Review of Godfried Toussaint, The Geometry of Musical Rhythm: What Makes a “Good” Rhythm Good? (CRC Press, 2013)

Mark Gotham

KEYWORDS: Rhythm, world rhythms, mathematical modelling, geometry.

Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory

[1] The Geometry of Musical Rhythm is Godfried Toussaint’s first monograph offering to the musicological community. Mathematician-cum-musicologists are increasingly common in music theory, but Toussaint is a singular case. With expertise covering information theory, electrical engineering, and computer science, and interests spanning everything from African drumming to evolutionary biology, his stated aim to “create an interdisciplinary academic bridge” between these fields amounts to a considerable undertaking.

[2] Toussaint has found an eminently suitable subject for that goal in the mathematical modelling of musical rhythm as expressed in symbolic form. In turn, the musicological community will discover in Toussaint’s work an array of current and historical thought on geometric models, and a substantial contribution to a field that still lags behind the more developed theoretical literature on pitch, notwithstanding a vigorous revival of interest in rhythm and meter during the later twentieth century.(1)

[3] Toussaint’s list of personal acknowledgments provides general insight into the position of the book within the musicological landscape,(2) while for many readers, the modelling will most readily bring to mind the work of other mathematicians to have graced the field. Jeff Pressing ticks both boxes. His iconic 1983 article on isomorphisms between scales and rhythms from around the world is perhaps the most direct precursor to Toussaint’s volume in both tone and content, for its combination of mathematical relations with ethnographic enquiry. Mathematical formalizations of musical space, such as those in Lewin 1987(3) and Polansky 1996 are relevant precedents, though Toussaint’s project differs in its aims and target audiences. Some of the relationships between rhythmic patterns have been explored in recent subfields of music theory (such as beat-class modulation in Roeder 2003 and Cohn 1992 after Babbitt 1962), and others parallel models from the pitch literature (such as Clough and Douthett’s 1991 formalization of maximal evenness).

[4] In many senses, this is a timely book. It is interdisciplinary (a quality openly promoted by the academy today), is concerned with an under-represented musical parameter (Toussaint is suitably condemnatory of the “long-standing bias against rhythm as the fundamental property of music” (305)), and concomitantly focuses on under-represented repertoires. It is also made available to a wide readership, as Toussaint balances the range of technical content with a writing style that remains suitable to lay readers. No knowledge of music or mathematics is assumed, although italicized terms are occasionally introduced without definition and others are used in questionable ways.(4)

[5] The disposition of the book reflects aspects of its background. Partly owing to the range of fields and topics drawn upon, the 363-page book is divided into many short chapters. Each introduces a different perspective on the same recurring questions (including the eponymous “What makes a ‘good’ rhythm good”), and the same “illustrious” rhythms, democratically taken to be “good” on the strength of their preponderant use throughout the world and its history.(5) Chapter 37 reprises many of the relations used, though it serves more as a summary than as the climax of an argument.

[6] In short, this book does not read as a work of traditional musicology. That is as true of the content and language as it is of the shape and organization. Tellingly, the publisher focuses on “scientific, technical, and medical content,” and lists this work under “General Mathematics and Introductory Mathematics.” However, “General Mathematics and Introductory Mathematics” is exactly what certain branches of musicology need, especially when that introduction includes relevant findings from such a wide range of unfamiliar disciplines. For instance, a principal motivation for Toussaint in writing this book has been to evangelize the merits and utility of phylogenetic analysis, a topic which originated in the field of evolutionary biology: hardly the most immediate cousin of musicology.

[7] However, the course of true interdisciplinarity never did run smooth. The main ontological burden for a project like this is to defend the validity of the proposed mathematics as an explanation of musical phenomena. This must amount to more than self-evident proofs of structural properties in musical systems and it is an issue of more pressing, continuing relevance than can be neatly disposed of in prefatory remarks. Psychology earns several mentions in the book, though it explicitly plays second fiddle to the symbolic, written score here.(6) Toussaint occasionally incorporates psychological phenomena, as in the mention of the perceptual present as a justification for the validity of the interval vector (after Pearsall 1997) but the omission is problematic in other places.

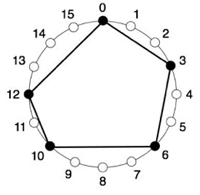

Figure 1. The clave son represented on a circular timeline

(click to enlarge)

[8] It has an especially uneasy relationship with the visual representation on which the project depends. Rhythms are frequently displayed in the form of a circular timeline, measured out with dots at equal intervals to represent the pulse, among which black (filled-in) dots represent note onsets. For instance, Figure 1 represents the ‘clave son’: a 16-pulse rhythm with 5 onsets at positions 0, 3, 6, 10, and 12. In the text, this is usually referred to by the unit durations between onsets, here [3-3-4-2-4]. This circle is the principal mathematical space in which Toussaint’s geometric properties and relationships operate.

[9] This representation is not Toussaint’s invention, but it leads to some quintessentially spatial relations that do not necessarily analogize well to temporal patterns. In defense of the palindrome property, for instance, Toussaint boasts that the geometric representation “highlights the ease with which humans perceive spatial symmetry” (34). However, he also acknowledges (by quotation) that temporal symmetry is “extremely difficult to perceive” (Handel 2006, 188). This undermines the validity of constructing a theoretical framework for its analysis, especially one employing the spatial analogy. Of course, musicians do talk of retrogrades, but with caution, and in limited circumstances.

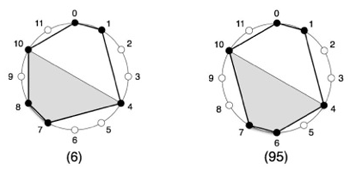

Figure 2. Partial Mirror Symmetry of a rhythm

(click to enlarge)

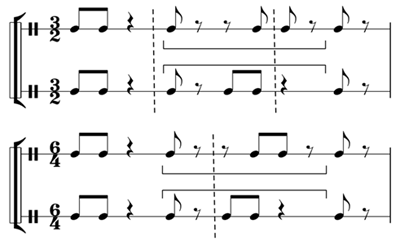

Figure 3. The equivalent rhythms in musical notation

(click to enlarge)

[10] The relation concerning mirror symmetry of part of a rhythm is particularly questionable. Consider the two rhythms in Figure 2: identical but for the onsets at positions 6, 7, and 8. Several of Toussaint’s relationships would account for this similarity. For instance, it would be easy to follow and credit an ‘edit distance’ approach concerning the number of changes necessary to transform one rhythm into the other. Here, that would be a question of moving either the two onset pair by a distance of one step together, or one onset by a distance of two steps (between pulse positions 6 and 8).(7) It is much harder to defend the relationship actually proposed: one based on a symmetrical equivalence between the two forms that applies to only the shaded half of the rhythmic timeline, an area which commences and concludes at metrically-weak positions. Figure 3 re-expresses this relationship in musical notation.(8) The brackets indicate the region in which symmetry is discussed, and dashed, vertical lines clarify the primary metrical division of each version.

[11] One defense of the representational, mathematical approach is that objective measures and definitions are preferred over subjective ones. Although this aim is laudable, the measures themselves need to reflect the complexity of the terms in question if they are to offer a substantial alternative. Toussaint disapproves of the “vague” definitions of syncopation (2, after Berry 1976), but his alternative, quantified measure of “off-beatness” (101) is not a satisfactory replacement from a musical perspective. This precision is also at odds with the generously broad definitions that Toussaint reaches in the opening chapters while picking through various of the thorny issues that recur in rhythm and meter research.

[12] In many other respects, Toussaint shines as a conscientious polymath, especially in the range of topics engaged and the extensive reference to rhythms from across the world. That geographical plurality frequently extends to an engagement with culture-specific performance practice and ideological sensibilities. The book also includes many drawings of musical instruments, the construction and playing technique of which contribute to Toussaint’s arguments. This is often illuminating, though in places it is opaque. For instance, Toussaint analogizes “hourglass” rhythms (those with shortest values in the middle of the timeline, such as [4-3-2-3-4]) to a Chinese drum of the same shape for no obvious reason (233–35).

[13] Toussaint’s approach to other repertorial areas, such as Western vernacular, and even Western art music, is rather more sporadic. Certain of Steve Reich’s works earn several mentions (though the classification of Reich’s music in relation to Western versus African styles is debatable) and the reader is introduced to a number of Anglo-American bands they may not otherwise know, but one gets no real sense of the rarity or significance of those observations. This is not necessarily a problem per se, but the isolated references do little to advance any ongoing argument, such as the claim of universality which appears to be the motivation for their inclusion. This is one area which would benefit from a corpus study, perhaps one based on the sample of rhythms in popular Western music extracted from the internet by Mauch and Dixon (2012).

[14] Some obvious references to Western art music are either missed or avoided. For instance, in the discussion of “deep rhythms” after Paul Erdös, a [2-1-1-2] rhythm that meets the relevant structural criteria is discussed. Toussaint proceeds to cite examples of this rhythm from around the world without mentioning that it is also the simple hemiola, common to the point of cliché in cadences of the Baroque era. That omission is all the more remarkable in that the African form referenced (the nyunga-nyunga of the Shona people) is described in exactly the same way, arising as a combination of [2-2-2] and [3-3] cycles. Again a rotated form [2-2-1-1] from South America (Colombia) merits mention over the Western trope. This sits uneasily alongside casual mentions of certain rhythms as “one of the most popular timelines used in” classical music [2-2-1-1-2] or rap music [4-3-2-3-4] without reference to examples of either, let alone any kind of statistical survey (204).

[15] That naïveté towards core music theory is also occasionally evident in the categorical organization of the book. For instance, Toussaint defines as “odd rhythms” those with a non-even-numbered-pulse-timeline (that is, “odd” in the mathematical sense). In so doing, he makes no distinction between a regular compound-meter (an Irish jig with timeline [2-1-2-1-3]), and the mixed-beat, complex meters with prime-number pulse timelines as used by the Dave Brubecks of this world (240). The absence of meter is problematic elsewhere. For instance, Toussaint returns several times to the relationship between onset positions which are diametrically opposite on the circle. This may be a meaningful parallel in binary meters as they can readily be thought of in two halves such that the opposite onsets have a comparable metrical identity, however, the same cannot be said in the context of 3-based meters. Perhaps if meter had been more substantially included, these kind of oddities (used in the pejorative sense) would have been avoided.

[16] These relatively minor criticisms and caveats aside, Toussaint’s book stands as a very fine and important work of scholarship. The Geometry of Musical Rhythm is sure to provide an intensely useful contribution to several fields if approached with sensitivity to the book’s genesis and nature, particularly to the limitations as well as the potential uses of the geometric approach. It will be of interest to ethnomusicologists and historians to engage with Toussaint’s speculation about the migration of rhythms based on internal structural properties, to music psychologists to test the extent to which the different relations are perceptually meaningful, and to music theorists and composers to further unpack the potential of properties set out here. It is also to be recommended as a general introduction, particularly for undergraduate reading-lists accompanying music theory modules (assuming that dedicated courses on musical rhythm are still too rare to merit mention). As for the future of the field, the next collection of related content will be the proceedings of the conference on “Cross-Disciplinary and Multi-Cultural Perspectives” of musical rhythm which the author is hosting at his institutional base in Abu Dhabi during March 2013.

Mark Gotham

Newton Trust Scholar

Faculty of Music, University of Cambridge

11 West Road, Cambridge CB3 9DP, UK

mrhgotham@gmail.com

Works Cited

Babbitt, Milton. 1962. “Twelve-Tone Rhythmic Structure and the Electronic Medium.” Perspectives of New Music 1, no. 1: 49–79.

Berry,Wallace. 1976. Structural Functions in Music. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Clough, John and Jack Douthett. 1991. “Maximally Even Sets.” Journal of Music Theory 35, nos. 1 and 2: 93–173.

Cohn, Richard. 1992. “Transpositional Combination of Beat-Class Sets in Steve Reich’s Phase-Shifting Music.” Perspectives of New Music 30, no. 2: 146–77.

Cooper, Grosvenor and Leonard Meyer. 1960. The Rhythmic Structure of Music. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Dunsby, Jonathan. 1994. “Criteria of Correctness in Music Theory and Analysis,” in Theory, Analysis and Meaning in Music, ed. Anthony Pople (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press): 77–85.

Handel, Steven. 2006. Perceptual Coherence: Hearing and Seeing. New York: Oxford University Press.

Hasty, Christopher. 1997. Meter as Rhythm. New York: Oxford University Press.

Lerdahl, Fred and Ray Jackendoff. 1983. A Generative Theory of Tonal Music. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Lewin, David. 1984. “On Formal Intervals between Time-Spans.” Music Perception: An Interdisciplinary Journal 1, no. 4: 414–23.

—————. 1987. Generalized Musical Intervals and Transformations. New Haven: Yale University Press.

London, Justin. 2004. Hearing in Time: Psychological Aspects of Musical Meter. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Mauch, Matthias and Simon Dixon. 2012. “A Corpus-Based Study of Rhythm Patterns,” in Proceedings of the 13th International Society for Music Information Retrieval Conference, edited by Fabien Gouyon, Perfecto Herrera, Luis Gustavo Martins, and Meinard Müller (Porto, Portugal: FEUP Ediçoes): 163–68.

Pearsall, Edward. 1997. “Interpreting Music Durationally: A Set-Theory Approach to Rhythm.” Perspectives of New Music 35, no. 1: 205–30.

Polansky, Larry. 1996. “Morphological Metrics.” Journal of New Music Research 25, no. 4: 289–368.

Pressing, Jeff. 1983. “Cognitive Isomorphisms between Pitch and Rhythm in World Musics: West Africa, the Balkans and Western Tonality.” Studies in Music 17: 38–61.

Roeder, John. 2003. “Beat-Class Modulation in Steve Reich’s Music.” Music Theory Spectrum 25, no. 2: 275–304.

Yeston, Maury. 1976. The Stratification of Musical Rhythm. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Footnotes

1. Cooper and Meyer 1960 is frequently cited as the seminal work. Prominent music-theoretic concerns during this time have included the study of rhythm in relation to meter (such as Hasty 1997) and the nature of rhythmic and metrical hierarchies (Yeston 1976, Lerdahl and Jackendoff 1983). At the same time, questions of temporality have featured prominently in the fast emerging fields of cognitive science and artificial intelligence, taking on questions of beat induction, and spearheading the search for a good model of rhythmic similarity.

Return to text

2. That list at the end of the book’s opening “prolegomenon” includes Kofi Agawu, Jeff Pressing, Simha Arom, Richard Cohn, Jack Douthett, and Dmitri Tymoczko among other scholars and some practitioners.

Return to text

3. Or see Lewin (1984) for a dedicated article on the temporal aspects of the theory.

Return to text

4. Both ‘right-angles’ and ‘syncopation’ are explained, however “maximal-area” is not and “anacrusis” is used to refer to any timeline without an onset at the start of the cycle (Figure 14.9, 81).

Return to text

5. “When a rhythm is judged as ‘good’ in this book, the word is intended to denote that it is effective as a timeline, as judged by cultural traditions and the test of time.” (28).

Return to text

6. See London (2004 second edition 2012) for a substantial engagement with rhythm, meter and temporality which counterbalances Toussaint’s work in this respect.

Return to text

7. Reading from left to right diagrams, this would entail moving the pair of pulse onsets from positions 7 and 8 to positions 6 and 7 (one step for two onsets) or moving the onset at pulse position 8 to position 6 (one onset by two steps).

Return to text

8. The example comes from Steve Reich’s Drumming. As Reich’s score does not commit to either 3/2 or 6/4 as the host meter, both are represented in the new figure. In both cases, the rhythm of the upper line reproduces that of Toussaint’s left circle, and the lower line reproduces the variant.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2013 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Carmel Raz, Editorial Assistant

Number of visits: