Review of Dora Hanninen, A Theory of Music Analysis: On Segmentation and Associative Organization. Eastman Studies in Music (University of Rochester Press, 2012)

Zachary Bernstein

KEYWORDS: segmentation, association, ecology, Benjamin Boretz

Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory

[1] The innovative perspective set forth in Dora Hanninen’s A Theory of Music Analysis: On Segmentation and Associative Organization can be glimpsed in its very title. The title proper states the scope of the project at hand: this theory is not a theory of any particular technique, composer, or body of music, but of the practice of analysis—which here seems to encompass any committed, particularized thinking about any piece of music—construed broadly. This immediately evokes one of the most conspicuous of the book’s virtues: in order to accommodate the theory’s generality, the specific analytical tools proposed are almost infinitely flexible. The subtitle, “On Segmentation and Associative Organization,” states implicitly what the book will soon make explicit in great detail, that the act of forming and relating segments is basic to analysis in this most general sense, independent of any particular repertoire, analytical technique, or governing theory. The title further suggests a motivation for the book: the process of forming and relating segments, despite the fact that it is basic to music analysis, is complex, and worth addressing directly. The result is a challenging but rewarding reimagination of analytical practice with insights and implications for almost every music analyst. A brief analytical demonstration will present some of the issues involved.

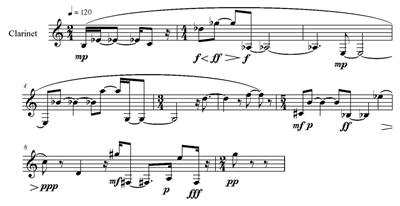

Example 1. Milton Babbitt’s Composition for Four Instruments, measures 1–9. Score in C. Accidentals affect only those notes which they immediately precede

(click to enlarge)

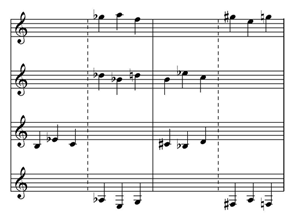

Example 2. Trichordal array for the first two aggregates of Composition for Four Instruments. Dotted lines reflect partitioning, solid lines reflect aggregate boundaries

(click to enlarge)

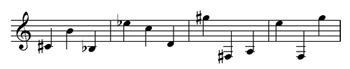

Example 3. Segmentation of the second aggregate of Composition for Four Instruments into temporally discrete (013) trichords

(click to enlarge)

Example 4. Segmentation of the second aggregate of Composition for Four Instruments into dynamically discrete (027) trichords

(click to enlarge)

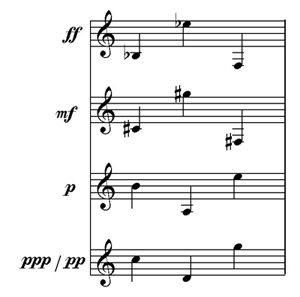

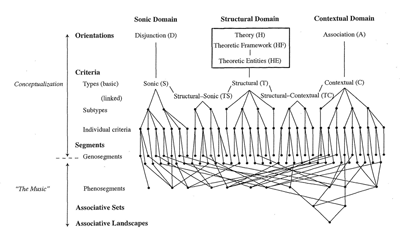

Example 5. Hanninen’s “Schematic representation of the general theory of music analysis” (Example 1-1, page 6)

(click to enlarge)

[2] Example 1 presents 24 notes. It also presents the opening of a piece of music called Composition for Four Instruments, by Milton Babbitt.(1) Surely, an understanding of those 24 notes as part of the larger whole is dependent, at the very least, on understanding them as more than just 24 isolated events, but as members of various groups that relate to each other in various ways and that themselves, eventually, compound into even larger groups. But an attempt at isolating the segments in this passage leads to numerous, conflicting possibilities for how this process might unfold.

Example 2 presents the passage’s trichordal array. This perspective highlights registrally distinct (014) trichords, their combination into hexachords, and the division of the whole passage into two aggregates. However, if we instead proceed from the presumption that silences define segment boundaries, we get a somewhat different perspective. The first trichord, as in the trichordal array analysis, is set apart from the rest of the passage by the rest that follows it. But continuing to follow the pattern of notes and rests, one would also be led to understand segment boundaries between G and D and D and F in measures 5 and 6, isolating D and F at the end of the first aggregate. The second aggregate presents a similar conflict between segmentations: rests separate the first aggregate from the second aggregate and the first pair of trichords of the second aggregate from its second pair, but two further rests appear in measure 8, isolating D in measure 8 and G in measure 9. There is an underlying relation to the trichordal array—rests follow the last-stated note of every trichord in the array—but, generally, tracking sounds and silences leads to a very different segmentation than that indicated by Example 2. From the perspective of articulation, the long slur over the first six measures divides the passage into two, the first six measures separated from the last three. This coincides precisely with the division of the passage into two aggregates, but one is left to wonder about role of the second slur, over

[3] We learn three things from this demonstration that Hanninen’s A Theory of Music Analysis is well equipped to help us understand. First, as Hanninen points out, “association can itself be a rationale for segmentation” (7). For instance, relatively little about the music puts forth dividing the second aggregate into temporally discrete trichords, as shown in Example 3, but the repeated recurrence of equivalent (013) trichords makes this a plausible option. Hanninen’s choice to address segmentation and association within the same treatise thus appears quite logical. Secondly, various possible distinct patterns of segmentation and association coexist in the same passage, and it is far from evident how or even whether one should prioritize among these patterns. Even if we do eventually want to choose among them, one wants—and Hanninen provides—analytical tools sufficiently flexible to encompass these various possibilities. Finally, the various segmentations coexist not just because they result from paying attention to different things, but because they result from paying attention to different kinds of things. Tracking patterns of rests or articulation, for instance, is a very different sort of observation than following the piece’s trichordal array. The unraveling of that array requires knowledge and experience in a way that simply recognizing the local repetitions of (013) in the second aggregate does not. Accordingly, the first step in A Theory of Music Analysis is to distinguish between the different “domains” of musical experience that affect segmentation and association. The schematic in which Hanninen presents these domains and the interrelationships between them that will form her theory is presented in Example 5.

[4] As can be seen in the schematic, Hanninen’s theory presents three domains—“sonic,” “contextual,” and “structural”—each coupled with an “orientation,” and a series of five “levels” that proceed, successively, from “conceptualization” toward the “music.” The sonic domain, appearing on the left side of the schematic, is the first she discusses. As shown in the schematic, the sonic domain is defined by its “disjunctive” orientation. The disjunctive orientation responds to relatively large differences in some musical dimension. In Example 1, for instance, the leap between C4 and

[5] The sonic domain, in which segments are defined by disjunction, corresponds to a great deal of psychoacoustic scholarship on segmentation, and Hanninen’s discussion of it makes frequent mention of scholars in this field. However, Hanninen distances herself from the scientific approach in favor of an interpretive, “humanistic” conception of analysis.(2) Because of this, the process of choosing between various possible sonically-defined segmentations is not explained using a predictive algorithm or in reference to empirical studies, but rather is left to the interpretive preferences of the analyst. Among other consequences, this results in the position that the relative importance of any particular sonic dimension “is influenced by musical context and individual judgment” (260).

[6] Context also determines the second, “contextual” domain of Hanninen’s theory. As can be seen on the right side of the schematic, the contextual domain is defined by its “associative” orientation. Simply, this domain encompasses situations in which segments are related because of one or more shared features. The possible shared features that can create associations are left completely open, encompassing all musical dimensions. Further, as noted above, association not only relates segments but can also define them. Nonetheless, most perceived segments are also defined by sonic criteria, and thus the sonic and contextual domains, though addressing opposite mental processes, often work in concert.

[7] Central in Hanninen’s schematic, but considerably less central in her theory than the contextual domain, is the “structural” domain. The structural domain concerns “theories of musical structure” invoked in the process of analysis that define “theoretical entities,” and thus segmentation, within their own “framework.” Hanninen describes Schenkerian theory and twelve-tone theory as paradigmatic examples of structural theories that suggest particular segmentations, but her use of the domain is surprisingly flexible, seemingly encompassing any preexisting framework affecting segmentation that an analyst might bring to a piece. Among the more curious criteria for segmentation or association described as stemming from the structural domain include the chorale melody “Es ist genug” in Berg’s Violin Concerto (211), canonic patterns in Nancarrow’s Study no. 37 (291–308), and Robert Morris’s compositional designs in his Nine Piano Pieces (360–400). These make for a group of criteria probably not commonly understood as results of “theories of musical structure,” but they are united by their common origin: each can be considered as conceptually prior to, or at least distinct from, the piece under examination. This origin distinguishes the structural domain from the sonic and contextual domains, which are entirely defined by the piece at hand. The structural domain is also, uniquely, expendable: not every piece suggests the presence of a governing theory, and segmentation and association in these pieces can be analyzed entirely using the contextual and sonic domains.

[8] Continuing down the schematic, we see that each of the various domains define “types” of criteria for segmentation. At this point, the precise number of lines and nodes in the schematic becomes metaphorical: there are an infinite number of possible individual criteria in each domain, limited only by an analyst’s interests and needs. Individual criteria each define “genosegments.” A genosegment is a segment defined by precisely one criterion, whether or not a listener is inclined to perceive it as a discrete segment. A “phenosegment,” on the other hand, is a “readily perceived” segment of music. If a segment is indeed readily perceived, this perception is surely fostered by at least one criterion distinguishing it from its surroundings, but most phenosegments are in fact defined by multiple, various criteria; this explains the tangle of lines connecting genosegments and phenosegments in the schematic. The terms genosegments and phenosegments, adapted from the genetic concepts of genotypes and phenotypes, constitute the first of many metaphors Hanninen draws from the biological sciences, of which more below.

[9] After the introductory overview of Chapter 1 and the preliminaries about “Orientations, Criteria, Segments” of Chapter 2, Chapter 3—much the longest of the opening theoretical chapters—addresses the heart of her analytical method: “Associative Sets and Associative Organization.” As the title of this chapter suggests, the focus here is squarely upon the contextual domain. “The contextual subschematic,” she writes, “is the theoretic and analytic focus of the book” (416). Chapter 3 introduces the concept of the “associative set,” a set of segments bound by one or more shared criteria. (There is room for confusion here: an associative set is a set of segments, not a set of notes or abstracted notes, as in a pitch-class set.) The ensuing extensive discussion encompasses the ways in which human cognition constructs relationships within and between associative sets, along with a number of creative ways to visually represent various aspects of associative organization. The most important of these are the “associative landscapes,” which depict the arrangement of associative sets over the course of a piece.

[10] Excepting a final chapter on possible extensions of the theory, the remainder of the book is analytical. A chapter each is devoted to the first movement of Beethoven’s Piano Sonata op. 2, no. 2, Debussy’s Harmonie du soir, Nancarrow’s Study No. 37, Riley’s In C, Feldman’s Palais de Mari, and Morris’s Nine Piano Pieces. In each of the analyses, the goal is the construction and examination of models of associative organization, with careful attention to the interaction between associative organization and the piece’s style and compositional techniques. Though the variety of pieces discussed means that each analysis is distinct, the analysis of In C represents a particularly extended application of the theory. Given the indeterminate score of In C, Hanninen first analyzes the associative organization of the piece’s fifty-three repeating figures themselves, before proceeding to discuss the ways several different performances effect distinct interpretations of that organization by emphasizing, obscuring, or creating associative links between various aspects of the piece. In this, we see that associative organization is not simply a fact of a piece’s score, but the result of an actual musical experience; a creation of performers and listeners as well as composers. Though Riley’s composition provides an extreme example, the principle holds broadly.

[11] As the list of analytical chapters suggests, the book’s examples are drawn primarily from twentieth-century music. Hanninen gives two reasons for this, correctly noting twentieth-century music’s exceptional diversity, including diversity of associative organization, and that it is generally less well understood than earlier music. Accordingly, one of the stated goals is to propose a “general theory of musical form that goes beyond named forms

[12] One lament I have about the book regards the quantity and quality of material buried in the endnotes. Often, a name or topic from the body of the text will receive an endnote with not only a citation, but also a quotation from the original source that sheds new light on Hanninen’s project. There are two subjects in particular that, though mentioned in the body of the text, receive new importance in the endnotes.

[13] The first of these subjects is the central set of metaphors of the book, those drawn from the biological and ecological sciences and from philosophies of those sciences. We have already seen this in the terms “genosegment” and “phenosegment,” and several other terms similarly carry biological or ecological resonances, but the importance of this metaphor goes far beyond the terminological. The whole apparatus of associative landscapes—the preeminent analytical tool of the book—is inspired by the field of landscape ecology, and the theoretical discussion of associative landscapes includes numerous citations of ecologists. An extensive metaphor is established in which an associative landscape with its associative sets and their segments is compared to an ecological landscape populated with species and organisms.

[14] There are two important things worth noting about this metaphor. The first is historical. Biological metaphors—particularly those stemming from Goethe—have a venerable history within music scholarship. Hanninen co-opts this paradigm for radically new ends, advancing it into the present by citing numerous contemporary scientists and developing the metaphor with a great deal more specificity than seen in familiar notions such as “organic continuity.” Secondly, the vision of a piece as a landscape presents a welcome alternative to more commonplace notions of form, such as those driven by teleology or expressive narrative. One is invited into the landscape simply to admire the interactions of its populations, the “intermingling of diverse musical materials” (359). Though Hanninen’s models are sensitive to the passing of time, slavish attention to temporal linearity is not required. This perspective resonates with the book’s cover art, a topographical map of Kings Canyon National Park high country, in the Sierra Nevada. It is possible to use the map for directed travel, say down the John Muir Trail, the grand traverse of the High Sierra, which winds through the map’s center. Or, one could use the map simply to look around and recognize notable features in the topography. Both are acceptable uses of a topographical map.(3)

[15] The second subject that receives new importance in the endnotes concerns Hanninen’s primary meta-theoretical influences, which include David Lewin, Joseph Dubiel, and particularly Benjamin Boretz, as well as others affiliated with them such as Robert Morris and Marion Guck. That is, this book fits quite well within the “radical relativist” meta-theory that developed among students of Milton Babbitt in the late ‘60s and afterwards.(4) A core insight of this perspective is that analysis is not explanatory, but

ontological. In Hanninen’s words, music must be “constitute[d]” from “sounding events and analytical interpretations” (5). Music’s existence, that is, is a function of a listener’s cognition. As Boretz writes in

Meta-Variations, “The very being of music is created by cognitive attributions made by individual perceiving or conceiving listeners

[16] The radical relativist position challenges most traditional justifications for musical theorizing, for it becomes more or less impossible to generalize about music when music is going to be—literally, in the ontological sense, to be—different depending upon any given listener’s particular cognitive input. Hanninen’s Theory of Music Analysis, then, is not a theory in nearly any of the usual senses of the term. It is not explanatory, predictive, normative, or evaluative. While one might use it for interpretation, it is not, of itself, interpretive.

[17] Hanninen addresses this issue in the opening pages of A Theory of Music Analysis. She describes her theory not as guiding interpretation, but as an “interpretive tool,” as a “lens that increases the grain of resolution of the analyst’s own interests and choices” (4). By creating a situation, through a combination of close investigation and imaginative representation, in which analysts must carefully reexamine their motivations for particular segmentations and associations, the theory’s effect is not instructive as much as it is consciousness-raising. Her theory thus fulfills Boretz’s promise, cited on the first page of A Theory of Music Analysis, that the human “faculty for imagining and abstracting” can be “mobilized” toward “self-directed sensitization and strength in the service not only of creating our own experience, but of making it more real, making it more substantial, and more particular and specific for ourselves” (Boretz 1992, 339).

[18] The increased “sensitization” that Hanninen’s theory inspires, and her repeated reminders of the cognitive status of musical ontology, results in renewed awareness of the degree to which segmentations and associations are chosen by the listener. Having recognized this, one is inspired to make more choices—choices perhaps not fully entertained on a first listening—and thus to expand, complicate, and enrich one’s musical experience. This, in turn, brings us to a final Boretz quotation.

Creative interaction with one’s own musical experience is a radically different kind of theorizing, trading in authoritative prescription for imaginative re-creation, recognizing the musical in music by leaving it normatively uninvaded. (2000–2001, 67)

That is, by creating a framework in which the task of forming associative patterns becomes affirmatively creative, Dora Hanninen inspires us to find the musical in music. The result, despite all the rigor of her work, is the replacement of “authoritative prescription”—the authority of theories, norms, habits, even unreflective first impressions—with liberation.

Zachary Bernstein

City University of New York, Graduate Center

365 Fifth Avenue

New York, NY 10016

zachbernst@aol.com

Works Cited

Boretz, Benjamin. 1977. “What Lingers on (, When the Song is Ended).” Perspectives of New Music 16, no. 1: 102–9.

—————. 1992. “Experiences with No Names.” Perspectives of New Music 30, no. 1: 272–83.

—————. (1969) 1995. Meta-Variations: Studies in the Foundation of Musical Thought. Red Hook, N.Y.: Open Space Publications.

—————. 2000–2001. “Thinking about Theory, Theories, and the ‘Musical’ in Music.” Intégral 14–15: 67.

Gleason, Scott. 2005. “(Re) composition at the Edges of ‘Radical Relativism.’” Perspectives of New Music 43, no. 2: 1–44, no. 1: 192–215.

Hanninen, Dora. 2001. “Orientations, Criteria, Segments: A General Theory of Segmentation for Music Analysis.” Journal of Music Theory 45, no. 2: 345–433.

—————. 2006. “‘What is about, is also of, also is’: Words, Musical Organization, and Boretz’s Language, as a Music, ‘Thesis.’” Perspectives of New Music 44, no. 2: 14–64.

—————. 2009. “Species Concepts in Biology and Perspectives on Association in Music Analysis.” Perspectives of New Music 47, no. 1: 5–68.

Mead, Andrew. 1994. An Introduction to the Music of Milton Babbitt. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Footnotes

1. For an extensive discussion of Composition for Four Instruments, see Mead 1994, 55–76. Brief comments on several of Babbitt’s compositions appear throughout Hanninen’s book, but the analysis here is my own.

Return to text

2. “Studies in music cognition and computer modeling can reveal important constraints on the interpretive process, but proceed by tenets (including prediction) and pursue goals that are fundamentally different from those of music analysis as a humanistic endeavor” (236).

Return to text

3. Much more extensive discussion of biology and its relevance for musical studies can be found in Hanninen 2009.

Return to text

4. The term “radical relativism” stems from Boretz 1977; see Gleason 2005 for further discussion of this aspect of Boretz’s thought. Hanninen is forthright about her indebtedness to Boretz and other Princetonian meta-theorists in many places throughout her work. Interesting discussions and exemplifications of this aspect of her thinking can be found in Hanninen 2001 and Hanninen 2006.

Return to text

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2013 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Brent Yorgason, Managing Editor

Number of visits: