, Graeme M. 1997. “Tonal and Expressive Ambiguity in ‘Dark Star.’” In Understanding Rock: Essays in Musical Analysis, ed. John Covach and Graeme M. Boone. 171–210. New York: Oxford University Press.

Boulez, Pierre. 1987. “Timbre and Composition – Timbre and Language.” Trans. by R. Robertson. Contemporary Music Review 2, no. 1: 161–72.

Brackett, David. 1995. Interpreting Popular Music. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Casey, Edward. 1993. Getting Back Into Place: Toward a Renewed Understanding of the Place-World. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press.

Chou Wen-Chung. 1979. “Ionisation: The Function of Timbre in Its Formal and Temporal Organization.” In The New Worlds of Edgard Varese: A Symposium, ed. Sherman Van Solkema. 27–74. Brooklyn: Institute for Studies in American Music.

Cogan, Robert. 1969. “Toward a Theory of Timbre: Verbal Timbre and Musical Line in Purcell, Sessions, and Stravinsky.” Perspectives of New Music 8, no. 1: 75–81.

—————. 1985. New Images of Musical Sounds. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

—————. 1998. Music Seen, Music Heard: A Picture Book of Musical Design. Cambridge, MA: Publication Contact International.

Cogan, Robert and Pozzi Escot. 1976. Sonic Design: The Nature of Sound and Music. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Covach, John. 1997. “We Won’t Get Fooled Again: Rock Music and Musical Analysis.” In Theory Only 13, nos. 1–4: 119–41.

Cooper, Kim. 2005. In the Aeroplane over the Sea. New York: Continuum.

Cornicello, Anthony M. 2000. “Timbral Organization in Tristan Murail's ‘Désintégrations’ and ‘Rituals.’” Ph.D. diss, Brandeis University.

De Vale, Sue Carole. 1985. “Prolegomena to a Study of Harp and Voice Sounds in Uganda: A Graphic System for the Notation of Texture.” In Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology, Volume 5: Music of Africa, ed. J.H. Kwabena Nketia and Jacqueline Cogdell DjeDje. 250–81. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Dolan, Emily. 2010. “‘...This Little Ukulele Tells the Truth:’ Indie Pop and Kitsch Authenticity.” Popular Music 29, no. 3: 457–69.

eMusic. 2008. “The 100 Best Albums on eMusic.” eMusic.com. http://www.emusic.com/features/hub/bestalbums/index.html. Accessed February 25, 2012.

Erickson, Robert. 1975. Sound Structure in Music. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Everett, Walter, ed. 2007. Expression in Pop and Rock Music. 2nd rev. ed. New York: Routledge.

—————. 2009. The Foundations of Rock. New York: Oxford University Press.

Fales, Cornelia. 2002. “The Paradox of Timbre.” Ethnomusicology 46, no. 1: 56–95.

Feld, Steven. 1982. Sound and Sentiment: Birds, Weeping, Poetics, and Song in Kaluli Expression. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Fennelly. Brian. 1967. “A Descriptive Language for the Analysis of Electronic Music.” Perspectives of New Music 6, no. 1: 79–95.

Foucault, Michel. 1994. The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences. New York: Vintage.

Grossberg, Lawrence. 1986. “On Postmodernism and Articulation: An Interview with Stuart Hall.” Journal of Communication Inquiry 10, no. 2: 45–60.

Guck, Marion A. 1981. “Musical Images as Musical Thoughts: The Contribution of Metaphor to Analysis.” In Theory Only 5, no. 5: 29–43.

—————. 1997. “Two Types of Metaphoric Transference.” In Music and Meaning, ed. Jennifer Robinson. 201–12. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Headlam, Dave. 1997. “Blues Transformations in the Music of Cream.” In Understanding Rock: Essays in Musical Analysis, ed. John Covach and Graeme M. Boone, 59–92. New York: Oxford University Press.

Henningsen, Michael. 2001. “Oh Inverted World: The Shins Prepare to Turn the Music World Upside Down,” Alibi News 10, no. 25. http://www.alibi.com/alibi/2001-06-21/feature_section.html. Accessed February 26, 2012.

Hesmondhalgh, David. 1999. “Indie: The Institutional Politics and Aesthetics of a Popular Music Genre.” Cultural Studies 13, no. 1: 34–61.

Hibbert, Ryan. 2005. “What is Indie Rock?” Popular Music and Society 28, no. 1: 55–77.

Hubbs, Nadine. 2007. “The Imagination of Pop-Rock Criticism.” In Expression in Pop-Rock Music: A Collection of Critical and Analytical Essays, ed. Walter Everett. 2nd rev. ed., 217–39. New York: Routledge.

Ihde, Don. 2007. Listening and Voice: Phenomenologies of Sound. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press.

Kassler, Jamie C., ed. 1991. Metaphor: A Musical Dimension. Sydney: Currency Press.

Korner, Anthony. 1986. “Aurora Musicalis.” Artforum 24, no. 10: 76–79.

Lakoff, George and Mark Johnson. 1980. Metaphors We Live By. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Latartara, John. 2008. “Machaut's Monophonic Virelai ‘Tuit mi penser’: Intersections of Language Sound, Pitch Space, Performance, and Meaning.” Journal of Musicological Research 27, no. 3: 226–53.

Latartara, John and Michael Gardiner. 2007. “Analysis, Performance, and Images of Musical Sound: Surfaces, Cyclical Relationships, and the Musical Work.” Current Musicology 84: 53–78.

Laurin, Hélène. 2009. “The Girl Is a Boy Is a Girl: Gender Representations in the Gizzy Guitar 2005 Air Guitar Competition.” Journal of Popular Music Studies 21, no. 3: 284–303.

Lee, Stephen. 1995. “Re-Examining the Concept of the ‘Independent’ Record Company: The Case of Wax Trax! Records.” Popular Music 14, no. 1: 13–31.

McDonald, Chris. 2000. “Exploring Modal Subversions in Alternative Music.” Popular Music 19, no. 3: 355–63.

McGonigal, Mike. 1998. “Dropping In at the Neutral Milk Hotel.” Puncture 41: 19–22, 55.

—————. 2007. Loveless. New York: Continuum.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. 1981. Phenomenology of Perception. Trans. by Colin Smith. Atlantic Highlands, NJ: Humanities Press.

Millard, André, and Rebecca McSwain. 2004. “The Guitar Hero.” In The Electric Guitar: A History of an American Icon, ed. André Millard, 143–62. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Moore, Allan. 1992. “Patterns of Harmony.” Popular Music 11, no. 1: 73–106.

Nelson, Chris. 2001. “The Shins Kick it Old School with Kinks-y Pop.” Sonicnet.com. http://web. archive.org/web/20010713230224/www.sonicnet.com/news/story.jhtml?id=1444725. Accessed February 20, 2012.

Newman, Michael Z. 2009. “Indie Culture: In Pursuit of the Authentic Autonomous Alternative.” Cinema Journal 48, no. 3: 16–34.

Olwage, Grant. 2004. “The Class and Colour of Tone: An Essay on the Social History of Vocal Timbre.” Ethnomusicology Forum 13, no. 2: 203–26.

Osborn, Brad. 2011. “Understanding Through-Composition in Post-Rock, Math-Metal, and other Post-Millennial Rock Genres.” Music Theory Online 17, no. 3. http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.11.17.3/mto.11.17.3.osborn.html.

Pitchfork. 2010. “The Top 200 Tracks of the 1990s: 20–01.” Pitchfork.com. http://www.pitchfork.com/features/staff-lists/7853-the-top-200-tracks-of-the-1990s-20-01/2/. Accessed February 27, 2012.

Pitchfork Staff. 2003. “Top 100 Albums of the 1990s.” Pitchfork.com. http://www.pitchfork.com/ features/staff-lists/5923-top-100-albums-of-the-1990s/10/. Accessed February 27, 2012.

Schaeffer, Pierre. 1966. Traité des objets musicaux. Paris: Le Seuil.

Schreiber, Ryan. 1999. “Top 100 Albums of the ‘90s.” Pitchfork.com. http://pitchforkmedia.com/top/90s/index10.shtml. Accessed February 27, 2012.

Shepherd, John. 1987. “Music and Male Hegemony.” In Music and Society: The Politics of Composition, Performance, and Reception, ed. Richard Leppert and Susan McClary, 151–72. New York: Cambridge University Press.

The Shins. 2002. “The Shins—An American Pop Combo, Now With More Sub Pop.” The Shins.com. http://www.artisdead.net/theshins/main.html. Accessed February 20, 2012.

—————. 2009. “Biography.” www.theshins.com. Accessed May 16, 2009.

Slawson, Wayne. 1981. “The Color of Sound: A Theoretical Study in Musical Timbre.” Music Theory Spectrum 3: 132–41.

—————. 1985. Sound Color. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Spicer, Mark. 2004. “(Ac)cumulative Form in Pop-Rock Music.” Twentieth-century Music 1, no. 1: 29–64.

Spitzer, Michael. 2004. Metaphor and Musical Thought. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Sugarman, Jane C. 1997. Engendering Song: Singing and Subjectivity at Prespa Albanian Weddings. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.11.17.1/mto.11.17.1.temperley.html

Temperley, David. 2011. “The Cadential IV in Rock.” Music Theory Online 17, no. 1.

http://www.mtosmt.org/issues/mto.11.17.1/mto.11.17.1.temperley.html

Thornton, Sarah. 1996. Club Cultures: Music, Media and Subcultural Capital. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press.

Turino, Thomas. 1993. Moving Away from Silence: Music of the Peruvian Altiplano and the Experience of Urban Migration. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Waksman, Steve. 1999. Instruments of Desire: The Electric Guitar and the Shaping of Musical Experience. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Walser, Robert. 1993. Running with the Devil: Power, Gender, and Madness in Heavy Metal Music. Hanover, NH: Wesleyan University Press.

Warner, Timothy. 2009. “Approaches to Analysing Recordings of Popular Music.” In The Ashgate Research Companion to Popular Musicology, ed. Derek B. Scott, 131–45. Burlington, VT: Ashgate.

Young, Iris Marion. 2005. “Throwing Like a Girl: A Phenomenology of Feminine Body Comportment, Motility, and Spatiality.” In On Female Body Experience: “Throwing Like a Girl” and Other Essays, 27–45. New York: Oxford University Press.

Footnotes

1. Earlier versions of this article were delivered as two colloquia at SUNY-Stony Brook in March 2010, one for the Department of Music, and one as part of the Comparative Literature and Cultural Studies Graduate Colloquium Series. I wish to thank Judith Lochhead, Peter Winkler, Benjamin Steege, Aaron Hayes, Nicholas Tochka, Bethany Cencer, Andrew Eisenberg, Katherine Kaiser, Brianna Martino, and the journal’s anonymous referees for their helpful comments. Thanks to Philip Appleby for creating Figures 1 and 3.

Return to text

2. McDonald’s article briefly discusses the verse of “Only Shallow,” which features a I–

Return to text

3. Rebecca Leydon’s contribution to this volume engages the physiological and perceptual aspects of Fales’s paradox, especially her theory of “perceptuality.”

Return to text

4. Of course, numerous theorists, notably Guck (1981, 1997), Kassler (1991) and Spitzer (2004) posit that metaphor is intrinsic to musical description. Spitzer is a musicologist, but his study discusses the role of metaphor in Schenker and Meyer. Lakoff and Johnson (1980) assert more generally that metaphor underpins discursive meaning.

Return to text

5. The American Standards Association is the former name of the American National Standards Institute, an agency tasked with maintaining definitions of measurement standards for industrial and governmental purposes.

Return to text

6. Slawson uses “sound color” rather than “timbre.” However, I believe that the meanings of Slawson’s “sound color” and Brackett’s “timbre” are similar.

Return to text

7. Here I use “articulation” in Stuart Hall’s sense of a contingent yet meaningful linkage (Grossberg 1986).

Return to text

8. Shepherd (1987), following from Young (2005), connects mainstream popular music with strategies of male hegemony.

Return to text

9. Pitchfork’s album list ranked Radiohead’s OK Computer the greatest album of the 1990s. Pitchfork’s first Top 100 Albums of the 1990s list, compiled in October 1999, ranked Loveless the best album of the decade (Schreiber 1999).

Return to text

10. Kevin Shields has disputed this claim, stating that most of the album’s financial backing came from the group itself and that the record label’s fiscal woes came from founder Alan McGee’s drug issues. The mutual enmity between band and record label does little to clarify the situation.

Return to text

11. My Bloody Valentine is unquestionably the most famous shoegaze group, but other well-known artists include Ride and Slowdive.

Return to text

12. Mike McGonigal recalls this moment in a My Bloody Valentine concert he attended in 1992: “Here, tonight, the group has far more power. . . . And they are using it, all of it. . . . I’m smack in the middle of a large, confused crowd. People are freaking the fuck out from the noise, making for the exits or doing that swarm-dance version of slam-dancing that larger venues and alternative rock bands both tend to coax from younger audiences. Lots of these kids look really young, and do not look happy. I feel like maybe I could be sick, for real, so I step back from the swirl of backward baseball caps, my pulse quickening. I can imagine this is all coming across as hyper-hyperbolic, but the sounds feel like they are hitting me, especially in the stomach” (2007, 6).

Return to text

13. The question of tense for this group’s existence is problematic. The band hasn’t played since 1998, and Mangum himself became quite reclusive, granting only one interview during the first decade of the 2000s. Since 2010, however, Mangum has begun playing live shows again, reopening the possibility of a Neutral Milk Hotel reunion.

Return to text

14. The same Pitchfork list that named “Only Shallow” the sixth best song of the 2000s listed another song on In the Aeroplane over the Sea, “Holland, 1945,” the seventh best of the decade (Pitchfork 2010).

Return to text

15. eMusic is a digital music downloads store similar to the iTunes store. The choice of albums on the poll was limited to those then available on eMusic’s website, which covered a fairly wide swath of indie, funk, jazz, and classical. Ironically, the poll is no longer active on eMusic’s website after a deal with Sony and subsequent reformatting of their price structure caused many indie labels, including Merge, to withdraw their music from the website in protest.

Return to text

16. Mangum’s performance was solely voice and guitar. Other bands associated with Neutral Milk Hotel through the Elephant 6 Collective were more directly influenced by psychedelic pop. For examples, see Olivia Tremor Control, Music from the Unrealized Film Script: Dusk at Cubist Castle; The Minders, Hooray for Tuesday; The Apples in Stereo (led by Robert Schneider), Her Wallpaper Reverie and Tone Soul Evolution; and Of Montreal, The Gay Parade.

Return to text

17. Compression is a technique that reduces volume contrasts in order to constantly fill the available recording volume. Compression involves lowering the overall volume of a recorded sound wave, thereby reducing volume range, and then increasing volume back up to the digital distortion threshold.

Return to text

18. Thanks to Thomas Kenny for explaining Mangum’s guitar technique. The slight motion on the C chord is the striking of the open high E string upon removing the hand. The style of playing an acoustic guitar like an electric guitar may be why Kim Cooper claims that the opening is the “channeling of punk energy” (2005, 68). However, I think the breadth of the guitar’s resonance outweighs the guitar attacks, creating a comfortable rather than aggressive sound.

Return to text

19. The use of brown and orange, however, does evoke the sepia-toned photographs featured in the album and on the CD cover, though that association reflects my own synaesthetic tendencies rather than an objective association.

Return to text

20. After stating this, Mangum adds, “Do you think that’s strange,” underscoring the naked honesty and uncertainty of his emotional attachment to Frank.

Return to text

21. Though I have suggested the song’s subject is either the listener or Anne Frank, I would caution against a too-literal reading of this song’s lyrics with them in mind. Neutral Milk Hotel’s lyrics occasionally veer towards surrealistic imagery. (The end of “Two Headed Boy, Part 2,” where Mangum sings “she will feed you tomatoes and radio wire,” exemplifies Mangum’s poignant surrealism.” The explicitly sexual lines “as we would lay and learn what each other’s bodies were for” and “this is the room one afternoon I knew I could love you/and from above you how I sank into your soul/into that secret place where no one dares to go” may not necessarily imply a pedophilic fantasy toward Anne Frank. The use of “holy rattlesnakes” in the first verse also suggests an ecstatic surrealistic lyrical tableau.

Return to text

22. Mangum addresses Frank in other songs on the album through lyrics, such as “Ghost,” “In the Aeroplane over the Sea,” and “Holland, 1945.” In addition, “In the Aeroplane over the Sea” and “Two-Headed Boy, Part 2” feature ethereal timbres—musical saw and shortwave radio feedback—which also directly invoke Frank’s specter (Blake 2009).

Return to text

23. In the Aeroplane over the Sea tends to feature one of two guitar sounds; either a warm acoustic guitar as in “The King of Carrot Flowers Part 1” and “Two-Headed Boy,” or a overdriven distorted guitar as in “The King of Carrot Flowers Parts 2 & 3” and “Holland, 1945.” The overdriven guitar sounds are actually smoothened from Neutral Milk Hotel’s previous album, On Avery Island. See “Song Against Sex” or “Where You’ll Find Me Now.”

Return to text

24. The clean Rickenbacker guitar sound is reminiscent of the Byrds; see especially “Mr. Tambourine Man” from Mr. Tambourine Man (1965).

Return to text

25. The Hammond organ-like keyboard also takes the solo. This combined with the restricted volume is reminiscent of the Zombies, whose first three singles, “She’s Not There,” “Woman,” and “Tell Her No,” each feature similar keyboard solos.

Return to text

26. From a more formal perspective, it would miss the role of guitar distortion and vocal manipulation in accentuating verse/chorus structure.

Return to text

27. Grateful Dead keyboardist Tom Constanten’s response on the same page offered a similar sentiment: “The paper sounds like a weather report in French, delivered perfectly by someone who doesn’t speak a word of the language. While the points made are all true, the spirit of the paper has nothing to do with the spirit in which the music was made.”

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2012 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Michael McClimon, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits: