The Parameter Complex in the Music of Sofia Gubaidulina *

Philip A. Ewell

KEYWORDS: expression parameter, Gubaidulina, Kholopova, Parameter Complex, Russian music, Russian music theory

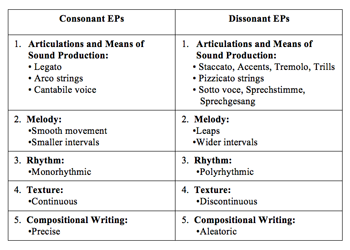

ABSTRACT: Although the music of Sofia Gubaidulina is well known, it has received little analytical attention. Approximately twenty-five years ago her friend and colleague Valentina Kholopova worked out a system for analyzing Gubaidulina’s music. Kholopova shows that the composer usually groups together five so-called expression parameters (EP): articulation and methods of sound production, melody, rhythm, texture, and compositional writing. Moreover, each EP has either a consonant or a dissonant function; rarely does Gubaidulina mix the two functions. These ten parameters—five EPs functioning as either dissonant or consonant expressions—form what Kholopova calls the Parameter Complex in Gubaidulina’s music. In this article I examine these topics, using Gubaidulina’s Concordanza and Ten Preludes for Solo Cello as exemplars.

Copyright © 2013 Society for Music Theory

[1] Though her compositions are well known and widely performed, little analytical work has been done on the music of Sofia Gubaidulina (b. 1931). Roughly twenty-five years ago her friend and colleague Valentina Kholopova devised a system for analyzing Gubaidulina’s music. The system is briefly mentioned in Kholopova’s monograph on the composer (1996) and more thoroughly laid out in Kholopova’s “Parametr ekspressii v muzykal’nom iazyke Sofii Gubaĭdulinoĭ” (The Expression Parameter in the Music of Sofia Gubaidulina) (1999).(1) Kholopova has shown that Gubaidulina usually groups together five types of expression parameters (hereafter EP: in Russian, parametr ekspressii): articulation and methods of sound production, melody, rhythm, texture, and compositional writing.(2) Further, each of these parameters can function in one of two ways: as a consonant EP or a dissonant EP. An example of a consonant articulation EP would be a legato marking, while a contrasting dissonant articulation EP would be a staccato marking.(3) Rarely does Gubaidulina mix the consonant and dissonant functions. These ten parameters—five EPs functioning as either dissonant or consonant expressions—form what Kholopova calls the Parameter Complex (kompleks parametrov) in Gubaidulina’s music.(4) I begin my article, which falls squarely under the rubric of “analysis for performance,” by further discussing Kholopova’s analytical ideas. Then I consider Kholopova’s analysis of Gubaidulina’s Concordanza, after which I present my own analysis of two of Gubaidulina’s Ten Preludes for Solo Cello. Finally, I demonstrate the interpretive efficacy of the Parameter Complex by performing part of Gubaidulina’s Seventh Prelude for Unaccompanied Cello.

The Expression Parameter

[2] Kholopova begins by defining the EP:

The “Expression Parameter” is so named because its elements are very immediate in emphasis and directly convey a musical-emotional expression. Despite its name, it belongs not to the category of musical character but, rather, to that of musical composition, standing in an array of such concepts as harmony, rhythm, and texture. (1999, 153–54)

She continues:

At the basis of the EP lie those elements of music that are not yet recognized as structural in the history of composition: the devices of articulation and the methods of sound production, which in the past have pertained to the performer and not the composer. Several elements of melody, rhythm, and texture—organized in a specific fashion—are associated with these devices of articulation. That it has a clear functional organization, similar to how classical harmony is organized by “T, S, D” functions, serves as an indicator and guarantee of the EP’s existence. (1999, 154)

[3] Kholopova immediately describes the EP as a structural component of composition, thus elevating the status of elements that have historically not been considered structural in music. She also suggests in this quotation that the first EP, “devices of articulation and the methods of sound production,” relates to the next three EPs, “melody,” “rhythm,” and “texture,” in various ways. For example, an articulative device such as a ricochet bowing may be associated with a certain rhythmic figure, since such thrown bowings often involve quick quintuplets or sextuplets. Kholopova raises the importance of the performer in the musical process since the performer must take ownership of certain structural elements of the composition and, as such, is an integral part of the composition’s success.(5) Her use of the term “function” (funktsiia) is important in that she is equating her EPs with one of the most important aspects of musical structure, namely, functionality. In other words, she is building a case for viewing the EP on equal terms with harmony, melody, rhythm, and texture.

Concordanza

Example 1. Parameter Complex for Gubaidulina’s Concordanza (1971), by Kholopova (1999, 154)

(click to enlarge)

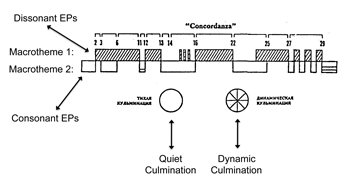

[4] In her analysis of Gubaidulina’s Concordanza (1971) for chamber ensemble, Kholopova provides a Parameter Complex (see Example 1) that features the five consonant and five dissonant EPs for the piece. The EP groupings help the performer make sense of the work. Kholopova claims that there are two layers (sloĭ) in Concordanza, one that corresponds directly to “consonance,” the piece’s namesake, and the other to “dissonance”; these layers are the consonant and dissonant EPs (1999, 155).

[5] By simply identifying the EPs, however, Kholopova has said nothing about the large-scale structure of Concordanza. To grapple with such broader ideas she draws on the work of the Soviet musicologist Viktor Bobrovskiĭ and his notion of large-scale themes in twentieth-century music. He called these themes, variously, “dramaturgical themes,” “superthemes,” or “macrothemes” (cited in Kholopova 2011, 123).(6) Bobrovskiĭ’s macrotheme—which can span an entire movement or an entire composition, though with possible breaks—generates the formal structure of the piece. Though such a theme may have more traditional melodic and rhythmic elements, it more likely is articulative or textural in nature. Thus it is possible to think of the EPs as part of the macrothematic structure. By tracing the consonant and dissonant functions of the parameter complex and by linking each to a macrotheme, Kholopova is able to map a piece’s large-scale form via the interaction of the consonant and dissonant macrothemes.

[6] Below is an extended passage in which she defines the concept:

If we analyze the form of Gubaidulina’s Concordanza traditionally, in terms of themes, we find a through composition “a, b, c, d, e, f, g . . . ,” with a small reprise of “a” at the end. Such a composition would seem formless and weakly organized. However, when we examine the piece in terms of the EPs and their functions, we discover a wonderful unity of form with just two contrasting layers, which result in “macrothemes.” A macrotheme, . . . in contrast to the normal classical theme, stretches from the beginning to the end of the composition, albeit with possible breaks. Thus, instead of a formless multithematic structure, a functionally organized bithematic structure—corresponding to the consonant-dissonant-EP functional pair—is revealed. During Concordanza, two macrothemes variously interact with each other, arriving at quiet and dynamic culminations and, ultimately, the dissonant theme impacts the consonant theme, in the last section with the thematic reprise of “a.” (1999, 155)

Example 2. Kholopova’s EP Analysis of Gubaidulina’s Concordanza (entire piece, rehearsal numbers on top, with my English annotations) (1999, 155)

(click to enlarge)

[7] Example 2 shows Kholopova’s macrothematic graph of Concordanza.(7) If you follow the graph in Example 2 as you listen to the piece you can see how it works with the music. For instance, the opening is made up of consonant EPs (part of Macrotheme 2), played by legato woodwinds, until the pizzicato bass enters at rehearsal 2, which is shown as a dissonant EP (part of Macrotheme 1) on the graph. The graph also shows how the two macrothemes can happen concurrently (e.g., from rehearsals 3 to 6) or separately (e.g., from the beginning to rehearsal 2 with the consonant macrotheme or from rehearsals 2 to 3 with the dissonant macrotheme). Furthermore, at rehearsal 14 there is a “quiet culmination” (a culmination of the consonant EPs, played by bowed strings, basses with stopped strings and violins with harmonics), and at rehearsal 22 there is a “dynamic culmination” (a culmination of the dissonant EPs, played by the whole chamber orchestra with various dissonant EPs). During the quiet culmination there are pp cymbal strikes, which are represented on the graph as three slivers of dissonant EPs shown between rehearsals 14 and 16. Usually, one macrotheme moves abruptly to the other, as at rehearsals 2, 11, 12, 13, 16, 22, 27, and 29. Sometimes, however, there is overlap between the two macrothemes, for instance between rehearsals 22 and 25 when the music moves more gradually from one macrotheme to the other. Kholopova also shows how the dissonant EPs invade the space of the consonant macrotheme between rehearsal numbers 11 and 12 and after rehearsal 29. This ending at rehearsal 29, which she calls a “reprise–coda,” represents a “collision” (stolknovenie) between consonance and dissonance (2011, 125).

[8] From a performance standpoint, Kholopova’s graph is important for several reasons. The square brackets on top of the graph link significant moments in the bithematic structure together. Because these brackets always conjoin with rehearsal numbers, a conductor will always know where the significant moments are; for example, knowing that the music between rehearsals 16 and 20 is a single dissonant span lets performers know not to make any large breaks in this section. Further, the consonant/dissonant divide suggests to performers how to highlight contrasting elements that might otherwise be harder to convey. The quiet and dynamic culminations guide performers to emphasize the two most extreme moments of Concordanza. Finally, by looking at the graph one can better gauge the balance between dissonance and consonance on the whole. In other words, the graph allows performers to more easily envisage the composition as a complete unit and then make appropriate decisions in terms of which parts to bring out and which to perhaps deemphasize.

[9] Kholopova claims that, with Concordanza, the EP became Gubaidulina’s favorite method for composing. Further, Kholopova says:

The functional EP system itself gets developed in Gubaidulina’s music. In particular, the “consonant expression” splits into “perfect” and “imperfect” consonances, while the “dissonant expression” splits into “perfect” and “imperfect” dissonances. In separate voices it’s possible to have a gradual modulation from “consonance” to “dissonance,” and vice versa. (1999, 156)

With this, a “modulation” from one extreme to the other is possible:

Perf. Cons. EP → Imp. Cons. EP → Imp. Diss. EP → Perf. Diss. EP

[10] Kholopova concludes that this system offers a structural backdrop for Gubaidulina’s music, and that the EP and the Parameter Complex show a new dimension in music. Finally, she claims that this system could be applied to music of other twentieth-century composers for whom timbre, texture, and color were paramount.

[11] In his biography of Gubaidulina, Michael Kurtz observes that Concordanza represented a watershed moment for the composer. The compositional techniques were new and she began to invest them with spiritual significance. For example, Kurtz discusses the evolving nature of her compositional output by relating her spirituality to the “staccato” and “legato” EPs identified by Kholopova:

Concordanza stands at the beginning of a new chapter in Gubaidulina’s creative work, regarding both technique . . . and her general religious and spiritual attitude toward her work as a composer. In later years Gubaidulina often said that art has a religious function, that in the “staccato” of life it must restore the “legato.” Art is the re-ligio (connection) to God in our fragmented, quotidian life. The religious intensity and drama that had found direct expression through the existential situation in her earlier cantatas now began to shape the music itself, which in all its dimensions suggests religious feeling and religious intention. Titles like Concordanza and notations such as staccato and legato took on connotations suggesting the religious dimension. (2007, 95–96)

Ten Preludes for Solo Cello

[12] The Ten Preludes for Solo Cello came right on the heels of Concordanza. Originally written as Ten Etudes in 1974 for the cellist Grigoriĭ Pekker of the Novosibirsk Conservatory, each piece explores different cellistic EPs. Not a fan of contemporary music, Pekker was surprised by Gubaidulina’s etudes and shelved them. Later, the cellist Vladimir Tonkha of the Kazan Conservatory premiered the etudes in 1977, and renamed them “preludes”; the ten vignettes have existed as such ever since.

[13] Kholopova writes, “Gubaidulina’s Ten Preludes are built on different types of musical expressions, which enrich their compositional technique” (2011, 137; her italics). Gubaidulina herself says, “These miniatures, which evoke polar opposites in the sphere of sound production on a string instrument, are little scenes in which the heroes are: (1) certain aspects of string instrumentation, (2) methods of sound production, and (3) various bowings. . . . In almost all of the pieces the opposites interact in pairs” (cited in Kholopova 2011, 137). Here are the titles of the preludes:

- Staccato—Legato

- Legato—Staccato

- Con sordino—Senza sordino

- Ricochet

- Sul ponticello, ordinario, sul tasto

- Flagioletti

- Al taco—Da punta d’arco

- Arco—Pizzicato

- Pizzicato—Arco

- Senza arco, senza pizzicato

Preludes 1, 2, 3, 7, 8, and 9 feature paired EPs. Moreover, Preludes 1 and 2 and Preludes 8 and 9 are repeated pairs in reverse form. Preludes 4 and 6 are single-EP preludes, while Prelude 5 is a tripartite-EP prelude. Finally, Prelude 10 features no right hand at all, only the left hand making sounds on the fingerboard, and can thus be thought of as a single-EP prelude. As Kurtz suggests, after Concordanza Gubaidulina did indeed start to think of “staccato” and “legato” in broader terms—as more than mere articulations. One might even think of these two terms as metonyms for “dissonant EP” and “consonant EP,” respectively.

Example 3. Gubaidulina, Prelude No. 1 for Solo Cello (1974), measures 1–41

(click to enlarge)

[14] Example 3 shows the first 41 measures of Prelude 1, “Staccato—Legato,” whose title indicates the main EP of the movement. What the performer must do in approaching this piece is think not only of the titular EP pairing, but also of the piece’s entire Parameter Complex. Other possible EPs for Prelude 1 include dynamics, fermatas, meters, contour, the numbers of notes in groupings, grouping and spacing of rests, conjunct or disjunct motion, and what string to play.

[15] One must group all EPs into consonant and dissonant functions to pull off a convincing performance. The opening staccato EP lasts for 35 measures. The first clear motion to the legato EP is in measure 36. Notably, the dynamic at that point is an unadulterated f, whereas leading up to that point the dynamics were softer. Thus, the f dynamic would be included in the consonant EP column with “legato,” while the p dynamic would be part of the dissonant “staccato” column. In this fashion one can create a Parameter Complex for the prelude. As these observations demonstrate, context is paramount in the Parameter Complex. It may seem counterintuitive to call f “consonant” and p “dissonant” in any analysis but, with respect to contrasting EPs, this is clearly the case in Prelude 1. Significantly, Kholopova says nothing about any EPs that are consistent throughout all of Gubaidulina’s output, though one can surmise that “legato” is always consonant and “staccato” is always dissonant.

[16] In his article, “The Importance of Bodily Gesture in Sofia Gubaidulina’s Music for Low Strings,” Michael Berry says:

Sofia Gubaidulina is one of many composers whose music features an increased attention to the body. . . . In some instances, I would argue that practical bodily gestures—those movements of the body that are concerned with producing sound from one’s instrument—are actually more important to the work than the resulting sounds. (Berry 2009, [2])

Berry goes on to talk about the difference between “practical” and “expressive” gestures in performing Gubaidulina’s music for low strings. Below, I argue that this distinction can be part of the Parameter Complex.

Example 4. Parameter Complex, Gubaidulina’s Prelude No. 7 for Solo Cello (1974)

(click to enlarge)

Example 5. Gubaidulina, Prelude No. 7 for Solo Cello (1974), measures 1–35

(click to enlarge)

Video Example 6. Prelude 7 Demonstration

(click to watch)

[17] In Example 4 I created a Parameter Complex for Prelude 7, whose first thirty-five measures are shown in Example 5. I have not included “rhythm” or “compositional writing” in the complex since there is but one rhythm in one meter in a non-aleatoric setting for the prelude. In deciphering the prelude’s title, “Al taco—da punta d’arco” (From the frog to the tip of the bow), one must determine whether the repeated down bows right at the beginning are consonant or dissonant. I have chosen the latter for three reasons: the piece ends on all up bows, and Gubaidulina has a penchant for ending pieces on a consonance; the opening features irregular five-note groups in a duple meter, which can be considered dissonant in this context; and there are accents on the quintuplets, which also points to a possible dissonant expression.

[18] Example 6 provides a video demonstration of measures 1–35 of Prelude 7. It should be clear from the video that by jumping back and forth from the tip to the frog of the bow, I am privileging Berry’s “expressive” gesture over any “practical” gesture (which would undoubtedly be easier to play). By playing the piece with a Parameter Complex in mind, I believe I am giving a more convincing performance, closer to the composer’s intentions, than one that strictly considers the main EP for the piece.

[19] What is more, my interpretation of the isolated down and up bows allows for the possibility of crucifixion symbolism. About her Seven Words for cello, bayan, and strings, which she dedicated to Vladimir Tonkha, Gubaidulina says:

As a specific feature of Seven Words (1982), I would point to the symbols of the cross. There are many crosses of different kinds: for example, numerous extensions and narrowings of the musical space in the cello part. . . . The crucial thing for me was the idea of the crucifixion. I like very much the idea of instrumental symbolism, when the instrument itself, its nature and individuality, hints at or implies a certain meaning. . . . I wanted to find the idea of the cross in the instruments themselves. The first thing that came to mind, obviously, was the “crucifixion” of a string. This idea is employed throughout the entire composition, from the very beginning. (Lukomsky 1998, 20)

If one envisions the strings of the cello, which are of course vertical as the cellist plays, it is easy to imagine that the leaping from frog to tip with the bow against the backdrop of the four strings resembles the crucifixion symbol or “crossing oneself” that is prominent in many branches of Christianity. Even though the preludes’ premiere predates Seven Words by seven years, it is entirely possible that Gubaidulina thought of crucifixion in Prelude 7 as the cellist leaps from frog to tip across the vertical strings and that it is proper to play the piece as I have in Example 6.

Conclusion

[20] The following quotation summarizes Kholopova’s main conclusions about the EP and the Parameter Complex:

The EP is but one of many parameters that organize contemporary music, . . . Organizing musical form along with different parameters, the EP sometimes appears at a background level of structure, as in Concordanza. . . . The rise of the EP is a sign of a continually progressing movement in the language of contemporary music. But if progress in European music was traditionally connected with harmony, then the EP, not being from the realm of harmony strictly speaking, shows the different dimensions of music. . . . The EP in European music first manifested itself as a system in the music of Anton Webern. In one fashion or another it is present, aside from the work of Gubaidulina, in the compositions of many contemporary composers, . . . which allows us to acknowledge the existence of this new musical parameter. (1999, 159–60)

Notably, she mentions that the EP got its start with the music of Webern, a composer often cited as one of the most influential pioneers in twentieth-century compositional techniques.(8) She goes to great pains to show how Gubaidulina’s music is structured, not fragmented, and—more importantly, in her opinion—unified. Kholopova has given the performer a wonderful way of organizing the many contrasting aspects of Gubaidulina’s music. A consideration of the Parameter Complex is sure to lead to much more refined performances of her works.

Philip A. Ewell

Hunter College

Department of Music

695 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10065

pewell@hunter.cuny.edu

Works Cited

Berry, Michael. 2009. “The Importance of Bodily Gesture in Sofia Gubaidulina’s Music for Low Strings.” Music Theory Online 15, no. 5.

Bobrovskiĭ, Viktor. 1970. O peremennosti funktsii muzykal'noĭ formy (On the variability of function in musical form). Moscow: Muzyka.

—————. 1978. Funktsional'nye osnovy muzykal'noĭ formy (The functional bases of musical form). Moscow: Muzyka.

Ewell, Philip. 2013. “Russian Pitch-Class Set Analysis and the Music of Anton Webern.” Gamut: Online Journal of the Music Theory Society of the Mid-Atlantic 6, no. 1.

Kholopova, Valentina. 1973. “Ob odnom printsipe khromatiki v muzyke XX veka” (On one principle of chromaticism in twentieth-century music). In Problemy muzykal’noĭ nauki (Problems of musical science), 2nd installment, 331–44. Moscow: Sovetskiĭ Kompozitor.

—————. 1996. Sofiia Gubaĭdulina. S interv’iu S. Gubaĭdulinoĭ—E. Restan’o (Sofia Gubaidulina, with an interview of Gubaidulina by E. Restagno). Moscow: Kompozitor.

—————. 1999. “Parametr ekspressii v muzykal’nom iazyke Sofii Gubaĭdulinoĭ” (The expression parameter in the music of Sofia Gubaidulina). Moscow Forum. International Conference Proceedings, vol. 25: 153–60. Moscow: Moscow Conservatory.

—————. 2011. Sofiia Gubaĭdulina: Monografiia (Sofia Gubaidulina: A monograph). 3rd edition. Moscow: Kompozitor.

Kholopova, Valentina, and Yuri Kholopov. 1984. Anton Vebern: Zhizn’ i tvorchestvo (Anton Webern: Life and work). Moscow: Kompozitor.

—————. 1999. Muzyka Veberna (The music of Webern). Moscow: Kompozitor.

Kurtz, Michael. 2007. Sofia Gubaidulina: A Biography. Translated from German by Christoph K. Lohmann. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Lukomsky, Vera, and Sofia Gubaidulina. 1998. “My Desire Is Always to Rebel, to Swim against the Stream!” Perspectives of New Music 36, no. 1: 5–41.

Footnotes

* I would like to thank Valentina Kholopova, on whose work this paper is based, for her help with this topic and for our many wonderful conversations. I would also like to thank Ellon Carpenter and Inessa Bazayev for their work in putting together “Perspectives on Twentieth-Century Russian Theory.”

Return to text

1. All translations from Russian to English are my own. I have used the transliteration system of the Library of Congress, which can be found in the Chicago Manual of Style (16th ed.), on page 568, Table 11.3.

Return to text

2. “Compositional writing” (kompozitorskiĭ tekct) simply refers to whether the music is precisely notated or aleatoric.

Return to text

3. It is hard to say how consistent the EPs and their two potential functions are in Kholopova’s system, for the simple reason that she has not applied it extensively. It seems that the five EPs are consistent while their functions are contextual: there are never more than the five parameters but whether a pizzicato articulation, for example, is consonant or dissonant depends on how it is used in the composition at hand.

Return to text

4. This term appears in neither Kholopova 1999 nor Kholopova 2011; I learned of it from my discussions with Kholopova. She wanted to give the five types of expressions, existing in two functions each, a name that would encapsulate them in their entirety, so she devised the term komplekc parametrov (parameter complex).

Return to text

5. Of course, the performer is a necessary part of any composition’s success. What Kholopova is suggesting is that the performer take on more responsibility for that success in performing Gubaidulina’s music.

Return to text

6. Bobrovskiĭ (1906–1979) worked on the functional organization of musical form, primarily, and on problems of dramaturgy in music. See Bobrovskiĭ 1970 and 1978.

Return to text

7. Here are two YouTube links that include complete recordings of Gubaidulina’s Concordanza:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MDRDkljsuRw; and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4cY73PPnQJc.

Return to text

8. Kholopova has written extensively on Webern (see Kholopova 1973 and Kholopova and Kholopov 1984 and 1999). For more on her work on Webern, see Ewell 2013.

Return to text

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MDRDkljsuRw; and https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4cY73PPnQJc.

Copyright Statement

Copyright © 2013 by the Society for Music Theory. All rights reserved.

[1] Copyrights for individual items published in Music Theory Online (MTO) are held by their authors. Items appearing in MTO may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the author(s), and advance notification of the editors of MTO.

[2] Any redistributed form of items published in MTO must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in Music Theory Online in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] on [DAY/MONTH/YEAR]. It was authored by [FULL NAME, EMAIL ADDRESS], with whose written permission it is reprinted here.

[3] Libraries may archive issues of MTO in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of MTO, who will act in accordance with the decisions of the Society for Music Theory.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.

Prepared by Michael McClimon, Senior Editorial Assistant

Number of visits:

23878