Review of Suzannah Clark, Analyzing Schubert (Cambridge University Press, 2011)

Kristina Muxfeldt

KEYWORDS: Franz Schubert, music analysis, harmony, reception history, song

Copyright © 2012 Society for Music Theory

[1] The genial discussions of analytic tradition and Franz Schubert’s music in Suzannah Clark’s Analyzing Schubert retain some of the flavor of a lively graduate seminar in comparative analysis, for which her book might well provide a foundation, perhaps in conjunction with another recent volume that places similar emphasis on the pedagogical benefits of comparative study, David Damschroder’s Harmony in Schubert (2010). Each chapter reviews and critiques scholarship around a few pieces or an issue, spotlighting the insights gained or shortcomings and blind spots in different approaches (Schenkerian, neo-Riemannian, sonata theoretical, or even multiple Schenkerian readings of the same passage). The thought is also to pinpoint aurally salient features that go unaddressed, and to imagine new analytical lenses with which to survey Schubert’s tonal landscapes. (Clark does not say so but her focus is nearly exclusively on ways of construing pitch relations.) Promising initiatives towards a “distinctly Schubertian paradigm” for analysis (270) are sketched, astute criticisms offered, and personal reactions to current work in the field freely shared: dozens of colleagues may be pleased to discover their work addressed.

[2] The book is divided into four chapters, three of them dedicated to specific analytical issues, while an initial chapter

takes up themes that run throughout nineteenth-century commentary on Schubert’s creative process. Here Clark

appears determined once and for all to debunk those appeals to clairvoyance and somnambulism that still delighted Victorian critics but are of little help to the modern analyst. Chapter 2 concerns mainly songs beginning and ending in different tonal regions, the subject of several recent studies, while chapter 3 looks at lyrical passages in the instrumental music often explained as “digressions.” Chapter 4 examines the various Stufen Schubert found to create a symmetrical balance between sonata expositions and recapitulations, relating this to Schenker’s “sacred triangle” and his early theoretical position that, in Clark’s words, “a range of keys may substitute for the so-called natural or conventional keys of the dominant and relative major in secondary themes

[3] As outlined briefly above, the opening chapter lays out how Johann Michael Vogl’s characterization of Schubert’s songs as the products of a “musical clairvoyance” gradually took on mythic status after Victorian-era Schubertians embraced and elaborated this picture even more eagerly than had the composer’s acquaintances. Since appeals to supernatural states or a divine hand could mask the learning and effort that went into Schubert’s composing, this may have forestalled close analytic engagements with his music. Clark thankfully also presents the contrasting perspectives of Josef von Spaun and Josef Hüttenbrenner, both quick to contest any suggestion that Schubert was not in full command of his powers. And yet: must “clairvoyance” (clear vision) and professional expertise necessarily be at odds? The small glimpses some of his friends may have caught of Schubert’s intense concentration, his flashes of poetic insight, or the remarkable pace of his productivity, no doubt left a memorable impression. Why, I wonder, did terms like clairvoyance and somnambulism come to Vogl’s mind at all, and why did these metaphors ring true to so many of his contemporaries (including Spaun)? Thought-provoking in this connection is Schubert’s musing in a lost notebook from March 1824: “Understanding [Verstand] is nothing more than an analyzed belief” (Deutsch 1996, 223; 1947, 337). More directly to the point is his moving account of a September 1825 visit to the grave of Michael Haydn, whose “calm and clear-headed” spirit he summoned, wishful that some of it might rub off (Deutsch 1996, 314; 1947, 458).

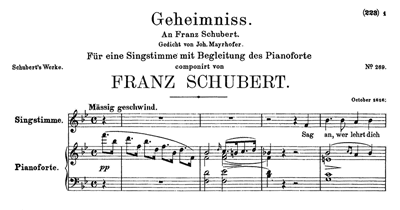

Example 1. Schubert, “Geheimnis” (Secret), D. 491

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[4] Clark prefers to picture an expertly self-taught Schubert, deliberate, fully aware, even methodical in his mastery. This sensibly chosen lens overcorrects, however, when she searches for evidence that Schubert would have resisted Vogl’s classical creation-trope. (“Speak through me” the Homeric bard calls to the muses before he spins a new tale from his storehouse of remembered plots.) Clark lingers over the 1816 song “Geheimnis” (Secret), D. 491, on a poem by Johann Mayrhofer addressed to the composer: “Sag an, wer lehrt dich Lieder?“ Who teaches you to make songs that transform our dreary present into sunshine, the poet asks. Example 1 gives the AGA score of the song with bar numbers added. The piano introduction depicts inspiration wafting down from on high, but John Reed finds “a conventional touch in the writing on the last page” (1997, 239). This leads Clark to ask whether Schubert’s setting might be ironic. “What if Schubert is portraying his music as least inspired when tapped straight from a muse?” she wonders (18). That way he would not have been complicit in the myth-making. (Schubert and Vogl hadn’t yet met in any case.)

[5] The song “contains a number of characteristic modulations. Two are hexatonic; one of which is masterful in execution, the other awkward. The masterful one comes amidst a more poetic aspect of the text about an old man crowned with reeds who pours out his urn and water flowing in a meadow” (18). By “more poetic” Clark must mean the mythological allusion that connects these two images: “You do not glimpse the old man who pours out his urn [Aquarius, a constellation];

[you see] only the water as it flows through the meadows.” The smooth harmonic transformation from

[6] I dwell on this example because it illustrates a tendency I found frustrating in Clark’s otherwise admirably readable and engaging book. We gladly follow her lively discussions of published analyses that make up the book’s substance because she promises to identify “hermeneutic windows” (in Lawrence Kramer’s terminology), views that earlier perspectives have obscured. Yet when Clark locates such a window she can seem reluctant to open it very far, preferring to make only hasty notations—often astute—before resuming her trek through the landscape of Schubert scholarship. It is a great virtue of her book, of course, that she charts so many places to which we might profitably return.

[7] A sustained discussion of analyses by Harald Krebs (1980, 1981), Thomas Denny (1989), and Michael Siciliano (2005) of the song “Trost,” D. 523, again stirs expectation by noting that these critics all left away consideration of the poem in their accounts of the novel musical syntax. Clark herself, however, ventures but one terse sentence on the subject. (“The strophic nature of the poem together with the pattern of repeated lines produce the structure of repeated elements (or repetends) abca bdeb cfgc abca, which provides a strong argument for the cyclic nature of this song” (103).) The phenomenological experience of “Trost” (consolation) is especially rich because its four short musical phrases (their respective third-related harmonies all linked by a common tone

Nimmer lange weil ich hier,

Komme bald hinauf zu dir.

Tief und still fühl ich’s in mir

[dass] nimmer lange weil ich hier.

Nimmer lange weil ich hier,Komme bald hinauf zu dir,

[denn] Schmerzen Qualen für und für

wüten in dem Busen mir:

Komme bald hinauf zu dir.Komme bald hinauf zu dir.

Komme bald hinauf zu dir:Tief und still fühl ich’s in mir:

eines heissen Dranges Gier

zehrt die Flamm’ im Innern hier—

Tief und still fühl ich’s in mir.Tief und still fühl ich’s in mir.

Tief und still fühl ich’s in mirNimmer lange weil ich hier,

Komme bald hinauf zu dir.

Tief und still fühl ich’s in mir:

Nimmer lange weil ich hier.[dass] Nimmer lange weil ich hier.

[8] Clark’s discussion of reviews by the conservative early nineteenth-century critic Gottfried Wilhelm Fink yields the fruitful observation that although he complained frequently about Schubert’s modulations, he was more bothered by Schubert’s manner of reaching keys than by their distance from one another. One example is a passage in the captivating song “Selige Welt,” D. 743, shown in Example 2, where Schubert cycles rapidly through

[9] In “Orest auf Tauris,” D. 548, a song that begins in

Example 2. Schubert, “Selige Welt”, D. 406

(click to enlarge and see the rest)

[10] Clark’s interest in the middle section of “Selige Welt” (Example 2), unsurprisingly is the

[11] Such common tone “threads” may appear in constructions of tonal disorientation or focus, stability or slippage, kaleidoscopic juxtapositions or smooth transitions—the stuff of musical storytelling. Large-scale tonal balancing likewise combines with melodic shape, range, acoustical resonance, and certainly with long-range metrical forces to create compelling emotional trajectories. (Consider how Mozart, in the quartet in Idomeneo, another

Kristina Muxfeldt

Indiana University

Jacobs School of Music

1201 E. 3rd Street

Bloomington, IN 47405

kmuxfeld@indiana.edu

Works Cited

Damschroder, David. 2010. Harmony in Schubert. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Denny, Thomas. 1989. “Directional Tonality in Schubert’s Lieder.” In Franz Schubert—Der Fortschrittliche? Analysen, Perspektiven, Fakten, edited by Erich Wolfgang Partsch, 37–53. Tutzing: Hans Schneider.

Deutsch, Otto Erich. 1947. Schubert: A Documentary Biography. Translated by Eric Blom. London: J. M. Dent.

—————. 1996. Schubert: die Dokumente seines Lebens. Wiesbaden: Breitkopf & Härtel.

Krebs, Harald. 1980. “Third Relation and Dominant in Late 18th- and Early 19th-Century Music.” Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University.

—————. 1981. “Alternatives to Monotonality in Early Nineteenth-Century Music.” Journal of Music Theory 25, no. 1: 1–16.

Reed, John. 1997. The Schubert Song Companion. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Schubert, Franz. 1964–. Neue Ausgabe sämtlicher Werke, Series 4, vol. 11. Kassel: Bärenreiter Verlag.

Siciliano, Michael. 2005. “Two Neo-Riemannian Analyses.” College Music Symposium 45: 81–107.

Footnotes

1. Just how Clark uses “hexatonic” I’m not sure because only this one progression aligns with Cohn’s network of major thirds. The harmonic changes in the song are

Return to text

2. Incidentally, the Kritischer Bericht (series 4, vol. 11) of the New Schubert Edition, whose helpful score layout Clark has borrowed, contains intriguing speculation on the poem’s sources and authorship (Schubert?).

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2012 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Carmel Raz, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits: